Abstract

Abstract 4338

Assessment of TAT for blood ordering has emerged as an important benchmark for the OR and TS in order to improve blood transfusion support for surgical patients. Standards for TAT in the OR exist for anatomical (e.g., frozen sections) and clinical pathology (e.g., arterial blood gases), but not for TS.

Call-slips from April 1, 2011 through April 27, 2011 and June 1, 2011 through June 30, 2011 were evaluated retrospectively for RBC TAT. The time for completion of the order was evaluated using the initial call-slip time stamp as the start time and the time of pneumatic tube send-off as the end time. Those cases that did not have an initial time stamp were excluded, as were cases with > 4 RBC units ordered per call-slip. Sixty-eight cases that demonstrated greater than the 20 min specified in our TAT policy were evaluated for readily identifiable contributing factors. Nineteen cases had incomplete diagnostic testing and were excluded from analysis. The remaining 49 (14%) of 346 cases had no definite readily identifiable contributing factors for product delay including analysis of antibody screen results, patient special needs, and any pending TS work-up. A total of 346 cases met the inclusion criteria for the study. Continuous variables were compared with a student's t-test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.0008 to account for multiple comparisons.

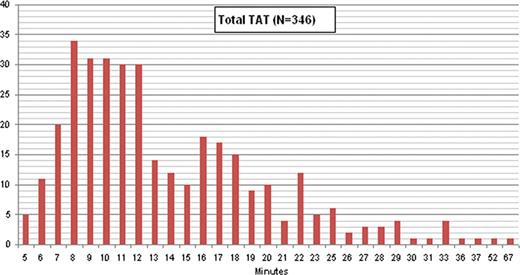

A mean 2.4 ± 0.9 RBC units (range 1–4 units) per order had a mean TAT of 14 min (median 12; SD 7.2). Two hundred ninety-seven of 346 orders (86%) complied with our ≤ 20-min TAT policy. TAT for the 90th, 75th, 25th, and 10th percentiles was 22, 17, 9, and 7 min respectively The mean TAT increased from 12 min for 1 unit orders to 18 min (p = 0.0005) for 4 unit orders (Table). Eighty-two percent of 346 orders were received during the 0700–1259 and 1300–1859 time segments (0700–1259 (39%); 1300–1859 (43%); 1900–0059 (12%); 0100–0659 (6%)). TAT was not different for the four time segments evaluated, with a mean TAT of 14 min for the 0700–1259, 1300–1859, and 1900–0059 time segments and 17 min for the 0100–0659 time segment (p = 0.04 comparing 0100–0659 to 0700–1259; not significant for multiple comparisons). The distribution of TAT is illustrated in the Figure showing a ‘tail’ of 28 (8%) of 346 cases with ≥ 25 min TAT.

| RBC Orders . | # Cases . | Mean TAT . | Median TAT . | SD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 unit | 26 | 12 min | 11 min | 5.7 |

| 2 unit | 242 | 13 min | 11 min | 6.7 |

| 3 unit | 5 | 17 min | 13 min | 8.1 |

| 4 unit | 73 | 18 min | 17 min | 7.6 |

| All | 346 | 14 min | 12 min | 7.2 |

| RBC Orders . | # Cases . | Mean TAT . | Median TAT . | SD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 unit | 26 | 12 min | 11 min | 5.7 |

| 2 unit | 242 | 13 min | 11 min | 6.7 |

| 3 unit | 5 | 17 min | 13 min | 8.1 |

| 4 unit | 73 | 18 min | 17 min | 7.6 |

| All | 346 | 14 min | 12 min | 7.2 |

Our results compare favorably to the previously published intraoperative TAT by Novis et al. (Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002;126:909–916). While this cited study evaluated emergent rather than routine blood requests and included all numbers of unit orders, useful reference TAT comparisons can still be made. We found an overall median intraoperative TAT of 12 minutes compared to Novis et al. overall median TAT of 34 and 14 minutes for the fastest performing 10% of study participants. Our study demonstrates that TAT assessment is affected by factors external to the TS such as incomplete diagnostic testing (e.g. missing type and screen and/or ABO confirmation testing) as well as other case specific variables (e.g., verbal requests for sequential partial orders over a prolonged time interval). In particular, the ‘tail’ in TAT for the 8% of samples (25 to 60 min) beyond our TAT goal of 20 min needs to be addressed so that OR and hospital quality departments understand that limitations in TAT reflect variables both internal and external to the TS.

Criteria for benchmarking RBC product intraoperative TAT currently do not exist. Contributing factors to TAT are complex and must be characterized further so that improvement in performance can occur. Accurate inter-institutional TAT comparisons are also important to better establish benchmarking standards for this quality indicator. By using this data workflow procedures may be optimized, appropriate staffing levels can be achieved, and appropriate blood ordering practices can be implemented.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal