Abstract

Lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors with down-regulated megakaryocyte-erythroid (MkE) potential are restricted to cells with high levels of cell-surface FLT3 expression, whereas HSCs and MkE progenitors lack detectable cell-surface FLT3. These findings are compatible with FLT3 cell-surface expression not being detectable in the fully multipotent stem/progenitor cell compartment in mice. If so, this process could be distinct from human hematopoiesis, in which FLT3 already is expressed in multipotent stem/progenitor cells. The expression pattern of Flt3 (mRNA) and FLT3 (protein) in multipotent progenitors is of considerable relevance for mouse models in which prognostically important Flt3 mutations are expressed under control of the endogenous mouse Flt3 promoter. Herein, we demonstrate that mouse Flt3 expression initiates in fully multipotent progenitors because in addition to lymphoid and granulocyte-monocyte progenitors, FLT3− Mk- and E-restricted downstream progenitors are also highly labeled when Flt3-Cre fate mapping is applied.

Introduction

Several recent observations suggested that the first lineage restriction step of mouse HSCs does not result in strictly separated common myeloid and common lymphoid commitment pathways. Rather, the earliest step in lymphopoiesis appears to result in the establishment of primitive lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors (LMPPs) with down-regulated megakaryocyte-erythroid (MkE) transcriptional priming and lineage potentials, but sustained granulocyte-monocyte (GM) and lymphoid potentials.1,2 In further support of the lymphoid commitment pathway sustaining GM (but not MkE) potential, the earliest thymic progenitors have combined T and GM potential.3,4 The existence of adult and fetal GM-lymphoid–restricted mouse MPPs has been confirmed through alternative approaches,2,5-8 and recently a similar progenitor was also identified in human hematopoiesis.9,10 The restriction of mouse LMPPs to the fraction of LIN−SCA1+KIT+ (LSK) cells with high cell–surface FMS-like tyrosine kinase receptor 3 (FLT3) expression and of long-term self-renewing HSCs to LSK cells lacking detectable cell-surface FLT3 expression11-13 raises the question as to what stage of lineage commitment FLT3 (protein) and Flt3 (mRNA) expression is initiated. Notably, the expression of FLT3 in human hematopoiesis appears to initiate already in multipotent stem or progenitor cells with sustained MkE potential,14,15 differing from the apparent expression pattern in multipotent progenitors in mice. If so, it could have important implications for mouse models in which activating Flt3 mutations, which are among the most common mutations in human acute myeloid leukemia,16 are expressed under control of the mouse Flt3 promoter.17,18

To more conclusively establish at which level in the mouse HSC and MPP hierarchy Flt3 mRNA expression is initiated, we investigated Flt3 expression at the single-cell level and also applied a Flt3-Cre fate mapping approach19 to establish to what degree progenitors of different cell lineages are derived through Flt3-expressing multipotent stem and progenitor cells.

Methods

Mice

Fluorescence-activated cell staining and sorting

BM cells and thymocytes were stained with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies as previously described1,21,22 and analyzed on a FACS LSRII (BD Biosciences) or sorted on a FACSAriaIIu Special Order Research Products (BD Biosciences). For specifics on the antibodies used and further details, see supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Transplantation assays

Lethally irradiated (9 Gy) C57BL/6 CD45.1 mice were transplanted with 2 million BM cells from 7- to 11-week-old Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ mice. CD45.2+LSKEYFP+ or CD45.2+LSKEYFP− cells were transplanted into secondary lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipients.

MkE potential

MkE potential was evaluated as previously described.5 For details, see supplemental Methods.

Gene expression analysis

Results and discussion

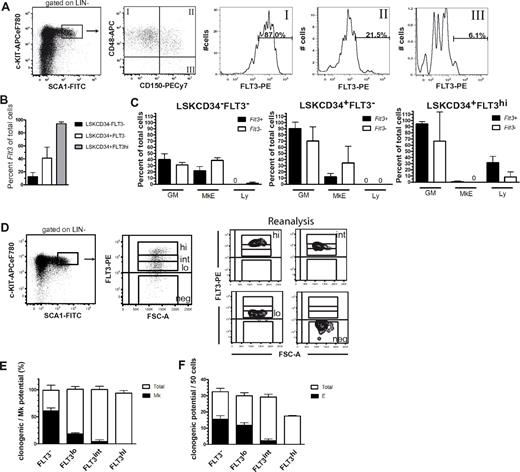

SLAM markers CD150 and CD48 allow separation of HSCs (LSKCD150+CD48−) and MPPs (LSKCD150−CD48+) in the BM LSK compartment.24 By using a PE-conjugated antibody excited by a high-powered green laser to enhance the detection of cell-surface FLT3, we found that only a small fraction (6%) of LSKCD150+CD48− cells expressed detectable FLT3 at low levels, whereas most LSKCD150−CD48+ MPPs expressed FLT3 at greater but variable levels, and a fraction of LSKCD150+CD48+ cells expressed FLT3 at intermediate levels (Figure 1A). By using a highly sensitive single-cell PCR, we found that a small faction (12.6%) of HSCs defined through another cell-surface phenotype (LSKCD34−FLT3−22 ) and a larger fraction (41.0%) of LSKCD34+FLT3− MPPs expressed Flt3 transcripts (Figure 1B), despite undetectable cell surface FLT3, suggesting that Flt3 transcriptional activation might initiate already in the HSC and MPP compartments. Moreover, the results of multiplex single-cell PCR demonstrated that Flt3+ HSCs and MPPs were not only transcriptionally activated for GM but also MkE lineage programs, although less than Flt3− cells (Figure 1C).

Cell-surface FLT3 expression in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell subsets. (A) FACS profiles from a representative mouse showing gating strategy for cell-surface FLT3 expression within LSKCD48+CD150−, LSKCD48+CD150+, and LSKCD48−CD150+ BM cells. Numbers indicate mean percentages of FLT3+ cells within each of the indicated gates, from 2 pools of BM cells, each from 3 mice. (B) Flt3 mRNA expression of single BM LSK subpopulations. Only cells that were Kit+ were included in analysis (86%-94% of all cells investigated). Data are expressed as mean (SD). For each population, a total of 176 cells were analyzed in 2 experiments. (C) Expression of different lineage programs in Flt3+ and Flt3− subsets of BM LSK populations. Cells were purified according to the indicated phenotypes and analyzed for expression of transcriptional programs for the GM (Csf3r, Mpo), MkE (Epor, Gata1, Vwf), and lymphoid (Ly; sterile Igh transcript, Rag1, Il7r) lineages. For a population to be classified as positive for a lineage-specific transcriptional program, transcripts of at least one of the aforementioned indicated lineage-specific genes should be detected. Mean (SD) results from 2 independent experiments with 88 single cells analyzed in each experiment. (D) Sorting strategy and purity analysis of LSKFLT3−, LSKFLT3lo, LSKFLT3int, and LSKFLT3hi cells isolated from 8- to 12-week-old WT mice. BM LSK cells were as indicated separated into 4 fractions on the basis of differential FLT3 expression. To the right is shown purity analysis for each of the fractions. (E) Mk potential of LSK cells separated on the basis of level of FLT3 expression. A total of 120 cells were plated of each cell population in each experiment. Mean (SD) results from 2 experiments. (F) Erythroid potential of LSK cells separated on the basis of levels of FLT3 expression. A total of 50 cells were plated of each cell population in 2 replicates in each experiment. Mean (SEM) results from 2 experiments.

Cell-surface FLT3 expression in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell subsets. (A) FACS profiles from a representative mouse showing gating strategy for cell-surface FLT3 expression within LSKCD48+CD150−, LSKCD48+CD150+, and LSKCD48−CD150+ BM cells. Numbers indicate mean percentages of FLT3+ cells within each of the indicated gates, from 2 pools of BM cells, each from 3 mice. (B) Flt3 mRNA expression of single BM LSK subpopulations. Only cells that were Kit+ were included in analysis (86%-94% of all cells investigated). Data are expressed as mean (SD). For each population, a total of 176 cells were analyzed in 2 experiments. (C) Expression of different lineage programs in Flt3+ and Flt3− subsets of BM LSK populations. Cells were purified according to the indicated phenotypes and analyzed for expression of transcriptional programs for the GM (Csf3r, Mpo), MkE (Epor, Gata1, Vwf), and lymphoid (Ly; sterile Igh transcript, Rag1, Il7r) lineages. For a population to be classified as positive for a lineage-specific transcriptional program, transcripts of at least one of the aforementioned indicated lineage-specific genes should be detected. Mean (SD) results from 2 independent experiments with 88 single cells analyzed in each experiment. (D) Sorting strategy and purity analysis of LSKFLT3−, LSKFLT3lo, LSKFLT3int, and LSKFLT3hi cells isolated from 8- to 12-week-old WT mice. BM LSK cells were as indicated separated into 4 fractions on the basis of differential FLT3 expression. To the right is shown purity analysis for each of the fractions. (E) Mk potential of LSK cells separated on the basis of level of FLT3 expression. A total of 120 cells were plated of each cell population in each experiment. Mean (SD) results from 2 experiments. (F) Erythroid potential of LSK cells separated on the basis of levels of FLT3 expression. A total of 50 cells were plated of each cell population in 2 replicates in each experiment. Mean (SEM) results from 2 experiments.

Because these findings were compatible with the transcriptional initiation of Flt3 already in the MPP or even HSC compartment and cell-surface FLT3 expression in MPPs, we next investigated the Mk and E potentials of LSK cells, separated on the basis of different levels of FLT3 expression (Figure 1D). In agreement with previous studies,1,2 we found that LSKFLT3hi LMPPs (25% greatest FLT3-expressing cells within the LSK compartment) lacked detectable Mk and E potential, whereas a large fraction of LSKFLT3− cells produced colonies with mixed GM, Mk, and/or E potential (Figure 1E-F). LSKFLT3lo and in part also LSKFLT3int cells produced Mk- and E-containing colonies (Figure 1E-F), in agreement with previous studies in the fetal liver,2 suggesting that the MkE potential is gradually down-regulated with increasing cell surface FLT3 expression.

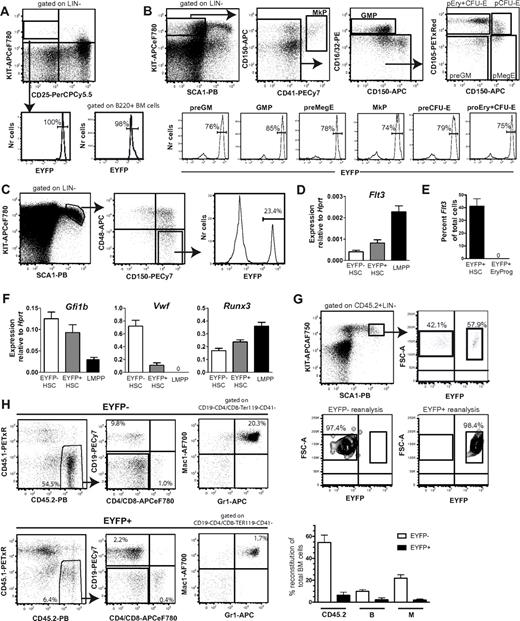

We next adapted cre-loxP fate mapping, in which mice expressing CRE recombinase under control of the mouse Flt3 promoter18 were crossed with mice with a loxP-flanked transcriptional termination sequence preceding the Eyfp gene, under control of the ubiquitous Rosa26 promoter.20 When intercrossed, cells expressing Flt3 and all their progeny (irrespectively of Flt3 expression) will express EYFP. As expected, on the basis of the importance of FLT3 in early lymphoid development,25 virtually all early thymic progenitors and BM B220+ B-cell progenitors were EYFP+ (Figure 2A), and as recently shown,21 also most preGM and GM progenitors (Figure 2B). Most notably, all stages of Mk and E progenitors also expressed EYFP at high frequencies (Figure 2B). Because Mk and E progenitors lack detectable FLT3 expression,21 these findings are compatible with MPPs expressing Flt3. In further support of this, a fraction (23%) of LSKCD150+CD48− cells were EYFP+, although in contrast to other progenitor subsets, most cells in the LSKCD150+CD48− HSC compartment were EYFP− (Figure 2C).

Flt3 fate mapping reveals that most erythroid and megakaryocyte progenitors are derived from Flt3-expressing progenitors. (A) EYFP expression in early thymic progenitors (LIN−CD25−KIT+; bottom left) and BM B220+ B-cell progenitors (bottom right) of Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ mice. (B-C) Representative FACS profiles of EYFP expression in myeloid progenitor subsets (B) or LSKCD150+CD48− HSCs (also gated as FLT3−; C) in the BM of Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ mice. Numbers in histograms are mean percentages from analysis of 3-6 mice. GMP indicates GM progenitor. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Flt3 mRNA expression in EYFP− LSKFLT3−CD150+ CD48− and EYFP+ LSKFLT3−CD150+CD48− HSCs and LSKFLT3hi LMPPs isolated from 3-week-old Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ mice. Mean (SEM) expression relative to Hprt, 50-100 cells/ well, 2-3 wells/mouse, 4 separate mice in total. (E) Single EYFP+ LSKFLT3−CD150+CD48− HSCs and EYFP+ Lin−SCA1+KIT−CD41−FcgR−CD150−CD105+ erythroid progenitors isolated from 4-week-old Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ mice were analyzed for Flt3 mRNA expression. Data are expressed as mean (SEM) percentage of single Kit+ cells. A total of 64 single EYFP+ HSCs were sorted in total, of which 63 cells were Kit+, and 24 single EYFP+ erythroid progenitors were sorted, of which 24 were Kit+. (F) Quantitative PCR analysis of VWF, Gfi1b, and Runx3 expression in EYFP+ LSKFLT3− CD150+CD48−, EYFP− LSKFLT3−CD150+CD48− HSCs, and LSKFLT3hi LMPPs isolated from 3-week-old Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ mice. Mean (SEM) expression relative to Hprt, 50-100 cells/well, 2-3 wells/mouse, 4 separate mice in total. (G) Two million BM cells from Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ CD45.2 mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipients. At 8 weeks after transplantation, donor-derived (CD45.2) LSKEYFP+ and LSKEYFP− cells were sorted for secondary transplantation. FACS profiles show representative distribution of LSKEYFP− and LSKEYFP+ cells in primary recipients and purity analysis after sorting. (H) Five thousand purified LSKEYFP− and LSKEYFP+ cells from primary recipients of Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ CD45.2+ BM cells were transplanted in competition with 300 000 WT CD45.1 BM cells into secondary recipients. At 6 months after transplantation, BM from recipients who underwent transplantation was analyzed for contribution of CD45.2+ cells toward the B-cell and myeloid cell lineages. To the left FACS profiles from representative mice. Percentages are mean values relative to total BM cells. To the right mean (SD) contribution in a total of 4-6 recipients each of transplanted LSKEYFP+ and LSKEYFP− cells toward total (CD45.2+), B (CD19+) and myeloid (Gr1+Mac1+) lineages at 6 months after transplantation.

Flt3 fate mapping reveals that most erythroid and megakaryocyte progenitors are derived from Flt3-expressing progenitors. (A) EYFP expression in early thymic progenitors (LIN−CD25−KIT+; bottom left) and BM B220+ B-cell progenitors (bottom right) of Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ mice. (B-C) Representative FACS profiles of EYFP expression in myeloid progenitor subsets (B) or LSKCD150+CD48− HSCs (also gated as FLT3−; C) in the BM of Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ mice. Numbers in histograms are mean percentages from analysis of 3-6 mice. GMP indicates GM progenitor. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Flt3 mRNA expression in EYFP− LSKFLT3−CD150+ CD48− and EYFP+ LSKFLT3−CD150+CD48− HSCs and LSKFLT3hi LMPPs isolated from 3-week-old Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ mice. Mean (SEM) expression relative to Hprt, 50-100 cells/ well, 2-3 wells/mouse, 4 separate mice in total. (E) Single EYFP+ LSKFLT3−CD150+CD48− HSCs and EYFP+ Lin−SCA1+KIT−CD41−FcgR−CD150−CD105+ erythroid progenitors isolated from 4-week-old Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ mice were analyzed for Flt3 mRNA expression. Data are expressed as mean (SEM) percentage of single Kit+ cells. A total of 64 single EYFP+ HSCs were sorted in total, of which 63 cells were Kit+, and 24 single EYFP+ erythroid progenitors were sorted, of which 24 were Kit+. (F) Quantitative PCR analysis of VWF, Gfi1b, and Runx3 expression in EYFP+ LSKFLT3− CD150+CD48−, EYFP− LSKFLT3−CD150+CD48− HSCs, and LSKFLT3hi LMPPs isolated from 3-week-old Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ mice. Mean (SEM) expression relative to Hprt, 50-100 cells/well, 2-3 wells/mouse, 4 separate mice in total. (G) Two million BM cells from Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ CD45.2 mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipients. At 8 weeks after transplantation, donor-derived (CD45.2) LSKEYFP+ and LSKEYFP− cells were sorted for secondary transplantation. FACS profiles show representative distribution of LSKEYFP− and LSKEYFP+ cells in primary recipients and purity analysis after sorting. (H) Five thousand purified LSKEYFP− and LSKEYFP+ cells from primary recipients of Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ CD45.2+ BM cells were transplanted in competition with 300 000 WT CD45.1 BM cells into secondary recipients. At 6 months after transplantation, BM from recipients who underwent transplantation was analyzed for contribution of CD45.2+ cells toward the B-cell and myeloid cell lineages. To the left FACS profiles from representative mice. Percentages are mean values relative to total BM cells. To the right mean (SD) contribution in a total of 4-6 recipients each of transplanted LSKEYFP+ and LSKEYFP− cells toward total (CD45.2+), B (CD19+) and myeloid (Gr1+Mac1+) lineages at 6 months after transplantation.

Because the Cre transgene was inserted into the first exon of the Flt3 locus in Flt3-Cre mice19 we could not easily distinguish between transcriptional and genomic expression of Cre in purified EYFP+ HSCs. However, in agreement with EYFP expression in a fraction of the LSKCD150+CD48− HSC compartment, quantitative PCR analysis demonstrated expression of Flt3 mRNA in LSKCD150+CD48−EYFP+ cells that was greater than in LSKCD150+CD48−EYFP− cells and, as expected, lower than in LMPPs that express high levels of cell-surface FLT3 (Figure 2D). Furthermore, single-cell PCR analysis detected Flt3 mRNA expression in almost one-half of EYFP+ LSKFLT3−CD150+CD48− HSCs, in contrast to EYFP+ erythroid progenitors, which lacked Flt3 mRNA expression as reported previously (Figure 2E).21 These data demonstrate that unlike detectable FLT3 cell-surface protein expression, Flt3 transcriptional activity already initiates in the phenotypic pluripotent HSC compartment, and in agreement with being progeny of HSCs/MPPs, although not expressing Flt3 themselves, MkE progenitors sustain EYFP expression when Flt3-Cre fate mapping is applied.

Notably, the expression of the MkE-related genes VWF and Gfi1b was down-regulated in EYFP+ compared with EYFP− LSKCD150+CD48− cells, whereas expression of Runx3, implied in lymphoid development,26 was increased (Figure 2F). These findings suggest that Flt3-Cre/EYFP expression marks cells that have initiated a lineage priming (down-regulation of MkE and up-regulation of lymphoid-related transcripts), preparing cells for transition into a LMPP-like state.

Finally, to investigate whether the expression of Flt3 mRNA in a fraction of LSKCD150+CD48− cells reflects that Flt3 transcription already initiates in functionally defined HSCs, irradiated mice underwent transplantation with Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ unfractionated BM cells. After 8 weeks, a mean of 58% of donor-derived LSK cells were EYFP+, and LSKEYFP− and LSKEYFP+ cells were purified from reconstituted mice and transplanted competitively into secondary recipients to assess for functional HSC activity (Figure 2G). After 6 months, only LSKEYFP− cells contributed robustly to the short-lived myeloid lineage, whereas LSKEYFP+ cells gave much lower overall and in particular myeloid reconstitution (Figure 2H), suggesting that few if any self-renewing HSCs express Flt3 in steady state and on cell cycling after transplantation.

Herein, single-cell mapping of Flt3 mRNA expression and Flt3-Cre fate mapping demonstrated that Flt3 expression initiates in fully multipotent mouse progenitors, because not only lymphoid and GM progenitors but also most Mk and E restricted progenitors were EYFP+ in Flt3-Cretg/+R26REYFP/+ mice, despite lacking cell-surface FLT3 and Flt3 mRNA expression. Thus, these data demonstrate that Flt3-driven Cre protein expression and function precedes FLT3 protein expression in multipotent progenitors.

Unlike in LSKFLT3hi LMPPs, Flt3 is coexpressed at the single-cell level with MkE transcriptional programs in MPPs, and a fraction of LSK cells with low and intermediate (but not high) levels of cell surface FLT3 sustain MkE potential. In agreement with this, stem cell reconstitution patterns were most compatible, with Flt3 expression being activated in the transition from self-renewing HSCs to MPPs, perhaps as a result of cell-cycle activation.

The present studies also reinforce the existence of GM-lymphoid restricted LSKFLT3hi LMPPs, establishing that MkE transcriptional priming and potential is gradually down-regulated in MPPs with increasing FLT3 expression, underscoring the importance of defining LMPPs on the basis of high FLT3 expression1,2 and/or alternative markers.6-8

Our findings suggest that in mouse knock-in models,17 Flt3-itd will be activated already in fully multipotent progenitors. This finding is of considerable importance because FLT3 expression in humans has been suggested to initiate at the multipotent stem/progenitor stage,14,15 although it is difficult to extrapolate from mouse to human because human HSCs have yet to be as stringently defined as in mice.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Denise Jelfs, Caroline Barnwell, Jordan Tanner, Dominik Woznica, Fred Dickinson, and Theresa Furey (University of Oxford) for expert animal support; Drs Thomas Boehm and Conrad C. Bleul (Max Planck Institute, Freiburg, Germany) for providing the Flt3-Cre mice; Dr Shankar Srinivas (University of Oxford) for the R26R-EYFP mice; and Sally-Anne Clark (University of Oxford) for help with cell sorting.

This work was supported by grants from EU-FP7 STEMEXPAND and EU-FP7 EuroSyStem Integrated project and a program grant from the Medical Research Council, United Kingdom, to S.E.W.J. A.H. was funded by grants from Crafoord foundation, Swedish Society of Medicine, and Swedish Cancer foundation. S.D. was funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia.

Authorship

Contribution: N.B-V. and S.E.W.J. designed and conceptualized the overall research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; N.B.-V. performed the transplantations, phenotypic FACS analysis, sorting, and cell-culture experiments; P.W. S.D., M.L., and T.B.-J. performed FACS analysis of stem/progenitors and peripheral blood; P.W., and M.L., and H.F. performed cell sorting; P.W. and A.H. performed the gene expression analysis; and S.L. performed MkE assays.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sten Eirik W. Jacobsen, Haematopoietic Stem Cell Laboratory, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford, John Radcliffe Hospital, Headington, Oxford OX3 9DS, United Kingdom; e-mail: sten.jacobsen@imm.ox.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal