Abstract

Introduction: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is an indolent lymphoproliferative disease that mainly affects older people, the majority of whom have medical comorbidities. Fatigue is a common symptom of CLL and patients will present with varying levels of fatigue at the start of treatment. The standard of care in such patients is CD20-based chemoimmunotherapy. Among available CD20-targeting antibodies is obinutuzumab (GA101, Gazyva/Gazyvaro), a glycoengineered type 2 antibody shown to be superior to rituximab with regard to several survival endpoints. Next to the prolongation of survival, maintaining or improving quality of life - including controlling fatigue - is an important goal of chemoimmunotherapy in CLL, especially in older patients with comorbidities. Understanding fatigue in this patient population relative to other measures of health-related quality of life (HRQOL), baseline clinical variables, and treatment outcome, therefore is of considerable interest.

Methods: We studied HRQOL with a focus on fatigue in patients receiving chemoimmunotherapy within the CLL11 study. This randomized trial enrolled 663 patients, with previously untreated CLL and increased comorbidity burden, to be treated with obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil (GClb, n=333) or rituximab plus chlorambucil (RClb, n=330). The EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CLL16 questionnaires were used to capture HRQOL at baseline, during chemoimmunotherapy, and during the post-treatment period until documented disease progression. Both questionnaires assess fatigue among several other HRQOL constructs. Association of fatigue with baseline clinical and demographic variables was conducted. Means and changes in means of the QLQ-C30/CLL16 scales (including fatigue) were examined, with a 10 point change considered the limit for clinical meaningfulness. Time to clinically meaningful deterioration in fatigue between the two treatment groups was examined using Kaplan-Meier curves.

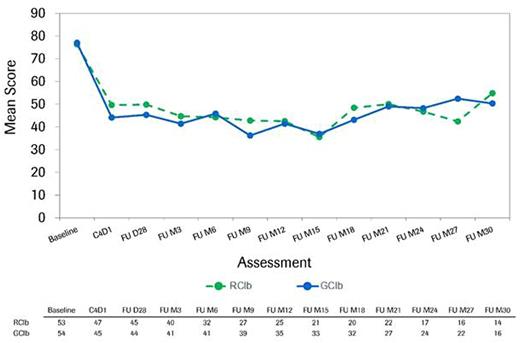

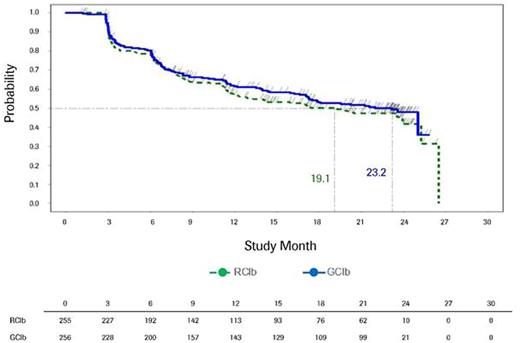

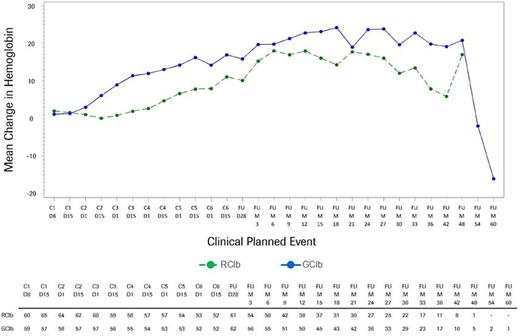

Results: Among the 663 patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy in the CLL11 study, 625 (312 in the GClb and 313 in the RClb arm) completed baseline HRQOL measures. Baseline mean HRQOL scores were similar for both treatment arms. Evaluation of fatigue quartiles for both groups revealed that those in the worst quartile were more likely to have a poorer ECOG performance status (ECOG PS score of 2 or 3), higher comorbidity burden (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale >6), higher scores on HRQOL symptom scales, and lower scores on HRQOL functioning scales at baseline. Mean hemoglobin levels at baseline were lowest in the worst fatigue quartile for both treatment groups (with the GClb arm having lower levels than the RClb arm). Over the course of treatment, HRQOL scores were similar for both treatment arms, although at several points during treatment the GClb arm reported improvement on several scales, including fatigue, appetite loss, disease effects, and global health status, that exceeded the minimal threshold for clinically meaningful difference. Among those patients in the worst fatigue cohort at baseline, clinically meaningful improvements in fatigue were observed for both treatment arms, starting at the first post-baseline assessment (Fig.1). The median time to clinically meaningful deterioration in fatigue was 23.2 months in the GClb arm and 19.1 months in the RClb arm (Fig.2). Noticeable increases in hemoglobin levels were observed by cycle (C) 2 day (D) 15 in the GClb arm and C4D15 in the RClb arm, with values continuing to increase over subsequent treatment and follow-up (FU; Fig.3).

Conclusions: These data highlight that in older patients with previously untreated CLL and comorbidities, fatigue appears to have an impact on clinical baseline variables and vice versa. The clinical benefit observed in chemoimmunotherapy with GClb or RClb is also observed in patients' HRQOL, including fatigue, particularly in those individuals with significant fatigue at baseline. In addition, GClb appears to be associated with a longer time to development of clinically meaningful fatigue than RClb, thus favoring its use in this patient population.

Longitudinal course of fatigue as assessed by QLQ-C30 fatigue scale in the worst fatigue cohort

Longitudinal course of fatigue as assessed by QLQ-C30 fatigue scale in the worst fatigue cohort

Time to deterioration in fatigue as assessed by the QLQ-C30 fatigue scale

Time to deterioration in fatigue as assessed by the QLQ-C30 fatigue scale

Mean change in hemoglobin in the worst fatigue cohort as assessed by the QLQ-C30 fatigue scale

Mean change in hemoglobin in the worst fatigue cohort as assessed by the QLQ-C30 fatigue scale

Goede:GlaxoSmithKline: Honoraria; Gilead: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Janssen: Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Roche: Consultancy, Honoraria, Other: Travel grant, Research Funding. Trask:Genentech, Inc.: Employment, Equity Ownership. Uguen:Roche: Employment. Bazeos:Roche: Employment, Other: This year I am employed by Roche full time but I am on secondment from Imperial College where I am a hematologist in training. I return there on Sept 1st. This abstract was the result of full time work at Roche and Imperial College played no part in it.. Fischer:Hoffmann-LaRoche: Other: Travel grants. Hallek:AbbVIe: Consultancy, Honoraria; Mundipharma: Consultancy, Honoraria; Glaxo-SmithKline: Consultancy, Honoraria; Gilead: Consultancy, Honoraria; Janssen: Consultancy, Honoraria, Speakers Bureau; Pharmacyclics: Consultancy, Speakers Bureau; Celgene: Consultancy, Honoraria; Roche: Consultancy, Research Funding, Speakers Bureau.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal