In this issue of Blood, Rogers and colleagues demonstrate the clinical benefit of ibrutinib for relapsed hairy cell leukemia in a phase 2 clinical trial.1

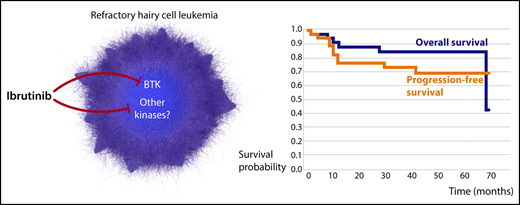

Ibrutinib provides a new therapeutic solution for patients with refractory HCL. Treatment with ibrutinib resulted in durable responses in these patients, irrespective of the status of BCR signaling. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

Ibrutinib provides a new therapeutic solution for patients with refractory HCL. Treatment with ibrutinib resulted in durable responses in these patients, irrespective of the status of BCR signaling. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

In the past 2 decades, few drugs have made as rapid and successful a journey from discovery to clinical implementation as ibrutinib. Ibrutinib is a highly potent, irreversible, orally bioavailable Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor that targets the cysteine residue at position 481 (Cys-481) and blocks binding of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), resulting in the inhibition of the phosphorylation of BTK and downstream targets, suppression of B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling and cellular proliferation, and induction of apoptosis. Since its arrival on the scene in 2007,2 ibrutinib has demonstrated profound antitumor activity in several B-cell malignancies, and has transformed clinical outcomes of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), mantle cell lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, and Waldenstrӧm’s macroglobulinemia.3-7

In this important study, Rogers and colleagues show that the clinical utility of ibrutinib can be expanded further to hairy cell leukemia (HCL). HCL is a rare B-cell malignancy characterized by 2 principal subtypes, a classic form that often features the presence of the V600E BRAF mutation and generally has a good prognosis and a variant form that exhibits limited response to standard treatment, with purine analogues, and poses a substantial therapeutic challenge.8 They conducted a phase 2 multisite, open-label, single-agent study of ibrutinib for patients with HCL relapse and those for whom standard purine analogues were not a feasible therapeutic option. A total of 37 patients, 76% with classic and 24% with variant HCL, were enrolled in the study. Although the study did not meet the prespecified overall response rate (ORR) of 50% at 32 weeks for the primary end point, remarkably, a majority of these patients, heavily pretreated for HCL, displayed durable response with a median overall survival (OS) of 69 months (see figure). Importantly, HCL subtype and other clinical features did not influence treatment response, and increasing age was the only factor that exerted a negative impact on clinical outcome. Ibrutinib was reasonably well tolerated, and observed toxicities were comparable to those reported in other B-cell malignancies.

Rogers and colleagues discovered that, similar to CLL, deeper responses occurred with longer treatment duration. The ORR in HCL rose from 24% at 32 weeks to 36% at 48 weeks, but that is where the similarity between the responses of CLL and HCL to ibrutinib ends. Whereas ibrutinib in CLL affects cell homing and migration, leading to a rapid release of tumor cells from proliferation niches associated with transient lymphocytosis, these effects were not observed in HCL. Furthermore, in CLL the collective effect of BTK inhibition on tumor cell homing, survival, and proliferation determines response to ibrutinib. In HCL, however, durable benefit from ibrutinib treatment was observed, even in patients with persistent phosphorylation of the BTK downstream target extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Finally, the principal mechanism of ibrutinib resistance in CLL involves BTK and PLCG2 mutations, consistent with continuous pressure on the drug target.9 In contrast, patients with HCL who developed resistance to ibrutinib displayed no such mutations. Taken together, the findings by Rogers and colleagues imply that the clinical effect of ibrutinib in patients with HCL, at least to some extent, may be independent of BTK inhibition.

The BTK-independent activity of ibrutinib is becoming a fast-expanding area of research. Although remarkably selective for BTK, ibrutinib affects several other kinases that share the same cysteine residue in the ATP-binding site, including members of the TFK family (ITK, TEC, BMX, and RLK/TXK), the EGFR family (EGFR, ErbB2/HER2, and ErbB4/HER4), and the kinases BLK and JAK3.10 Consequently, elucidating the off-target effects of ibrutinib sheds light on ibrutinib-associated toxicity.

We must not forget, however, that apart from treatment-associated toxicity, ibrutinib off-target activity may provide additional mechanisms that underpin its antitumor effect. The study by Rogers and colleagues consolidates an appreciation of the need for us to look beyond the BCR signaling–driven malignancies when considering ibrutinib as a therapeutic option. More studies are needed to fully understand how ibrutinib targets both malignant cells and its surrounding microenvironment, irrespective of BTK inhibition. Understanding the influence of ibrutinib on different target proteins will inform strategies, not only to counteract its toxicity, but also to broaden its clinical application.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal