Abstract

Kit regulation of mast cell proliferation and differentiation has been intimately linked to the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase (PI3K). The activating D816V mutation of Kit, seen in the majority of mastocytosis patients, causes a robust activation of PI3K signals. However, whether increased PI3K signaling in mast cells is a key element for their in vivo hyperplasia remains unknown. Here we report that dysregulation of PI3K signaling in mice by deletion of the phosphatase and tensin homolog (Pten) gene (which regulates the levels of the PI3K product, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate) caused mast cell hyperplasia and increased numbers in various organs. Selective deletion of Pten in the mast cell compartment revealed that the hyperplasia was intrinsic to the mast cell. Enhanced STAT5 phosphorylation and increased expression of survival factors, such as Bcl-XL, were observed in PTEN-deficient mast cells, and these were further enhanced by stem cell factor stimulation. Mice carrying PTEN-deficient mast cells also showed increased hypersensitivity as well as increased vascular permeability. Thus, Pten deletion in the mast cell compartment results in a mast cell proliferative phenotype in mice, demonstrating that dysregulation of PI3K signals is vital to the observed mast cell hyperplasia.

Introduction

Mast cells (MCs) are innate immune cells that also serve to amplify adaptive immunity.1 They are best known for their role as effector cells in allergic disease,2 but there is considerable evidence of a beneficial role for these cells in host defense and immune regulation.3 In various pathologic circumstances, MC numbers can be increased because of hyperplasia or neoplastic transformation.4,5 Mastocytosis is a term used to collectively describe MC hyperplasia/neoplasia in one or more organs. Systemic mastocytosis normally involves one or more visceral organs with or without skin involvement. The majority of patients with mastocytosis carry a somatic mutation in the Kit proto-oncogene, the receptor for SCF that is central to MC proliferation and differentiation. Substitution of D for V at position 816 in the kinase domain of the receptor results in constitutive (SCF-independent) activation of Kit and enhanced MC proliferation.6

It is well known that signals generated by SCF engagement of Kit are highly dependent on the activity of phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase (PI3K).7-10 In addition, PI3K activity is also increased by the D816V mutation of Kit.9 Proliferation of murine MCs is also partly dependent on IL-3 and its receptor (IL-3R).11,12 Human intestinal MCs also express functional IL-3R, and IL-3 stimulation causes enhanced growth rates and effector responses.13 Interestingly, IL-3R activity and its role in regulating proliferative responses are also tightly coupled to the activation of PI3K.14 In addition, STAT5 is also important to the transcriptional activity induced by the IL-3R and c-Kit, and STAT5-PI3K-Akt signals are known to be essential for Kit D816V-mediated growth and survival.8,14,15

PI3K generates the lipid second messenger phosphatidylinositol trisphosphate (PIP3) by phosphorylating phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI4,5-P2) in the 3′ position. PIP3 is a key intracellular regulator that promotes the appropriate localization of many signaling proteins and enhances their activity by binding to various structural motifs on these proteins, such as the pleckstrin homology domain. Previous in vitro studies have shown that increased cellular levels of PIP3 caused an abnormal constitutive secretion of certain MC cytokines, increased MC proliferation, and enhanced the overall stimulated MC effector responses.16 Whether dysregulation of PIP3 levels might result in MC proliferative diseases in vivo has not been explored.

The phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) controls the levels of intracellular PIP3 by dephosphorylating PIP3 in the 3′ position. Herein, we explored whether in vivo dysregulation of PIP3 levels in MCs through genetic deletion of Pten (using mouse models in which Pten was inducibly or conditionally deleted) would lead to an MC proliferative disease. We found that the inducible deletion of Pten in all tissues or its conditional deletion in the MC compartment caused a MC proliferative-like disease with features of systemic mastocytosis.4,6,17 PTEN-deficient MCs had markedly enhanced responses to SCF and IL-3. Akt and STAT5 phosphorylation as well as the expression of survival genes, such as Bcl-XL, were increased. The findings demonstrate that Pten deletion in the MC compartment drives a MC proliferative-like disease with some mechanistic and pathologic features of systemic mastocytosis.

Methods

Mice and histology

All mice were used in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases–approved animal study (proposal A010-04-03). ROSACreEr mice (B6;129-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(cre/Esr1)Nat/J) expressing an inducible form of Cre recombinase (targeted to the nucleus by the binding of tamoxifen to a modified form of the estrogen receptor), Ptenloxp/loxp mice (C;129S4-Ptentm1Hwu/J), and the MC-deficient strain KitW-sh/W-sh (B6.Cg-KitW-sh/HNihrJaeBsmJ) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. The ROSACreEr and PTENloxp/loxp mice were crossed to generate the tamoxifen-inducible PTEN-deficient mouse (Pten−/−CreEr), herein referred to as Pten−/− mice (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The genotype of obtained mice was determined by PCR analysis. Cre recombinase was targeted to the nucleus with 1 mg of tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in corn oil, injected intraperitoneally into 4-week-old male mice. Corn oil–injected mice were used as controls. Four weeks after injection, the mice were killed for analysis. The MC-specific Cre mice (FcϵRIβCre) were generated by homologous recombination of Cre-GFP flanked by FcϵRI β-chain homologous sequence inserted between exons 1 and 2 of the FcϵRI β-chain, and correct integration was verfied by Southern blot (supplemental Figure 2). These mice were subsequently crossed with Ptenloxp/loxp (referred to as Ptenfl/fl). GFP expression was not observed in MCs of these mice, and sequencing of the genomic insertion showed a mutation in the GFP sequence. Genotype of obtained mice (Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre), which were either homozygous (FcϵRIβCre+/+) or heterozygous (FcϵRIβCre+/wt) for Cre integration, was determined by PCR analysis. Analysis of PTEN expression in splenocytes revealed no alterations and blood counts as well as liver weight revealed no significant difference between Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre and Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre mice, albeit the latter showed a slight but significant reduction in spleen weight (supplemental Figure 3). PTEN expression in lymphoid organs was not different except for the spleen where Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre showed reduced expression (supplemental Figure 4A). Analysis of PTEN expression in CD4+or CD8+ T cells, CD19+ B cells, and CD11b+ myeloid cells, derived from the spleen of Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre mice or their WT counterparts, revealed no differences in PTEN expression (supplemental Figure 4B). As shown in supplemental Figure 5, CD8+ T cells in the lymph nodes and spleen showed a trend toward reduced numbers (albeit not significant). B cells as well as myeloid/monocytic cell numbers did not differ significantly (supplemental Figure 5).

Cell cultures and adoptive transfer of MCs to MC-deficient mice

Bone marrow–derived MCs (BMMCs) were generated from the femurs and tibias of mice after culturing in the presence of IL-3 and SCF for 4 to 6 weeks as previously described.18 Where indicated, cells were grown in IL-3 alone, and SCF was added as the stimulus as indicated. Peritoneal cells were harvested from killed animals by lavage of the peritoneum using 5 mL of PBS injected into the peritoneal cavity. Cells were cultured in the aforementioned medium to obtain an expanded population of peritoneal-derived MCs (PDMCs). Cells were stained for cell surface expression of Kit and/or FcϵRI as indicated. Experiments were conducted when MC cultures showed > 95% purity.

To reconstitute KitW-sh/Wa-sh mice with MCs, BMMCs derived from C57BL/6 mice were grown in vitro and were subsequently injected intravenously into MC-deficient mice as previously described.3 In some experiments, BMMCs from a mixed background (129Sv × C57BL/6 (N2)) were used. For histology, recovered tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours and embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with 0.1% toluidine blue (eosin counterstaining) or H&E staining. MCs were quantified per millimeter squared.

Antibodies and reagents

Mouse anti–DNP mAb was purified from culture supernatants of the H1-DNP-ϵ-26.82 hybridoma.19 PE-MAR-1 (anti-FcϵRI) was obtained from eBioscience. APC–anti-Kit, and 2.4G2 (rat anti–mouse FcγRII/RIII) were purchased from BD Biosciences. mAb to PTEN was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Polyclonal antibodies (pAb) or mAb to Akt (pAb), phospho AKT (T308) (mAb), STAT5 (mAb), Bcl-XL (pAb), and Bcl-2 (pAb) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibody to pSTAT5 (pAb) was from Zymed, and antibody to β-actin (mAb) was from Novus Biologicals. The secondary antibodies used were Alexa-680–labeled goat-anti–rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) and IRDye-800–labeled goat-anti–mouse IgG (Rockland Immunochemicals). Cell culture medium (DMEM and RPMI 1640) and other described reagents were obtained from Invitrogen, with the exception of 2-mercaptoethanol and streptavidin (Sigma-Aldrich). Murine IL-3 and SCF were obtained from PeproTech.

Cell activation, lysis, and Western blot analysis

BMMCs were cultured in medium containing IL-3 in the absence of SCF overnight before sensitization with 2 μg/mL of IgE in Tyrode buffer devoid of any cytokine for 2 hours and subsequently stimulated with the indicated concentrations of DNP-HSA (Ag). Cells (stimulated or not) were washed once with ice-cold PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer (10mM NaH2PO4, 50mM NaCl, 50mM NaF, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.05% NaN3, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton, 1mM Na3VO4) for 30 minutes. Lysates were cleared of insoluble material by centrifugation (4°C) at 12 000g for 10 minutes. Proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE before transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with a blocking buffer obtained from Li-Cor Biosciences for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary and fluorescent secondary antibodies were used according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by detection with the Li-Cor Odyssey system.

Degranulation and cytokine production

Cells were sensitized (1-3 × 106 per sample) with 2 μg/mL IgE per 106 cells for 30 minutes and stimulated with the indicated concentration of Ag or alternatively costimulated with SCF (10 ng/mL) in 0.05% BSA-Tyrode buffer for 30 minutes for degranulation. Degranulation was measured as previously described.20 For cytokine production, BMMCs were stimulated in serum-, SCF-, and IL-3–free medium for 4 hours. In the indicated experiments, SCF (10 ng/mL) was used to costimulate in the presence of Ag. TNF, IL-3, and IL-6 were measured from collected supernatants by specific ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Flow cytometry and proliferation assays

Red blood cells were lysed with ACK lysing buffer (Lonza Walkersville) when needed, and the indicated cell surface markers were detected using specific fluoresceinated antibodies after incubation with 2.4G2 (CD16/32 FcγR blocking antibody). FACS analysis was done with a FACSCaliber (BD Biosciences) and Cell Quest 6.0 software. Analysis was done with FlowJo 9.33 software (TreeStar). For proliferation assays, CFSE staining was performed according to manual instruction. Flow cytometric analysis was performed after 3 days of culture. For thymidine incorporation studies, cells (1 × 104) of the indicated genotype were cultured with 1 mCi 3H-thymidine for 12 hours, and incorporated radioactivity was measured by scintillation counting.

Anaphylaxis and arthritis models

To determine the effect of MC hyperplasia on an inflammatory responses, the previously described KRN model of inflammatory arthritis was used.21 Decalcified ankles were processed for paraffin sectioning and stained with either hematoxylin and eosin or toluidine blue.

For passive systemic anaphylaxis, mice were sensitized with 3 μg of DNP-specific IgE by retro-orbital injection and implantable electronic ID transponders (Bio Medic Data Systems) were injected subcutaneously. After 24 hours, mice were challenged with 500 μg of antigen (DNP36-HSA) by retro-orbital injection. Changes in temperature were monitored by an IPTT scanner (BMDS) for each individual mouse. Passive cutaneous anaphylaxis was essentially as previously described,22 with the modification that 35 μg of compound 48/80 (C48/80) in a 20-μL volume was used for challenge.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted with at least 3 to 5 individual BMMC cultures. In vitro experiments were analyzed for statistical significance by a Student t test. In vivo experiments were analyzed for statistical significance using ANOVA. Prism software (GraphPad Software) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

PTEN deficiency enhances early MC proliferation and markedly increases their numbers in peripheral tissues and in the circulation

We developed a mouse model where PTEN deletion could be induced (Ptenloxp/loxp-CreEr). Tamoxifen treatment of these mice (referred to as Pten−/−) resulted in a reduction of > 95% of PTEN protein expression in total splenocytes or in BMMCs (supplemental Figure 1A) but did not affect FcϵRI expression on BMMCs (supplemental Figure 1B). Because PTEN deficiency was previously demonstrated to alter cell growth,16,23 we first evaluated the effect of PTEN deficiency on MC proliferation and development. As shown in Figure 1A, the proliferation of PTEN-deficient cells differed significantly from that of the control BMMCs as early as day 7 of culture. This difference was further augmented by day 13 of culture (Figure 1A). The proportion of Kit+FcϵRI+ MCs also differed at early stages in culture, suggesting increased numbers of MC progenitors and/or a more rapid differentiation of MCs (Figure 1B). At day 23, PTEN-deficient MCs showed only minor differences to control MCs in proliferation (Figure 1A); however, thymidine incorporation studies demonstrated that MC proliferation was still enhanced at day 28 of culture (Figure 1C). The proliferation was more pronounced when IgE was added to the culture, consistent with a role for IgE in MC survival and growth.24-26 The difference in proliferation was partly masked by stimulation of MCs with SCF or IgE in combination with SCF, but total thymidine incorporation was markedly increased on SCF stimulation.

PTEN deficiency enhances BMMC proliferation and differentiation. (A) Bone marrow cells from WT (red) or PTEN-null mice (blue) were stained with CFSE and analyzed for cell division on day 7, day 13, and day 23 of culture. Fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. One representative of 4 experiments is shown. (B) Percentage of FcϵRI and Kit double-positive cells in bone marrow cell cultures of the indicated genotype over time. Cells (1 × 105 cells) were labeled with PE-MAR-1 (anti-FcϵRI) and APC–anti-Kit. Mean fluorescence intensity was determined by flow cytometry. (C) BMMCs (1 × 104) of the indicated genotypes were incubated with 3H-thymidine (1 mCi) and IgE, SCF, or IgE plus SCF. After 12 hours, the amount of incorporated thymidine was determined. (B-C) A minimum of 4 experiments were conducted.

PTEN deficiency enhances BMMC proliferation and differentiation. (A) Bone marrow cells from WT (red) or PTEN-null mice (blue) were stained with CFSE and analyzed for cell division on day 7, day 13, and day 23 of culture. Fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. One representative of 4 experiments is shown. (B) Percentage of FcϵRI and Kit double-positive cells in bone marrow cell cultures of the indicated genotype over time. Cells (1 × 105 cells) were labeled with PE-MAR-1 (anti-FcϵRI) and APC–anti-Kit. Mean fluorescence intensity was determined by flow cytometry. (C) BMMCs (1 × 104) of the indicated genotypes were incubated with 3H-thymidine (1 mCi) and IgE, SCF, or IgE plus SCF. After 12 hours, the amount of incorporated thymidine was determined. (B-C) A minimum of 4 experiments were conducted.

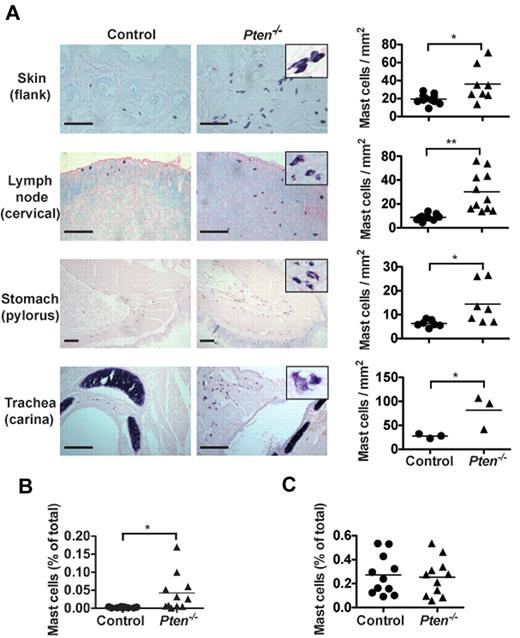

The enhanced proliferation of PTEN-deficient MCs suggested a possible increase of their numbers in Pten−/− mice. As seen in Figure 2A, Pten−/− mice had higher numbers of MCs in the skin, stomach, trachea, and lymph nodes compared with control mice. The MCs in PTEN-deficient mice frequently appeared clustered, and some showed partial degranulation and/or spindle-shaped morphology (Figure 2A inset). Quantitation of MC numbers in the lymph nodes showed an almost 3-fold increase in MC numbers with a concomitant increase in the proportion of CD25+ MCs (supplemental Figure 6A). In contrast, no accumulation of basophils was observed in most tissues (supplemental Figure 6B). A slight increase in basophils was seen in the peritoneum of these mice where injection with tamoxifen or the solvent (oil) elicited increased numbers of basophils. Moreover, some MCs could be found in the blood of these mice, whereas they were completely absent in control mice (Figure 2B). However, we found no significant difference in the numbers of Kit+FcϵRI+ cells in the bone marrow (Figure 2C). Collectively, these findings demonstrated that the absence of PTEN caused enhanced MC proliferation in peripheral tissues, which leads to their increased numbers in vivo and their presence in the blood.

Pten−/− mice have circulating MCs and increased MC numbers in tissues. (A) Tissue samples of the indicated tissues from 8-week-old mice were fixed with 4% formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sections were stained with toluidine blue. MCs from Pten−/− mice showed spindle-shaped and partially degranulated phenotypes (inset). MC numbers per millimeter squared (graphs) were determined by counting blinded samples from individual mice. Images were visualized on a Leica DM LB2 microscope using a 20× (0.40 NA) objective for dry mounted slides. Image capture was with a QImacong Micro Publisher 3.3 RTV camera using QCapture 2.7.3 software. Image analysis was with ImageJ 1.45 (National Institutes of Health). Statistical analysis was by an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test: *P < .05; **P < .01. Scale bar represents 100 μm. (B-C) Percentage of FcϵRI and Kit-positive cells was analyzed in peripheral blood (B) and in the bone marrow (C) of individual mice with the indicated genotype. Cells (1 × 105) were labeled with PE-MAR-1 (anti-FcϵRI) and APC–anti-Kit. Mean fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry (n = 15 for peripheral blood cells; 6 of 15 mice had circulating MCs; n = 11 for bone marrow cells). For peripheral blood cell counts, 0.025% of double = positive cells was set as a threshold for background. (B-C) A minimum of 4 individual experiments were conducted.

Pten−/− mice have circulating MCs and increased MC numbers in tissues. (A) Tissue samples of the indicated tissues from 8-week-old mice were fixed with 4% formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sections were stained with toluidine blue. MCs from Pten−/− mice showed spindle-shaped and partially degranulated phenotypes (inset). MC numbers per millimeter squared (graphs) were determined by counting blinded samples from individual mice. Images were visualized on a Leica DM LB2 microscope using a 20× (0.40 NA) objective for dry mounted slides. Image capture was with a QImacong Micro Publisher 3.3 RTV camera using QCapture 2.7.3 software. Image analysis was with ImageJ 1.45 (National Institutes of Health). Statistical analysis was by an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test: *P < .05; **P < .01. Scale bar represents 100 μm. (B-C) Percentage of FcϵRI and Kit-positive cells was analyzed in peripheral blood (B) and in the bone marrow (C) of individual mice with the indicated genotype. Cells (1 × 105) were labeled with PE-MAR-1 (anti-FcϵRI) and APC–anti-Kit. Mean fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry (n = 15 for peripheral blood cells; 6 of 15 mice had circulating MCs; n = 11 for bone marrow cells). For peripheral blood cell counts, 0.025% of double = positive cells was set as a threshold for background. (B-C) A minimum of 4 individual experiments were conducted.

PTEN-deficient MCs overcome MHC restriction and selective deletion of Pten in MCs also results in increased numbers in vivo

To address whether the enhancement in MC proliferation and the increase in MC numbers in vivo is a consequence of an altered environment (thus possibly influencing MC proliferation and differentiation) or was intrinsic to the MC, we first tested whether BMMCs derived from the Pten−/− mice (B6.129Sv) could overcome MHC restriction by adoptive transfer into MC deficient KitW-sh/W-sh mice (C57BL/6). It is well known that hyperplasia or neoplasia can surmount the barriers presented by MHC restriction27 ; thus, we reasoned that BMMCs derived from B6.129Sv Pten−/− mice could have altered intrinsic characteristics that might allow escape from immune surveillance. As shown in supplemental Figure 7, control BMMCs from C57BL/6 mice and BMMCs from Pten−/− mice (B6.129Sv) successfully engrafted in C57BL/6 KitW-sh/W-sh mice, whereas control BMMCs from mixed background (B6.129Sv) mice did not. These findings demonstrated that BMMCs from Pten−/− mice were intrinsically different from those of WT mice allowing allogenic engraftment.

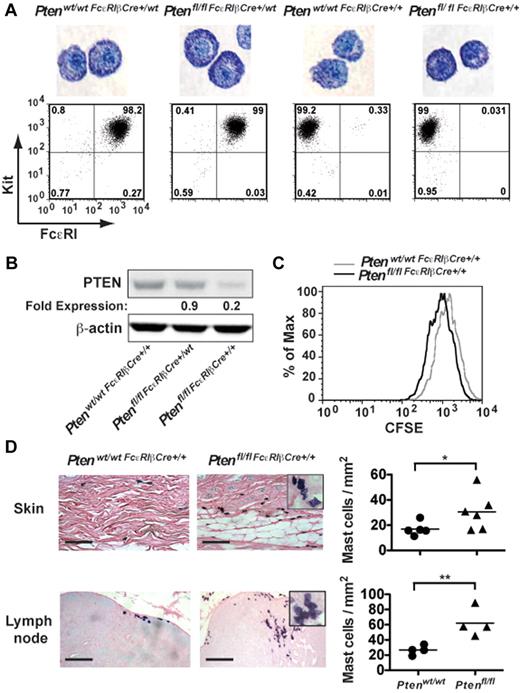

Because the aforementioned experiments did not allow a comparison of the effect of PTEN deficiency on MC numbers in vivo (because control MCs of mixed background did not engraft), we generated mice (Ptenfl/fl-FcϵRIβCre) in which Pten was specifically disrupted in MCs through expression of Cre recombinase driven by the FcϵRIβ promoter, which is selectively expressed in MCs and basophils. To assess the efficiency of Pten deletion, peritoneal cells from 4-week-old mice were cultured with IL-3 and SCF for 4 weeks to generate PDMCs, which are highly granulated relative to BMMCs, and expression of FcϵRI and PTEN were analyzed (Figure 3A-B). Cells derived from young Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/wt mice expressing Cre recombinase from a single FcϵRIβ allele showed almost normal expression of PTEN (∼ 85% of control mice) and no significant difference in FcϵRI expression (Figure 3A-B), suggesting the poor expression of Cre recombinase from a single allele. In contrast, whereas expression of FcϵRI was totally abrogated in mice where Cre recombinase was expressed from both FcϵRIβ alleles (Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/+), expression of PTEN ranged from 10% to 20% of normal depending on the mouse analyzed (Figure 3B). Similar results were obtained in BMMCs, and staining of BMMCs with toluidine blue showed no significant difference in MC maturation among the 4 genotypes analyzed (data not shown).

Tissue-specific deletion of Pten demonstrates altered proliferation and increased MC numbers in vivo. (A) PDMCs (1 × 105 cells) from the indicated genotypes (age of mice, 16-24 weeks) were stained with toluidine blue. The controls, Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/wt, and Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice were heterozygotes or homozygotes, respectively, for Cre expression at the FcϵRIβ locus and did not carry floxed Pten alleles. Cell surface expression of FcϵRI and Kit in PDMCs of indicated genotypes was determined. Cells (1 × 105 cells) were incubated with PE-MAR-1 (anti-FcϵRI) and APC–anti-Kit. The mean fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. One representative of 3 individual experiments is shown. (B) PDMCs (5 × 105 cells) were lysed in RIPA buffer. PTEN expression was determined by immunoblot with a monoclonal antibody to PTEN. β-actin was used as loading control. (C) Cell proliferation was measured by CFSE staining. Mean fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. (B-C) A minimum of 3 individual experiments were conducted. (D) Tissue samples were fixed with 4% formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sections stained with toluidine blue. MCs per millimeter squared was determined by direct counts of blinded samples. Statistical analysis was by an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test: *P < .05; **P < .01. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

Tissue-specific deletion of Pten demonstrates altered proliferation and increased MC numbers in vivo. (A) PDMCs (1 × 105 cells) from the indicated genotypes (age of mice, 16-24 weeks) were stained with toluidine blue. The controls, Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/wt, and Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice were heterozygotes or homozygotes, respectively, for Cre expression at the FcϵRIβ locus and did not carry floxed Pten alleles. Cell surface expression of FcϵRI and Kit in PDMCs of indicated genotypes was determined. Cells (1 × 105 cells) were incubated with PE-MAR-1 (anti-FcϵRI) and APC–anti-Kit. The mean fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. One representative of 3 individual experiments is shown. (B) PDMCs (5 × 105 cells) were lysed in RIPA buffer. PTEN expression was determined by immunoblot with a monoclonal antibody to PTEN. β-actin was used as loading control. (C) Cell proliferation was measured by CFSE staining. Mean fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. (B-C) A minimum of 3 individual experiments were conducted. (D) Tissue samples were fixed with 4% formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sections stained with toluidine blue. MCs per millimeter squared was determined by direct counts of blinded samples. Statistical analysis was by an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test: *P < .05; **P < .01. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

Analysis of the proliferation of MCs derived from the Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/+ mouse showed that the proliferation of MCs was markedly increased on PTEN deletion relative to control mice (Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/+, Figure 3C). In vivo analysis revealed increased numbers of MCs in the skin and lymph nodes (Figure 3D), and circulating tryptase levels were elevated in these mice (supplemental Figure 8A). Moreover, similar to the universal deletion of Pten (Pten−/− mice), MCs were found in clusters, and many showed evidence of partial degranulation and/or spindle-shaped morphology (Figure 3D inset).

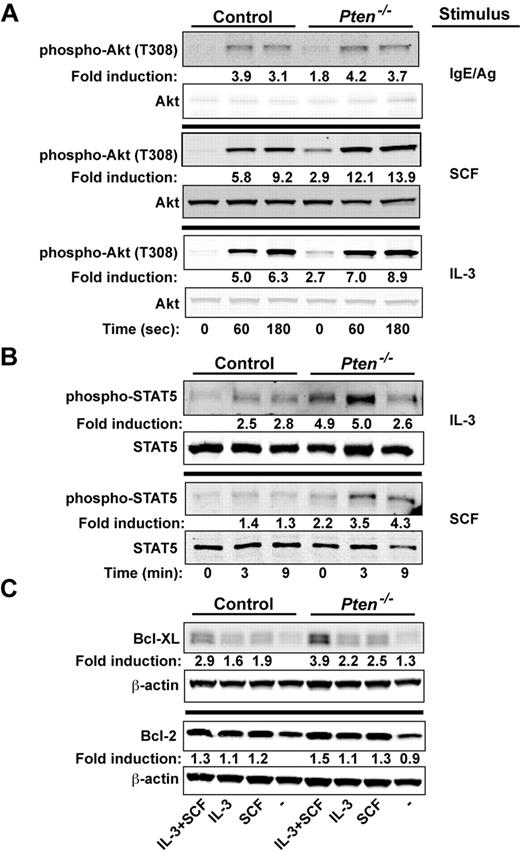

PTEN deficiency enhances proliferative and survival signals in MCs

We explored whether signals important to proliferation and survival of MCs might be altered by the absence of PTEN. We previously demonstrated16 that the silencing of PTEN expression in human MCs caused increased phosphorylation of Akt (T308, a site whose phosphorylation is dependent on PI3K activity), a key regulator of cell proliferation and survival.28 Because the PI3K pathway has been shown to be central to Kit-, IL-3–, and FcϵRI-mediated MC proliferation and survival,29-31 we examined how these stimuli might affect the activation of Akt. As shown in Figure 4A, phosphorylation of Akt at T308 was enhanced in BMMCs (∼ 2-fold) in the absence of any stimuli. A trend (albeit not significant) toward enhanced phosphorylation of T308 was observed on FcϵRI stimulation. A significant enhancement was observed when PTEN-deficient MCs were stimulated with IL-3. However, the most marked enhancement in Akt (T308) phosphorylation was evident on stimulation of Kit with SCF. These findings demonstrated the key regulatory role of PTEN in dampening Akt phosphorylation, particularly on Kit engagement.

PTEN deficiency enhances the proliferative and survival signals of MCs. (A) Cells (5 × 105 cells) were stimulated with IgE/Ag, SCF, or IL-3 and lysed in RIPA buffer. Phosphorylated Akt was probed with anti–phosho-Akt (T308). Total Akt was used as the loading control. (B) IL-3 or SCF-mediated phosphorylation of STAT5 was determined by immunoblot. Stimulated cells (5 × 105 cells) were lysed in RIPA buffer, and phosphorylated STAT5 was detected with an antibody recognizing phosphorylated STAT5. One representative of 4 experiments is shown. (C) BMMCs (5 × 105 cells) incubated in the absence of cytokines for 3 hours and restimulated with SCF, IL-3, or SCF and IL-3 for 24 hours. Expression of antiapoptotic factors (Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL) was measured after 24 hours by immunoblotting with antibodies to Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL. β-actin was used as loading control. (A-C) One representative of a minimum of 4 experiments is shown. Fold induction reflects the mean of all experiments normalized to WT control (0 time; A-B) or to WT control with no treatment (C).

PTEN deficiency enhances the proliferative and survival signals of MCs. (A) Cells (5 × 105 cells) were stimulated with IgE/Ag, SCF, or IL-3 and lysed in RIPA buffer. Phosphorylated Akt was probed with anti–phosho-Akt (T308). Total Akt was used as the loading control. (B) IL-3 or SCF-mediated phosphorylation of STAT5 was determined by immunoblot. Stimulated cells (5 × 105 cells) were lysed in RIPA buffer, and phosphorylated STAT5 was detected with an antibody recognizing phosphorylated STAT5. One representative of 4 experiments is shown. (C) BMMCs (5 × 105 cells) incubated in the absence of cytokines for 3 hours and restimulated with SCF, IL-3, or SCF and IL-3 for 24 hours. Expression of antiapoptotic factors (Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL) was measured after 24 hours by immunoblotting with antibodies to Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL. β-actin was used as loading control. (A-C) One representative of a minimum of 4 experiments is shown. Fold induction reflects the mean of all experiments normalized to WT control (0 time; A-B) or to WT control with no treatment (C).

We next assessed the phosphorylation of STAT5, a transcription factor shown to be essential for MC development and survival.32-34 Interestingly, phosphorylated STAT5 is seen in MCs from systemic mastocytosis patients, particularly those with the Kit D816V mutation,35,36 and has been connected to the PI3K pathway and the induction of the Bcl-2 family of survival genes.37 As shown in Figure 4B, STAT5 was strongly phosphorylated in PTEN-deficient MCs, with a 2- to 5- fold increase relative to the nonstimulated control MCs. Both IL-3 and SCF caused an additional enhancement of STAT5 phosphorylation, and this phosphorylation was more sustained with the latter stimulus. IL-3–stimulated MCs from Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/wt also had elevated levels of STAT5 phosphorylation relative to those from control Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/wt mice (supplemental Figure 8B)

We explored whether the survival-inducing Bcl-2 family members might be enhanced in the absence of PTEN. Whereas minor differences in Bcl-XL or Bcl-2 expression were observed before cell stimulation, both IL-3 and SCF increased Bcl-XL protein expression, and this was markedly enhanced when cells were stimulated with both (Figure 4C). In addition, the mRNA levels for the potent prosurvival genes Dad1 and Mcl-1 were also elevated (data not shown). Although a trend was observed in multiple experiments for increased expression of Bcl-2 protein, this was not significant; and in some experiments, no differences could be found. No significant changes in expression of key proapoptotic genes (eg, Bak, Bax, and caspase 3) was observed (data not shown). However, IL-3 deprivation revealed that PTEN-deficient MCs were more resistant to apoptosis (as measured by annexin V binding) relative to WT cells (supplemental Figure 9A). Collectively, the findings demonstrate that PTEN deficiency promotes MC proliferation and survival through the dysregulation of PI3K-dependent signals that enhance expression and activation of key proliferation and survival-promoting factors.

These findings suggested that the level of PTEN expression might control the proliferation and survival of MCs. To test this possibility, the human mastocytoma-derived HMC-1.2 cells, which carry the mutation of Kit at D816V and V560G, were transfected with a vector containing the Pten gene and expressing GFP as a reporter. Cells transfected with Pten showed a blunted proliferation relative to cells transfected with vector alone (supplemental Figure 9B).

PTEN deficiency in MCs enhances the effector responses induced by individual or synergistic stimulation via FcϵRI and Kit

Our previous work on human MCs16 demonstrated that PTEN deficiency caused a dysregulation of effector responses. We first addressed whether PTEN deficiency caused changes in the chemotaxis or adhesion of MCs. As shown in supplemental Figure 10A, the absence of PTEN in BMMCs did not alter their ability to migrate in response to SCF. Some enhancement in adhesion to fibronectin was observed (supplemental Figure 10B), but these differences were relatively small. No differences in the chemotactic response or in cell adhesion were observed when the cells were stimulated via FcϵRI (data not shown). However, constitutive IL-3 secretion was observed in PTEN-deficient MCs, and this secretion was enhanced in the presence of IgE and SCF (supplemental Figure 10C).

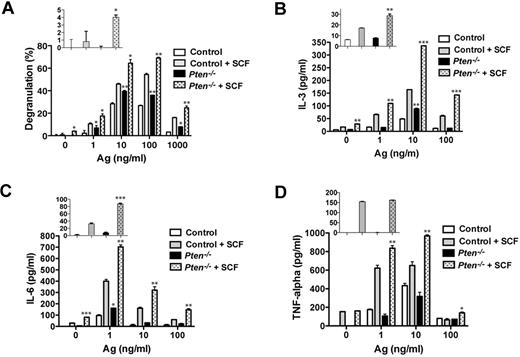

Consistent with our previous results in human MCs,16 PTEN deficiency failed to promote substantial degranulation in nonstimulated MCs (Figure 5A inset). Ag engagement led to an increased degranulation response relative to control cells, and this was further enhanced by the addition of SCF as a costimulus. At an optimal dose of Ag, PTEN-deficient MCs showed a 30% to 50% enhancement in degranulation relative to control cells (Figure 5A). As shown in Figure 5B-D, PTEN deficiency enhanced FcϵRI-dependent secretion of IL-3 and IL-6, but not of TNF. In the absence of any stimulation, IL-3 and IL-6 secretion was slightly elevated (albeit not significant for IL-3) in PTEN-deficient MCs relative to control cells. At suboptimal and optimal doses of Ag, SCF costimulation caused enhancement of all 3 cytokines. Thus, these findings demonstrate that the absence of Pten can cause selective enhancement MC effector responses in the absence or presence of a stimulus. Moreover, in the absence of Pten, SCF alone or in combination with other stimuli markedly elevated some MC effector responses.

PTEN deficiency enhances MC degranulation and cytokine production via FcϵRI or in combination with Kit. (A) FcϵRI-mediated MC degranulation as measured by β-hexosaminidase release. SCF (10 ng/mL) was used in combination with IgE/Ag. The percentage of β-hexosaminidase released after stimulation is expressed as a percentage of total cellular β-hexosaminidase. (Inset) β-hexosaminidase release with SCF stimulation in the absence of IgE/Ag. One representative of 3 experiments is shown. (B-D) IL-3, IL-6, and TNF production was measured by ELISA. (Inset) Cytokine release with SCF stimulation in the absence of IgE/Ag. Statistical analysis by an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test compared with control cells stimulated with SCF: *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. One representative of 4 experiments is shown.

PTEN deficiency enhances MC degranulation and cytokine production via FcϵRI or in combination with Kit. (A) FcϵRI-mediated MC degranulation as measured by β-hexosaminidase release. SCF (10 ng/mL) was used in combination with IgE/Ag. The percentage of β-hexosaminidase released after stimulation is expressed as a percentage of total cellular β-hexosaminidase. (Inset) β-hexosaminidase release with SCF stimulation in the absence of IgE/Ag. One representative of 3 experiments is shown. (B-D) IL-3, IL-6, and TNF production was measured by ELISA. (Inset) Cytokine release with SCF stimulation in the absence of IgE/Ag. Statistical analysis by an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test compared with control cells stimulated with SCF: *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. One representative of 4 experiments is shown.

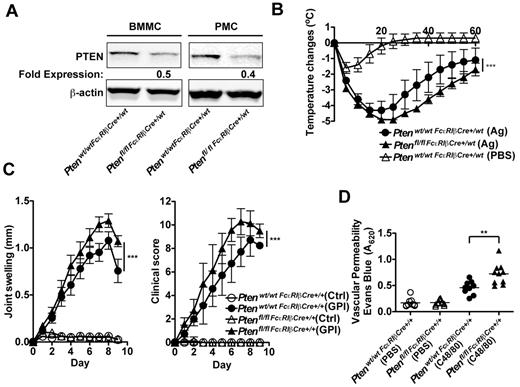

MC-specific PTEN deletion in vivo causes enhanced allergic responses and increased vascular permeability

Given that MC responses are enhanced in the absence of PTEN, that some patients with mastocytosis show increased allergic responses and other effects of MC degranulation,4,6,17 and that recent studies have identified the presence of D816V MC clonal expansion in anaphylactic patients who do not show the classic features of systemic mastocytosis,38 we explored whether mice deficient in PTEN had elevated allergic and other inflammatory responses on a challenge. To test allergic responses, in vivo experiments were conducted using aged Ptenfl/fl-FcϵRIβCre+/wt mice that expressed Cre recombinase from a single FcϵRIβ allele. Although young mice did not show efficient deletion of the targeted Pten locus (Figure 3B), in the course of these studies we found that as mice aged they showed a more significant loss of PTEN expression in their MCs (Figure 6A) and had markedly increased numbers of MCs in peripheral tissues, similar to mice expressing Cre recombinase from both FcϵRIβ alleles. This is probably because of the preferential enhancement of proliferation and survival for PTEN-deficient MCs, which would more clearly manifest with age. Because of their FcϵRIβ allele heterozygosity, MCs from these mice expressed FcϵRI and could be challenged in this manner. Analysis of peritoneal MCs from the aged (> 25 weeks) Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/wt mice (hetereozygotes at the FcϵRIβ locus) showed a 50% to 60% reduction in PTEN expression (Figure 6A), and these MCs expressed normal numbers of FcϵRI (data not shown). Measurement of body temperature loss after an FcϵRI-dependent systemic anaphylactic challenge showed a more sustained loss and slower recovery of body temperature in mice carrying a deficiency of Pten in the MC compartment (Figure 6B). Thus, the in vivo anaphylactic response of Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/wt mice was consistent with increased numbers and enhanced sensitivity of MCs.

Deletion of Pten in MCs causes increased anaphylactic responses and enhanced vascular permeability in vivo. (A) BMMCs and peritoneal MCs (PMCs; 5 × 105 cells) were lysed in RIPA buffer. PTEN expression was determined by immunoblot with an antibody to PTEN. β-actin was used as loading control. One representative of 4 experiments is shown. (B) Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/wt mice and Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/wt mice (age, 24 weeks) were passively sensitized with DNP-specific IgE and challenged 24 hours later with Ag (DNP-HSA) or pseudo-challenged with an equal volume of PBS. Anaphylactic reaction was measured by temperature change. Data are mean ± SEM of a minimum of 5 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was by 2-way ANOVA: ***P < .0001. Significant differences were observed between 25 and 45 minutes after challenge. (C) Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice and Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice (age, 16 weeks) were inoculated intraperitoneally with K/BxN serum containing autoantibodies to glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) or with control serum (Ctrl). Joint swelling and clinical score were determined as described in “Anaphyloxis and arthritis models.” Data are mean ± SEM of a minimum of 8 mice. Statistical analysis was by a 2-way ANOVA: ***P < .0001. Significant differences were observed between 6 and 9 days after challenge. (D) Evans blue dye (200 μL) was injected intravenously in Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice and Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice. Subsequently, they were challenged intradermally with 20 μL compound 48/80 (C48/80, 1.75 mg/mL) in PBS or as control with an equal volume of PBS. Vascular permeability was measured by extravasation of the dye into the ear tissue. Data are mean ± SEM from 10 mice. Statistical analysis was by unpaired 2-tailed Student t test: **P < .001.

Deletion of Pten in MCs causes increased anaphylactic responses and enhanced vascular permeability in vivo. (A) BMMCs and peritoneal MCs (PMCs; 5 × 105 cells) were lysed in RIPA buffer. PTEN expression was determined by immunoblot with an antibody to PTEN. β-actin was used as loading control. One representative of 4 experiments is shown. (B) Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/wt mice and Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/wt mice (age, 24 weeks) were passively sensitized with DNP-specific IgE and challenged 24 hours later with Ag (DNP-HSA) or pseudo-challenged with an equal volume of PBS. Anaphylactic reaction was measured by temperature change. Data are mean ± SEM of a minimum of 5 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was by 2-way ANOVA: ***P < .0001. Significant differences were observed between 25 and 45 minutes after challenge. (C) Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice and Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice (age, 16 weeks) were inoculated intraperitoneally with K/BxN serum containing autoantibodies to glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) or with control serum (Ctrl). Joint swelling and clinical score were determined as described in “Anaphyloxis and arthritis models.” Data are mean ± SEM of a minimum of 8 mice. Statistical analysis was by a 2-way ANOVA: ***P < .0001. Significant differences were observed between 6 and 9 days after challenge. (D) Evans blue dye (200 μL) was injected intravenously in Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice and Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice. Subsequently, they were challenged intradermally with 20 μL compound 48/80 (C48/80, 1.75 mg/mL) in PBS or as control with an equal volume of PBS. Vascular permeability was measured by extravasation of the dye into the ear tissue. Data are mean ± SEM from 10 mice. Statistical analysis was by unpaired 2-tailed Student t test: **P < .001.

To determine whether PTEN deficiency enhanced other inflammatory responses, we used the KRN model of arthritis21,39 in the MC-specific PTEN-deficient mice with homozygosity of Cre expression from the FcϵRIβ locus (Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice). These mice were preferred because MC numbers in peripheral tissues were higher than that seen in Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/wt mice and induction of MC-dependent arthritis in this model does not require FcϵRI expression. As shown in Figure 6C, joint swelling was significantly elevated in Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice relative to control mice. Moreover, clinical scoring of disease severity showed a significant enhancement in Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice. Notably, however, histologic analysis of tissue damage revealed no significant difference in inflammation, bone, or cartilage erosion between control and Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice (data not shown). Because the control Ptenwt/wtFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice develop a robust inflammatory response with bone and cartilage erosion, discerning minor differences was not possible. Joint and tissue swelling is the major determinant of the clinical score for arthritis in this model; thus, the findings argued for a possible increase in vascular permeability rather than a significantly enhanced tissue erosion. To assess this possibility, a local skin challenge (passive cutaneous anaphylaxis) was performed on Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/+ mice using compound 48/80 (a potent MC secretagogue). As shown in Figure 6D, measurement of vascular permeability by the extravasation of Evans blue dye in the skin demonstrated an enhanced response in Ptenfl/flFcϵRIβCre+/+ relative to control mice. The collective findings demonstrate that loss of expression of PTEN in the MC compartment causes enhanced allergic sensitivity, a feature previously associated with MC proliferative diseases.4,6,17,40

Discussion

MC proliferative diseases are heterogeneous and are characterized by the accumulation of MCs in one or more organs. These diseases may be cutaneous, extracutaneous, or systemic. They may be associated with a clonal hematologic non-MC lineage disease and may be aggressive and show features of leukemia or sarcoma.4,6,17 The mutation of Kit (D816V) is in common to a majority of patients with mastocytosis and results in the constitutive activation of this receptor tyrosine kinase (which functions as a cell surface receptor for SCF). Normally, binding of SCF to Kit causes the activation of its kinase activity and the subsequent induction of signals that can regulate cell proliferation and survival.31,41,42 It is well recognized that Kit- (and IL-3)–mediated MC proliferation is highly dependent on the activation of PI3K, as inhibitors of this pathway abrogate this response.9 The p85α regulatory subunit of PI3K has been shown to associate with Kit, and mutation of the binding site on Kit (Y721F) for the p85 PI3K subunit, in the context of the D816V mutation of Kit, was shown to abrogate cell proliferation.7,10,14 This together with the reported requirement of the Src homology 2-containing inositol 5′ phosphatase (which is also be recruited to lipid raft domains) in controlling Kit-dependent MC degranulation43 suggests that tight regulation of PI3K signaling in lipid rafts is a requirement in MC homeostasis.

Similarly, there is evidence for a role of STAT5 in regulating Kit-dependent MC proliferation. In the mouse, STAT5 is required for MC development and survival,33,44 and STAT5 activation occurs on stimulation with IL-3, SCF, or FcϵRI.33,44 Several studies have demonstrated a relationship between STAT5 activation, PI3K activity, and the Kit D816V mutation in control of myeloproliferative disease and neoplastic MC growth.8,35,36 Studies have demonstrated a key regulatory role of the N-domain of STAT5a in myeloproliferative disease. Retroviral reconstitution of STAT5ab-null MCs with WT or N-domain deleted STAT5a demonstrated the requirement of this domain in inducing the survival gene Bcl-2 and in suppressing the microRNA 15b/16 leading to maintained Bcl-2 protein expression.45

What is still unclear is whether PI3K signals are upstream of STAT5 activation, or vice versa. A recent study8 using a constitutively active form of STAT5 (cS5F) showed that its overexpression results in activation of PI3K signals and Akt phosphorylation as well as MC proliferation. Thus, it appears that expression of an active STAT5 or deletion of Pten results in the induction of complementary signals that cause dysregulated MC proliferation. This view is supported by the observation that pharmacologic inhibition of PI3K or expression of a dominant negative STAT5 as well as deletion of the STAT5 gene caused a similar loss of Kit-dependent MC proliferative ability.8,9,14,33 Moreover, it has been shown that these 2 pathways can crosstalk through the association of PI3K and STAT5 with the Gab2 adapter protein, and this association is required for cell proliferation.46 Thus, induction of one pathway might in turn cause the assembly of a signaling complex and the activation of crosstalk required for MC proliferation. Consistent with this view, our experiments with PTEN-deficient MCs showed induction of Akt and STAT5 phosphorylation, as well as Bcl-XL expression, which was particularly prominent when Kit was engaged or activated as a costimulator. These aforementioned features are consistent with the molecular and pathophysiologic characteristics seen in mastocytosis.35,36 The collective findings demonstrate that the loss of normal PI3K pathway regulation is central to dysregulated MC proliferation and suggest the possibility that PTEN mutations could be a factor in mastocytosis. Interestingly, analysis of 2 MC lines that carry Kit mutations showed decreased expression of PTEN relative to a growth factor-dependent MCs (supplemental Figure 11). On the other hand, a limited analysis of skin biopsies from 4 mastocytosis patients showed no obvious difference in the levels of MC PTEN expression relative to MCs in normal skin. However, it is possible that, although PTEN expression may be normal, its activity is impaired. Such investigation may be warranted and requires a careful analysis of mastocytosis resulting from Kit mutations or other causes.

PTEN has long been described as a tumor suppressor, and mutations of PTEN are common in brain, breast, and prostate cancers.47 In mice, lymphomas are found at higher incidence than other malignancies in both male and female mice.48 However, besides lymphomas, PTEN deficiency in male mice caused the development of prostate and intestinal cancer as well as squamous cell carcinoma, whereas in female mice, squamous cell carcinoma and endometrial cancer were more prominently observed.48 This suggests that dysregulation of PI3K signals is insufficient to engender oncogenesis in all tissues and/or that other signals may be required. Interestingly, in vitro experiments did not reveal increased colony formation potential for PTEN-deficient MCs (data not shown), nor did we find mastocytomas in mice completely deficient of PTEN or those where Pten was deleted selectively from MCs. Nonetheless, PTEN-deficient MCs were found to be somewhat clustered in vivo, suggesting the presence of a microenvironment conducive to MC proliferation and/or MC recruitment and function. A similar enhanced proliferative environment has been described in the bone marrow of patients with systemic mastocytosis, where MCs are found to aggregate around lymphoid cells in a microenvironment that contains high levels of SCF.5,49

A diagnostic feature of systemic mastocytosis is the increased numbers of MCs in the bone marrow, a characteristic we did not observe in PTEN-deficient mice. However, it should be noted that some cases of cutaneous mastocytosis have been reported that seemingly do not involve the bone marrow.49 Regardless, our findings show that PTEN deficiency in MCs causes dysregulated proliferation with many of the features of systemic mastocytosis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Section, the Flow Cytometry Section, and the Light Imaging Section of the Office of Science and Technology, National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases for their support.

This work was supported by the intramural program of National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: Y.F. and J.R. conceived and directed the project, designed experiments, summarized data, and wrote the manuscript; Y.F., N.C., A.O., J.L.S., K.T., E.S., S.D., and S.O. performed experiments and analyzed data; Y.F., W.H.L., and S.B. generated mice for this study; K.G., M.C., T.M.W., M.K., and D.M.L. provided key reagents and/or expertise in used models; and M.C. and D.M.L. contributed histologic and data analysis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.M.L. is currently employed by Novartis Pharmaceuticals AG. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Juan Rivera, National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bldg 10, Rm 9C103, Bethesda, MD 20892-1930; e-mail: juan_rivera@nih.gov.