Key Points

Extended apheresis platelet storage is dependent on the collection method, storage in a storage solution, and storage bag composition.

The lifespan of the platelet is not intrinsic to the cell, and platelet viability is better maintained in vitro than in vivo.

Abstract

To evaluate the poststorage viability of apheresis platelets stored for up to 18 days in 80% platelet additive solution (PAS)/20% plasma, 117 healthy subjects donated platelets using the Haemonetics MCS+, COBE Spectra (Spectra), or Trima Accel (Trima) systems. Control platelets from the same subjects were compared with their stored test PAS platelets by radiolabeling their stored and control platelets with either 51chromium or 111indium. Trima platelets met Food and Drug Administration poststorage platelet viability criteria for only 7 days vs almost 13 days for Haemonetics platelets; ie, platelet recoveries after these storage times averaged 44 ± 3% vs 49 ± 3% and survivals were 5.4 ± 0.3 vs 4.6 ± 0.3 days, respectively. The differences in storage duration are likely related to both the collection system and the storage bag. The Spectra and Trima platelets were hyperconcentrated during collection, and PAS was added, whereas the Haemonetics platelets were elutriated with PAS, which may have resulted in less collection injury. When Spectra and Trima platelets were stored in Haemonetics’ bags, poststorage viability was significantly improved. Platelet viability is better maintained in vitro than in vivo, allowing substantial increases in platelet storage times. However, implementation will require resolution of potential bacterial overgrowth during storage.

Introduction

Platelet additive solutions (PASs) have been used to store platelets since the 1980s.1,2 PAS storage of pooled buffy coat prepared platelet concentrates have long been used in Europe.3 The advantages of using a PAS for platelet storage are many including more plasma to meet patient needs or to fractionate into plasma-based products, reduce red cell hemolysis from ABO incompatible plasma, and reduce other adverse effects related to plasma transfusion.4,5

To license platelets based on poststorage radiolabeled autologous platelet viability measurements in normal subjects, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires that the lower poststorage 95% confidence limits (LCLs) for platelet recoveries are ≥66% and survivals are ≥58% of the same subject’s radiolabeled fresh recoveries and survivals, respectively.6

Methods

Study population

Healthy subjects who met allogeneic blood donor requirements were recruited between September 2000 and November 2011, and each signed a study consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol and consents were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. Between 3 and 10 normal subjects participated in each study, with fewer subjects enrolled if the initial data suggested that FDA acceptance criteria would not be met.

Experimental design

Three different apheresis systems, the COBE Spectra (Spectra) and Trima Accel (Trima) (Terumo BCT, Lakewood, CO) (these systems may be collectively referred to as Terumo BCT systems) and the Haemonetics MCS+ (Haemonetics Corporation, Braintree, MA), were used. For the Haemonetics collections, the in-line white cell leukoreduction filter was removed to give the highest cell counts to stress the system, whereas the Terumo BCT platelets were in-process leukoreduced. Haemonetics collects whole blood into a spinning centrifuge bowl, and then either plasma or PAS is pumped into the bottom of the bowl to push the supernatant platelets into a collection bag for storage.7 The Spectra has a dual-stage processing channel with the red and white cells removed in the first stage, and the platelets are concentrated in the second stage followed by transfer to a storage bag.7 The Trima has a single-stage channel where the cells separate into layers according to specific gravity, and each component leaves by its own outlet into a storage bag.7,8 All collections were within the manufacturer’s bag parameters for volume and total platelets per bag for 5- to 7-day plasma storage. However, these guidelines may not be applicable to the Plasmalyte (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) extended storage studies reported here. Both the Terumo BCT and Haemonetics bags have approximately the same surface area. The apheresis platelets were separated equally into 2 storage bags. One bag served as the control platelets that were stored for 1, 5, or 7 days in plasma or Plasmalyte, whereas platelets in the other bag (test platelets) were stored for 5 to 18 days in Plasmalyte, subsequently referred to as a PAS. For some studies, the control platelets were fresh platelets prepared from a 43-mL whole blood sample drawn on the day the subject’s stored platelets were transfused.

Platelet radiolabeling

At the end of storage, a 43-mL aliquot from both the control and the test platelets were alternately labeled with 51Cr or 111In using established techniques so that, at the end of an experiment, equal numbers of each platelet type had been labeled with both isotopes, and the platelets were transfused sequentially into their donor.9,10 Blood samples were drawn from the subject before, at 2 hours, and on days 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 after transfusion to test for radioactivity using a Packard Model 5530 γ counter (Downer’s Grove, IL). The radiolabeled data were not corrected for potential label elution or for possible red cell bound isotope,9 except for the paired fresh and test platelet studies where a day 10 sample was obtained.10 Platelet recoveries and survivals were calculated using a computerized data entry program.11

PAS platelets

During the Terumo BCT studies, it was possible to change the usual collection procedure to hyperconcentrate the platelets with resuspension in PAS.12,13 For the Haemonetics studies, the platelets were elutriated with PAS instead of plasma during collection by sterile docking a Haemonetics bag (Effluent #692) containing PAS to the collection set. The operator would unclamp and, as appropriate, clamp the tubing to the #692 bag to permit surging with PAS. A baseline sample of the subject’s plasma and from their PAS stored platelet bag were assayed for albumin to determine the concentration of PAS vs residual plasma.

In vitro platelet measurements

Platelet counts of collected products were performed on the day following collection and after storage using an ABX Hematology Analyzer (ABX Diagnostics, Irvine, CA). After storage, in vitro measurements of glucose concentration, pH at 37°C, pCO2, pO2, extent of shape change (ESC), and hypotonic shock response (HSR),14 Annexin V binding, morphology score,15 and mean platelet volume (MPV) were performed. Residual donor plasma was added to the PAS stored platelets to adjust the platelet count to 300 000/μL before performing the ESC and HSR measurements.16

Statistical methods

Summary statistics (n, mean, standard deviation, or standard error) are presented for in vivo and in vitro measures of platelet quality grouped by apheresis machine and storage interval of the test platelets. In vivo measures of platelet viability, recovery, and survival, from paired (test and control) studies were compared using a paired t-test. When paired with a fresh or 1-day stored control platelets, test platelets were evaluated to determine if they met FDA guidelines for poststorage platelet viability. The P values were not corrected for multiple comparisons.

Results

Effect of PAS concentration on poststorage platelet viability

Ten Haemonetics collections were stored for 7 days with PAS concentrations between 50% and 82% to determine the optimum PAS concentration. With lower PAS concentrations between 50% and 67% (n = 5), recoveries averaged 65 ± 18% and survivals averaged 5.7 ± 0.5 days, and, with higher concentrations of 77% to 82%, recoveries averaged 63 ± 11% and survivals averaged 6.2 ± 0.7 days (n = 5), with no trends based on PAS concentrations. A targeted 80% PAS concentration was used for all studies.

Haemonetics platelets

In vivo data

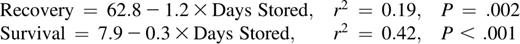

There were no significant differences between each subject’s paired plasma and PAS stored platelets at 5 and 7 days of storage except for 7-day PAS recoveries, which were 52 ± 3% vs 44 ± 5% for plasma stored platelets (P < .01; Table 1). With the 9- to 18-day PAS storage studies, the guidelines for using paired 1-day plasma stored or fresh platelets as controls were established. There were no significant differences in poststorage results for 9-day PAS stored compared with 1-day plasma stored platelets. For PAS platelets stored for ≥13 days, there were significant decreases in both platelet recoveries and survivals compared with 1-day stored or fresh platelets. PAS stored platelet recoveries and survivals declined progressively over storage times of 5 to 18 days (Figure 1A-B). The equations for the regression lines are as follows:

In vivo paired recoveries and survivals of autologous radiolabeled Haemonetics, Spectra, and Trima apheresis platelets

| N . | Control platelets . | Test PAS platelets . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storage solution . | Storage time (days) . | Platelet . | Storage time (days) . | Platelet . | |||||

| Recoveries (%) . | Survivals (days) . | Recoveries (%) . | Percent of control . | Survivals (days) . | Percent of control . | ||||

| Haemonetics apheresis platelets | |||||||||

| 6 | Plasma | 5 | 59 ± 7 | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 5 | 59 ± 5 | 102 ± 6 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 100 ± 13 |

| 10 | Plasma | 7 | 44 ± 5 | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 7 | 52 ± 3a | 130 ± 12 | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 171 ± 49 |

| 4 | Plasma | 1 | 67 ± 4 | 7.6 ± 1.1 | 9 | 55 ± 5 | 82 ± 10 | 6.6 ± 0.6 | 93 ± 19 |

| 10 | Plasma | 1 | 67 ± 4 | 7.0 ± 0.6 | 13 | 49 ± 3a | 73 ± 4 | 4.6 ± 0.3a | 69 ± 6 |

| 10 | Plasma | 1 | 65 ± 4 | 7.4 ± 0.6 | 14 | 43 ± 3a | 67 ± 4 | 4.2 ± 0.5a | 57 ± 6 |

| 3 | None | Fresh | 64 ± 9 | 8.2 ± 1.3 | 15 | 57 ± 3 | 95 ± 14 | 3.4 ± 0.3a | 50 ± 5 |

| 7 | None | Fresh | 48 ± 6 | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 15b | 24 ± 3a | 55 ± 8 | 2.2 ± 0.2a | 26 ± 2 |

| 3 | None | Fresh | 68 ± 4 | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 17 | 37 ± 3c | 55 ± 5 | 3.1 ± 0.6a | 50 ± 5 |

| 3 | None | Fresh | 69 ± 3 | 7.8 ± 0.9 | 18 | 43 ± 2a | 62 ± 2 | 3.6 ± 1.0c | 46 ± 10 |

| Spectra apheresis platelets | |||||||||

| 3 | PAS | 1 | 61 ± 6 | 7.3 ± 1.5 | 7 | 49 ± 6a | 77 ± 4 | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 66 ± 3 |

| 5 | PAS | 5 | 67 ± 4 | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 7 | 60 ± 2 | 91 ± 4 | 5.3 ± 0.5c | 81 ± 5 |

| 7 | Plasma | 7 | 52 ± 4 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 7d | 37 ± 8c | 68 ± 13 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 71 ± 16 |

| 5 | Plasma | 5 | 55 ± 6 | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 8e | 45 ± 8c | 80 ± 8 | 4.0 ± 0.8c | 60 ± 12 |

| 5 | Plasma | 5 | 50 ± 5 | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 9f | 24 ± 6c | 49 ± 13 | 3.2 ± 1.1c | 52 ± 18 |

| 5g | PAS | 13 | 40 ± 5 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 13h | 41 ± 7 | 110 ± 20 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 320 ± 109 |

| Trima apheresis platelets | |||||||||

| 9 | None | Fresh | 58 ± 5 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | 7 | 44 ± 3a | 77 ± 4 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 66 ± 3 |

| 8 | None | Fresh | 54 ± 4 | 7.7 ± 0.4 | 9i | 29 ± 7a | 54 ± 12 | 3.4 ± 0.6a | 46 ± 8 |

| 10 | None | Fresh | 57 ± 4 | 8.5 ± 0.2 | 9h | 44 ± 4a | 78 ± 5 | 5.0 ± 0.2a | 59 ± 2 |

| 2 | None | Fresh | 64, 35 | 8.4, 7.5 | 13j | 3, 17 | 5, 49 | 0.6, 2.3 | 7, 13 |

| N . | Control platelets . | Test PAS platelets . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storage solution . | Storage time (days) . | Platelet . | Storage time (days) . | Platelet . | |||||

| Recoveries (%) . | Survivals (days) . | Recoveries (%) . | Percent of control . | Survivals (days) . | Percent of control . | ||||

| Haemonetics apheresis platelets | |||||||||

| 6 | Plasma | 5 | 59 ± 7 | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 5 | 59 ± 5 | 102 ± 6 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 100 ± 13 |

| 10 | Plasma | 7 | 44 ± 5 | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 7 | 52 ± 3a | 130 ± 12 | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 171 ± 49 |

| 4 | Plasma | 1 | 67 ± 4 | 7.6 ± 1.1 | 9 | 55 ± 5 | 82 ± 10 | 6.6 ± 0.6 | 93 ± 19 |

| 10 | Plasma | 1 | 67 ± 4 | 7.0 ± 0.6 | 13 | 49 ± 3a | 73 ± 4 | 4.6 ± 0.3a | 69 ± 6 |

| 10 | Plasma | 1 | 65 ± 4 | 7.4 ± 0.6 | 14 | 43 ± 3a | 67 ± 4 | 4.2 ± 0.5a | 57 ± 6 |

| 3 | None | Fresh | 64 ± 9 | 8.2 ± 1.3 | 15 | 57 ± 3 | 95 ± 14 | 3.4 ± 0.3a | 50 ± 5 |

| 7 | None | Fresh | 48 ± 6 | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 15b | 24 ± 3a | 55 ± 8 | 2.2 ± 0.2a | 26 ± 2 |

| 3 | None | Fresh | 68 ± 4 | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 17 | 37 ± 3c | 55 ± 5 | 3.1 ± 0.6a | 50 ± 5 |

| 3 | None | Fresh | 69 ± 3 | 7.8 ± 0.9 | 18 | 43 ± 2a | 62 ± 2 | 3.6 ± 1.0c | 46 ± 10 |

| Spectra apheresis platelets | |||||||||

| 3 | PAS | 1 | 61 ± 6 | 7.3 ± 1.5 | 7 | 49 ± 6a | 77 ± 4 | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 66 ± 3 |

| 5 | PAS | 5 | 67 ± 4 | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 7 | 60 ± 2 | 91 ± 4 | 5.3 ± 0.5c | 81 ± 5 |

| 7 | Plasma | 7 | 52 ± 4 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 7d | 37 ± 8c | 68 ± 13 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 71 ± 16 |

| 5 | Plasma | 5 | 55 ± 6 | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 8e | 45 ± 8c | 80 ± 8 | 4.0 ± 0.8c | 60 ± 12 |

| 5 | Plasma | 5 | 50 ± 5 | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 9f | 24 ± 6c | 49 ± 13 | 3.2 ± 1.1c | 52 ± 18 |

| 5g | PAS | 13 | 40 ± 5 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 13h | 41 ± 7 | 110 ± 20 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 320 ± 109 |

| Trima apheresis platelets | |||||||||

| 9 | None | Fresh | 58 ± 5 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | 7 | 44 ± 3a | 77 ± 4 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 66 ± 3 |

| 8 | None | Fresh | 54 ± 4 | 7.7 ± 0.4 | 9i | 29 ± 7a | 54 ± 12 | 3.4 ± 0.6a | 46 ± 8 |

| 10 | None | Fresh | 57 ± 4 | 8.5 ± 0.2 | 9h | 44 ± 4a | 78 ± 5 | 5.0 ± 0.2a | 59 ± 2 |

| 2 | None | Fresh | 64, 35 | 8.4, 7.5 | 13j | 3, 17 | 5, 49 | 0.6, 2.3 | 7, 13 |

Fresh platelets were prepared from a blood sample drawn from the donor on the day the stored platelets were injected. Percent of control results were determined by dividing the test results by the control × 100. Data are given as the average ± 1 standard error.

P < .01. P values for PAS platelet recoveries and survivals are based on the differences between the PAS data and the control platelet data for each study.

These platelets were stored in Haemonetics CPP bags vs all other Haemonetics collection studies that were stored in Haemonetics CLX bags.

P < .05. P values for PAS platelet recoveries and survivals are based on the differences between the PAS data and the control platelet data for each study.

Four units had poststorage pHs of ≤6.0 with platelet recoveries of 57%, 18%, 17%, and 9% and associated survivals of 1.7, 2.3, 2.2, and 2.9 days, respectively.

One unit had poststorage pH of 6.3 and platelet recovery of 24% and survival of 2.6 days.

Three units had poststorage pHs of 6.4, 6.3, and 5.7 with associated platelet recoveries of 8%, 13%, and 28% and survivals of 1.6, 1.7, and 1.1 days, respectively.

One collection not injected as pH <6.0 for both bags at the end of storage.

These Terumo BCT platelets were stored in Haemonetics CLX rather than Terumo BCT bags.

One unit not injected as poststorage pH <6.0. Two other units both had poststorage pHs of 6.1 and recoveries of 2% and 3% and survivals of 1.7 and 0.5 days, respectively.

One unit with post-storage pH of 6.4 had a platelet recovery of 3% and platelet survival of 0.6 days.

Recoveries and survivals of stored apheresis platelets. (A) Recoveries of Haemonetics, Spectra, and Trima platelets stored for 1 to 18 days. (B) Survivals of Haemonetics, Spectra, and Trima platelets stored for 1 to 18 days. ●, data for Haemonetics stored platelets in CLX bags; ▲, for Spectra stored platelets; ▪, for Trima stored platelets. All data are given for platelets stored in each system’s own bags. Data are given as average ±1 standard error.

Recoveries and survivals of stored apheresis platelets. (A) Recoveries of Haemonetics, Spectra, and Trima platelets stored for 1 to 18 days. (B) Survivals of Haemonetics, Spectra, and Trima platelets stored for 1 to 18 days. ●, data for Haemonetics stored platelets in CLX bags; ▲, for Spectra stored platelets; ▪, for Trima stored platelets. All data are given for platelets stored in each system’s own bags. Data are given as average ±1 standard error.

For some of the 15-day storage studies, the Haemonetics bags had changed from CLX (polyvinyl-chloride [PVC] with tri-[2-ethylhexyl] trimillitate plasticizer) to CPP (PVC with tributyl citrate plasticizer). When platelets were stored for 15 days in the CLX vs the CPP bags, viability was significantly decreased; ie, platelet recoveries were 57 ± 5% vs 24 ± 7% (P < .001), and survivals were 3.4 ± 0.5 vs 2.2 ± 0.4 days (P = .004), respectively.

In vitro data

Storage intervals of 14 days or more showed unacceptable decreases in platelet counts compared with day 1 of 10% to 20% (Table 2). Glucose concentrations were very low even with only 9 days of storage. Morphology scores were relatively stable, whereas Annexin V binding increased, and ESC values decreased over storage time. HSR values also decreased but not until ≥14 days of storage. Poststorage pHs were stable, and none were <7.0.

In vitro assays of Haemonetics, Spectra, and Trima apheresis platelets stored in PAS

| N . | Storage time (days) . | Donor’s platelet count (μL) . | Unit volume (mL) . | Total platelet count (×1011) . | PAS (%) . | Glucose (mgm/dL)* . | MPV . | Morphology score . | Annexin V binding (%) . | ESC (%) . | HSR (%) . | pH . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 . | Test day . | Day 1 . | Test day . | |||||||||||

| Haemonetics apheresis platelets | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | 5 | 240 000 ± 29 000 | 189 ± 23 | ND | 1.76 ± 0.46 | 78 ± 7 | ND | ND | ND | 229 ± 14 | 16 ± 2 | 26 ± 5 | 77 ± 9 | 7.1 ± 0.1 |

| 9 | 7 | 232 000 ± 51 000 | 215 ± 23 | ND | 2.02 ± 0.43 | 69 ± 12 | ND | ND | ND | 250 ± 26 | 17 ± 7 | 17 ± 3 | 70 ± 14 | 7.1 ± 0.6 |

| 4 | 9 | 288 000 ± 39 000 | 217 ± 53 | 2.65 ± 0.70 | 2.74 ± 0.69 | 79 ± 3 | 77 ± 10 | 5.5 ± 6.1 | ND | 325 ± 35 | 23 ± 5 | 18 ± 3 | 87 ± 7 | 7.4 ± 0.2 |

| 10 | 13 | 234 000 ± 31 000 | 258 ± 28 | 2.59 ± 0.58 | 2.51 ± 0.53 | 81 ± 1 | 74 ± 7 | 7.0 ± 15 | 6.9 ± 1.1 | 265 ± 48 | 26 ± 14 | 13 ± 5 | 94 ± 7 | 7.4 ± 0.2 |

| 10 | 14 | 215 000 ± 45 000 | 263 ± 47 | 2.22 ± 0.53 | 2.00 ± 0.47 | 82 ± 1 | 74 ± 1 | ND | 6.7 ± 0.7 | 252 ± 52 | 34 ± 10 | 11 ± 3 | 66 ± 19 | 7.4 ± 0.2 |

| 3 | 15 | 245 000 ± 43 000 | 200 ± 48 | 2.33 ± 0.92 | 2.04 ± 0.58 | 80 ± 2 | 76 ± 2 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 7.5 ± 0.8 | 220 ± 25 | 33 ± 6 | 9 ± 5 | 67 ± 14 | 7.5 ± 0.1 |

| 8 | 15† | 254 000 ± 73 000 | 230 ± 56 | 2.26 ± 0.63 | 1.83 ± 0.72 | 76 ± 4 | 81 ± 9 | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 8.0 ± 0.5 | 245 ± 46 | 40 ± 15 | 4 ± 3 | 25 ± 11 | 7.5 ± 0.3 |

| 3 | 17 | 269 000 ± 67 000 | 218 ± 20 | 2.88 ± 0.65 | 2.56 ± 0.84 | 82 ± 3 | ND | ND | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 197 ± 10 | 35 ± 11 | 10 ± 6 | 61 ± 15 | 7.7 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | 18 | 242 000 ± 56 000 | 252 ± 78 | 2.95 ± 0.35 | 2.27 ± 0.75 | 78 ± 4 | 72 ± 3 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 7.3 ± 0.3 | 225 ± 56 | 32 ± 21 | 9 ± 6 | 29 ± 14 | 7.5 ± 0.2 |

| Spectra apheresis platelets | ||||||||||||||

| 3 | ≤1 | 194 000 ± 1,000 | 275 ± 24 | 2.36 ± 0.2 | ND | 80 ± 1 | ND | 68 ± 6 | ND | 368 ± 6 | 7 ± 2 | 16 ± 1 | 64 ± 13 | 7.2 ± 0.2 |

| 5 | 5 | 280 000 ± 68 000 | 250 ± 22 | ND | 2.73 ± 0.46 | 78 ± 2 | ND | 49 ± 11 | ND | 298 ± 50 | 10 ± 3 | 13 ± 5 | 63 ± 9 | ND |

| 15 | 7 | 242 000 ± 58 000 | 276 ± 46 | 2.38 ± 0.12 | 2.34 ± 0.69 | 80 ± 5 | ND | 31 ± 30 | ND | 240 ± 107 | 29 ± 26 | 11 ± 4 | 54 ± 15 | 6.7 ± 0.5 |

| 5 | 8 | 252 000 ± 128 000 | 268 ± 27 | 2.17 ± 1.0 | 2.21 ± 0.88 | 80 ± 1 | ND | 16 ± 16 | ND | 296 ± 58 | 28 ± 6 | 9 ± 3 | 50 ± 16 | 7.1 ± 0.6 |

| 5 | 9 | 225 000 ± 43 000 | 261 ± 67 | ND | 1.80 ± 1.1 | 80 ± 1 | ND | 3 ± 7 | ND | 233 ± 46 | 61 ± 30 | ND | 31 ± 24 | 6.6 ± 0.7 |

| 6 | 13 | 228 000 ± 8,000 | 268 ± 11 | 2.16 ± 0.10 | 1.81 ± 0.1 | 84 ± 1 | ND | ND | 8 ± 0.7 | 240 ± 14 | 52 ± 13 | 8 ± 2 | 36 ± 4 | 7.1 ± 0.2 |

| 6 | 13‡ | 228 000 ± 8,000 | 288 ± 13 | 2.14 ± 0.12 | 2.09 ± 0.1 | 84 ± 1 | ND | ND | 8 ± 0.8 | 251 ± 17 | 44 ± 15 | 7 ± 1 | 45 ± 4 | 6.9 ± 0.2 |

| Trima apheresis platelets | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | 7 | 261 000 ± 81 000 | 297 ± 11 | 2.37 ± 0.62 | 2.34 ± 0.60 | 83 ± 1 | ND | 29 ± 15 | 7 ± 0.7 | 258 ± 38 | 14 ± 6 | 13 ± 3 | 38 ± 28 | 6.8 ± 0.2 |

| 8 | 9 | 300 000 ± 89 000 | 311 ± 31 | 2.16 ± 0.56 | 2.10 ± 0.61 | 83 ± 4 | ND | 11 ± 13 | 7 ± 0.6 | 193 ± 186 | 26 ± 15 | 9 ± 5 | 36 ± 23 | 6.5 ± 0.3 |

| 10 | 9‡ | 257 000 ± 40 000 | 298 ± 12 | 2.49 ± 0.62 | 2.38 ± 0.56 | 82 ± 2 | ND | 19 ± 16 | 7 ± 0.4 | 302 ± 19 | 16 ± 6 | 12 ± 2 | 43 ± 11 | 6.8 ± 0.2 |

| N . | Storage time (days) . | Donor’s platelet count (μL) . | Unit volume (mL) . | Total platelet count (×1011) . | PAS (%) . | Glucose (mgm/dL)* . | MPV . | Morphology score . | Annexin V binding (%) . | ESC (%) . | HSR (%) . | pH . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 . | Test day . | Day 1 . | Test day . | |||||||||||

| Haemonetics apheresis platelets | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | 5 | 240 000 ± 29 000 | 189 ± 23 | ND | 1.76 ± 0.46 | 78 ± 7 | ND | ND | ND | 229 ± 14 | 16 ± 2 | 26 ± 5 | 77 ± 9 | 7.1 ± 0.1 |

| 9 | 7 | 232 000 ± 51 000 | 215 ± 23 | ND | 2.02 ± 0.43 | 69 ± 12 | ND | ND | ND | 250 ± 26 | 17 ± 7 | 17 ± 3 | 70 ± 14 | 7.1 ± 0.6 |

| 4 | 9 | 288 000 ± 39 000 | 217 ± 53 | 2.65 ± 0.70 | 2.74 ± 0.69 | 79 ± 3 | 77 ± 10 | 5.5 ± 6.1 | ND | 325 ± 35 | 23 ± 5 | 18 ± 3 | 87 ± 7 | 7.4 ± 0.2 |

| 10 | 13 | 234 000 ± 31 000 | 258 ± 28 | 2.59 ± 0.58 | 2.51 ± 0.53 | 81 ± 1 | 74 ± 7 | 7.0 ± 15 | 6.9 ± 1.1 | 265 ± 48 | 26 ± 14 | 13 ± 5 | 94 ± 7 | 7.4 ± 0.2 |

| 10 | 14 | 215 000 ± 45 000 | 263 ± 47 | 2.22 ± 0.53 | 2.00 ± 0.47 | 82 ± 1 | 74 ± 1 | ND | 6.7 ± 0.7 | 252 ± 52 | 34 ± 10 | 11 ± 3 | 66 ± 19 | 7.4 ± 0.2 |

| 3 | 15 | 245 000 ± 43 000 | 200 ± 48 | 2.33 ± 0.92 | 2.04 ± 0.58 | 80 ± 2 | 76 ± 2 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 7.5 ± 0.8 | 220 ± 25 | 33 ± 6 | 9 ± 5 | 67 ± 14 | 7.5 ± 0.1 |

| 8 | 15† | 254 000 ± 73 000 | 230 ± 56 | 2.26 ± 0.63 | 1.83 ± 0.72 | 76 ± 4 | 81 ± 9 | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 8.0 ± 0.5 | 245 ± 46 | 40 ± 15 | 4 ± 3 | 25 ± 11 | 7.5 ± 0.3 |

| 3 | 17 | 269 000 ± 67 000 | 218 ± 20 | 2.88 ± 0.65 | 2.56 ± 0.84 | 82 ± 3 | ND | ND | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 197 ± 10 | 35 ± 11 | 10 ± 6 | 61 ± 15 | 7.7 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | 18 | 242 000 ± 56 000 | 252 ± 78 | 2.95 ± 0.35 | 2.27 ± 0.75 | 78 ± 4 | 72 ± 3 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 7.3 ± 0.3 | 225 ± 56 | 32 ± 21 | 9 ± 6 | 29 ± 14 | 7.5 ± 0.2 |

| Spectra apheresis platelets | ||||||||||||||

| 3 | ≤1 | 194 000 ± 1,000 | 275 ± 24 | 2.36 ± 0.2 | ND | 80 ± 1 | ND | 68 ± 6 | ND | 368 ± 6 | 7 ± 2 | 16 ± 1 | 64 ± 13 | 7.2 ± 0.2 |

| 5 | 5 | 280 000 ± 68 000 | 250 ± 22 | ND | 2.73 ± 0.46 | 78 ± 2 | ND | 49 ± 11 | ND | 298 ± 50 | 10 ± 3 | 13 ± 5 | 63 ± 9 | ND |

| 15 | 7 | 242 000 ± 58 000 | 276 ± 46 | 2.38 ± 0.12 | 2.34 ± 0.69 | 80 ± 5 | ND | 31 ± 30 | ND | 240 ± 107 | 29 ± 26 | 11 ± 4 | 54 ± 15 | 6.7 ± 0.5 |

| 5 | 8 | 252 000 ± 128 000 | 268 ± 27 | 2.17 ± 1.0 | 2.21 ± 0.88 | 80 ± 1 | ND | 16 ± 16 | ND | 296 ± 58 | 28 ± 6 | 9 ± 3 | 50 ± 16 | 7.1 ± 0.6 |

| 5 | 9 | 225 000 ± 43 000 | 261 ± 67 | ND | 1.80 ± 1.1 | 80 ± 1 | ND | 3 ± 7 | ND | 233 ± 46 | 61 ± 30 | ND | 31 ± 24 | 6.6 ± 0.7 |

| 6 | 13 | 228 000 ± 8,000 | 268 ± 11 | 2.16 ± 0.10 | 1.81 ± 0.1 | 84 ± 1 | ND | ND | 8 ± 0.7 | 240 ± 14 | 52 ± 13 | 8 ± 2 | 36 ± 4 | 7.1 ± 0.2 |

| 6 | 13‡ | 228 000 ± 8,000 | 288 ± 13 | 2.14 ± 0.12 | 2.09 ± 0.1 | 84 ± 1 | ND | ND | 8 ± 0.8 | 251 ± 17 | 44 ± 15 | 7 ± 1 | 45 ± 4 | 6.9 ± 0.2 |

| Trima apheresis platelets | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | 7 | 261 000 ± 81 000 | 297 ± 11 | 2.37 ± 0.62 | 2.34 ± 0.60 | 83 ± 1 | ND | 29 ± 15 | 7 ± 0.7 | 258 ± 38 | 14 ± 6 | 13 ± 3 | 38 ± 28 | 6.8 ± 0.2 |

| 8 | 9 | 300 000 ± 89 000 | 311 ± 31 | 2.16 ± 0.56 | 2.10 ± 0.61 | 83 ± 4 | ND | 11 ± 13 | 7 ± 0.6 | 193 ± 186 | 26 ± 15 | 9 ± 5 | 36 ± 23 | 6.5 ± 0.3 |

| 10 | 9‡ | 257 000 ± 40 000 | 298 ± 12 | 2.49 ± 0.62 | 2.38 ± 0.56 | 82 ± 2 | ND | 19 ± 16 | 7 ± 0.4 | 302 ± 19 | 16 ± 6 | 12 ± 2 | 43 ± 11 | 6.8 ± 0.2 |

Data are given as the average ± 1 standard deviation. ND, not done.

Glucose levels can be accurately measured to 0 mgm/dL.

These platelets were stored in Haemonetics CPP bags vs all other studies that were stored in Haemonetics CLX bags.

Platelets stored in Haemonetics CLX bags.

Spectra platelets

In vivo data

These studies were done before the FDA guidelines for platelet storage were established, and a variety of controls was used. PAS vs plasma-stored platelets at 7 days gave platelet recoveries of 37 ± 8% vs 52 ± 4%, respectively (P = .05), whereas platelet survivals were not significantly different (Table 1). Eight- and 9-day PAS-stored platelets were compared with 5-day plasma-stored platelets, and both the PAS recoveries and survivals were significantly less for all comparisons (P < .05). There were progressive decreases in both platelet recoveries and survivals over storage time (Figure 1A-B). Studies were not extended beyond 9 days as platelet recoveries averaged only 24 ± 6% and survivals averaged only 3.2 ± 1.1 days.

Because the results of the Spectra platelets in PAS were so inferior to the Haemonetics platelets after only 9 days (Table 1), Spectra platelets from 6 subjects were stored for 13 days: half in a Terumo BCT storage bag (PVC with n-Butyryl tri-n-hexyl citrate as the plasticizer) and half in a Haemonetics CLX bag. This experiment was done to determine whether the decreased viability of the Spectra platelets in PAS was due to the collection method or the storage bag. Recoveries and survivals of the platelets stored in the Terumo BCT and Haemonetics bags were 40 ± 5% and 41 ± 7% (P = .89) and survivals were 2.2 ± 0.5 and 4.9 ± 0.8 days (P = .06), respectively. These data suggest that at least some of the differences in results between the 2 systems may be related to the storage bag.

In vitro data

As with the Haemonetics data, by 9 days of storage, there is almost no residual glucose (Table 2). Morphology scores were relatively stable between 5 and 13 days of storage, Annexin V binding increased, and ESC and HSR decreased over storage time.

Trima platelets

In vivo data

To further explore the effects of the collection method, we evaluated the Trima system whose collection method differs from the Spectra system.7,8 As the survival of Spectra platelets differed from Haemonetics by 7 days (Table 3), we evaluated Trima platelets stored for 7, 9, and 13 days compared with fresh platelets. There were no differences between the Spectra and Trima systems at any storage time (Table 1; Figure 1A-B). Based on the improved results when Spectra platelets were stored in Haemonetics bags, Trima platelets were stored in Haemonetics bags for 9 days with significant improvements compared with Terumo BCT bags; ie, recoveries averaged 44 ± 4% vs 29 ± 7%, P = .05, and survivals averaged 5.0 ± 0.2 vs 3.4 ± 0.6 days, P = .01, respectively (Table 1). However, compared with 9-day Haemonetics platelets, Trima survivals in Haemonetics bags were still less (P = .01; Table 3).

In vivo comparisons of Haemonetics, Spectra, and Trima apheresis platelets stored in PAS for the same times

| Collection machine . | N . | Storage bag . | Storage time (days) . | Platelet recoveries (%) . | P value (H vs S or T) . | Platelet survivals (days) . | P value (H vs S or T) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemonetics (H) | 10 | H | 7 | 52 ± 3 | — | 6.0 ± 0.3 | — |

| Spectra (S) | 15 | T | 7 | 49 ± 5 | .71 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | .05 |

| Trima (T) | 9 | T | 7 | 44 ± 3 | .06 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | .74 |

| Haemonetics | 4 | H | 9 | 55 ± 5 | — | 6.6 ± 0.6 | — |

| Spectra | 5 | T | 9 | 24 ± 6 | .007 | 3.2 ± 1.1 | .05 |

| Trima | 8 | T | 9 | 29 ± 7 | .03 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | .006 |

| Trima | 10 | H | 9 | 44 ± 4 | .20 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | .01 |

| Haemonetics | 10 | H | 13 | 49 ± 3 | — | 4.6 ± 0.3 | — |

| Spectra* | 6 | T | 13 | 40 ± 5 | .14 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | .002 |

| Spectra* | 6 | H | 13 | 41 ± 7 | .25 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | .77 |

| Collection machine . | N . | Storage bag . | Storage time (days) . | Platelet recoveries (%) . | P value (H vs S or T) . | Platelet survivals (days) . | P value (H vs S or T) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemonetics (H) | 10 | H | 7 | 52 ± 3 | — | 6.0 ± 0.3 | — |

| Spectra (S) | 15 | T | 7 | 49 ± 5 | .71 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | .05 |

| Trima (T) | 9 | T | 7 | 44 ± 3 | .06 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | .74 |

| Haemonetics | 4 | H | 9 | 55 ± 5 | — | 6.6 ± 0.6 | — |

| Spectra | 5 | T | 9 | 24 ± 6 | .007 | 3.2 ± 1.1 | .05 |

| Trima | 8 | T | 9 | 29 ± 7 | .03 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | .006 |

| Trima | 10 | H | 9 | 44 ± 4 | .20 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | .01 |

| Haemonetics | 10 | H | 13 | 49 ± 3 | — | 4.6 ± 0.3 | — |

| Spectra* | 6 | T | 13 | 40 ± 5 | .14 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | .002 |

| Spectra* | 6 | H | 13 | 41 ± 7 | .25 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | .77 |

Data are given as the average ± 1 standard error. The same bags were used to store both Spectra and Trima collected platelets. H, Haemonetics CLX; T, Terumo BCT.

These were paired observations from the same donor’s collection stored in either C or T bags.

In vitro data

Because the Trima platelets were stored for only 7 and 9 days, neither trends in the data nor differences from the Spectra platelets could be determined (Table 2). However, the results appeared better when the platelets were stored for 9 days in Haemonetics vs Terumo bags.

Viability comparisons between PAS-stored Haemonetics, Spectra, and Trima platelets

At 7 days, the recoveries of the Haemonetics, Spectra, and Trima stored platelets were not significantly different, whereas survivals were better for Haemonetics compared with Spectra platelets (P = .05) but not for Trima platelets (P = .74) (Table 3). At 9 days, Haemonetics recoveries and survivals were significantly better than both the Spectra and Trima platelets (P = .007 and .03, respectively) and survivals (P = .05 and .006, respectively). At 13 days, Haemonetics recoveries did not differ from Spectra, but survivals were significantly better (P = .002).

When Trima and Spectra platelets were stored in Haemonetics bags for 9 or 13 days, respectively, platelet recoveries were not different than similarly stored Haemonetics platelets. However, platelet survivals were significantly less for Trima stored platelets at 9 days (P = .01) but not for 13-day stored Spectra platelets.

Maximum storage duration of platelets that meet FDA poststorage viability guidelines

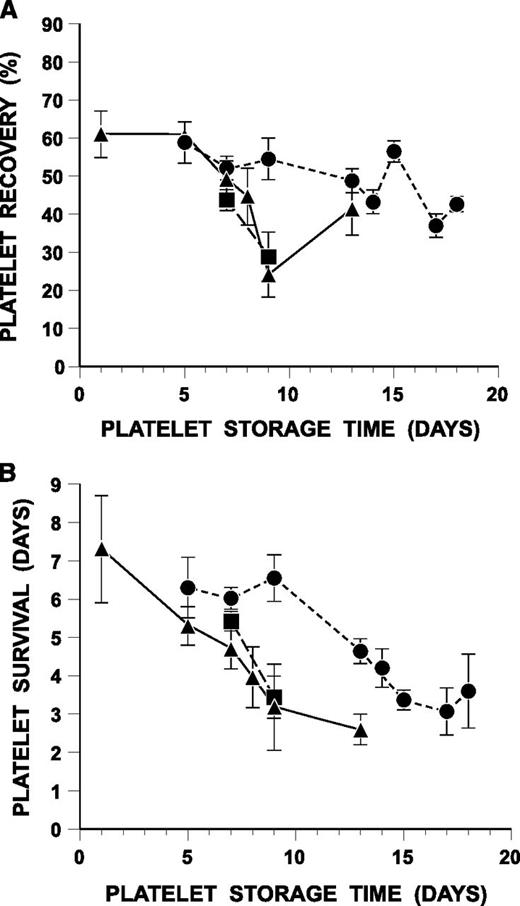

For Haemonetics platelets stored for 9, 13, and 14 days, comparisons were made to 1-day platelets and for 15-, 17- and 18-day storage to fresh platelets. For the Spectra data, no subjects had control platelets stored for either 1 day or fresh. For the Trima 7- and 9-day stored data, comparisons were made to fresh platelets. The data show that platelet recoveries met the FDA’s LCLs of ≥66% and ≥58% of control criteria for 7 days for Trima-stored platelets (Figure 2A-B). For Trima platelets stored for 9 days in Haemonetics CLX bags, the LCLs for recoveries were 67% and for survivals were 54%. At 13 days of storage, the LCLs for Haemonetics platelets were 65% for recoveries and 55% for survivals.

Stored platelet recoveries and survivals as a percentage of control platelets (fresh or 1-day plasma-stored platelets). (A) Stored platelet recoveries compared with control platelets. (B) Stored platelet survivals compared with control platelets. Shown are the 2-sided LCLs for the mean difference between the stored platelets and the proportion of the fresh or 1-day plasma platelets (control platelets) specified by the FDA criteria. The LCLs are a function of both the means and standard deviations of these differences. These limits have been transformed to a percent of control scale. The horizontal, dashed lines show the critical values specified by FDA’s poststorage platelet viability criteria; ie, platelet recoveries should be ≥66% and survivals ≥58% of each subject’s paired control platelets. ●, data for Haemonetics MCS+ platelets in CLX bags; ○, in CPP bags; ▪, for Trima platelets in Terumo BCT bags; and □, in Haemonetics CLX bags.

Stored platelet recoveries and survivals as a percentage of control platelets (fresh or 1-day plasma-stored platelets). (A) Stored platelet recoveries compared with control platelets. (B) Stored platelet survivals compared with control platelets. Shown are the 2-sided LCLs for the mean difference between the stored platelets and the proportion of the fresh or 1-day plasma platelets (control platelets) specified by the FDA criteria. The LCLs are a function of both the means and standard deviations of these differences. These limits have been transformed to a percent of control scale. The horizontal, dashed lines show the critical values specified by FDA’s poststorage platelet viability criteria; ie, platelet recoveries should be ≥66% and survivals ≥58% of each subject’s paired control platelets. ●, data for Haemonetics MCS+ platelets in CLX bags; ○, in CPP bags; ▪, for Trima platelets in Terumo BCT bags; and □, in Haemonetics CLX bags.

Effects of storage volume, platelet concentration, total platelets, and poststorage pCO2, pO2, and glucose on poststorage pH

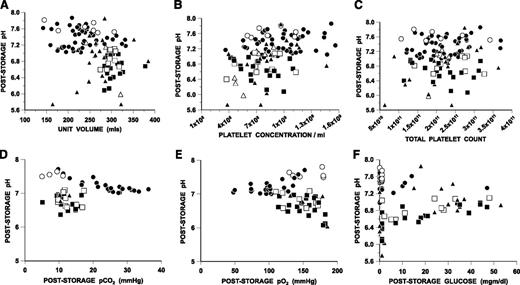

There were 12 Spectra or Trima platelets stored for 7 to 13 days in Terumo BCT bags that had poststorage pHs of ≤6.4. Ten of these units were transfused, and recoveries averaged 18 ± 16% and survivals averaged 1.8 ± 0.7 days (Table 1). In contrast, the lowest poststorage pH for Haemonetics platelets during ≤18 days of storage was 7.0. There was no apparent relationship between storage volume, platelet concentration, total platelet count, or poststorage pCO2 or pO2 values and poststorage pH (Figure 3A-E, respectively). All of the Terumo BCT platelets with low pHs had very low to absent residual glucose levels (Figure 3F). However, several other Terumo BCT and Haemonetics collections had similar low glucose levels with no effect on pH.

Relationship between poststorage pH and storage volume, platelet concentration, total platelet count, and poststorage pCO2, pO2, and glucose for Haemonetics, Spectra, or Trima collected platelets. (A) Poststorage pH vs storage volume. (B) Poststorage pH vs platelet concentration. (C) Poststorage pH vs total platelet count. (D) Poststorage pH vs poststorage pCO2. (E) Poststorage pH vs poststorage pO2. (F) Poststorage pH vs poststorage glucose concentration. ●, data for Haemonetics platelets in CLX bag; ○, in CPP bags; ▪, for Trima platelets in Terumo BCT bags; □, in Haemonetics CLX bags; ▲, for Spectra platelets in Terumo BCT bags; and △, in Haemonetics CLX bags.

Relationship between poststorage pH and storage volume, platelet concentration, total platelet count, and poststorage pCO2, pO2, and glucose for Haemonetics, Spectra, or Trima collected platelets. (A) Poststorage pH vs storage volume. (B) Poststorage pH vs platelet concentration. (C) Poststorage pH vs total platelet count. (D) Poststorage pH vs poststorage pCO2. (E) Poststorage pH vs poststorage pO2. (F) Poststorage pH vs poststorage glucose concentration. ●, data for Haemonetics platelets in CLX bag; ○, in CPP bags; ▪, for Trima platelets in Terumo BCT bags; □, in Haemonetics CLX bags; ▲, for Spectra platelets in Terumo BCT bags; and △, in Haemonetics CLX bags.

Comparisons of poststorage platelet recoveries and survivals to poststorage in vitro results

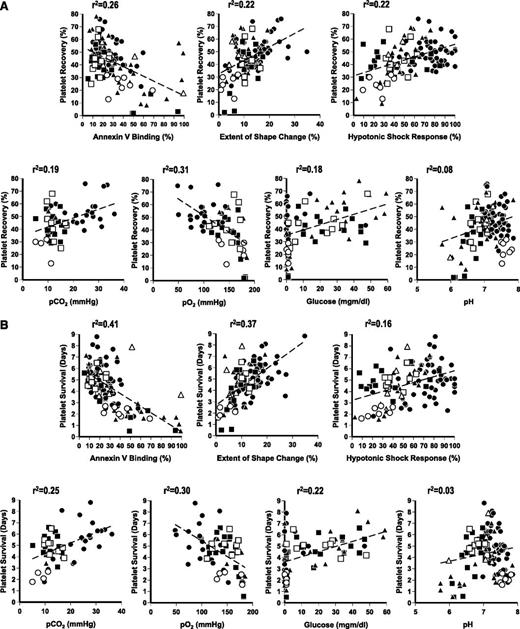

For both stored platelet recoveries and survivals, there are significant correlations with total platelet count of the product, storage volume, morphology score, glucose, Annexin V binding, ESC, HSR, pCO2, and pO2 (all P < .05) (Figure 4A-B).

Relationship between post-transfusion in vivo vs in vitro data. (A) Poststorage platelet recoveries vs in vitro measurements. (B) Poststorage platelet survivals vs in vitro measurements. ●, data for Haemonetics platelets in CLX bag; ○, in CPP bags; ▪, for Trima platelets in Terumo BCT bags; □, in Haemonetics CLX bags; ▲, for Spectra platelets in Terumo BCT bags; and △, in Haemonetics CLX bags. The regression lines for the data are shown as the hatched lines, and the r2 values are given on the figures.

Relationship between post-transfusion in vivo vs in vitro data. (A) Poststorage platelet recoveries vs in vitro measurements. (B) Poststorage platelet survivals vs in vitro measurements. ●, data for Haemonetics platelets in CLX bag; ○, in CPP bags; ▪, for Trima platelets in Terumo BCT bags; □, in Haemonetics CLX bags; ▲, for Spectra platelets in Terumo BCT bags; and △, in Haemonetics CLX bags. The regression lines for the data are shown as the hatched lines, and the r2 values are given on the figures.

Discussion

There is known to be a fair amount of heterogeneity in platelet recoveries and survivals among normal subjects.17 A recent study has further documented this heterogeneity, and, importantly, has demonstrated the reproducibility of fresh recoveries and survivals in the same subject.18 Murphy19 suggested that each subject serve as his/her own control by comparing their fresh platelet recoveries and survivals to their poststorage data, and the FDA has adopted this strategy for assessing poststorage platelet quality.6

We have previously evaluated plasma-stored Haemonetics or Spectra collected platelets for 5 to 8 days, and platelet recoveries and survivals were not significantly different between the 2 systems.20 With the plasma studies as background, we determined how long platelets could be stored in a PAS. Plasmalyte was selected as it was FDA licensed for intravenous use, it had previously been used for platelet storage, and no FDA-licensed PAS solutions were currently available.21-26 Unfortunately, many of our studies were completed before the FDA’s post-torage viability criteria were formulated, and therefore a variety of control platelets were used. Because there was little, if any, difference between 1-day stored and fresh platelet viabilities (Table 1), if either of these platelets were used as controls, FDA poststorage viability criteria were evaluated for the test PAS platelets.

As there were no differences in 7-day Haemonetics-stored platelet recoveries or survivals with PAS concentrations between 50% and 82%, we used a target PAS concentration of 80%. The Haemonetics platelets were close to meeting the FDA’s LCLs for platelet recoveries and survivals after storage for 13 days (Figure 2A-B). In sharp contrast to the plasma platelet storage studies where the Haemonetics and Spectra systems gave the same results, the Spectra PAS platelets had similar recoveries compared with Haemonetics, but survivals were significantly less (P = .05) after storage for only 7 days, and by 9 days, all the results were significantly less for the Spectra platelets (Table 3).

The discrepant results could be due to the different methods used to process the platelets for PAS storage; ie, hyperconcentration of the platelets with Spectra and resuspension in PAS vs platelet elutriation with PAS for the Haemonetics platelets. The hyperconcentration may have resulted in platelet damage, and therefore we evaluated the Trima system, which uses a different collection system and hyperconcentration method.8,12,13 Unfortunately, there were no differences in poststorage platelet viability regardless of the Terumo BCT system that was used (Tables 1 and 3; Figure 1A-B).

The next question was whether the storage bag made a difference. The Haemonetics CLX bag is composed of PVC plastic with tri-(2-ethylhexyl) trimillitate plasticizer. Haemonetics stopped manufacturing the CLX bags and, for 8 of the 11 15-day storage studies, a CPP bag composed of PVC plastic with a tributyl citrate plasticizer was used. Average recoveries for CLX vs CPP stored platelets were 56 ± 3% vs 24 ± 2% (P ≤ .001) and survivals were 3.7 ± 0.4 vs 2.2 ± 0.2 days (P = .004), respectively. Both the Terumo BCT systems use the same PVC bag with N-butyryl-tri-n-hexyl citrate plasticizer; ie, the same plasticizer as in the Haemonetics CPP bags. These data may suggest the plasticizer might have a substantial effect on poststorage platelet viability when platelets are stored in PAS but not in plasma. Certainly, red cell storage studies showed the di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate plasticizer helps maintain red cell viability during storage.27,28 In vitro platelet assays suggest that the storage bag29-32 and even the method of bag sterilization33 may affect platelet quality during storage. When Terumo BCT platelets were stored in Haemonetics CLX bags, there were clear improvements in poststorage platelet viability, but the results may still not be as good as Haemonetics platelets stored in Haemonetics CLX bags (Table 3).

Additional evidence that the storage bag could be a problem was the frequency with which pH values fell below acceptable levels during storage with the Terumo BCT but not with Haemonetics platelets (Tables 1 and 2). Twelve Terumo BCT collections had pH values of <6.4, and, of the 10 injected, platelet recoveries averaged 18 ± 16% and survivals averaged 1.8 ± 0.7 days (Table 1). In contrast, even though the Haemonetics platelets had higher cell counts because they were not leukoreduced compared with the in-process leukoreduced Terumo BCT platelets, all pHs were >7.0 for ≤18 days of storage. However, even when Haemonetics platelets were stored in CPP bags for 15 days, the lowest poststorage pH was 7.5, suggesting that the collection method plus the storage bag may be producing the low pH. There was no relationship between platelet volume, platelet concentration, total platelet count, or poststorage pCO2 or pO2 and poststorage pH, regardless of the storage conditions (Figure 3A-E). All of the Terumo BCT collections that had low pHs had low to absent residual glucose at the end of storage, whereas the residual glucose concentration did not appear to effect pH values for Haemonetics-collected platelets and for some of the Terumo BCT collections (Figure 3F). These data suggest that the Haemonetics bags allow the platelets to metabolize the acetate in the PAS to maintain pH better than platelets collected and stored in Terumo BCT bags. Studies by Murphy et al34 demonstrated that platelets metabolize 2 mM of acetate per day of storage. As PAS contains 27 mM of acetate, this suggests maintenance of platelet viability for ≥13 days of storage as our studies demonstrated. Some studies have suggested that enough plasma must be present during platelet storage to maintain glucose levels,35,36 whereas others have indicated that residual glucose is not required.37,38 Our studies have indicated that, depending on the storage conditions (mainly the storage bag), acetate can substitute for glucose to maintain platelet viability.

There were significant correlations between most of the in vitro assays and both platelet recoveries and survivals at the end of storage (all P < .05) (Figure 4A-B). Importantly, the Haemonetics CLX bags tended to have higher poststorage pCO2 values and lower pO2 values compared with platelets stored in the Haemonetics CPP or the Terumo BCT bags. These combined high pCO2 and low pO2 results correlated with both better platelet recoveries and survivals, suggesting the platelets were actively using O2 and releasing CO2 to maintain viability. The interactions between platelet metabolic parameters and poststorage platelet viability requires further explanation.

Several prior studies have evaluated the effects of various PAS compared with plasma using radiolabeled autologous platelet recovery and survival measurements with variable results.2,6,26,39-41 de Wildt-Eggen et al provided an excellent review of both in vitro and in vivo results of platelets stored in plasma or PAS.41 Only 2 prior studies have evaluated platelets stored in PAS beyond 7 days. At storage times of either 10 or 14 days, radiolabeled paired autologous platelet-rich plasma platelet concentrates were stored in a PAS or plasma, and PAS results were better than plasma.42 In the second study,21 11 stable thrombocytopenic patients were given 4- to 12-day PAS stored pooled buffy coat platelets, and the patients had good increments but shortened survivals.

There were several weaknesses in our studies. The studies were done sequentially and not randomized, the apheresis collections were done outside manufacturers’ guidelines, and Plasmalyte was used for elutriation of platelets on the Haemonetics system, and it is also not a licensed storage solution.6

Our data are the best results yet reported in the literature for extended stored platelets and demonstrate that platelet viability is better maintained in vitro than in vivo. Specifically, fresh radiolabeled autologous platelet survivals in the 38 normal subjects in our studies averaged 8.2 ± 0.2 days, whereas platelets could be stored in vitro for 13 days with a residual in vivo lifespan of 4.6 ± 0.3 for a combined in vitro/in vivo lifespan of almost 18 days, which is fully 9 days longer than in vivo (Table 1). This in vivo vs in vitro difference may be related to an ongoing work-related platelet utilization to maintain vascular integrity. Further studies are needed to confirm our results and to determine how to reduce any collection injury, identify the best PAS, identify the optimal PAS concentration, and identify the best storage bag. These parameters may all interact in ways we do not yet understand. We also recognize that either pathogen reduction or a sensitive and specific point of release bacterial assay will be needed before the FDA will license extended stored platelets.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the Haemonetics and Terumo BCT Corporations who supplied the collection systems and the Fenwal and Fresenius Corporations who supplied the Plasmalyte used in our studies. The authors acknowledge the excellent administrative support provided by Ginny Knight in the preparation of this manuscript.

This study was funded by a National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant (P50 HL081015).

Authorship

Contribution: S.J.S. designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; J.C. recruited normal subjects; M.K.J., T.C., E.P., and S.L.B. performed research and analyzed and interpreted data; and D.B. analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and designed figures and tables.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sherrill J. Slichter, Platelet Transfusion Research, Puget Sound Blood Center, 921 Terry Ave, Seattle, WA 98104-1256.; e-mail: sjslichter@psbc.org

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal