Abstract

Abstract 4103

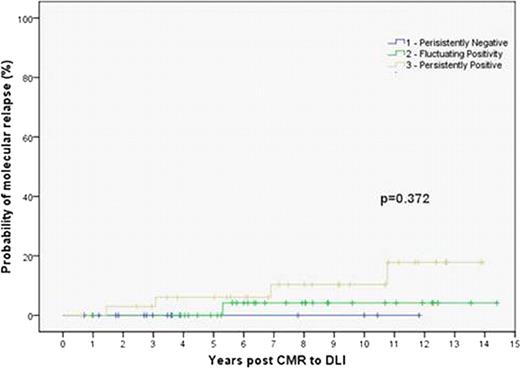

The probability of molecular relapse following complete molecular remission is low and not significantly different between those who are persistently negative, fluctuating low-level positive or persistently positive.

The probability of molecular relapse following complete molecular remission is low and not significantly different between those who are persistently negative, fluctuating low-level positive or persistently positive.

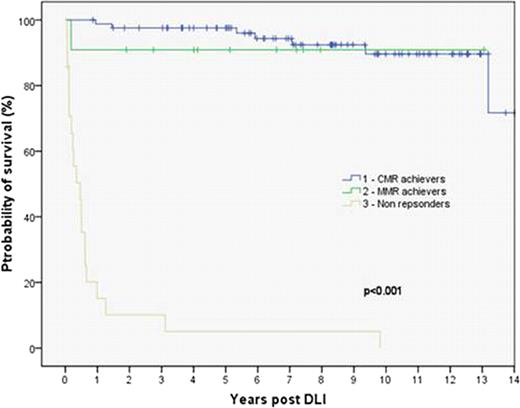

Patients who achieve a major molecular remission but not a complete molecular remission have non-inferior survival to those who do achieve a complete molecular remission, which is significantly better than those who do not achieve either of these.

Patients who achieve a major molecular remission but not a complete molecular remission have non-inferior survival to those who do achieve a complete molecular remission, which is significantly better than those who do not achieve either of these.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal