In this issue of Blood, Vitale et al report that treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) with targeted therapies (ie, ibrutinib, idelalisib, and venetoclax) does not change the prevalence of autoimmune cytopenia (AIC) compared with untreated patients. Moreover, targeted therapies are effective in the management of both underlying CLL and AIC.1

The relationship between AIC and CLL is well-known, autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) appearing in 5% to 10% of the patients, and autoimmune immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) in 2% to 5% of patients. AIC may be diagnosed before, at presentation, or at any point during the course of CLL. It may also be observed in either untreated or treated patients. Also, AIC tends to appear in patients with high-risk CLL (ie, unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region gene [IGHV], 17p and 11q deletion).2

It is generally accepted that treatment of CLL may trigger AIC. The relationship between treatment initiation and the development of AIHA was identified in seminal descriptions of the disease. In the 1990s, it was shown that patients treated with fludarabine as a single agent could be at higher risk of developing AIHA. This concept, however, was based on retrospective studies in highly selected, high-risk patients. Interestingly enough, anecdotal cases of patients with CLL and accompanying AIHA in which both CLL and AIHA responded to fludarabine were reported. Furthermore, in studies conducted in the 2000s, highly effective treatments combining fludarabine with other agents (ie, cyclophosphamide [FC], FC + rituximab [FCR]) were associated with a low proportion of AIHA. Taken together, these results convincingly suggest that rather than treatment it is the lack of response to it that conveys a higher risk of AIC.3

As patients with either a prior history of AIC or active AIC are usually excluded from clinical trials, the proportion of cases in which a given therapy is associated with AIC recurrence or worsening of AIC is unknown. Likewise, whether the investigated “CLL therapy” is effective as “AIC therapy” cannot be determined.

What do we know about targeted therapies (B-cell antigen receptor inhibitors [BCRi’s], BCL-2 inhibitors), and CLL-related AIC?

New-onset AIC was rarely reported in the seminal studies on ibrutinib.4 Moreover, 2 pooled analyses of the few patients who had active but controlled AIC at the time of starting therapy showed that AIC improved or resolved in 50% and 86% of the patients, respectively. BCRi’s act not only on neoplastic B lymphocytes but also on immunosurveillance and microenvironment.5,6 Of note, BCRi’s (ie, inhibitors of Bruton tyrosine kinase) are being investigated as potential therapy in a wide range of autoimmune disorders.6 Therefore, in patients receiving small molecules, CLL and AIC could be considered a single target.

Two retrospective studies addressed the prevalence of AIC in subjects with CLL-treated ibrutinib and/or idelalisib, as well as their efficacy in AIC, if present.7,8 The Mayo Clinic reported a 6% prevalence of treatment-emergent AIC in 193 patients receiving ibrutinib. Of note, ibrutinib resulted in a remarkable improvement of the AIC with 8 of 12 patients (67%) being able to discontinue AIC treatment.7 The French Innovative Leukemia Organization (FILO) group reported a response rate >90% in 25 patients treated with ibrutinib or 19 patients who received idelalisib.8 Although the impact of AIC on the outcome of patients with CLL remains controversial, these 2 studies indicate that in patients receiving BCRi’s, the appearance or a prior history of AIC does not affect survival.

The Vitale et al paper is the largest retrospective series of patients with CLL-related AIC managed with ibrutinib-based therapy (n = 572), idelalisib plus rituximab (n = 143), and venetoclax with or without rituximab (n = 100), the prevalence of AIC being 1%, 0.9%, and 7%, respectively. These results are consistent with the concept that targeted therapies are not associated with a higher risk of AIC, and that, if present, can be managed with immunosuppressive agents (eg, steroids, rituximab). Likewise, the preexistence of AIC did not negatively impact patients’ outcomes. In addition, as in prior studies, patients who developed AIC were more likely to have high-risk CLL. Of note, the association of AIC with high-risk biomarkers could explain the poor prognosis of CLL-related AIC found in some studies.

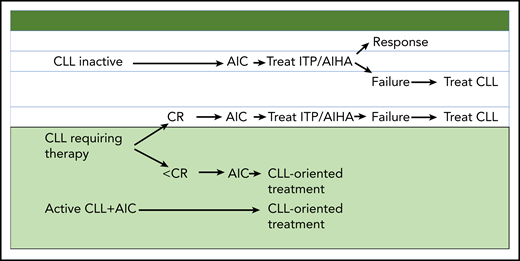

How does the current information, including the data reported by Vitale et al, translate in terms of management? When no CLL therapy is needed, AIC should be treated according to existing guidelines for AIHA and ITP. Nonresponding patients should be given CLL therapy. In CLL patients in need of therapy who do not achieve a complete response (CR) and subsequently develop AIC, and in those with concomitant active CLL and AIC, a front-line “CLL-oriented treatment” approach should be considered. A reasonable approach consists of a short course (2 to 4 weeks) of corticosteroids followed by effective CLL therapy (ie, FCR, bendamustine plus rituximab or ibrutinib), depending on the clinical situation (see figure).

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.