In the current issue of Blood, Xia et al evaluate the use of convalescent plasma for the treatment of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).1,2 SARS-CoV-2 has spurred a global crisis. To date, there are limited treatment options for COVID-19 and no proven prophylactic therapies for those who have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2.

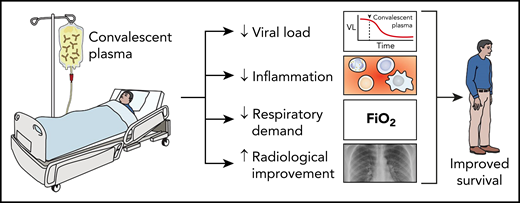

Convalescent plasma improves patient outcomes. Studies have demonstrated when convalescent plasma is given prior to the onset of critical disease in COVID-19 patients, it decreases patient’s viral load, inflammatory state, and respiratory demand and improves their outcomes with fewer fatalities. VL, viral load.

Convalescent plasma improves patient outcomes. Studies have demonstrated when convalescent plasma is given prior to the onset of critical disease in COVID-19 patients, it decreases patient’s viral load, inflammatory state, and respiratory demand and improves their outcomes with fewer fatalities. VL, viral load.

Passive antibody administration through transfusion of convalescent plasma offers the best and only short-term strategy to confer immediate immunity to susceptible individuals for COVID-19. Passive antibody therapy has been in use for over a century for both postexposure prophylaxis (eg, rabies, polio) and treatment (eg, SARS-CoV-1, Middle East respiratory syndrome, Ebola).3

Limited data suggest a clinical benefit of convalescent plasma for treating patients with COVID-19, including radiological resolution, reduction in viral loads, and improved survival in hospitalized but nonintubated patients.4,5 In New York City, a propensity score-matched control study demonstrated that convalescent plasma significantly decreased mortality among nonintubated plasma recipients, but convalescent plasma did not appear helpful for the intubated convalescent plasma recipients.6 Most recently, a randomized control trial of patients with severe disease but not those with critical disease (ie, those receiving mechanical ventilation) who received convalescent plasma showed more frequent and faster clinical improvement compared with controls. However, the trial was terminated early due to lack of eligible patients at the study sites in China because of decreasing cases there.7 All of these studies combined, however, included <150 patients treated with convalescent plasma. Convalescent plasma may be the best treatment currently available so it is critically important to assess efficacy, safety, and the subpopulations of patients who will benefit most.

Xia et al present the most extensive study to date among COVID-19 patients in the largest hospital in Wuhan, China. There were 138 patients who received convalescent plasma and 1430 control patients. Although the patients who received convalescent plasma were older and had more severe disease, convalescent plasma therapy led to a decrease in viral load, decrease in C-reactive protein concentration, radiologic improvements, and >50% decrease in mortality compared with controls (see figure). Convalescent plasma therapy did not help the sickest patients (ie, those requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and mechanical ventilation). In addition, convalescent plasma only appeared beneficial to those patients who received convalescent plasma within the first 7 weeks of diagnosis but not in those who received it later.

The US Food and Drug Administration published guidance for 3 pathways to access convalescent plasma. The primary pathway is a government-led initiative that set up the Expanded Access Program (EAP) for participating institutions under one Investigational New Drug approval and a master treatment protocol. Through the EAP, convalescent plasma has been requested for >30 000 patients in the United States, and >23 000 patients have been transfused to date.8 In response to the EAP and substantial demand for convalescent plasma, the New York Blood Center Enterprises developed a system and scaled up to collecting to >5000 units of convalescent plasma per week.9 A large analysis of the first of 5000 convalescent plasma transfusions through the EAP found virtually no adverse events attributable to the convalescent plasma treatment.10

Most recently, the outcomes of the first 20 000 patients who had been transfused 1 to 2 convalescent plasma units were reported. The 7-day mortality rate was 8.6% and higher in intensive care unit (10.5% vs 6.0%), ventilated (12.1% vs 6.2%), and septic or multiorgan failure (14.0% vs 7.6%) patients.11 Although these data further support earlier use of convalescent plasma in the disease course, it remains unknown if convalescent plasma improves outcomes compared with other treatment options.

Also, in this issue of Blood (and discussed in another Blood Commentary), Hegerova et al present a case series of 20 patients who received convalescent plasma under the EAP compared with 20 matched control patients.2 Patients who received convalescent plasma had a decrease in their body temperature, C-reactive protein concentration, and FiO2. None of the patients who received convalescent plasma within the first 7 days of hospitalization died. In the future, it is hoped, more efficacy information will be available from the thousands of patients receiving convalescent plasma through the EAP; currently the correlation between convalescent plasma antibody levels and patient outcomes is being investigated. This information is urgently needed to ensure COVID-19 patients are being best served.

The study by Xia et al, and also Hegerova et al, provides a dramatic improvement in the evidence supporting the use of convalescent plasma for patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Similar to other infections, passive antibody therapy appears to be most effective when administered early after the onset of symptoms. Convalescent plasma also appears to be safe based on few adverse events associated with the transfusion. Limitations to these studies, however, include not fully matched cases and controls. Furthermore, the studies were confounded by patients simultaneously receiving other therapies (ie, antiviral therapy, hydroxychloroquine, traditional Chinese medicine, anticoagulation, etc) Last, data on neutralizing antibody titer were not available, and antibody titers were widely variable of the transfused convalescent plasma. Consequently, well-conducted randomized controlled trails are urgently required. The clinical trials are needed to assess the subpopulations who may or may not benefit from convalescent plasma. There are a number of different protocols for various patient populations, including (1) postexposure prophylaxis to prevent infection, (2) early treatment to prevent hospitalization, (3) treatment just after hospitalization for those requiring oxygen but not yet intubated (ie, green zone), (4) severely ill patients who are already intubated, and (5) pediatric patients. As of 1 June 2020, on ClinicalTrials.gov, there are currently >80 convalescent plasma trials for COVID-19. In this time of public health crisis, institutions should collaborate and form multicenter trials to quickly determine the best treatments.

Convalescent plasma is one of the best therapies currently available to treat COVID-19. However, critical questions on timing of treatment in the disease course and dose (volume and antibody titer levels) need to be answered. These answers will also help prepare us for other passive antibody treatments (eg, hyperimmune globulin made from convalescent plasma and monoclonal antibodies). The medical community must work together to battle this deadly disease in order to determine the best therapies and reduce mortality.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.