Key Points

Mutations in a conserved intronic enhancer element lead to GATA2 haploinsufficiency.

Mutations in GATA2, regardless of mutation type, lead to decreased GATA2 transcript levels and a common global transcriptional profile.

Previous reports of GATA2 mutations have focused on the coding region of the gene or full gene deletions. We recently identified 2 patients with novel insertion/deletion mutations predicted to result in mRNA nonsense-mediated decay, suggesting haploinsufficiency as the mechanism of GATA2 deficient disease. We therefore screened patients without identified exonic lesions for mutations within conserved noncoding and intronic regions. We discovered 1 patient with an intronic deletion mutation, 4 patients with point mutations within a conserved intronic element, and 3 patients with reduced or absent transcription from 1 allele. All mutations affected GATA2 transcription. Full-length cDNA analysis provided evidence for decreased expression of the mutant alleles. The intronic deletion and point mutations considerably reduced the enhancer activity of the intron 5 enhancer. Analysis of 512 immune system genes revealed similar expression profiles in all clinically affected patients and reduced GATA2 transcript levels. These mutations strongly support the haploinsufficient nature of GATA2 deficiency and identify transcriptional mechanisms and targets that lead to MonoMAC syndrome.

Introduction

GATA2 deficiency is characterized by monocytopenia; B, natural killer (NK), and dendritic cell lymphopenia; and mycobacterial, fungal, and viral infection.1,-3 It has been called both MonoMAC, for monocytopenia and Mycobacterium avium complex, and DCML deficiency, for dendritic cell, monocyte, B and NK lymphoid deficiency. Patients may present with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) or pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Unlike typical MDS, the marrow in patients with GATA2 deficiency is typically hypocellular and contains atypical and micro-megakaryocytes.4 Since GATA2 also plays a critical role in the development of the vascular and lymphatic systems,5 patients may present with lymphedema along with monosomy 7 and MDS, a triad known as Emberger syndrome.6,7

The GATA2 mutations reported previously cluster into 2 main groups. Mutations within the highly conserved C-terminal zinc finger include missense changes and deletions that result in loss of the C-terminus. They are predicted to allow production of a stable mRNA that is translated into an abnormal protein. In contrast, the other group of mutations includes full gene deletions, as well as frame shift or early stop mutations, predicted to cause nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of the mRNA, as reported in both MonoMAC and Emberger syndrome. However, several patients with clear MonoMAC phenotype lacked mutations within the GATA2 exonic sequence or large intragenic deletions. Of the 16 families reported by Vinh et al,1 mutations were only identified in 12.2 In view of the phenotypic homogeneity of the MonoMAC syndrome between our mutation-positive and mutation-negative families, we investigated whether distinct mechanisms explain GATA2 deficiency in patients lacking mutations.

Methods

Probands with clinical presentations consistent with MonoMAC syndrome and their family members gave informed consent on institutional review board-approved protocols at the National Institutes of Health between 1996 and 2012. Diseased controls were patients enrolled in the same approved protocols with similar infections but without MonoMAC phenotype and having wild-type GATA2. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

DNA and RNA were isolated from whole blood or isolated cells using Puregene DNA isolation kit (Qiagen) or RNeasy (Qiagen). Genomic amplification and sequencing were performed as described previously.2 cDNA amplification of GATA2 (NM_001145661.1) was performed using Superscript III One-Step RT-PCR with Hi Fidelity Platinum Taq kit (Life Technologies), 5% dimethylsulfoxide, and primers 196F 5′-GCGCCAGGGCGGCCGGAGGATG-3′ and 1963R 5′-GTGTCGGCCTTCGGGAAATGCTGGGCTGCTAAG-3′. Sequencing primers are available upon request.

Transient transfection analysis

The intron 5 enhancer reporter construct was constructed using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) fragment of the wild type or 28 base deletion intron 5 enhancer cloned upstream of the GATA2 isoform 2 exon 1 promoter in the pGl3 luciferase reporter plasmid (Promega). The C to T substitution in the E-twenty six (ETS) motif site was introduced by PCR-mediated mutagenesis, and all resulting constructs were sequence verified. Reporter plasmids were purified using the Purelink HQ miniprep kit (LifeTechnologies), and 2 independent plasmid preparations were used for each construct. Plasmids were introduced into K562 cells using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen). For each reporter construct, 2 × 105 cells were transfected with 500 ng of reporter plasmid and 50 ng control Renilla Luciferase. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cells were lysed in accordance with the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega), and the relative luciferase values were measured using the 20/20n luminometer (Turner Biosystems/Promega).

Cell sorting

Ficoll-separated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were stained with anti-CD3 (Becton Dickenson) and sorted on a FACS Aria (Becton Dickenson), collecting CD3+ and CD3− fractions. The granulocyte pellet from the Ficoll was treated with ACK lysis buffer (Lonza), washed, and lysed for RNA.

Relative allele expression

Chromatogram peaks from single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) identified by genomic sequence were measured using Pixelstick (PlumAmazing, Princeville, HI). The relative peak percentage was calculated as described8 using the peak height of 1 allele divided by the sum of the peak heights of both alleles. The relative genomic SNP peak height was compared with the same peak sequenced from full-length cDNA transcripts.

Gene expression panel

For the gene expression panel, 250 ng total RNA isolated from Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) transformed B-cell lines (RNeasy, Qiagen) was hybridized with reporter and capture probes for the nCounter GX Human Immunology kit (Nanostring Technologies) and/or a custom probe set according to manufacturer’s instructions, prepared on an nCounter Prep station and analyzed on an nCounter Analysis system. Data were normalized to spiked positive controls and housekeeping genes (nSolver Analysis system). Transcript counts less than the mean of the negative control transcripts plus 2 standard deviations for each sample were considered background on the human immunology panel; mean plus 1 standard deviation was considered background on the custom panel. Differences between sample groups were compared by 2-tailed Student t test with Welch approximation using MeV software.9,10

Results

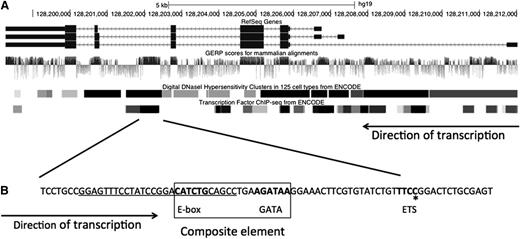

There are 3 known isoforms of GATA2 (Figure 1A) shown with the genomic evolutionary rate profile (GERP) score for each nucleotide, a measure of evolutionary constraint on each base. Regions with high GERP scores suggest putative functional elements.11,12 The GATA2 exons are highly conserved across species, as is the intron 5 region. The regions of intron 5 with high GERP scores have high DNaseI hypersensitivity scores as well as multiple occupied cis-elements demonstrated by ChIP-Seq (Figure 1B). Specifically, there is a composite cis-element, consisting of a Tal1/SCL-binding E-box motif, a spacer, and a GATA motif (WGATAA),13,,-16 followed by a conserved ETS motif.

Organization and conservation within the GATA2 locus. (A) GATA2 locus. The 3 identified isoforms of human GATA2 are shown with the associated GERP, DNaseI hypersensitive sites, and reported transcription factor binding sites.36,37 (B) The conserved region within intron 5 including the composite element encompassing an E-box and GATA motifs and the ETS motif. Bold text denotes motifs for transcription factor binding. Underline denotes deletion in patient 6.II.1; *recurrent ETS motif point mutation, c.1017+572C>T. Figure modified from UCSC browser.

Organization and conservation within the GATA2 locus. (A) GATA2 locus. The 3 identified isoforms of human GATA2 are shown with the associated GERP, DNaseI hypersensitive sites, and reported transcription factor binding sites.36,37 (B) The conserved region within intron 5 including the composite element encompassing an E-box and GATA motifs and the ETS motif. Bold text denotes motifs for transcription factor binding. Underline denotes deletion in patient 6.II.1; *recurrent ETS motif point mutation, c.1017+572C>T. Figure modified from UCSC browser.

We conducted genomic sequencing of phenotypically identified MonoMAC patients (Table 1) lacking recognized mutations and their at-risk family members. The proband of each family had cytopenias, infections, and MDS. Their presentations were indistinguishable from those of patients with null alleles reported previously.2 All exons (coding and noncoding) of GATA2 as well as conserved intronic regions from each proband were sequenced. We identified small frameshift mutations within exon 4, c.302delG and c.586_593dup, in patients 26.I.1 and 27.I.1, respectively (Table 1). These mutations were predicted to result in loss of expression of the mutant allele through NMD. Within the highly conserved region of intron 5 we identified a single point mutation in probands from 4 unrelated families. The mutation, c.1017+572C>T (i5C>T), is predicted to disrupt an ETS motif within intron 5 following the composite cis-element. Additionally, within the same region, 1 patient was identified with a 28 base deletion of intron 5 that eliminated the E-box and 5 bp of the spacer of the E-box/GATA composite element.17

Clinical features and GATA2 mutations identified in MonoMAC patients

| Pedigree No. . | Cytopenia . | Age* . | Infection . | MDS . | Mutation . | Mutation class . | Ref. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proband | |||||||

| 4.II.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 26 | CMV, MAC, recurrent pneumonias, histoplasmosis | MDS | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | 1 |

| 25.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 13 | HPV, Mycobacterium kansasii, MAC | MDS | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | |

| 11.II.1 | B/NK/mono | 9 | HPV, VZV, treatment-resistant Candida thrush and vaginitis | +Abnormal megakaryocytes | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | 1 |

| 28.I.1 | B/NK/mono | 21 | CMV pneumonia | +Abnormal megakaryocytes | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | |

| 6.II.1 | B/NK/mono | 22 | HPV, Group C Strep, M. tuberculosis | MDS | c.1017+512del28 | i5 | 1, 17 |

| 23.I.1† | T/B/NK | 21 | MAC | MDS | c.761C>T/unknown† | Unknown | 2 |

| 7.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 51 | HPV, M. kansasii | MDS | Unknown | Unknown | 1 |

| 29.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 45 | HPV | RAEB2 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 8.I.1 | B/NK/mono | 28 | HPV, MAC, Aspergillus | MDS | c.243_244delAinsGC | Haplo | 2 |

| 13.II.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 33 | HPV, MAC, histoplasmosis, Neosartorya udagawae | MDS | c.1-200_871+527 del 2033bp | Haplo | 1, 2, 7 |

| 20.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 13 | Molluscum contagiosum, HPV, MAC | MDS | c.769_778dup | Haplo | 2 |

| 22.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 25 | HPV, M. kansasii | MDS | c.941_951dup | Haplo | 2 |

| 26.I.1 | B | 15 | HSV, CMV | AML | c.302delG | Haplo | |

| 27.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 46 | HPV, M. kansasii | None | c.586_593dup | Haplo | |

| 41.I.1 | B/NK/mono | 9 | HSV | MDS | c.1009C>T; R337× | Haplo | |

| 2.II.3 | T/B/NK/mono | 36 | NTM, histoplasmosis | MDS | c.1192C>T; R398W | Mis | 1 |

| 5.II.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 19 | NTM | RAEB2 | c.1061C>T; T354M | Mis | 1 |

| 9.III.1 | B/NK/mono | 8 | Warts | MDS | c.1192C>T; R398W | Mis | 1 |

| 15.I.1 | B/NK/mono | 3 | NTM, HSV | MDS | c.1186C>T; R396W | Mis | 1,2 |

| 19.II.1 | B/NK/mono | 20 | NTM, EBV | None | c.1061C>T; T354M | Mis | 2 |

| 30.II.1 | B/NK/mono | 21 | NTM, HSV | None | c.1163T>C; M388T | Mis | |

| 37.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 32 | M. kansasii, MAC | MDS | c.1081C>T; R361C | Mis | |

| Family member | |||||||

| 4.II.5 | B/NK | 19 | HPV | MDS | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | 1 |

| 4.I.1 | Monocytosis | 78 | None | CMML | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | 1 |

| 4.III.2 | NK | 23 | None | None | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | |

| 4.III.3 | NK | 21 | None | None | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | |

| 6.I.1 | ND | 13 | Lymphedema | ND | c.1017+512del28 | i5 | |

| 6.III.2 | None | 1.5 | None | ND | c.1017+512del28 | i5 | |

| 33.II.1 | Thrombo | 50 | None | ND | c.1-276T>G‡ | Unknown | |

| 13.I.2 | T/B/NK/mono | 61 | HPV, lymphedema | +Abnormal megakaryocytes | c.1-200_871+527 del 2033bp | Haplo | 1, 2, 7 |

| 1.II.5 | T/B/NK/mono | 49 | NTM, HPV | CMML | c.1192C>T; R398W | Mis | 1 |

| 30.I.1 | ND | 65 | None | None | c.1163T>C; p.M388T | Mis | |

| 33.III.3 | Mono | 9 | None | ND | c.1099insG; D367fs c.1-276T>G‡ | Mis | |

| 40.I.1 | B | 54 | None | None | c.1187G>A; R396Q | Mis |

| Pedigree No. . | Cytopenia . | Age* . | Infection . | MDS . | Mutation . | Mutation class . | Ref. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proband | |||||||

| 4.II.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 26 | CMV, MAC, recurrent pneumonias, histoplasmosis | MDS | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | 1 |

| 25.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 13 | HPV, Mycobacterium kansasii, MAC | MDS | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | |

| 11.II.1 | B/NK/mono | 9 | HPV, VZV, treatment-resistant Candida thrush and vaginitis | +Abnormal megakaryocytes | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | 1 |

| 28.I.1 | B/NK/mono | 21 | CMV pneumonia | +Abnormal megakaryocytes | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | |

| 6.II.1 | B/NK/mono | 22 | HPV, Group C Strep, M. tuberculosis | MDS | c.1017+512del28 | i5 | 1, 17 |

| 23.I.1† | T/B/NK | 21 | MAC | MDS | c.761C>T/unknown† | Unknown | 2 |

| 7.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 51 | HPV, M. kansasii | MDS | Unknown | Unknown | 1 |

| 29.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 45 | HPV | RAEB2 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 8.I.1 | B/NK/mono | 28 | HPV, MAC, Aspergillus | MDS | c.243_244delAinsGC | Haplo | 2 |

| 13.II.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 33 | HPV, MAC, histoplasmosis, Neosartorya udagawae | MDS | c.1-200_871+527 del 2033bp | Haplo | 1, 2, 7 |

| 20.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 13 | Molluscum contagiosum, HPV, MAC | MDS | c.769_778dup | Haplo | 2 |

| 22.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 25 | HPV, M. kansasii | MDS | c.941_951dup | Haplo | 2 |

| 26.I.1 | B | 15 | HSV, CMV | AML | c.302delG | Haplo | |

| 27.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 46 | HPV, M. kansasii | None | c.586_593dup | Haplo | |

| 41.I.1 | B/NK/mono | 9 | HSV | MDS | c.1009C>T; R337× | Haplo | |

| 2.II.3 | T/B/NK/mono | 36 | NTM, histoplasmosis | MDS | c.1192C>T; R398W | Mis | 1 |

| 5.II.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 19 | NTM | RAEB2 | c.1061C>T; T354M | Mis | 1 |

| 9.III.1 | B/NK/mono | 8 | Warts | MDS | c.1192C>T; R398W | Mis | 1 |

| 15.I.1 | B/NK/mono | 3 | NTM, HSV | MDS | c.1186C>T; R396W | Mis | 1,2 |

| 19.II.1 | B/NK/mono | 20 | NTM, EBV | None | c.1061C>T; T354M | Mis | 2 |

| 30.II.1 | B/NK/mono | 21 | NTM, HSV | None | c.1163T>C; M388T | Mis | |

| 37.I.1 | T/B/NK/mono | 32 | M. kansasii, MAC | MDS | c.1081C>T; R361C | Mis | |

| Family member | |||||||

| 4.II.5 | B/NK | 19 | HPV | MDS | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | 1 |

| 4.I.1 | Monocytosis | 78 | None | CMML | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | 1 |

| 4.III.2 | NK | 23 | None | None | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | |

| 4.III.3 | NK | 21 | None | None | c.1017+572C>T | i5 | |

| 6.I.1 | ND | 13 | Lymphedema | ND | c.1017+512del28 | i5 | |

| 6.III.2 | None | 1.5 | None | ND | c.1017+512del28 | i5 | |

| 33.II.1 | Thrombo | 50 | None | ND | c.1-276T>G‡ | Unknown | |

| 13.I.2 | T/B/NK/mono | 61 | HPV, lymphedema | +Abnormal megakaryocytes | c.1-200_871+527 del 2033bp | Haplo | 1, 2, 7 |

| 1.II.5 | T/B/NK/mono | 49 | NTM, HPV | CMML | c.1192C>T; R398W | Mis | 1 |

| 30.I.1 | ND | 65 | None | None | c.1163T>C; p.M388T | Mis | |

| 33.III.3 | Mono | 9 | None | ND | c.1099insG; D367fs c.1-276T>G‡ | Mis | |

| 40.I.1 | B | 54 | None | None | c.1187G>A; R396Q | Mis |

Abbreviations: CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; CMV, cytomegalovirus; Haplo, haploinsufficiency; HPV, human papillomavirus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; i5, intron 5 mutation; Mis, missense mutation.

Approximate age (y) at presentation or age at diagnosis if initial presentation unknown.

Previously reported as missense mutation; however, functional studies have demonstrated loss of expression of 1 allele.

Change in 5′ UTR of undetermined significance.

At-risk family members were subsequently screened for the presence of the mutations found in the probands. We identified 6 additional individuals with intron 5 mutations. Four individuals from family 4 had i5C>T point mutations: the father (4.I.1), sister (4.II.5), and 2 adult children (4.III.2, 4.III.3). The father (6.I.1) of the proband in family 6 as well as the proband’s 18-month-old son (6.III.2) were heterozygous for the 28 base deletion spanning the start of the E-box/GATA composite element. Onset and phenotype varied between mutation-positive family members, ranging from full MonoMAC phenotype (4.II.5), to monocytosis and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia at age 78 years without previous infection history (4.I.1), to isolated reduced NK cell numbers (4.III.2, 4.III.3). Patient 6.III.2 had normal monocyte and lymphocyte counts and percentages but mildly reduced neutrophils. Only 2 relatives in the cohort, 6.I.1 and 13.I.2, displayed lymphedema. The mutation in the 8 patients with i5C>T disrupts an ETS motif (Figure 1, asterisk), while the mutation in the patient with the 28 bp deletion eliminates the E-box and 5 bp of the spacer from the composite element (Figure 1, underlined).

Earlier studies in mice demonstrated that the intronic region spanning the composite element (referred to as the +9.5 enhancer element) is sufficient to drive reporter gene expression in fetal liver and vascular endothelium in transgenic mice.13 Both the E-box and GATA motif were necessary for the enhancer activity of the +9.5 element,13,14 whereas the requirement for the ETS motif was not addressed. We tested whether the ETS motif mutation or 28 base deletion influenced the GATA factor-dependent enhancer activity in the human intron 5 enhancer element. Luciferase vector constructs containing the wild-type human intron 5 enhancer, the 28 base deletion, or the C>T substitution in the ETS motif coupled to the untranslated first exon of GATA2 (NM_032638) were transfected into K562 cells that express endogenous GATA2 (Figure 2). With the wild-type enhancer construct set as 100% luciferase activity, both the i5C>T mutated enhancer and the 28 base deletion had significantly lower activity (P < .001). Therefore, the ETS motif site and the E-box-GATA composite element are both required in cis to maximize the activity of the intron 5 enhancer.

Mutation of conserved ETS motif or deletion of the composite element reduces intron 5 enhancer activity. Luciferase activity from exon 1 preceded by the wild-type intron 5 enhancer set and exon 1 preceded by the intron 5 enhancer containing either the 28 base deletion seen in patient 6.II.1 or the ETS motif C>T point mutation seen in patients 4.II.1, 11.II.1, 25.I.1, and 28.I.1. ***P < .001.

Mutation of conserved ETS motif or deletion of the composite element reduces intron 5 enhancer activity. Luciferase activity from exon 1 preceded by the wild-type intron 5 enhancer set and exon 1 preceded by the intron 5 enhancer containing either the 28 base deletion seen in patient 6.II.1 or the ETS motif C>T point mutation seen in patients 4.II.1, 11.II.1, 25.I.1, and 28.I.1. ***P < .001.

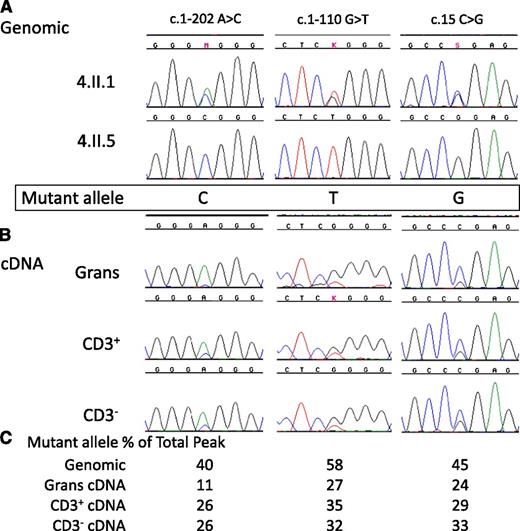

To test whether the i5C>T mutation influences transcription, we sequenced genomic DNA as well as cDNA from sorted PBMCs in patient 4.II.1. Due to the lack of B, NK, and monocyte cells in peripheral blood, we separated CD3+ cells from CD3− cells and also analyzed the cells within the granulocyte pellet. Patient 4.II.1 is heterozygous by genomic sequence at several known SNPs within the GATA2 cDNA, while her sister, 4.II.5, who also carries the i5C>T mutation, is homozygous at the same SNPs (Figure 3A). This homozygosity allowed us to determine the phase of mutation with cDNA SNPs and thereby permitted evaluation of relative allele expression. The mutation in this family resides on the CTG haplotype allele. Sequencing of full length GATA2 cDNA in 4.II.1 demonstrated reduced levels of the mutation-bearing CTG haplotype allele compared with her wild-type allele (Figure 3B). In the genomic sequence, the heterozygous peak heights were similar, whereas in the cDNA sequence, the CTG allele accounted for roughly one third of the total peak height compared with the wild-type AGC allele seen in both CD3+ and CD3− cells as well as granulocytes.

Reduced expression of mutant allele in a patient with c.1017+572C>T. (A) Genomic sequences of GATA2 exons in patient 4.II.1 and her sister 4.II.5 indicate the phase of the SNPs and the mutation. M, K, and S refer to base calls of mixed nucleotide bases at a single site, A/C, G/T, and C/G, respectively. (B) GATA2 cDNA sequences from isolated granulocytes (Grans), CD3+ T-cells (CD3+), and CD3– PBMCs (CD3–) demonstrate reduced expression of c.1017+572C>T allele. (C) Quantitation of relative peak heights of patient 4.II.1 mutant allele as a percentage of the combined peak height at that site.

Reduced expression of mutant allele in a patient with c.1017+572C>T. (A) Genomic sequences of GATA2 exons in patient 4.II.1 and her sister 4.II.5 indicate the phase of the SNPs and the mutation. M, K, and S refer to base calls of mixed nucleotide bases at a single site, A/C, G/T, and C/G, respectively. (B) GATA2 cDNA sequences from isolated granulocytes (Grans), CD3+ T-cells (CD3+), and CD3– PBMCs (CD3–) demonstrate reduced expression of c.1017+572C>T allele. (C) Quantitation of relative peak heights of patient 4.II.1 mutant allele as a percentage of the combined peak height at that site.

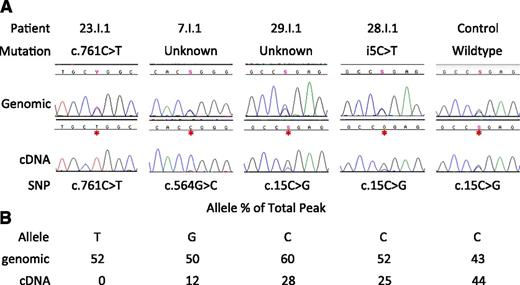

Patients with intron 5 mutations and those with known GATA2 mutations that should cause NMD had reduced GATA2 allelic expression. Based on these observations, we pursued reduced allelic expression of GATA2 as the basis for other phenotypic MonoMAC patients. Three patients, 23.I.1 (c.761C>T causing P254L nonsynonymous change, patient 23 from Hsu et al2 ) and 2 without identified mutations in GATA2 exons or conserved intronic or promoter regions, 7.I.1 and 29.I.1 (patient 7 from Vinh et al1 and unpublished, respectively), all had significantly reduced expression of 1 allele by cDNA analysis, similar to the allelic expression of patients with the i5C>T mutation (Figure 4). While the P254L change is predicted by PolyPhenII18 to be deleterious, cDNA sequence shows expression of only the c.761T transcript, suggesting that this patient also carries a mutation on the other allele, leading to haploinsufficiency, and only expresses GATA2 mRNA from the P254L allele. The function of the P254L protein is unclear; however, expression from a single allele is insufficient for long-term normal hematopoiesis19,20 and leads to the MonoMAC syndrome in humans2,6 and abnormal bone marrow repopulation in mouse models.19

Reduced allelic expression of GATA2 in MonoMAC patients. (A) Genomic vs cDNA GATA2 sequence for patients 23.I.1, 7.I.1, 29.I.1, 28.I.1, and a healthy control. Shown is a portion of the transcript in which the patient is heterozygous at the genomic level with reduced or absent expression of 1 allele by full-length cDNA sequence. Y, S refer to base calls of mixed nucleotide bases at a single site, C/T and C/G, respectively. (B) Quantitation of relative peak heights of patient’s mutant allele as a percentage of the combined peak height at that site.

Reduced allelic expression of GATA2 in MonoMAC patients. (A) Genomic vs cDNA GATA2 sequence for patients 23.I.1, 7.I.1, 29.I.1, 28.I.1, and a healthy control. Shown is a portion of the transcript in which the patient is heterozygous at the genomic level with reduced or absent expression of 1 allele by full-length cDNA sequence. Y, S refer to base calls of mixed nucleotide bases at a single site, C/T and C/G, respectively. (B) Quantitation of relative peak heights of patient’s mutant allele as a percentage of the combined peak height at that site.

Using chromatogram peak height measurements, patient 7.I.1 had equal quantities of the G and C alleles at c.564 in the genomic sequence. However, when full-length cDNA was examined, the G allele represented only 12% of the total peak height, indicating loss of expression of that allele. Likewise, patient 29.I.1 exhibited similar allele peak heights by genomic sequence, while 1 allele was present at only 28% of the total peak by cDNA. This is similar to patient 28.I.1 with i5C>T mutation, and only 25% of the total peak is from the mutant allele and in contrast to a healthy normal with even allele ratios in both genomic and cDNA sequence. Thus, in patients with the MonoMAC phenotype lacking an identified mutation, uniallelic cDNA expression provided further evidence for GATA2 haploinsufficiency.

We screened an additional 15 patients with informative SNPs and available EBV lines. All informative patients and family members with mutations in the intronic enhancer region demonstrated skewed allelic expression, including the previously reported patient with the 28 base deletion of the intron 5 composite element,17 as did a patient with a premature termination predicted to result in NMD. We screened 6 patients and 2 family members with known missense changes, 6 of whom (5.I.1, 15.I.1, 19.II.1, 30.I.1, 30.II.1, 37.I.1) demonstrated equal representation of both alleles, while 2 (2.II.3 and 40.I.1) had skewed allelic expression at a level similar to that of the intron 5 patients. Three individuals with wild-type GATA2 had equal representation of both alleles (data not shown).

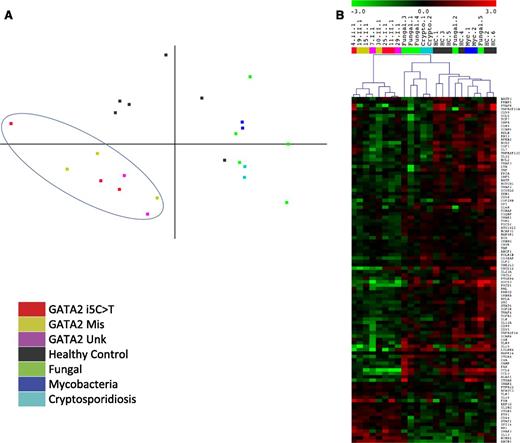

We tested whether the i5C>T point mutations were transcriptionally equivalent to identified missense GATA2 mutations. We used the Nanostring Human Immunology Panel to quantitate expression of 512 immune system genes and 15 housekeeping genes. We used EBV-transformed B-cell lines from patients and healthy normals as the source of RNA since they provide a renewable, homogeneous cell population without the inherent differences in lymphocyte and monocyte subsets in patient PBMCs. Additionally, acute events in patients that can drive transcriptional profiles, such as infections and neoplasms, probably do not differentially affect EBV lines. No significant differences in mRNA transcript expression between the missense and i5C>T mutated EBV-B cells were apparent. Principal component analysis of the full dataset separates GATA2 patients from both healthy normals as well as diseased controls, showing distinct clustering of their transcript profiles (Figure 5A). Samples from healthy normal controls are clearly different from the phenotypic MonoMAC patients, including the 2 MonoMAC patients lacking recognized mutations who had reduced cDNA expression from 1 GATA2 allele. This clustering is not simply due to the patients having a defect in an immune gene per se, since disease control samples with similar infections—disseminated mycobacteria, fungi, or cryptosporidia—yet wild-type GATA2 sequence, clustered separately from both GATA2 patients and normal controls.

GATA2 patients have unique transcript profiles compared with healthy normals and diseased controls. Normalized transcript counts from nCounter analysis used for (A) 2-dimensional principal component analysis of patients with GATA2 i5C>T (patients 4.II.1, 11.II.1, 25.I.1), missense mutation (GATA2 Mis; patients 15.I.1, 19.II.1, 30.II.1), and reduced allelic expression without identified GATA2 mutation (GATA2 Unk; patients 7.I.1, 29.I.1) compared with healthy controls and diseased controls with similar infection types but wild-type GATA2. Fungal, disseminated coccidioidomycosis or histoplasmosis; Mycobacteria, disseminated mycobacteria; Cryptosporidiosis, disseminated cryptosporidium. (B) Hierarchical clustering of transcripts differentially regulated (P < .05) between healthy normals and GATA2 mutated patients irrespective of genotype. Samples and color labels correspond to mutations as in A.

GATA2 patients have unique transcript profiles compared with healthy normals and diseased controls. Normalized transcript counts from nCounter analysis used for (A) 2-dimensional principal component analysis of patients with GATA2 i5C>T (patients 4.II.1, 11.II.1, 25.I.1), missense mutation (GATA2 Mis; patients 15.I.1, 19.II.1, 30.II.1), and reduced allelic expression without identified GATA2 mutation (GATA2 Unk; patients 7.I.1, 29.I.1) compared with healthy controls and diseased controls with similar infection types but wild-type GATA2. Fungal, disseminated coccidioidomycosis or histoplasmosis; Mycobacteria, disseminated mycobacteria; Cryptosporidiosis, disseminated cryptosporidium. (B) Hierarchical clustering of transcripts differentially regulated (P < .05) between healthy normals and GATA2 mutated patients irrespective of genotype. Samples and color labels correspond to mutations as in A.

Given the clustering among MonoMAC patients regardless of specific genotype, we compared transcript levels in healthy normals and those affected. We found significant (P < .05) differences in expression levels of 102 genes (Figure 5B): 18 had increased expression and 84 decreased expression (supplemental Table 1). Genes with altered expression include FYN, RUNX1, and ETS1 transcription factors (increased) and CXCL12, SRC, and NOTCH1 (decreased). Using Ingenuity IPA core analysis, the subset of differentially expressed genes was analyzed in terms of systems, diseases, and disorders as well as molecular and cellular processes (supplemental Table 2).

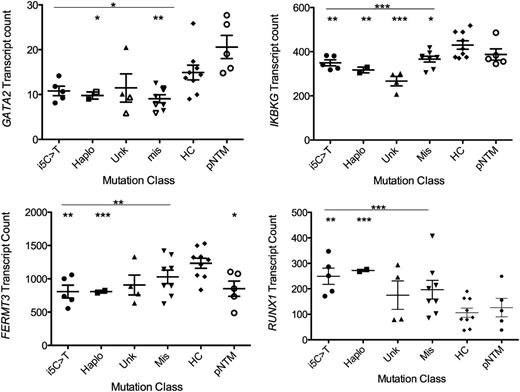

We then designed a custom Nanostring code set to directly query GATA2 transcript levels. The MonoMAC patients, regardless of mutation type, had decreased GATA2 transcript levels compared with healthy controls and pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial patients with wild-type GATA2 (68%, P = .0218 and 49%, P = .0177, respectively). Both the haplo and missense groups were significantly decreased compared with healthy controls (P = .0220, 0.0083, respectively), while transcript levels between mutation types were not significant (Figure 6). We examined several genes with significantly altered transcript levels between patients and controls and found conserved GATA2 binding sites with demonstrated GATA2 chromatin occupancy localized near the gene (supplemental Figures 1 and 2). While GATA2, IKBKG, and FERMT3 have decreased transcript levels in GATA2 patients, RUNX1 transcript counts were elevated in the patients (Figure 6). Reduced levels of Fermt3 have been found in PECAM1+ embryonic cells in mice with either homozygous or heterozygous deletion of the +9.5 intronic element.17

Transcript counts of GATA2, IKBKG, FERMT3, and RUNX1 from patients segregated by mutation class. i5C>T (n = 5, patients 4.II.1, 4.II.5, 6.II.1, 11.I.1, 25.I.1); Haplo, identified mutations resulting in loss of expression of 1 allele (n = 2, patients 13.I.2, 41.I.1); Unk, patients without identified pathogenic mutations (n = 4, patients 7.I.1, 23.I.3, 29.I.1, 33.II.2); Mis, identified GATA2 mutations predicted to result in a single amino acid change or a late frameshift with demonstrated mRNA stability (n = 8, patients 1.II.5, 5.I.1, 9.II.1, 15.I.1, 30.II.1, 33.III.3, 37.I.1, 40.I.1); compared with healthy controls (HC) (n = 9) or patients with pNTM (n = 5) with wild-type GATA2. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Transcript counts of GATA2, IKBKG, FERMT3, and RUNX1 from patients segregated by mutation class. i5C>T (n = 5, patients 4.II.1, 4.II.5, 6.II.1, 11.I.1, 25.I.1); Haplo, identified mutations resulting in loss of expression of 1 allele (n = 2, patients 13.I.2, 41.I.1); Unk, patients without identified pathogenic mutations (n = 4, patients 7.I.1, 23.I.3, 29.I.1, 33.II.2); Mis, identified GATA2 mutations predicted to result in a single amino acid change or a late frameshift with demonstrated mRNA stability (n = 8, patients 1.II.5, 5.I.1, 9.II.1, 15.I.1, 30.II.1, 33.III.3, 37.I.1, 40.I.1); compared with healthy controls (HC) (n = 9) or patients with pNTM (n = 5) with wild-type GATA2. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Discussion

One third of previously reported patients with defects in GATA2 have mutations predicted to cause loss of protein from the mutant allele, either through small insertions/deletions that result in nonsense-mediated decay2,3,6 or through intragenic2 or full gene deletions.7 These patients are predicted to have reduced GATA2 levels, which lead to clinical disease and constitute haploinsufficiency. Heterozygous knockout mice with reduced endogenous levels of Gata2 are born at normal Mendelian ratios but exhibit an approximately 50% reduction in the number of adult bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs); those Gata2+/− HSCs have reduced repopulating potential.19,20 We therefore predicted that patients with mutations resulting in significantly reduced expression from 1 allele would mimic previously characterized heterozygous GATA2 missense mutations.2,3,6,21

The intron 5 mutations we identified reside within a region conserved since Xenopus (divergence ∼350 million years ago22 ), a criterion that can imply functional importance. GATA2 does not act independently, rather there are several cooperating transcription factors that occupy closely linked chromatin locations.23 In mice, Gata2, stem cell leukemia protein/T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia protein (Scl/TAL1), and the ETS family member, Fli1, form a core recursive network,24 and multiple factors, including GATA2, FLI1, and Scl/TAL1, occupy endogenous chromatin sites.14,25,-27 Mutations of the murine +9.5 kb site E-box, spacer, or GATA motif strongly reduce the enhancer activity of the composite element in cultured erythroid precursor cells expressing endogenous Gata2.13 Furthermore, transgenic analysis provided evidence that the +9.5 kb site enhancer is active in the endothelium and fetal liver of developing mouse embryos.14,16 Importantly, targeted deletion of the endogenous +9.5 kb site revealed its crucial role in the genesis of fetal liver HSCs and for conferring Gata2 expression in fetal liver and embryonic PECAM1+ cells.17 It is interesting to note that +9.5−/− embryos died between E13.5 and E14.5 of development and were characterized by ablation of long-term repopulating HSCs and progenitors in the fetal liver and severe hemorrhaging. The heterozygous mutation of the +9.5 site also reduced HSC numbers, long-term repopulating activity, and Gata2 expression, but +9.5+/− embryos were born in Mendelian ratios.17

The mutations we identified in the intron 5 region occur at a LIM domain binding protein 1 (Ldb1) complex binding site, similar to others present in a high percentage of genes critical for HSC maintenance.28,29 Examining a compendium of mouse ChIP-Seq data, the intron 5 region is occupied by multiple components of the GATA2-Scl/TAL1-FLI1 complex, including LIM domain only 2 (Lmo2), Gata2, Fli1, and Scl30 as well as Ldb1.28 Based on the disruption of the composite element in 1 patient and the ETS motif mutations, which occur at a consensus FLI1 binding site31 adjacent to the composite element, it is possible that these mutations disrupt the assembly and/or function of the Scl/TAL1-GATA-2, FLI1 multimeric complex, providing a mechanism that underlies these patients’ GATA2 haploinsufficiency. Mathematical modeling indicates tightly controlled protein levels32 supported by <30-minute half-life of GATA2.33 Given the established concentration-dependent actions of Gata2 in mice,19,20 relatively modest decreases in the total level of Gata2 are likely to translate into significant molecular and cellular deficits. As well, the heterozygous +9.5 mutation in mice caused defects in Gata2 target gene expression.

We identified several genes with differential transcription patterns in GATA2 mutant cell lines. While several of the genes, including RUNX1, NOTCH1, ETS1, and IKBKG, have GATA2 binding sites within the gene region, GATA2 is classified as a remote element preferential transcription factor and commonly occupies chromatin in nonpromoter regions that can be intronic or large distances (>20 kb) away.15,34,35

Of the original 16 patients with MonoMAC syndrome described by Vinh et al,1 12 had identified GATA2 mutations.2 We have demonstrated that the 4 probands not previously associated with exonic GATA2 mutations have GATA2 haploinsufficiency due either to intron 5 mutations or reduced expression of 1 GATA2 allele. As would be predicted, analysis of GATA2 transcript levels has shown that mutations causing loss of expression of 1 allele result in reduced GATA2 transcript level. Likewise, mutations predicted to result in a nonfunctional protein also result in reduced levels of GATA2 transcripts. The consistency of the large-scale transcript expression data across mutation types demonstrates that haploinsufficiency at the transcript level results in similar alterations of target genes when compared with patients with missense mutations. Given the reduced GATA2 transcript levels, similar transcriptional profile of immune-related genes, and comparable clinical presentation of probands, regardless of mutation type, we propose that GATA2 deficiency is a disease of haploinsufficiency, whether by loss of production of protein at the transcript level or production of a nonfunctional protein that fails to drive transcription of the GATA2 gene.

We identified 11 patients from 5 unrelated families with mutations disrupting critical functional units in intron 5, as well as 3 patients with significant loss of expression from 1 GATA2 allele, all yielding similar clinical phenotypes, GATA2 transcript levels, and global transcriptional profiles. Reduced expression of GATA2 is a common underlying cause of the syndromes variously known as MonoMAC, DCML, and Emberger and is due to various defects in the coding and noncoding regions of the gene.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and by a grant from National Institutes of Health (DK68634) to E.H.B.

Authorship

Contribution: A.P.H. and K.D.J. designed and performed experiments; A.P.H., K.D.J., E.L.F., and J.E.L. analyzed data; E.L.F. and R.S. created the human intron 5 enhancer and murine +9.5 constructs, respectively; L.S. collected patient clinical data; J.C.-R., D.D.H., C.S.Z., and S.M.H. provided clinical care and patient samples; A.P.H, wrote the manuscript; and K.D.J., E.H.B., J.C.-R., and S.M.H revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Steven M. Holland, CRC B3-4141, MSC 1684, Bethesda, MD 20892-1684; e-mail: smh@nih.gov.

References

Author notes

A.P.H. and K.D.J. contributed equally to this study.