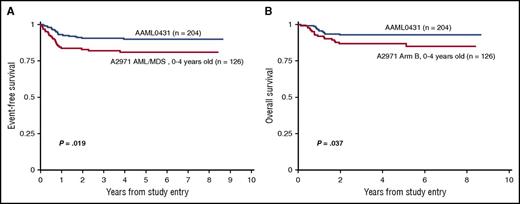

Survival curves comparing (A) event-free survival and (B) overall survival in children ages 0 to 4 years with Down syndrome treated on the Children’s Oncology Group AAML0431 trial (dark blue) vs the legacy Pediatric Oncology Group A2971 AML/MDS study (red).

Survival curves comparing (A) event-free survival and (B) overall survival in children ages 0 to 4 years with Down syndrome treated on the Children’s Oncology Group AAML0431 trial (dark blue) vs the legacy Pediatric Oncology Group A2971 AML/MDS study (red).

Children with trisomy 21/DS represent a clinically and genetically unique subset of pediatric patients with AML, with patients <4 years of age having a 500-fold increased risk of developing the disease.2 Taub et al report improved event-free survival and overall survival in a prospective cohort of children with DS that examined the impact of early intensification of cytarabine therapy and reduction of cumulative anthracycline dosing in children diagnosed between age 0 and 4 years (see figure).

ML-DS is characterized by somatic mutations in the hematopoietic transcription factor GATA1, with cooperative effects of aberrant gene expression associated with trisomy 21.3 Myeloblasts from ML-DS patients are particularly sensitive to cytosine arabinosides because of the proximity of GATA1 to the cytidine deaminase promoter.4 To determine whether this effect could be exploited without excess toxicity, patients in the 0431 study received intensified high-dose cytarabine therapy during the second induction therapy block. This treatment phase had the longest median time to neutrophil recovery (37 days), highest incidence of febrile neutropenia (29.7%), and highest frequency of sterile site bacterial infections (22.6%), highlighting the very real need for close monitoring, continued improvements in supportive care, and a better understanding of impaired host defense in ML-DS patients. Three nonrelapse deaths occurred as a result of human metapneumovirus infection, consistent with the European experience with ML-DS in which viral infections accounted for the majority of infection-related mortality.5 These observations should generate further study about differences in T-cell reconstitution and antiviral immunity in children with ML-DS.

If, as they say, the sword of truth bears 3 edges (yours, mine, and the truth), we must carefully consider how the trident of organ toxicity, infection, and antileukemia cytoreduction is wielded in this population. Children with DS have a significantly increased risk of congenital heart disease, with approximately 50% of all patients manifesting congenital structural lesions.6 It is not uncommon for them to receive a leukemia diagnosis after having received complex surgical repair or already being on long-term medical management to support cardiac function. This has substantial implications for the direct cardiotoxicity of anthracycline chemotherapy7 and the ability of these patients to meet the increased cardiac demands of infection and chemotherapy-induced anemia. The 0431 results reported here indicate that improvements in event-free survival and overall survival are maintained with a 25% reduction in total cumulative anthracycline dosing. Children with significantly reduced baseline cardiac function were excluded from the study, however. Continued longitudinal monitoring of survivors will determine whether other maneuvers to intensify therapy in the 0431 study, including cytarabine intensification and the introduction of etoposide, will introduce other long-term comorbidities.

The prognostic significance of high-resolution minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment has been demonstrated in pediatric AML patients without DS8 and was a secondary aim of the 0431 study. The authors conclude that end-induction MRD was a predictor of disease-free survival, with 92.7% survival in MRD-negative (defined as <0.01% blasts per 10 000 cells by flow cytometry) vs 76.2% in MRD-positive patients. Additional questions remain regarding how MRD levels can best be used to improve outcomes in MRD-positive patients. Identifying and intensifying therapy for patients who would not have otherwise been classified as high risk is of particular importance in ML-DS, because excess mortality from hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may limit options for children who relapse.9

With treatment modifications based on the known interactions of GATA1 with chemotherapy-associated gene regulation resulting in improved survival, what lies on the horizon for pediatric ML-DS? As with other subtypes of pediatric leukemia, next-generation molecular profiling of ML-DS myeloblasts to identify novel oncogenic drivers and in the discovery of epigenetic regulatory elements such as micro-RNAs that drive myeloid leukemogenesis10 will surely define the leading edge of targeted therapy and ensure a brighter future for children with ML-DS.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal