In this issue of Blood, Saußele et al demonstrate, in a study based on 1519 chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients, that death may be a flawed end point for the assessment of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) efficacy because, in the current era, CML patients more often die with their disease than because of it.1

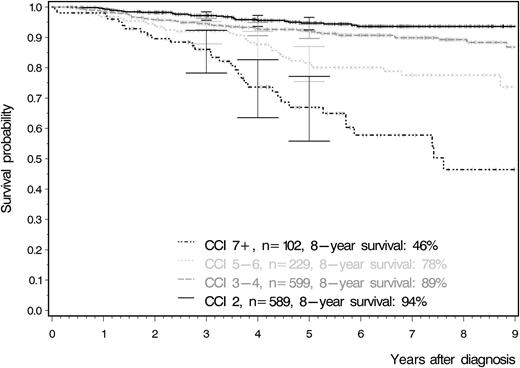

Overall survival according to the Charlson comorbidity index. This curve clearly demonstrates that patients with a larger number of comorbidities have significantly lower survival rates irrespective of their age at study entry. Adapted from Figure 4A in the article by Saußele et al that begins on page 42.

Overall survival according to the Charlson comorbidity index. This curve clearly demonstrates that patients with a larger number of comorbidities have significantly lower survival rates irrespective of their age at study entry. Adapted from Figure 4A in the article by Saußele et al that begins on page 42.

The basic tenet of trial design when evaluating new cancer therapies is that having surrogate markers of good response that correlate with favorable long-term outcomes is appropriate and pragmatic, but that the ultimate test for a new therapy is to establish improved survival. This study suggests that survival may not be the gold standard end point, at least when it comes to trials of TKIs in CML. Because, for the majority of patients, CML is now a chronic condition maintained by regular TKI therapy,2 improvements in survival have become increasingly difficult to demonstrate, requiring large studies and very long follow-up. This study found that the most powerful predictor of survival for CML patients in the large German CML Study IV trial3 was a composite measure of comorbidities (the Charlson comorbidity index)4 at diagnosis rather than the disease-specific Sokal or EUTOS prognostic scores (see figure).

Saußele et al demonstrate that there is a strong negative association between comorbidities at diagnosis and overall survival, but that comorbidities have no effect on response (ie, complete cytogenetic response and major molecular response), remission rates, and progression to advanced phases in CML. The negative association is also not due to adverse drug-related events, either hematologic or nonhematologic. They indicate therefore that survival may be an inappropriate outcome measure for specific CML treatments, as the overall survival of CML patients is now determined more by comorbidities than by their CML. With a number of different TKIs available for therapy, and patients often switching to a second- or third-line therapy, overall survival is becoming more difficult to assess, and comorbidities may indeed be the major influence.

It follows then that survival may not be the ideal end point for CML trials, because it is so strongly influenced by comorbidities that may mask real differences in disease-related outcomes. In this case, is there a better end point we could use? One obvious candidate would be to use CML-related deaths as the key end point. This would allow us to identify new therapies that actually reduced the risk of disease progression, the overwhelming cause of CML-related deaths. There are 2 potential drawbacks here. First, it is not always straightforward to determine whether a death is CML related. For instance, how do you classify the patient who does not achieve good disease control, proceeds to an allograft while still in the chronic phase, and subsequently dies of complications, or a case of sudden unexplained death? Any subjectivity in the assessment of this end point would make the analysis potentially open to influence and bias. However, a more substantial concern is that by focusing exclusively on CML-related deaths, a subtle increase in non–CML-related deaths induced by a new therapy could be overlooked. Both the Evaluating Nilotinib Efficacy and Safety in Clinical Trials—newly diagnosed patients (ENESTnd)5 and the Dasatinib versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naive CML Patients (DASISION) 6 demonstrated lower rates of progression in patients randomized to the nilotinib and dasatinib arms compared with the imatinib arms; however, both studies failed to show a significant difference in overall survival for those patients on second-generation TKIs. This was surprising because the outcome for patients who progress to blast crisis has not improved greatly in the TKI era. Therefore, why didn’t the lower transformation rate translate into improved survival for the nilotinib and dasatinib arms of these trials? Some would argue that the high background rate of non–CML-related deaths dilutes this difference in CML-related deaths, but it is also quite plausible that the lower rate of progression and consequent CML-related deaths seen with the more potent TKIs is counterbalanced by a slightly higher rate of death from other causes. Higher rates of infection and pulmonary toxicity with dasatinib and vascular toxicity with nilotinib could potentially underlie this increase in non–CML-related deaths.

A possible shortfall of this study is the restricted definition of comorbidities. The Charlson index does not take into account things such as hypertension, angina, and obesity. It is, however, a commonly used index that has been validated in numerous settings. Furthermore, because this study was based on a clinical trial, it is reasonable to assume that various trial entry criteria around comorbidities would have restricted trial access for some patients and may have also meant that the age group studied was not truly representative of clinical practice. Although this is likely to be true, one could speculate that the inclusion of these patients would have actually increased the power of these study findings rather than reduced them.

Consideration of end points such as overall survival or freedom from CML-related death may become less relevant now that the focus of CML therapy is increasingly the achievement of a stable deep molecular response, which can provide the platform for a trial of cessation. The success of the next generation of therapies for CML will likely be judged by the capacity to achieve treatment-free remission in a greater number of patients than the current approaches, rather than measuring subtle differences in survival.

This timely study by Saußele et al reminds us that the greatest danger for most patients with CML is not their leukemia but their preexisting comorbidities. Clinicians would be wise to pay just as much attention to these comorbidities as they do to the patient’s leukemic disease risk score when selecting the optimal TKI therapy and when managing CML patients in the long term.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.L.W. and T.P.H. both receive research funding and honoraria from Novartis and BMS. T.P.H. receives honoraria from Ariad.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal