Abstract

Gene and cell therapy for hemophilia A requires the use of the appropriate target cell for genetic modification and, given the advances in genome editing, an approach that can be applied universally for the wide variety of genetic mutations in the coagulation factor VIII gene (F8) responsible for hemophilia A. Recent studies using two different conditional knockout mouse models showed that the principal, and possibly exclusive, source for FVIII in the circulation are endothelial cells (Everett LA et al. Blood 2014.123: 3697; Fahs SA et al. Blood 2014.123: 3706). Since endothelial cells are present in all the major organs previously thought to produce coagulation factor VIII (FVIII), these studies provide the basis for the earlier reports indicating different tissues (liver, lung, spleen, lymphatic tissue) as sources of FVIII. ECs conveniently express von Willebrand factor (vWF) that is essential for the stability of FVIII. The precursor of ECs, endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), have been isolated from adult human peripheral blood and cord blood. EPCs can readily integrate into existing vascular system upon intravenous injection. EPCs are quite rare in peripheral blood (about 20 colony forming cells per 100 mL of blood). Moreover, EPCs derived from adult peripheral blood have lower proliferative potential than those obtained from cord blood (Ingram DA. Blood. 2004. 104: 2752). In contrast, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), that are more amenable for expansion, can be readily differentiated into EPCs. Studies have also shown that iPSC-derived EPCs when injected intrahepatically in mice integrated into liver sinusoids, resulted in therapeutic levels of FVIII production (Xu D et al. PNAS 2009. 106: 808).

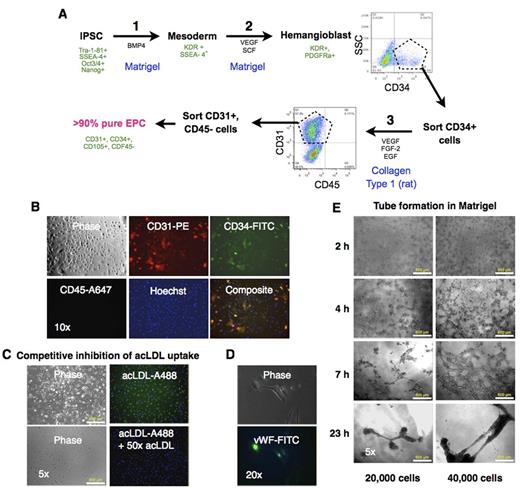

Here we describe an optimized in vitro differentiation protocol for derivation of EPCs from iPSCs. We have previously reported the generation and characterization of human iPSCs from lung fibroblasts (Srinivasakumar et al. PeerJ. 2013;1:e224). In this study we used human iPSCs generated from adult dermal fibroblasts using Yamanaka's non-integrating Epstein-Barr based episomal vectors. We used a step-wise differentiation protocol for obtaining EPCs that was a combination of a method for differentiation of iPSCs into hematopoietic progenitors (Fig A, Steps 1 & 2) to generate hemangioblasts (Niwa A et al. PLoS ONE 6(7): e22261), and a protocol for obtaining EPCs from peripheral blood (Step 3) (Mead LE et al. Current Protocols in Stem Cell Biol. 2C.1.1-2C.1.27). A sorting step after differentiation into hemangioblasts followed by a final round of sorting after step 3 yielded >90% pure population of EPC that exhibited the canonical cell surface markers: CD31 and CD34, and absence of CD45 (Fig B). The cells also took up fluorophore-conjugated acetylated LDL (acLDL-A488) that was inhibited with 50x excess of unlabeled acLDL (Fig C). Immunofluorescence staining for vWF revealed characteristic staining reminiscent of Weibel-Palade bodies in the cytoplasm (Fig D). The cells exhibited the typical tube formation ability in Matrigel (Fig E). Additional studies are needed to determine the proliferative potential of these cells and their ability to integrate into vasculature.

To address the myriad mutations shown to be responsible for hemophilia A, we have designed high efficiency dimeric guide RNAs (as part of a separate study) (Zaboikin M et al. Manuscript in preparation) for use with the CRISPR/dCas9-Fok1 system (Tsai SQ et al. Nat Biotechnol. 2014. 32:569) for precise modification at the F8 locus downstream of the first coding exon. We also showed in that study the replacement of target sequence at the site with that of a donor template sequence with desired attributes. We hypothesize that using a donor template that encodes the F8 promoter driving a functional F8 cDNA for homology directed repair at the target double stranded break site will provide an universal solution for the large variety of mutations observed in hemophilia A. Results of genome editing of iPSCs using the above mentioned CRISPR/dCas9-Fok1 system (together with the donor template) followed by the differentiation of genetically modified iPSCs into EPCs will be presented.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This icon denotes a clinically relevant abstract

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal