Abstract

Introduction

The IPSS-R (Greenberg et al, Blood 2012) achieved a more accurate definition of risk groups among patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) by using refined cytogenetic risk assessment and a more sophisticated categorization of bone marrow blast percentages and cytopenias. Like the original IPSS, the IPSS-R was developed from clinical data describing untreated MDS patients, i.e. patients receiving only best supportive care. Our investigation was conducted to see whether the IPSS-R can also predict the survival of patients receiving specific MDS treatment, as is now the case for the majority of patients.

Methods

We identified in the Duesseldorf MDS Registry 142 patients who completed treatment with either a hypomethylating agent, intensive chemotherapy, allogeneic stem cell transplantation, lenalidomide, or more than one of these therapies, and in whom the IPSS-R could be calculated at the time of diagnosis and at least once after therapy was completed. We used the product-limit method to estimate the probability of survival.

Results

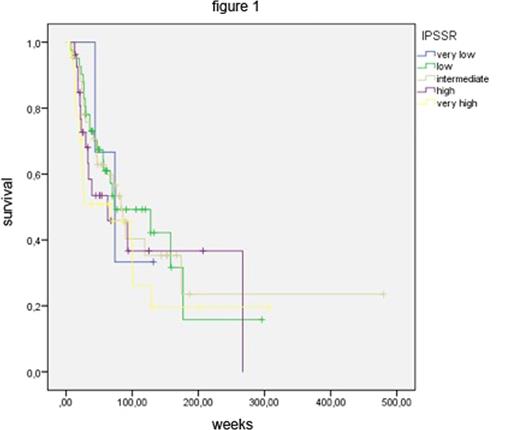

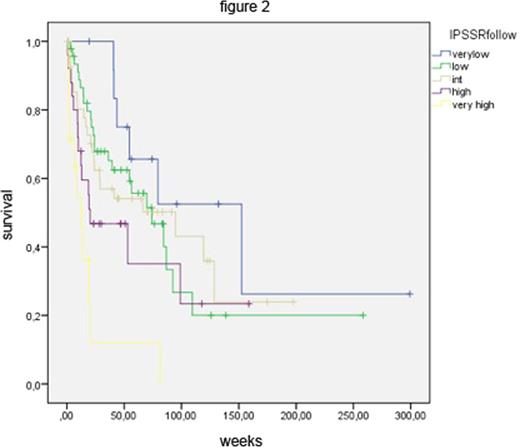

At diagnosis, the 142 MDS patients were distributed among IPSS-R risk groups as follows: 3 very low risk, 41 low risk, 43 intermediate risk, 27 high risk and 28 very high risk. Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival curves of these groups, which are statistically not significantly separate. In other words, the strong prognostic power of the IPSS-R, which has clearly been demonstrated for untreated patients, was lost in patients receiving disease-modifying treatment. We also applied the IPSS-R after finishing therapy or subsequent to stem cell transplantation. Patients were assigned to the IPSS-R risk groups based on clinical data obtained at least four weeks after treatment. This resulted in Kaplan-Meier survival curves that clearly separated IPSS-R risk groups again (Figure 2).

Conclusion

Since it was developed on a data base of untreated MDS patients, it is not surprising that, applied at the time of diagnosis, the IPSS-R is not an effective tool to assess the prognosis of patients proceeding to receive disease-modifying treatment. Nevertheless, at the time of diagnosis, the IPSS-R reliably predicts the natural course of disease and thus helps to make appropriate, risk-adapted treatment decisions.

After treatment has exerted its influence, mirrored by changes in blood counts, bone marrow blast counts and karyotypes, these changes can lead to re-categorization of patients in the IPSS-R. We demonstrate that such re-assignment is clinically meaningful, as shown by the survival curves in Figure 2. In other words, after disease-modifying treatment the IPSS-R regains its prognostic power and may again be used as an effective tool to support clinical decision making. This does not obviate the need to develop, independent of the IPSS-R, multiple treatment-specific tools to predict the response to various therapies.

Gattermann:Novartis: Consultancy, Honoraria, Other: travel, accomodation expenses, Research Funding; Celgene: Consultancy, Honoraria, Research Funding. Kobbe:Jansen: Honoraria, Other: travel support; Celgene: Honoraria, Other: travel support, Research Funding.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal