Abstract

Background: Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) is an effective and curative treatment modality for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML), based on the strong graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect. The question about the optimal intensity of conditioning regimen of alloHCT for CML for survival outcomes is relevant, even in the era of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). However, no comparison has been attempted between outcomes after myeloablative (MAC) and reduced intensity conditioning/non-myeloablative (RIC) regimens prior to alloHCT. Using the database from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), we tried to answer the question if RIC alloHCT results in similar outcomes as MAC in patients with CML.

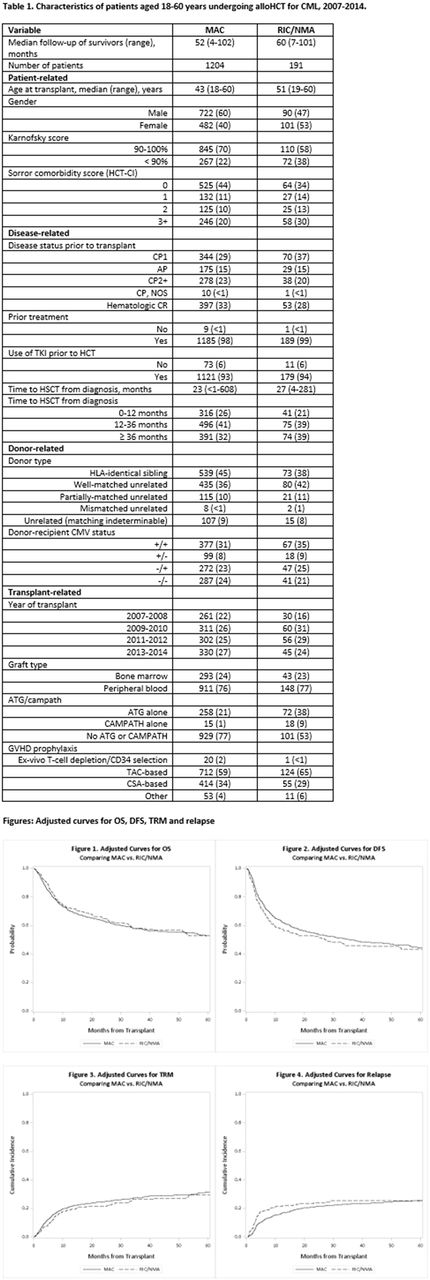

Methods: We evaluated 1395 CML patients, between the ages of 18 and 60, who received MAC (n=1204) or RIC (n=191) before alloHCT between 2007 and 2014 and were reported to CIBMTR. The disease status at transplant was divided into the following categories: hematologic complete remission (CR), chronic phase 1 (CP1), chronic phase 2 and beyond (CP2+), accelerated phase (AP). Patients in blast phase (BP) at transplant and alternative donor transplants (haploidentical and cord blood) were excluded. The primary outcome was overall survival (OS) after alloHCT. Assuming a 5-year absolute difference of 15% in favor of RIC (relative risk [RR] 1.56), the study had 92% statistical power to detect this difference if it existed.

Results: Median follow up of survivors in the MAC and RIC cohorts was 52 and 60 months, respectively. Patient, disease, and transplantation characteristics were similar with a few exceptions (Table 1). The median ages in MAC and RIC groups were 43 and 51 years, respectively. In vivo T cell depletion using anti-thymocyte globulin or alemtuzumab was used less commonly in MAC (22%) than in RIC group (47%). Multivariate analysis (MVA) showed that there was no significant difference in OS between MAC and RIC groups (p=0.87) (Fig. 1). In addition, disease-free survival (DFS) also did not differ significantly between the two groups (p=0.29) (Fig. 2). MVA failed to show any difference in transplant-related mortality (TRM) between MAC and RIC groups (Cox model p=0.95; Fine-Gray model p=0.58) (Fig. 3). In MVA, compared to MAC, RIC was associated with higher risk of relapse within 5 months of alloHCT (HR 1.85, p=0.001), but after that period, RIC patients had a trend toward lower risk of relapse than MAC (HR 0.64, p=0.09) (Fig. 4). Similar results were obtained with Fine-Gray model. The higher risk of relapse early on after RIC could be due to modest cytoreduction allowing relapse before GVL could take effect. The cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD was lower in RIC compared to MAC (HR 0.77, p=0.02). Subgroup analysis evaluating outcomes in patients who were in CP2+ or AP at transplant showed no significant difference in OS, DFS, TRM, or chronic GVHD and essentially mirrored results of the main model. Interestingly, subgroup analysis among those in CP2+ or AP showed that relapse risk was 2.3 times greater in RIC group during the first 5 months (HR 2.33, p=0.002) and afterward, a lower trend was noted (HR 0.39, p=0.10), compared to MAC.

Conclusions: Considering no differences in OS and DFS between MAC and RIC alloHCT for CML in the overall cohort and in a pre-defined subgroup analysis restricted to those in CP2+ or AP, we conclude thatRIC alloHCT is an appropriate choice for CML patients less than 60 years of age. The study showed that higher risk of relapse in the first 5 months post-RIC alloHCT did not lead to inferior DFS or OS, indicating effective salvage treatment of the relapse. In addition, a lower incidence of chronic GVHD associated with RIC is an important consideration in deciding the transplant conditioning regimen for CML.

Stuart: Cantex: Research Funding; Agios: Research Funding; ONO: Consultancy, Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Incyte: Research Funding; Astellas: Research Funding; Celator/Jazz: Research Funding; Bayer: Research Funding; Seattle Genetics: Research Funding; Sunesis: Consultancy, Honoraria, Other: Travel Support, Research Funding; MedImmune: Research Funding; Novartis: Research Funding; Amgen: Consultancy, Honoraria; Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company: Research Funding.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This icon denotes a clinically relevant abstract

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal