Abstract

Introduction: Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a diverse group of disorders characterized by clonal proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells, ineffective hematopoiesis, and cytopenia. These disorders can be difficult to diagnose and carry a high risk of evolution to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Prognostic risk is determined by cytogenetic and molecular features. Outcomes are dependent on pathologic, molecular, and clinical features. However, it is becoming increasingly apparent that socioeconomic and racial/ethnic differences also contribute to disparate outcomes in hematologic malignancies and MDS. Here, we analyzed in-hospital death among MDS-related hospitalizations and evaluated differences in sociodemographic characteristics, focusing on the effect of primary payer on MDS mortality.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), the largest all-payer database of hospital admissions in the United States, from January 1st, 2010 through December 31st, 2019. The study sample consisted of adult (18 years and above) hospitalizations with MDS diagnosis captured using ICD-9 and 10 codes indicative of MDS. We performed adjusted survey logistic regression analyses to assess associations between sociodemographic characteristics (exposure) and in-hospital mortality among MDS hospitalization (outcomes).

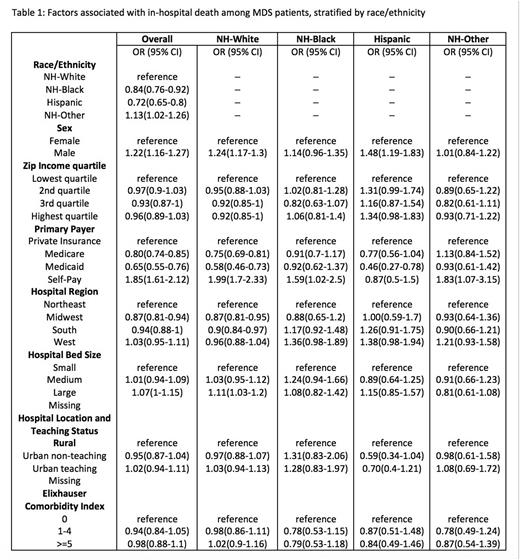

Results: Our data captured 304,050,043 hospital encounters of adult patients from 2010 to 2019, and 787,105 of those had a MDS diagnosis. Overall, patients who self-paid were more likely to have in-hospital mortality compared to those with private insurance [odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval: 1.85 (1.61-2.12)]. In contrast, patients with Medicare or Medicaid had less in-hospital mortality compared to those with private insurance [OR: 0.80 (0.75-0.85) and 0.65 (0.55-0.76) respectively). This trend was observed in NH-White, NH-Black, and NH-other patients and was most pronounced and significant in the NH-White population. Among NH-White patients, in-hospital mortality in self-paid was nearly double to their privately insured counterparts [OR 1.99 (1.70-2.33)]. Additional findings noted were relatively higher in-hospital mortality among overall males compared to female [OR 1.22 (1.16-1.27)] and higher among NH-white compared to NH-black or Hispanic (Table 1). Interestingly, the Midwest region had better outcomes than the other regions, and Medicaid patients had better outcomes than other payer groups (Table 1).

Conclusion: In-hospital mortality was higher in self-paid patients, both overall as well as in multiple racial/ethnic groups. Patients with Medicaid were relatively younger which might have resulted in better mortality outcome noted in our study. It is possible that those who are self-paid are too young to qualify for Medicare, are low-income but not enough to qualify for Medicaid, or do not qualify for public assistance due to other unmeasured variables, such as undocumented residency status. Self-paid patients may delay seeking care and have fewer interactions with the healthcare system prior to hospitalization due to associated cost and thus are sicker at time of hospitalization. Further research is needed to explore if this disparity in mortality in self-paid patients is related to access to care, treatment received including transplant status, or the disease severity and its complications.

Disclosures

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal