Key Points

PKR may be an unrecognized but important regulator of HSPC cell fate.

PKR expression regulates the frequency of HSPCs in the bone marrow and their response to stress.

Abstract

Protein kinase R (PKR) is an interferon (IFN)-inducible, double-stranded RNA-activated kinase that initiates apoptosis in response to cellular stress. To determine the role of PKR in hematopoiesis, we developed transgenic mouse models that express either human PKR (TgPKR) or a dominant-negative PKR (TgDNPKR) mutant specifically in hematopoietic tissues. Significantly, peripheral blood counts from TgPKR mice decrease with age in association with dysplastic marrow changes. TgPKR mice have reduced colony-forming capacity and the colonies also are more sensitive to hematopoietic stresses. Furthermore, TgPKR mice have fewer hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs), and the percentage of quiescent (G0) HSPCs is increased. Importantly, treatment of TgPKR bone marrow (BM) with a PKR inhibitor specifically rescues sensitivity to growth factor deprivation. In contrast, marrow from PKR knockout (PKRKO) mice has increased potential for colony formation and HSPCs are more actively proliferating and resistant to stress. Significantly, TgPKR HSPCs have increased expression of p21 and IFN regulatory factor, whereas cells from PKRKO mice display mechanisms indicative of proliferation such as reduced eukaryotic initiation factor 2α phosphorylation, increased extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2 phosphorylation, and increased CDK2 expression. Collectively, data reveal that PKR is an unrecognized but important regulator of HSPC cell fate and may play a role in the pathogenesis of BM failure.

Introduction

Multiple interactions between cytokines and growth factors with hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) determine whether and how these cells remain viable to undergo self-renewal or commit to differentiation into specific lineages of mature blood cells in response to stress.1-5 The interferon (IFN)-inducible, double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase, protein kinase R (PKR), is a sentinel stress kinase that initiates the response to diverse cellular challenges such as viral infection, hematopoietic growth factor deprivation, inflammatory cytokines, Toll-like receptor ligands, and chemoradiation therapy.6-8 We and others have reported that activated PKR can regulate proliferation and apoptosis by phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) to inhibit new protein synthesis, activation of a PP2A-dependent Bcl2 dephosphorylation mechanism resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction, and activation of signaling pathways such as nuclear factor κB, p53, and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1.6,9-12 Significantly, loss of the PKR expression/activity has been associated with increased growth of human breast carcinoma, nonsmall cell lung cancer, B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, suggesting that the loss of PKR activity may contribute to increased growth and malignancy.13-16

In contrast, increased PKR activity may inhibit cell growth and enhance stress responses, leading to apoptosis. In support of this notion, activated PKR has been reported to be increased in myeloid progenitor (CD34+CD33+) cells in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and inhibition of PKR expression or activity can partially reverse the suppressive effects of IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) cytokines on hematopoietic colony formation by normal or MDS-derived CD34+ cells.17,18 Taken together, these results suggest that PKR may have a negative regulatory role in hematopoiesis and potentially play a role in bone marrow (BM) failure states.

To test the role of PKR in the regulation of HSPC self-renewal, differentiation, and in response to stress, we constructed novel transgenic mice that express either human PKR (TgPKR) or a catalytically null/dominant-negative PKR mutant (TgDNPKR) specifically in hematopoietic cells to compare hematopoiesis in these mice with wild-type (WT)- or PKR-null mice. TgPKR mice demonstrate a much reduced frequency of HSPCs that display decreased proliferation, reduced hematopoietic colony formation, and increased sensitivity to apoptosis-inducing cell stress. Interestingly, we have discovered that PKR knockout (PKRKO) mice have increased numbers of HSPCs. In addition, PKRKO cells have increased colony-forming unit (CFU) activity and are more resistant to cell death. These data indicate that PKR is an unrecognized but necessary negative regulator of HSPC fate and may play a role in BM failure states.

Materials and methods

Generation of human TgPKR and TgDNPKR mice

The cDNAs encoding either the TgPKR or the TgDNPKR (K296R) mutant were amplified and ligated into pcr2.1 by the use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers that inserted a 5′ SfiI site and a 3′ NotI site (Invitrogen). The PKR or DNPKR open reading frame was ligated as a SfiI to NotI fragment into the HS21/45-vav expression vector (provided by Jerry M. Adams, WEHI, Melbourne, Australia) to generate vav-PKR or vav-DNPKR expression vectors. The University of Florida DNA sequencing core confirmed vector sequences, and expression of TgPKR or DNPKR from the vav vector was tested for expression in FDC-P1 cells. After HindIII digestion to remove the plasmid backbone, vav-PKR or vav-DNPKR was microinjected into pronuclei of C57BL/6 eggs by the University of Florida transgenic mouse core facility. Founder transgenic mice were identified by PCR with the forward primer: 5′-TGTGCATCGGGGGTGCATGG-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-TCACGCTCCGCCTTCTCGTT-3′, which generates a 510-bp product. Founder mice were crossed with C57BL/6 mice to generate transgenic lines. Transgene-negative siblings were used as WT controls throughout the study. In addition, PKRKO mice were provided by Dr. Robert Silverman (Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH). The study was approved by University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol no. 201102224.

Immunoblotting and real-time PCR

Snap-frozen mouse tissues were lysed and blotted with anti-TgPKR (H00005610-M02; Abnova) or anti-mouse PKR (sc-6282; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc). For protein analysis of hematopoietic progenitor cells, BM cells pooled from 5 mice were lineage depleted (kit 130-090-858, Miltenyi Biotec) and selected for c-Kit (130-091-224, Miltenyi Biotec) by the use of MACS microbeads; collected cells were lysed, and immunoblotting was performed with the use of either anti-ERK (no. 4695), phospho-ERK (no. 4370), eIF2α (no. 9722), phospho-eIF2α (no. 9721), or Mcl1 (no. 5453) antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology or interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1; sc-640), p21(sc-397), or CDK2 (sc-163) antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

Total RNAs were isolated from using RNeasy reagent (QIAGEN) and cDNA prepared (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan assays were performed for TgPKR (assay Hs00169345_m1) and mouse PKR (assay Mm01235644_m1) with β-actin as an endogenous control. PCR was conducted in a 7500 Fast RT-PCR system at 95°C for 20 seconds, 59°C for 20 seconds, and 72°C for 20 seconds for 40 cycles (Applied Biosystems).

In vitro culture and survival assays of BM progenitor cells

BM was harvested from femurs/tibias by flushing the marrow with 5 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% fetal bovine serum in a 27-gauge needle syringe. Red cells were lysed by ACK lysis buffer (0.15M NH4Cl, 10mM KHCO3, 0.1mM Na2EDTA, pH 7.4) and nucleated cells resuspended in PBS containing 10% fetal bovine serum and counted.

To measure hematopoietic colony formation, 2 × 104 whole BM nucleated cells from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice were plated in methylcellulose media (M3234; StemCell Technologies) containing 1× growth factor cocktail (3 U/mL erythropoietin [EPO], 10 ng/mL mouse IL-3, 10 ng/mL mouse interleukin [IL]-6, and 50 ng/mL mouse stem cell factor [SCF; R&D Systems]). Colonies were enumerated after 7 days with the use of light microscopy.

To assess progenitor cell survival during growth factor starvation, BM cells were cultured in various dilutions of the growth factor cocktail (0.0675× to 1×), and CFUs were measured. Apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry after annexin V staining. Where indicated, hematopoietic CFU was determined after culture of BM cells in either 300nM PKR inhibitor (PKRI) (Calbiochem) or various concentrations of TNF-α or IFN-γ. Radiation sensitivity was determined for CFUs after γ-irradiation of whole BM cells (1, 2, 3, or 4 Gy from a 60Co source delivered at 100 cGy/min).

CFU-spleen assays

Recipient mice 12 to 16 weeks of age were treated with 10 Gy of γ-irradiation. Then, 2 × 104 whole, nucleated donor BM cells were suspended in 200 μL of 1× PBS with 10% bovine calf serum (Bovogen) and administered intravenously to recipient mice. Ten days later, spleens of recipient mice were harvested, fixed (60% ethanol, 30% chloroform, 10% acetic acid), and colonies counted.

Flow cytometry and quiescence/cell-cycle analysis

BM mononuclear cells were stained with a fluorochrome-conjugated lineage antibody cocktail (CD3, B220, Ter119, CD11b, and Gr-1; BD Pharmingen), Sca-1, c-Kit, CD16/32, CD34, CD45, CD11b, and Gr-1 (ebioscience) and analyzed with a LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). To measure quiescence, Lin−c-Kit+ cells were isolated by the use of MACS columns (Miltenyi Biotec), fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, stained with propidium iodide (Invitrogen) and anti-Ki-67 PE (BD Pharmingen), and analyzed by flow cytometry. To measure proliferation and differentiation of stem/progenitor cells, 5 × 104 Lin−c-Kit+ cells isolated were cultured in RPMI-1640 media containing 1× growth factors. After 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 days, the cultured cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to c-Kit, CD11b, and Gr-1 and cell numbers determined by flow cytometry.

Complete blood count and pathology

Peripheral blood samples were collected from cheek bleed and complete blood counts obtained with a Hemavet analyzer (Drew Scientific, Inc). Histopathologic examination was performed on hematoxylin and eosin−stained specimens prepared from thymus, lymph nodes, spleen, kidney, lung, heart, and liver fixed in alcoholic-paraformaldahye solution and decalcified femur specimens were fixed in neutral-buffered 10% formalin. Bouin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned and deparaffinized. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. BM smears were prepared from femurs and stained with Wright-Geimsa.

Slides were viewed with an Olympus upright microscope equipped with U plan Fluorite objectives at 40×/0.75 and 100× oil/1.30 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and Cytoseal mounting medium. Images were acquired using a DP71 digital camera with DP-BSW-V3.1 camera control software and processed with Adobe Photoshop, version 7.0.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance (P < .05) was determined by Student t test with Graphpad Prism v. 5.0.

Results

Hematopoietic-tissue specific expression of TgPKR in mouse

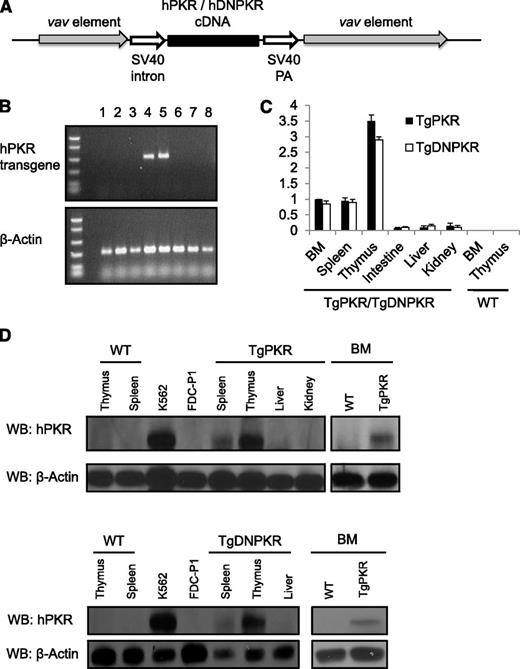

Transgenic mice were generated that express full-length TgPKR or a catalytically null TgDNPKR driven by the vav transcriptional elements to direct gene expression specifically in hematopoietic tissues (Figure 1A).19,20 Founder TgPKR or TgDNPKR mice were identified by PCR of genomic DNA (Figure 1B). Importantly, we found that TgPKR or DNPKR is highly expressed in thymus, spleen, and BM compared with nonhematopoietic tissues such as small intestine, liver, or kidney tissues as demonstrated by real-time quantitative PCR and western blotting (Figure 1C-D).

Mice are generated that express either a TgPKR or DNPKR mutant transgene exclusively in hematopoietic tissues. (A) Schematic of construct used for pronuclear injection. (B) PCR analysis of tail DNA to detect transgenic mice with primers specific for TgPKR. PCR for β-actin was used as an endogenous control. Lanes 4 and 5 are transgenic pups; others are WT siblings. (C) Real-time PCR assays of TgPKR or DNPKR expression in the indicated tissues of transgenic mice. Data represent relative mRNA levels (mean ± SEM, n = 3) normalized to mouse β-actin in arbitrary units. (D) Total cell lysates were analyzed by western blot for TgPKR or DNPKR protein expression in the tissues indicated.

Mice are generated that express either a TgPKR or DNPKR mutant transgene exclusively in hematopoietic tissues. (A) Schematic of construct used for pronuclear injection. (B) PCR analysis of tail DNA to detect transgenic mice with primers specific for TgPKR. PCR for β-actin was used as an endogenous control. Lanes 4 and 5 are transgenic pups; others are WT siblings. (C) Real-time PCR assays of TgPKR or DNPKR expression in the indicated tissues of transgenic mice. Data represent relative mRNA levels (mean ± SEM, n = 3) normalized to mouse β-actin in arbitrary units. (D) Total cell lysates were analyzed by western blot for TgPKR or DNPKR protein expression in the tissues indicated.

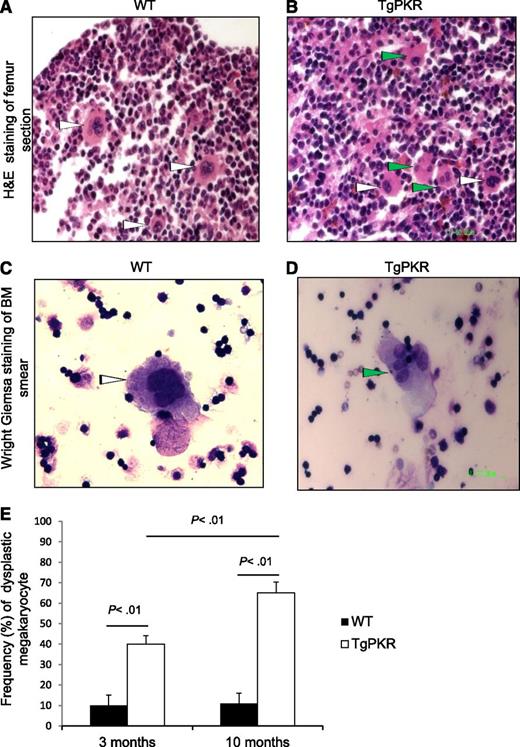

Transgenic expression of PKR induces histological features of BM dysplasia

BM from TgPKR or TgDNPKR mice was examined for histopathological abnormalities. Strikingly, more than 80% (16 of 19) of TgPKR mice display mild-to-moderate dysplastic changes in either erythroid, myeloid, or megakaryocytic cells (Figure 2A-D, green arrowheads). Furthermore, as TgPKR mice aged, megakaryocytic dysplasia increased from 40% in the 3-month-old group to 65% in the 10-month-old group (200 megakaryocytes counted per mouse; Figure 2E). In addition, TgPKR mice demonstrate increased marrow cellularity with an increase in myeloid and lymphoid blasts and mild necrosis. No significant BM abnormalities have yet been identified in TgDNPKR mice, indicating that the effect of PKR on hematopoiesis may require kinase activity (data not shown). In addition, a significant number of TgPKR mice developed dermatitis, which may indicate a condition of chronic inflammation (data not shown). For comparison, we examined PKRKO. Interestingly, although no significant differences in BM pathology were apparent, PKRKO mice display increased body weight of littermates (average weight: 39.2 g vs 32.7 g, n = 10, P < .01), and a larger average spleen size than WT mice when measured at 5 to 6 months of age (PKRKO [n = 7]: 0.98 g vs WT [n = 11]: 0.86 g; P = .034).

Transgenic expression of PKR induces BM dysplasia in TgPKR mice. (A and B) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of paraffin-embedded sections of femur (for BM) from WT control and TgPKR mice as indicated. White arrows point to normal megakaryocytes. Green arrows indicate dysplastic megakaryocytes with single nuclear lobe or with multiple separated nuclear lobes. (C and D) Wright-Giemsa staining of BM smears from WT control or TgPKR mice as indicated. White arrows indicate normal megakaryocytes. Green arrow indicates a dysplastic megakaryocyte with multiple separated nuclear lobes. (E) Graph showing percentage of dysplastic megakaryocytes in 3- vs 10-month-old WT or TgPKR mice. Five mice of each genotype were analyzed with 200 megakaryocytes counted per specimen.

Transgenic expression of PKR induces BM dysplasia in TgPKR mice. (A and B) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of paraffin-embedded sections of femur (for BM) from WT control and TgPKR mice as indicated. White arrows point to normal megakaryocytes. Green arrows indicate dysplastic megakaryocytes with single nuclear lobe or with multiple separated nuclear lobes. (C and D) Wright-Giemsa staining of BM smears from WT control or TgPKR mice as indicated. White arrows indicate normal megakaryocytes. Green arrow indicates a dysplastic megakaryocyte with multiple separated nuclear lobes. (E) Graph showing percentage of dysplastic megakaryocytes in 3- vs 10-month-old WT or TgPKR mice. Five mice of each genotype were analyzed with 200 megakaryocytes counted per specimen.

Analysis of peripheral blood indicates that TgPKR mice have significantly lower total white blood cell, neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet, and hemoglobin counts compared with WT mice, indicating defective hematopoiesis (Table 1). Furthermore, this trend becomes exaggerated as mice age for 16 to 18 months. In contrast, WBC, platelet and hemoglobin levels in PKRKO or TgDNPKR increase compared with WT mice, and the differences between the CBC of TgPKR and WT or TgDNPKR mice became more pronounced as the mice aged (Table 1). Taken together, these findings indicate that aberrant activation of PKR in the hematopoietic compartment may play a role in BM failure states. In addition, the absence of expression/activity of PKR during aging is clearly associated with increased numbers of hematopoietic cells.

Peripheral blood analyses of WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, and PKRKO mice

| . | WBC, ×109/L . | NE, ×109/L . | LY, ×109/L . | HGB, g/dL . | PLT, ×109/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3- to 4-mo old mice | |||||

| WT (n = 22) | 10.24 ± 0.65 | 2.01 ± 0.20 | 7.91 ± 0.50 | 13.33 ± 0.18 | 807.5 ± 29.49 |

| TgPKR (n = 21) | 7.83 ± 0.49 | 1.49 ± 0.15 | 5.99 ± 0.42 | 12.42 ± 0.31 | 670.6 ± 51.49 |

| P | .0056 | .0304 | .0056 | .0142 | .0245 |

| TgDNPKR (n = 20) | 13.60 ± 0.72 | 3.22 ± 0.21 | 10.05 ± 0.69 | 14.00 ± 0.16 | 877.3 ± 24.78 |

| P | .0012 | .0003 | .0154 | .0080 | .0809 |

| PKRKO (n = 11) | 10.40 ± 0.90 | 1.94 ± 0.30 | 8.03 ± 0.72 | 13.01 ± 0.41 | 840.5 ± 28.14 |

| P | .44 | .38 | .45 | .13 | .24 |

| 10-mo-old mice | |||||

| WT (n = 5) | 9.83 ± 0.60 | 1.65 ± 0.27 | 7.77 ± 0.31 | 13.40 ± 0.18 | 788.6 ± 25.95 |

| TgPKR (n = 5) | 5.57 ± 1.19 | 1.16 ± 0.37 | 4.03 ± 0.99 | 11.02 ± 0.53 | 421.6 ± 85.09 |

| P | .0124 | .3197 | .0068 | .0028 | .0033 |

| TgDNPKR (n = 5) | 15.32 ± 0.62 | 3.52 ± 0.31 | 11.48 ± 0.55 | 14.50 ± 0.16 | 922.8 ± 47.73 |

| P | .0002 | .0020 | .0004 | .0019 | .0387 |

| PKRKO (n=5) | 16.48 ± 1.83 | 3.544 ± 0.77 | 11.86 ± 1.01 | 12.72 ± 0.42 | 907.2 ± 43.90 |

| P | .0086 | .0492 | .0048 | .1719 | .0485 |

| 16- to 18-mo-old mice | |||||

| WT (n = 5) | 10.47 ± 1.40 | 2.09 ± 0.28 | 8.38 ± 1.12 | 11.14 ± 0.36 | 717 ± 43.4 |

| TgPKR (n = 5) | 5.18 ± 1.22 | 0.89 ± 0.24 | 4.29 ± 1.00 | 7.9 ± 0.91 | 401.2 ± 54.9 |

| P | .010 | .005 | .013 | .005 | .001 |

| TgDNPKR (n =5) | 15.42 ± 1.23 | 3.84 ± 0.40 | 11.58 ± 1.05 | 13.1 ± 0.34 | 855.8 ± 35.6 |

| P | 0.014 | 0.003 | 0.035 | 0.002 | 0.019 |

| PKRKO (n = 5) | 17.34 ± 1.86 | 5.11 ± 0.71 | 12.22 ± 1.21 | 14.56 ± 0.16 | 924 ± 39.08 |

| P | .009 | .002 | .024 | <.001 | .004 |

| . | WBC, ×109/L . | NE, ×109/L . | LY, ×109/L . | HGB, g/dL . | PLT, ×109/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3- to 4-mo old mice | |||||

| WT (n = 22) | 10.24 ± 0.65 | 2.01 ± 0.20 | 7.91 ± 0.50 | 13.33 ± 0.18 | 807.5 ± 29.49 |

| TgPKR (n = 21) | 7.83 ± 0.49 | 1.49 ± 0.15 | 5.99 ± 0.42 | 12.42 ± 0.31 | 670.6 ± 51.49 |

| P | .0056 | .0304 | .0056 | .0142 | .0245 |

| TgDNPKR (n = 20) | 13.60 ± 0.72 | 3.22 ± 0.21 | 10.05 ± 0.69 | 14.00 ± 0.16 | 877.3 ± 24.78 |

| P | .0012 | .0003 | .0154 | .0080 | .0809 |

| PKRKO (n = 11) | 10.40 ± 0.90 | 1.94 ± 0.30 | 8.03 ± 0.72 | 13.01 ± 0.41 | 840.5 ± 28.14 |

| P | .44 | .38 | .45 | .13 | .24 |

| 10-mo-old mice | |||||

| WT (n = 5) | 9.83 ± 0.60 | 1.65 ± 0.27 | 7.77 ± 0.31 | 13.40 ± 0.18 | 788.6 ± 25.95 |

| TgPKR (n = 5) | 5.57 ± 1.19 | 1.16 ± 0.37 | 4.03 ± 0.99 | 11.02 ± 0.53 | 421.6 ± 85.09 |

| P | .0124 | .3197 | .0068 | .0028 | .0033 |

| TgDNPKR (n = 5) | 15.32 ± 0.62 | 3.52 ± 0.31 | 11.48 ± 0.55 | 14.50 ± 0.16 | 922.8 ± 47.73 |

| P | .0002 | .0020 | .0004 | .0019 | .0387 |

| PKRKO (n=5) | 16.48 ± 1.83 | 3.544 ± 0.77 | 11.86 ± 1.01 | 12.72 ± 0.42 | 907.2 ± 43.90 |

| P | .0086 | .0492 | .0048 | .1719 | .0485 |

| 16- to 18-mo-old mice | |||||

| WT (n = 5) | 10.47 ± 1.40 | 2.09 ± 0.28 | 8.38 ± 1.12 | 11.14 ± 0.36 | 717 ± 43.4 |

| TgPKR (n = 5) | 5.18 ± 1.22 | 0.89 ± 0.24 | 4.29 ± 1.00 | 7.9 ± 0.91 | 401.2 ± 54.9 |

| P | .010 | .005 | .013 | .005 | .001 |

| TgDNPKR (n =5) | 15.42 ± 1.23 | 3.84 ± 0.40 | 11.58 ± 1.05 | 13.1 ± 0.34 | 855.8 ± 35.6 |

| P | 0.014 | 0.003 | 0.035 | 0.002 | 0.019 |

| PKRKO (n = 5) | 17.34 ± 1.86 | 5.11 ± 0.71 | 12.22 ± 1.21 | 14.56 ± 0.16 | 924 ± 39.08 |

| P | .009 | .002 | .024 | <.001 | .004 |

Complete blood count analyses were performed with TgPKR, TgDNPKR mice, and their WT or PKRKO mice. Statistical significance (P) compared with WT was calculated by Student t test.

HGB indicates hemoglobin; LY, lymphocyte; NE, neutrophil; PLT, platelet; WBC, white blood cells.

PKR expression affects proliferation and differentiation of HSPCs

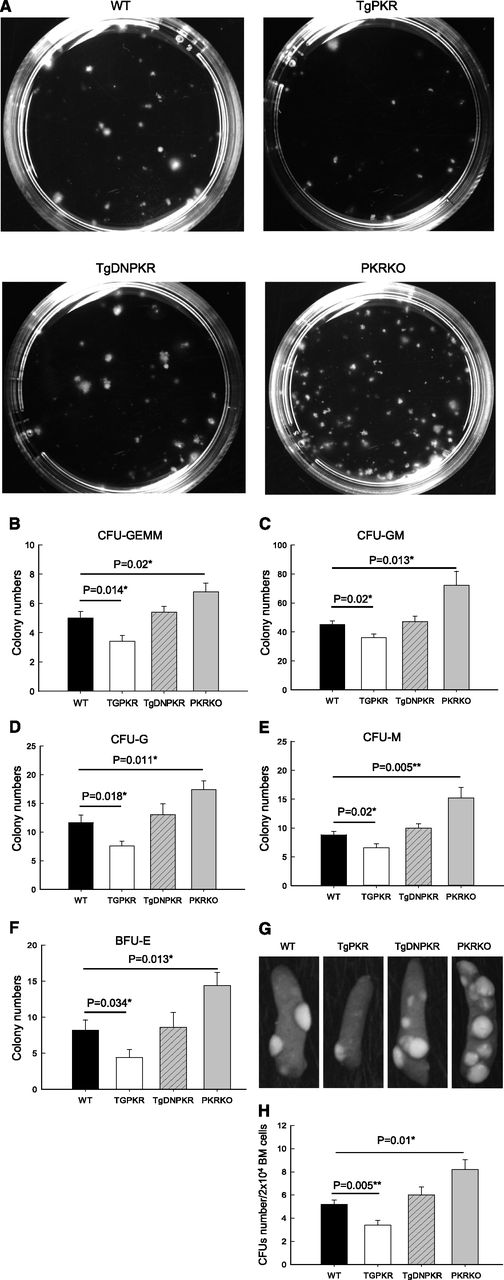

To investigate whether aberrant expression/activation of PKR may affect proliferation and/or differentiation of HSPCs and to explain the changes observed in peripheral or BM, we carried out hematopoietic colony-forming cell assays by using BM isolated from TgPKR, TgDNPKR, PKRKO, and WT mice. Results show HSPCs of TgPKR mice gave rise to significantly fewer CFUs that were smaller in size compared with WT control mice (Figure 3A). Furthermore, PKRKO BM contained increased numbers of CFUs compared with WT mice, a previously unrecognized phenotype for the PKR-null mice (Figure 3A). These findings indicate that PKR expression may directly affect growth of HSPCs.

PKR regulates clonogenic potential of BM progenitors both in vitro and in vivo. (A) Representative colonies after culture of WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO BM cells from 3- to 5-month-old mice in methylcellulose for 7 days. (B-F) Unfractionated BM cells (2 × 104 for B, C, D, and E, 105 for F) from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice were plated and resulting CFU-GEMM (B), CFU-GM (C), CFU-G (D), CFU-M (E), and BFU-E (F) counted. BM from 5 mice of each genotype was assayed and mean ± SEM graphed. (G) Representative examples of macroscopic spleen colonies (CFU-S) from WT irradiated recipients injected with 2 × 104 unfractionated BM cells either from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice as indicated. (H) Colonies were counted 10 days after transplantation. Graphs represent mean ± SEM (n = 4 donor mice of each genotype).

PKR regulates clonogenic potential of BM progenitors both in vitro and in vivo. (A) Representative colonies after culture of WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO BM cells from 3- to 5-month-old mice in methylcellulose for 7 days. (B-F) Unfractionated BM cells (2 × 104 for B, C, D, and E, 105 for F) from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice were plated and resulting CFU-GEMM (B), CFU-GM (C), CFU-G (D), CFU-M (E), and BFU-E (F) counted. BM from 5 mice of each genotype was assayed and mean ± SEM graphed. (G) Representative examples of macroscopic spleen colonies (CFU-S) from WT irradiated recipients injected with 2 × 104 unfractionated BM cells either from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice as indicated. (H) Colonies were counted 10 days after transplantation. Graphs represent mean ± SEM (n = 4 donor mice of each genotype).

Breakdown of hematopoietic colony types show that the TgPKR mice have impaired formation of multipotent CFUs (CFU-GEMM), bipotent granulocyte macrophage (CFU-GM), unipotent granulocyte (CFU-G), macrophage (CFU-M), and burst-forming unit erythroid (BFU-E) colonies, indicating a global impairment of progenitor cell differentiation toward the myeloid lineage (Figure 3B-F). By contrast, BM from PKRKO mice display an increase in the frequency of all myeloid lineages, including CFU-GEMM, CFU-GM, CFU-G, CFU-M, CFU-E, and BFU-E (Figure 3B-F).

To assess the function of HSPCs, we performed an in vivo CFU-spleen assay. Consistent with the findings of the in vitro colony-forming cell assay, TgPKR BM gave rise to significantly fewer whereas PKRKO BM gave rise to significantly more CFU-S compared with WT (Figure 3G-H). These results indicate that the HSPCs from TgPKR mice are less frequent and/or have an impaired capacity to reconstitute multilineage hematopoiesis compared with cells from PKRKO mice. Thus, PKR may have a regulatory role in the full and robust proliferation and differentiation of HSPCs.

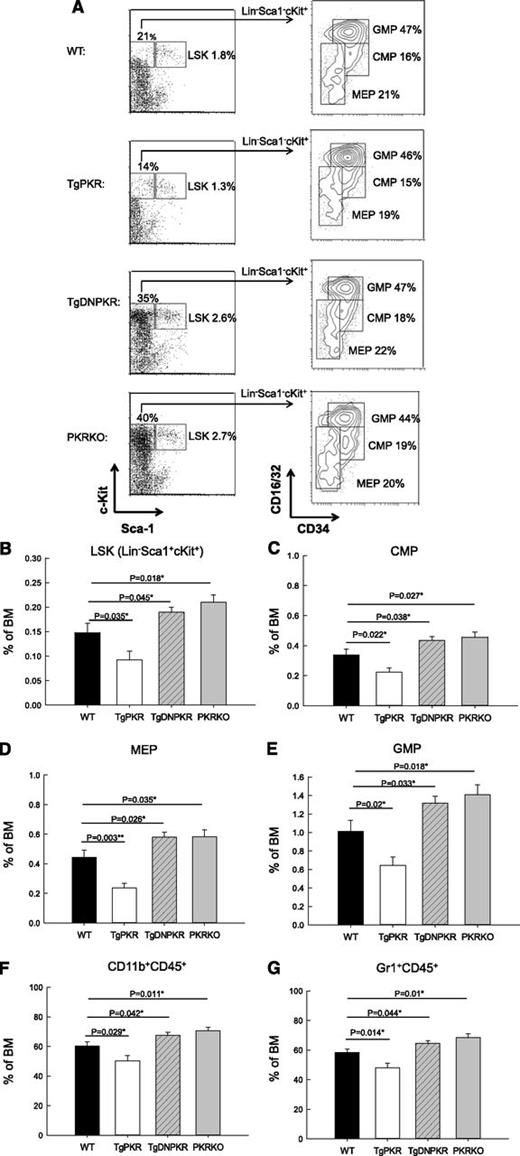

Frequencies of HSPC populations are altered in the BM of TgPKR and PKRKO mice

To investigate whether PKR affects HSPCs populations in vivo, BM cells were isolated and analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 4A). TgPKR mice were found to have a significant decrease in the number of hematopoietic stem cells (LSK: Lin−,Sca1+,cKit+) as well as common myeloid progenitor cells (CMP: Lin−,Sca1−,cKit+,CD34+,CD16/32low) compared with WT mice (Figure 4B-C). Furthermore, both megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor (MEP: Lin−,Sca1−,cKit+, CD16/32low,CD34−) and granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (GMP: Lin−,Sca1−,cKit+, CD16/32+,CD34+) populations are decreased in TgPKR mice compared with WT mice. In contrast, both TgDNPKR and PKRKO mice have significantly elevated numbers of BM-derived HSPCs (Figure 4A-E). Although the number of HSPCs varies greatly between WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, and PKRKO mice, the distribution of CMP, GMP, and MEP populations remained similar (Figure 4A). Therefore, the inhibitory effect of PKR expression/activation on the differentiation of BM HSPCs does not affect a specific lineage.

In vivo sizes of HSPC compartments and development of granulocyte/monocytes is altered in TgPKR transgenic and PKR knockout mice. (A) BM from 3- to 5-month-old mice was stained for lineage markers Lin, Sca-1, c-Kit, CD34, and CD16/32. The CD34 and CD16/32 staining of the Lin−, c-Kit+ subset was used to discriminate between hematopoietic progenitor cell populations. (B) Graph depicting the relative frequency of LSK hematopoietic stem cells in total BM. (C) The frequency of CMP cells in BM. (D) The frequency of MEP cells in total BM. (E) The frequency of GMP cells in total BM. (F) BM was stained for the monocyte marker CD11b and measured by flow cytometry. Graph shows the frequency of CD45+CD11b+ monocytes in total BM. (G) Graph of the average relative frequency of granulocytes (CD45+Gr-1+) in total BM cells. For all graphs the average data from 5 mice of each genotype is represented.

In vivo sizes of HSPC compartments and development of granulocyte/monocytes is altered in TgPKR transgenic and PKR knockout mice. (A) BM from 3- to 5-month-old mice was stained for lineage markers Lin, Sca-1, c-Kit, CD34, and CD16/32. The CD34 and CD16/32 staining of the Lin−, c-Kit+ subset was used to discriminate between hematopoietic progenitor cell populations. (B) Graph depicting the relative frequency of LSK hematopoietic stem cells in total BM. (C) The frequency of CMP cells in BM. (D) The frequency of MEP cells in total BM. (E) The frequency of GMP cells in total BM. (F) BM was stained for the monocyte marker CD11b and measured by flow cytometry. Graph shows the frequency of CD45+CD11b+ monocytes in total BM. (G) Graph of the average relative frequency of granulocytes (CD45+Gr-1+) in total BM cells. For all graphs the average data from 5 mice of each genotype is represented.

To assess whether the development of mature myeloid cells is affected by PKR expression, BM cells from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice were stained for mature myeloid lineage markers to measure the CD45+CD11b− and CD45+Gr-1+ populations. Significantly, BM from TgPKR mice displayed a 17% decrease in the CD45+CD11b+ and an 18% decrease in the CD45+Gr-1+ population compared with WT control (Figure 4F-G). In contrast, BM from PKRKO mice display a 17% and 25% increase, respectively, in CD45+CD11b+ and CD45+Gr-1+ populations compared with WT mice (Figure 4F-G). Collectively, these results confirm that PKR is a necessary regulator of HSPCs.

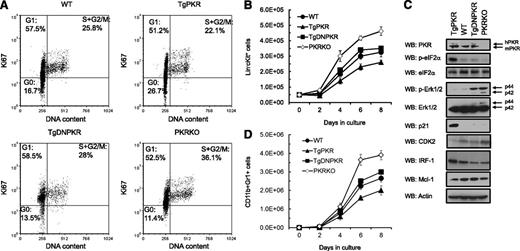

PKR regulates cell-cycle distribution and quiescence status of HSPCs

Because impaired function of HSPCs may result from alterations in proliferation, we performed cell-cycle analysis by measuring Ki67 to distinguish dividing from resting/quiescent (G0) cells. Significantly, the HSPC Lin−cKit+ population of 3- to 5-month-old TgPKR mice had a greater percentage of quiescent G0 cells with fewer proliferating cells in S|+|G2/M phases compared with WT mice (Figure 5A). In addition, results indicate that PKR activity is required for this effect because the cell-cycle distribution of TgDNPKR and WT is similar. However, Lin−cKit+ cells from PKRKO mice have a markedly reduced frequency of quiescent (G0) and a greater percent of proliferating (S|+|G2/M) cells compared with WT (Figure 5A).

PKR regulates quiescence and cell-cycle progression of HSPCs. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of DNA content and Ki67 expression in Lin−c-Kit+ BM cells from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice. Numbers on the plot are the frequency of cells in the indicated cell-cycle phases. (B) Proliferation of Lin−c-Kit+ BM cells from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice in vitro under standard growth conditions was measured by flow cytometry (n = 5). (C) Western blotting of Lin−c-Kit+ BM cells from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice to investigate the mechanisms of PKR-dependent proliferation and cell cycle regulation. The cells from 5 mice for each genotype were pooled for western blotting. (D) Differentiation of Lin−c-Kit+ cells from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice into CD11b+Gr1+ cells was measured by flow cytometry after culture under standard growth conditions.

PKR regulates quiescence and cell-cycle progression of HSPCs. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of DNA content and Ki67 expression in Lin−c-Kit+ BM cells from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice. Numbers on the plot are the frequency of cells in the indicated cell-cycle phases. (B) Proliferation of Lin−c-Kit+ BM cells from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice in vitro under standard growth conditions was measured by flow cytometry (n = 5). (C) Western blotting of Lin−c-Kit+ BM cells from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice to investigate the mechanisms of PKR-dependent proliferation and cell cycle regulation. The cells from 5 mice for each genotype were pooled for western blotting. (D) Differentiation of Lin−c-Kit+ cells from WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice into CD11b+Gr1+ cells was measured by flow cytometry after culture under standard growth conditions.

Consistent with an inhibitory effect on the cell cycle, increased PKR expression inhibits HSPC proliferation when cultured in vitro. For example, after 8 days’ growth, there was a 20% decrease in the number TgPKR Lin−cKit+ cells compared with WT cells (Figure 5B, P < .01). Conversely, HSPCs isolated from PKRKO mice had a significantly greater proliferation rate, with 42% more cells than WT after 8 days in culture (Figure 5B, P < .01). This inhibitory effect of PKR on HSPC proliferation translates to terminally differentiated cells in which TgPKR Lin−cKit+ cells give rise to 25% fewer, whereas the PKRKO cells produce 47% more CD11b+Gr+ cells (Figure 5C).

To investigate the mechanism(s) involved in PKR-mediated inhibition of HSPC proliferation, western blotting was performed on Lin−cKit+ cell lysates. Significantly, HSPCs from TgPKR mice display increased levels of several potent negative regulators of proliferation, including phospho-eIF2α, IRF-1, and p21. In contrast, cells from TgDNPKR or PKRKO mice displayed decreased IRF-1 and increased phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2 (Figure 5D). Furthermore, HSPCs from PKRKO mice had decreased CDK2 (Figure 5D). These findings support previous reports that PKR is required for eIF2α− and IRF-1−induced inhibition of cell growth.6,21,22

PKR regulates stress survival of HSPCs in response to growth factor deprivation, inflammatory cytokines, or irradiation

To test whether PKR may play a role in regulating the response to stress in HSPCs, we measured cell survival after the application of various stresses in clonogenic assays. First, we investigated whether PKR expression may affect the sensitivity to hematopoietic growth factor (HGF) deprivation. After culture of HSPCs for increasing time in the absence of factors, cells were plated in methylcellulose containing SCF, IL-3, IL-6, and EPO and colonies scored after 7 days. HSPCs isolated from TgPKR mice were significantly more sensitive to HGF deprivation with decreased survival exhibiting a half-life (ie, time of deprivation at which 50% progenitor cell colonies survive) of 28 hours compared with 36 hours for WT cells (P < .01, Figure 6A). Importantly, cells from the PKRKO mice were highly resistant to factor deprivation; they exhibited a half-life of 54 hours (P < .01; Figure 6A). In addition, Annexin V analysis confirms that reduced survival results from increased apoptosis in TgPKR and reduced apoptosis in TgDNPKR and PKRKO cells (Figure 6B). Interestingly, PKRKO cells display greater CFU efficiency in lower concentrations of HGFs (left shift of curve) compared with WT cells. In contrast, cells from TgPKR mice require more than 4 times the dose of HGFs to achieve the same 100% CFU efficiency as WT cells (ie, right shift of curve; Figure 4C).

PKR regulates survival of clonogenic BM progenitor cells in vitro after hematopoietic growth factor deprivation, inflammatory cytokine treatment, or γ-irradiation. The colony formation data are expressed as percent of maximal numbers of colonies. Mean actual maximal colony counts per 2 × 104 cells were WT = 70.4, TgPKR = 53.4, TgDNPKR = 77, and PKRKO = 111.6. (A) BM cells were cultured in media without growth factors for the indicated times. Cells (2 × 104) were then plated in methylcellulose-based media containing 1× growth factors (50 ng/mL SCF, 10 ng/mL IL-3, 10 ng/mL IL-6, and 3U/mL EPO) and colonies scored after 7 days (n = 3). (B) Lin−c-Kit+ cells were isolated from BM of WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice and cultured in media without growth factors. At the indicated times, measurement of Annexin V staining was performed by flow cytometry to determine apoptosis. (n = 3). (C) BM cells (2 × 104) were plated in methylcellulose-based media containing various concentrations of the hematopoietic growth factor cocktail (0.0675× to 1×, 1× = 50 ng/mL SCF, 10 ng/mL IL-3, 10 ng/mL IL-6, and 3U/mL EPO) and hematopoietic colony formation scored. (D-G) Cells (2 × 104) were plated in methylcellulose-based media containing various concentrations of the hematopoietic growth factor cocktail and 300nM of either PKRI or inactive control. (H) Hematopoietic colony formation was assayed in medium containing 1× growth factors and the indicated concentration of IFN-γ. (I) Hematopoietic colony formation was assayed in medium containing 1× growth factors and the indicated concentration of TNF-α. (J) Hematopoietic colony formation was assayed after irradiation of BM cells with the indicated doses of γ-irradiation. (For all colony-formation assays, colonies were scored after 7 days’ growth and results are the average of BM from 3 mice [n = 3] for each genotype.)

PKR regulates survival of clonogenic BM progenitor cells in vitro after hematopoietic growth factor deprivation, inflammatory cytokine treatment, or γ-irradiation. The colony formation data are expressed as percent of maximal numbers of colonies. Mean actual maximal colony counts per 2 × 104 cells were WT = 70.4, TgPKR = 53.4, TgDNPKR = 77, and PKRKO = 111.6. (A) BM cells were cultured in media without growth factors for the indicated times. Cells (2 × 104) were then plated in methylcellulose-based media containing 1× growth factors (50 ng/mL SCF, 10 ng/mL IL-3, 10 ng/mL IL-6, and 3U/mL EPO) and colonies scored after 7 days (n = 3). (B) Lin−c-Kit+ cells were isolated from BM of WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice and cultured in media without growth factors. At the indicated times, measurement of Annexin V staining was performed by flow cytometry to determine apoptosis. (n = 3). (C) BM cells (2 × 104) were plated in methylcellulose-based media containing various concentrations of the hematopoietic growth factor cocktail (0.0675× to 1×, 1× = 50 ng/mL SCF, 10 ng/mL IL-3, 10 ng/mL IL-6, and 3U/mL EPO) and hematopoietic colony formation scored. (D-G) Cells (2 × 104) were plated in methylcellulose-based media containing various concentrations of the hematopoietic growth factor cocktail and 300nM of either PKRI or inactive control. (H) Hematopoietic colony formation was assayed in medium containing 1× growth factors and the indicated concentration of IFN-γ. (I) Hematopoietic colony formation was assayed in medium containing 1× growth factors and the indicated concentration of TNF-α. (J) Hematopoietic colony formation was assayed after irradiation of BM cells with the indicated doses of γ-irradiation. (For all colony-formation assays, colonies were scored after 7 days’ growth and results are the average of BM from 3 mice [n = 3] for each genotype.)

As a control, we tested whether a pharmacological PKRI could rescue reduced CFU activity of TgPKR cells. Our results demonstrate that 300nM PKRI can significantly enhance colony formation of TgPKR cells in response to low concentrations of HGFs (Figure 6D). Although colony formation was moderately increased by the treatment of WT cells with PKRI, little or no effect was observed in TgDNPKR or PKRKO BM (Figure 6E-G). These data strongly indicate that PKR activity is required for its inhibitory effect on hematopoiesis.

To examine the role of PKR during the response to inflammatory cytokines, BM cells were plated in methylcellulose medium containing HGFs with increasing concentrations of IFN-γ or TNF-α.17 Both cytokines suppress CFU more potently in cells from TgPKR compared with WT mice (Figure 6H-I). Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of these cytokines was significantly reduced on TgDNPKR or PKRKO HSPCs, suggesting that activation of PKR is necessary for the myelosuppressive effect of inflammatory cytokines.

We next assessed the effect of PKR on radiosensitivity of BM cells in vitro. Cells were plated as described previously and immediately exposed to increasing doses of γ irradiation. HSPCs from TgPKR mice were found to be significantly more sensitive to irradiation as evidenced by a lower D37 (the radiation dose for a survival of 37%) of 1.48 Gy (P < .05) and a reduced SF2Gy (surviving fraction at 2Gy irradiation) of only 22.0% (P < .05) compared with a D37 of 2.05 Gy and SF2Gy of 41.6% for WT cells (Figure 6J). Moreover, HSPCs from the PKRKO mice were highly resistant to radiation exposure with a D37 of 2.68 Gy (P < .05) and an SF2Gy of 60.7% (P < .05), respectively (Figure 6J). Thus, inhibition or loss of expression of PKR may prevent the myelosuppressive effect of irradiation.

Discussion

The loss of PKR expression/activity has been reported in hematological malignancies, including B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, whereas activated PKR is reported to occur in close association with MDS in primary patient samples.13,15,18 This finding suggests that PKR may play a role in regulating normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Therefore, we developed mice expressing either a TgPKR or DNPKR transgene specifically in hematopoietic tissues and examined hematopoiesis in these mice and in PKR knockout mice. Although a CMV-driven PKR transgenic mouse model has been reported, no effect was noted on hematopoiesis because the transgene was not expressed in hematopoietic tissues.23 Significantly, results from our vav-driven transgenic PKR mouse clearly indicate that PKR plays a role in regulating hematopoiesis. Specifically, increased PKR expression/activation in TgPKR cells leads to features of defective hematopoiesis and BM failure as demonstrated by mild pancytopenia of all peripheral blood elements. In addition, the BM of TgPKR mice contains dysplasic-appearing cells, reduced HSPC populations, reduced hematopoietic colony-forming capacity, and increased sensitivity to various stresses that mediate cell death when compared with cells from WT mice. Furthermore, an increased percentage of HSPCs isolated from TgPKR mice are quiescent (G0) compared with WT mice. Because an effective exit from quiescence into S+G2/M phases is necessary for the expansion of the HSPC pool, the lower proliferation rate of the TgPKR HSPCs may, at least in part, explain the reduced numbers and frequency of HSPC populations, including LSK, CMP, GMP, and MEP, observed in these mice. Furthermore, suppression of myeloid differentiation with increased sensitivity to stress mediated apoptosis may in turn cause inefficient terminal differentiation of blood cells, resulting in lower peripheral blood cell counts as observed.

Significantly, PKR-null mice display markedly increased numbers of HSPCs with an increased potential for hematopoietic colony formation. To account for this, results indicate that the frequency of HSPCs in active proliferation, as measured by Ki67 expression, is increased. We hypothesize that activated PKR inhibits hematopoiesis by mechanism(s) involving reduced protein synthesis and decreased survival after stress. In support of this notion, BM progenitor cells isolated from PKRKO mice express decreased basal levels of phospho-eIF2α, increased levels of phospho-extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2, and increased CDK2, indicating that mechanisms of proliferation are activated in these cells. Thus, dynamic activation/inactivation of PKR during homeostasis is expected to regulate HSPC numbers.

Interestingly, despite having increased numbers of HSPCs and displaying increased CFU potential, PKRKO mice have no differences in BM histopathology compared with WT mice. However, they do display significantly increased peripheral blood cell counts upon aging compared with WT mice. To account for this, we suspect an uncharacterized feedback mechanism may limit inappropriate differentiation of PKRKO HSPCs under basal (nonstress) conditions. Importantly, the effect of PKR on hematopoiesis becomes most evident under times of cell stress. For example, BM cells from PKRKO mice are significantly more resistant to cell death resulting from growth factor starvation, inflammatory cytokine treatment, and irradiation. Thus, we propose that the primary role for PKR in HSPCs is to potentiate the stress response and that loss of PKR activity may lead to increased cell survival after stress, whereas overexpression and activation may decrease cell viability. In support of this, others have reported that PKR-null mice are protected from DMBA-induced BM toxicity leading to hypocellularity.24 Furthermore, although PKR-null mice have not been reported to develop spontaneous tumors or leukemia during their normal 2 year lifespan, we hypothesize that these mice will be more susceptible to transformation by genotoxic stimuli or oncogenic driver mutations because the mice are predisposed to withstand stress.

Collectively, results here indicate that PKR may be a critical factor in the pathogenesis of some BM failure states, potentially including MDS. Increased activity and aberrant subcellular location of PKR have been reported in CD34+ myeloid progenitor cells isolated from high-risk MDS patients, whereas the loss of PKR expression/activity has been reported in BM cells from leukemia patients.13,15,18 In the present study, results indicate that the majority (>80%) of TgPKR mice develop dysplastic BM changes as in the development of BM failure syndromes.25,26 In addition, TgPKR mice display increased marrow cellularity with greater numbers of myeloid and lymphoid blasts as well as mild necrosis. This phenomenon may have clinical relevance because BM from patients with MDS typically displays hypercellularity (attributable to inhibition of terminal differentiation) with enhanced apoptosis/necrosis. These results suggest that inhibition of PKR may be a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of marrow failure syndromes that display elevated levels of PKR. In addition, in BM transplantation and therapy-related BM suppression/ablation, inhibition of PKR activity might be a novel method to accelerate hematopoietic reconstitution.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ryan Fiske and the University of Florida transgenic animal core for assistance in developing the PKR transgenic mice.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute award R01 HL054083 and Florida Department of Health Bankhead Coley award 09BW-06.

Authorship

Contribution: X.L. and R.L.B performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; X.C., M.B., and M.K.R. performed research; and W.S.M. analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: W. Stratford May Jr., Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology and Oncology, University of Florida, 2033 Mowry Rd, Box 103633, Gainesville, FL 32610; e-mail: smay@ufl.edu.

References

Author notes

X.L. and R.L.B. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 6. PKR regulates survival of clonogenic BM progenitor cells in vitro after hematopoietic growth factor deprivation, inflammatory cytokine treatment, or γ-irradiation. The colony formation data are expressed as percent of maximal numbers of colonies. Mean actual maximal colony counts per 2 × 104 cells were WT = 70.4, TgPKR = 53.4, TgDNPKR = 77, and PKRKO = 111.6. (A) BM cells were cultured in media without growth factors for the indicated times. Cells (2 × 104) were then plated in methylcellulose-based media containing 1× growth factors (50 ng/mL SCF, 10 ng/mL IL-3, 10 ng/mL IL-6, and 3U/mL EPO) and colonies scored after 7 days (n = 3). (B) Lin−c-Kit+ cells were isolated from BM of WT, TgPKR, TgDNPKR, or PKRKO mice and cultured in media without growth factors. At the indicated times, measurement of Annexin V staining was performed by flow cytometry to determine apoptosis. (n = 3). (C) BM cells (2 × 104) were plated in methylcellulose-based media containing various concentrations of the hematopoietic growth factor cocktail (0.0675× to 1×, 1× = 50 ng/mL SCF, 10 ng/mL IL-3, 10 ng/mL IL-6, and 3U/mL EPO) and hematopoietic colony formation scored. (D-G) Cells (2 × 104) were plated in methylcellulose-based media containing various concentrations of the hematopoietic growth factor cocktail and 300nM of either PKRI or inactive control. (H) Hematopoietic colony formation was assayed in medium containing 1× growth factors and the indicated concentration of IFN-γ. (I) Hematopoietic colony formation was assayed in medium containing 1× growth factors and the indicated concentration of TNF-α. (J) Hematopoietic colony formation was assayed after irradiation of BM cells with the indicated doses of γ-irradiation. (For all colony-formation assays, colonies were scored after 7 days’ growth and results are the average of BM from 3 mice [n = 3] for each genotype.)](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/121/17/10.1182_blood-2012-09-456400/4/m_3364f6.jpeg?Expires=1767702800&Signature=dW7k8We4yA-Y2J2bPvbUsBMpLN-khbFHTkWXDRTV-gAQNouQpr9Zsjlmf1t7Hhxf246wKTzuAhPVZPBa-JfdCE1kPyuRyrM0uvSI9Bd-xO9GHkIOUxafaEmixoIj9iuWRaEbgwCzoth56v55VvVc7nlwGJCMADmU5P9LFITKDSqBc3mfbkR3rnbFvS-d30mlWnmFOzxwRdpvvh6YVEoqklwaGmP5PTMF2LJN~O0W3F8kIfYkMgsD2H2pCFG-03d3a3-hOgYvj68UtMNafrvIb8SjnBr-YbrTG7ItYlTxo~YYtcrHIdHfR79KjV7dUWt9BAwp7KuRP~xaaZtSHpv9cA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal