INTRODUCTION

A major gap in US care for Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is a dearth of healthcare providers with expertise in adult SCD management. In 2014 TOVA Community Health launched a community-based primary specialty care clinic in Delaware (DE). The Delaware Department of Health and Social Services found that 96 individual adults in DE with Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) utilized hospital services 99.5% of the time for sickle cell crisis (Anderson et al., 2014). The majority of those adults lived in New Castle County, DE. The dearth of sickle cell hematologist/oncologists for adults in this county may drive them to seek recurrent care through the hospital system. Recognizing this as a nationwide public health crisis, the Delaware Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS) partnered with TOVA Community Health in 2014 to establish an adult primary specialty care clinic medical home in New Castle County, DE. This report describes the progress/impact of an integrated primary specialty clinic for adults with SCD

METHODS

Prospective/ Retrospective tracking of best practices for SCD are featured in the NIH 2014 guidelines. The staff included a hematologist with expertise in SCD, a primary care provider, an advanced practice nurse, a Social Worker (MSW), a nurse care coordinator, and a community health worker, were funded by Sickle Cell Disease Association of America (SCDAA) and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). From 2014 to 2018, integrated primary specialty care services were provided for 33 discrete patients.

RESULTS

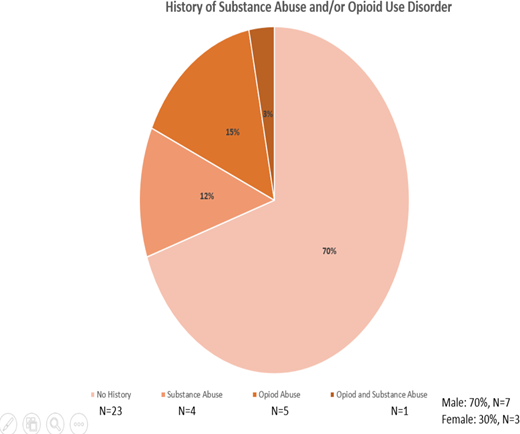

This first cohort of patients was notable for health complications that may be attributed to the lack of coordinated primary specialty sickle cell care access. Therapeutic counseling, support groups and preventive health maintenance services were measured by: outpatient visits to the clinic, access to disease modifying therapies (hydroxyurea therapy or chronic transfusion therapy), immunizations (Pneumococcal), Depression Screens and Personalized Sickle Care Plans (Table). 21 % percent of the patients had no sickle cell provider and/or hematologist/oncologist other than ED or inpatient care for the 12 months preceding their first visit to our clinic. 48% of the patients received a pneumococcal vaccine (Pneumovax 23 val - n=16/33 and Prevnar 13 - n=7/33) and three (n=3/33) received both Pneumococcal vaccines. 30% percent of the patients (n=10/33 patients) seen were offered access to HU but were not on the drug and 42% (n=14) were prescribed HU. All patients did not have a Personalized Sickle Cell Care Plan prior to receiving services at the Primary Specialty Care clinic. 12% (n=4/33) patients had a diagnosis of Substance Abuse Disorder, 15% (n=5/33) had a diagnosis of Opioid Use Disorder and 3% (n=1/33) had both Substance Abuse and Opioid Use Disorder. 70% (n= 7/10) were male and 30% (n-3/10) were female with a diagnosis of Substance Abuse and/or Opioid Use Disorder. 45% (n=15/33) had a Pain Management Agreement established within the time period at the primary specialty clinic.

CONCLUSION

The creation of an integrated practice primary specialty care clinic for adults with SCD in New Castle County, Wilmington, DE demonstrates the successful leverage of regional networks that engages an academic institution for telehealth consultation, public health, and community-based organizations to develop an adult SCD primary specialty care model. This safety net clinic provides team based primary specialty care to adults whose only option previously was the hospital and/or emergency room. Unique challenges in managing adult SCD acute and chronic pain were addressed. Overall, this is one model for access to integrated primary specialty care and behavioral health services for persons with SCD across their lifespan.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal