Abstract

Before, during, and after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), patients experience considerable physical and psychologic distress. Besides graft-versus-host disease and infections, reduced physical performance and high levels of fatigue affect patients' quality of life. This multicenter randomized controlled trial examined the effects of a partly self-administered exercise intervention before, during, and after allo-HSCT on these side effects. After randomization to an exercise and a social contact control group 105 patients trained in a home-based setting before hospital admission, during inpatient treatment and a 6- to 8-week period after discharge. Fatigue, physical performance, quality of life, and physical/psychologic distress were measured by standardized instruments at baseline, admission to, and discharge from hospital and 6 to 8 weeks after discharge. The exercise group showed significantly improvement in fatigue scores (up to 15% improvement in exercise group vs up to 28% deterioration in control; P < .01-.03), physical fitness/functioning (P = .02-.03) and global distress (P = .03). All effects were at least detectable at one assessment time point after hospitalization or repeatedly. Physical fitness correlated significantly with all reported symptoms/variables. In conclusion, this partly supervised exercise intervention is beneficial for patients undergoing allo-HSCT. Because of low personnel requirements, it might be valuable to integrate such a program into standard medical care.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is a treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematopoietic diseases and associated with numerous treatment-related somatic, psychologic, and psychosocial side effects and disease-specific 5-year survival rates from 5% to 80%.1,2 Besides graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and infections, reduced physical performance and functioning, and particularly high levels of fatigue, negatively affect patients' quality of life (QoL).3,4 Furthermore, affective disorders (depression, anxiety disorders) and somatic complications, such as diarrhea, nausea, and pain, cause distress to occur and reinforce each other.5-8 This treatment-related burden can be severely debilitating and may limit reintegration into usual life activities.9 In the past 10 years, intensive research has substantially improved medical treatment options (eg, toxicity-reduced therapy regimens, donor lymphocyte infusions) and supportive care (eg, antifungal and GVHD treatment). Based on these developments, long-term survival rates increased continuously, and allo-HSCT is available even for older patients or those with more comorbidities.1

In light of the increasing numbers of successfully treated patients, the need is growing for evidence-based adjuvant therapy options, which reduce treatment-related side effects and consequently enhance the rehabilitation process. A recent review of our group summarized findings from 15 studies published within the last 20 years, proposing that physical exercise constitutes a potentially promising intervention to moderate such side effects and has a beneficial influence on patients' QoL during and after HSCT.10 Specifically, among allo-HSCT patients, exercise seems to result in positive interventional effects not only on endurance capacity,11-14 muscle strength,11,14,15 and Karnofsky performance score,12 but also on perceived physical, emotional, and social states,16,17 fatigue,12,17 and QoL.11,17 Furthermore, improvements in immunologic parameters18 and different side-effect symptom clusters19 have been reported.

However, despite these promising initial results, methodical problems of these studies hamper the interpretation. Joint inclusion of allogeneic and autologous patients,11,13,17 the lack of control groups,12,17 and small sample sizes limit their value. All but one study20 performed supervised interventions during or after allo-HSCT13,15,16 in favor of a high internal validity, even though supervised exercise training may not reflect daily clinical conditions. Furthermore, no study included the pre-HSCT treatment phase. However, an inclusion of that phase might be especially important because many patients also have pre-HSCT treatment and experience considerable physiologic and psychologic impairments before allo-HSCT.8,21,22 Thus, there is no clear evidence regarding the most beneficial type or timing of physical exercise as an adjuvant intervention in patients undergoing allo-HSCT.

To identify benefits of exercise performed during the entire HSCT time period, we conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) starting during medical checkup before allo-HSCT, continuing throughout the inpatient phase, and ending 6 to 8 weeks after discharge. The intervention was designed to be practiced without intensive therapeutic support in home-based conditions because the catchment areas of both centers were up to 100 km. The primary endpoint was fatigue. Secondary outcomes explored endurance performance via 6-minute walk test (6MWT), isometric muscle strength, functional performance status, physical activity levels via pedometer step count, health-related QoL, psychologic well-being, and distress.

Methods

The study was a prospective, multicenter, clinical RCT comparing a self-administered exercise intervention with a social contact control group (n = 105). It was conducted at the University Clinic Heidelberg (Heidelberg, Germany) and the German Clinic for Diagnostic (Wiesbaden, Germany). The protocol was approved by the Ethic Committee II of the University of Heidelberg/Mannheim (no. 2007-089N-MA) and the Landesaerztekammer Hessen (no. E-154/2007 MC). Eligible participants were identified by hemato-oncologists in the related transplantation center. Enrollment took place during medical visits in preparation for allo-HSCT. After informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, patients were randomized by the minimization procedure23 stratified by age, disease, and sex for each center to an exercise or a pedometer-wearing control group with the same frequency of social contact by study personnel.

Exercise intervention

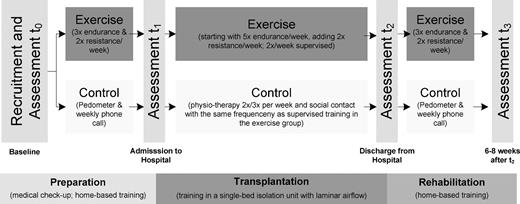

Participants in the exercise group started exercising on an outpatient basis before allo-HSCT (as a general rule, 1-4 weeks before admission to the hospital; Table 2), continued during the inpatient period and perpetuated until 6 to 8 weeks after discharge from the hospital. The outpatient intervention was conducted self-directed at home, whereas the inpatient period was partly supervised for 2 times per week and adapted to the conditions of an isolation unit (Figure 1). After randomization, patients received a practical introduction by an exercise specialist and furthermore a training manual (including exercise DVD). Intervention guidelines consisted of 3 endurance (up to 5 during hospitalization) and 2 resistance training sessions per week. Warm-up and cool-down periods were a few minutes of light aerobic activity (eg, walk/rise on tiptoe) and stretching. Endurance training in the outpatient setting was recommended primarily as (brisk) walking for 20 to 40 minutes; bicycling and treadmill walking during hospitalization. If patients had experience in Nordic walking (walking with specially designed poles imitating the motion of cross-country skiing) or jogging, these techniques were also recommended. Strength training included exercises for the upper and lower extremities with and without a set of color-coded stretch bands with different levels of resistance (8-20 repetitions, 2 or 3 sets). Three different strength-training protocols were used: (1) focused on extremities, (2) the entire body, or (3) bed exercises (limited to inpatient period). In weekly phone calls, study staff reviewed adherence to the intervention and identified problems. Patients also received a phone number to contact the exercise therapist in case of questions.

Training intensity was adapted using the Borg scale24 (target scores 12-14 for endurance and 14-16 for resistance exercises). Furthermore, patients were required to complete a daily log, including an assessment of pain, fatigue, emotional status, and distress. This assessment was used to self-rate patients' well-being and group them into 3 different categories (red, yellow, and green) for tailoring the exercise intervention. Green coded for subjective good or normal health status and included the most challenging exercise recommendations. Yellow and red corresponded to medium or bad health status resulting in less challenging recommendations. An example referring to endurance training in the outpatient period: Participants rating themselves green were suggested brisk walking approximately 30 to 40 minutes. Yellow rating suggested 20 to 30 minutes and red 15 to 20 minutes. Independent of the recommendations, patients were required to walk without interruption if physically able. Contraindications for starting a training session were infections (body temperature > 38°C), severe pain, nausea and dizziness, platelet counts < 10 000/μL (for 10 000-20 000 μL approval by the treating physician was sought), and hemoglobin < 8 g/dL. The exercise sessions were stopped if pain, dizziness, or other contraindications occurred.

Control group

Participants assigned to the control group were told that moderate physical activity is favorable during the treatment process without further advice. To record their daily physical activity in the outpatient setting, patients received step counters with the request to wear and record them daily. During hospitalization, physiotherapy was offered up to 3 sessions per week (average duration/session, 30 minutes.). To avoid sociopsychologic bias, the controls were visited by study personnel with the same frequency. Throughout these visits, patients were asked about their current health status and feelings. For the period of hospitalization, the control group had the same access to stationary cycles and treadmills as the intervention group. They also completed all outcome measures within the same time frame.

Data collection and endpoints

Demographic data, physical activity profiles, and anthropometric characteristics were collected at baseline. Medical and transplantation variables were obtained from patients' medical records. The primary outcome fatigue was measured by the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) of Smets et al,25 which is composed of 20 items yielding to 5 different subscales (general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced activity, reduced motivation, and mental fatigue) representing the multidimensionality of the fatigue syndrome. Furthermore, the fatigue subscales of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) were also used for primary outcome assessment. Secondary outcomes, such as physical capacity, QoL, anxiety, depression, and distress, were ascertained as mentioned in the last paragraph of this section. To document exercise adherence, adverse events, and symptoms, the patients kept a daily log.

Endurance performance was assessed using the 6MWT protocol by the American Thoracic Society.26 The test has been used extensively in clinical exercise trials to estimate aerobic capacity and was conducted as described on a 70-m hallway, except that the tester followed the subjects for safety reasons. Before, during, and after testing, pulse frequency and perceived exertion (Borg Scale) were monitored. O2 saturation was not measured. Maximal isometric voluntary strength was assessed with a hand-held dynamometer (C.I.T. Technics). Elbow flexors and extensors, shoulder abductors, hip abductors, and flexors as well as knee flexors and extensors were tested bilaterally. Test positions were standardized according to Bohannon27 and the manufacturer's manual. The patients were required to complete each test situation with maximum of voluntary strength starting with low force and rising quickly to the maximum. Each measurement was repeated 3 times and averaged. Values were excluded if they differed more than 10% from median. Here we present summed up scores for upper and lower extremity strength. All physical capacity assessments were performed by one examiner per center. Patients were instructed on proper technique and advised to stop if they experienced pain or other complications during the test.

Patients' QoL was assessed by the EORTC QLQ-C30 to evaluate different factors of health-related QoL in 5 functional and 9 symptom subscales/items.28 The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale assesses psychologic well-being29,30 ; it was specifically developed for patients with physical illnesses and has been extensively used in the setting of cancer treatment, including HSCT patients.31 The POMS (35 items) was used to assess 4 separate subscale scores for depression, anger/hostility, vigor, and fatigue32 and has been widely used in the assessment of mood changes resulting from a variety of interventions, including exercise trials, and also in HSCT.33 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress-Thermometer34 used consists of a visual analog scale from 0 to 10 and a 34-item dichotomy problem list. A score of 5 is internationally recommended as an indicator that a patient is distressed and needs support.

All assessments were conducted at 4 time points: baseline (medical checkup before allo-HSCT), admission to hospital, discharge from hospital, and 6 to 8 weeks after discharge (Figure 1).

Statistical analyses

Baseline comparisons were performed using Student t test (metric data), Wilcoxon test (ordinal data), and Fisher exact test (categorical data) as appropriate. Trial outcomes were evaluated in an intent-to-treat analysis. For patient-rated outcomes and physical performance data, Student t test was used for independent group comparisons at measurement points and to calculate effect difference between 2 fixed time points (eg, group-specific changes between baseline and at the end of the study). One-factorial analysis of variance for repeated measurements was used to compare the group-specific development over study time. Normality distribution of the data was tested with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Homogeneity of variances was evaluated using the Levene statistic. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to mark associations between physical performance and fatigue variables. The results of comparative and correlation tests were considered as significant with a value of P < .05. Bonferroni correction was carried out for the 5 analyses of variance pertaining to the primary outcome. Accordingly, P values < .01 were considered significant when testing whether change of fatigue would differ across groups. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (German Version 15.0 for Windows).

Results

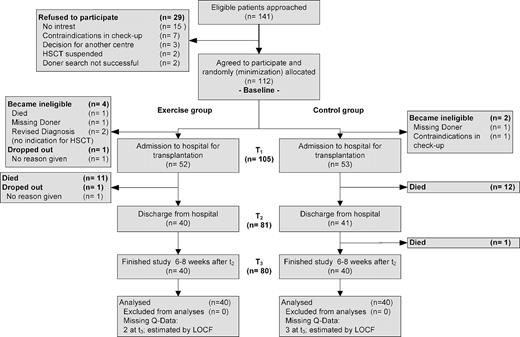

Patient recruitment took place from May 2007 (German Clinic for Diagnostics) or October 2007 (University Clinic of Heidelberg) until September 2008 (Figure 2). The last patient completed the study in February 2009. Of 141 patients asked to participate, 112 (79.4%) agreed. Major reasons for not participating were lack of interest in the study (n = 15) or contraindications during medical checkup (n = 7). One patient dropped out before allo-HSCT, and 6 patients became ineligible because no HSCT was performed, resulting in a final sample size of 105 (93.8%). During the entire study period, 24 patients (11 in the exercise and 13 in the control group) died and one patient of the exercise group decided to drop out without giving any reasons. Thus, the final analysis included 80 patients (40 per group).

Patients' demographic and medical characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between groups at baseline, including the conditioning regimens' intensity and GVHD incidence over the course of study time. The majority were sedentary at baseline, with 79 of 105 patients (75.2%) reporting physical activity less than one time per week. Participants of the exercise group stayed a median of 115 days in the study, controls 110 days (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences regarding enrollment before HSCT or timing of the following study periods between groups.

Baseline demographic and medical characteristics

| . | All (n = 105) . | Exercise (n = 52) . | Control (n = 53) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center | ||||

| Heidelberg | 25 | 13 | 12 | |

| Wiesbaden | 80 | 39 | 41 | |

| Mean age, y (range) | 48.8 (18-71) | 47.6 (18-70) | 50 (20-71) | .38 |

| Sex, no. (%) | .10* | |||

| Male | 71 | 32 (45) | 39 (55) | |

| Female | 34 | 21 (62) | 13 (38) | |

| Sedentary (< 1×/week physically active) at baseline, no. (%) | 79 | 38 (48) | 41 (52) | .66* |

| Karnofsky score t0 (median) | 90 | 90 | 90 | .40† |

| 90-100 | 82 | 43 | 39 | |

| 80-90 | 20 | 7 | 13 | |

| < 80 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 24.9 (4.1) | 25.1 (4.3) | 24.7 (3.9) | .66 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| AML | 22 | 12 | 10 | |

| ALL | 14 | 6 | 8 | |

| CML | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| CLL | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| MDS | 12 | 7 | 5 | |

| Secondary AML | 11 | 6 | 5 | |

| MPS | 13 | 7 | 6 | |

| Multiple myeloma | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Other lymphomas | 20 | 7 | 13 | |

| Aplastic anemia | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Source of stem cell | > .999* | |||

| Bone marrow | 15 | 7 | 8 | |

| Peripheral blood cells | 90 | 45 | 45 | |

| Donor-recipient characteristics | .49* | |||

| HLA-identical (related) | 28 | 13 | 15 | |

| HLA-matched/unrelated | 56 | 26 | 30 | |

| HLA-mismatched/unrelated | 21 | 13 | 8 | |

| Conditioning regimens | ||||

| FLAMSA | 28 | 14 | 14 | |

| TBI/etoposide | 12 | 5 | 7 | |

| Flu/Bu | 11 | 7 | 4 | |

| TBI/Flu/Cyclo | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| BCNU/Flu/Mel | 7 | 1 | 6 | |

| Flu/Bu/Cyclo | 7 | 2 | 5 | |

| TBI/Cyclo | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| Bu/Cyclo | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| TBI/Flu | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| Treo/Flu | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Flu/Mel | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Flu/Cyclo | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| TBI/Thi/Flu | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Cyclo | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mel | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Intensity of conditioning regimens | .82* | |||

| Myeloablative | 24 | 11 | 13 | |

| Reduced intensity | 81 | 41 | 40 | |

| TBI | 36 | 18 | 18 | > .999* |

| GVHD incidence | 39 (37) | 21 (40) | 18 (34) | .55* |

| Skin, no. (%) | 35 (32) | 18 (35) | 17 (32) | |

| Gastrointestinal, no. (%) | 10 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | |

| Liver, no. (%) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| . | All (n = 105) . | Exercise (n = 52) . | Control (n = 53) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center | ||||

| Heidelberg | 25 | 13 | 12 | |

| Wiesbaden | 80 | 39 | 41 | |

| Mean age, y (range) | 48.8 (18-71) | 47.6 (18-70) | 50 (20-71) | .38 |

| Sex, no. (%) | .10* | |||

| Male | 71 | 32 (45) | 39 (55) | |

| Female | 34 | 21 (62) | 13 (38) | |

| Sedentary (< 1×/week physically active) at baseline, no. (%) | 79 | 38 (48) | 41 (52) | .66* |

| Karnofsky score t0 (median) | 90 | 90 | 90 | .40† |

| 90-100 | 82 | 43 | 39 | |

| 80-90 | 20 | 7 | 13 | |

| < 80 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 24.9 (4.1) | 25.1 (4.3) | 24.7 (3.9) | .66 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| AML | 22 | 12 | 10 | |

| ALL | 14 | 6 | 8 | |

| CML | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| CLL | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| MDS | 12 | 7 | 5 | |

| Secondary AML | 11 | 6 | 5 | |

| MPS | 13 | 7 | 6 | |

| Multiple myeloma | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Other lymphomas | 20 | 7 | 13 | |

| Aplastic anemia | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Source of stem cell | > .999* | |||

| Bone marrow | 15 | 7 | 8 | |

| Peripheral blood cells | 90 | 45 | 45 | |

| Donor-recipient characteristics | .49* | |||

| HLA-identical (related) | 28 | 13 | 15 | |

| HLA-matched/unrelated | 56 | 26 | 30 | |

| HLA-mismatched/unrelated | 21 | 13 | 8 | |

| Conditioning regimens | ||||

| FLAMSA | 28 | 14 | 14 | |

| TBI/etoposide | 12 | 5 | 7 | |

| Flu/Bu | 11 | 7 | 4 | |

| TBI/Flu/Cyclo | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| BCNU/Flu/Mel | 7 | 1 | 6 | |

| Flu/Bu/Cyclo | 7 | 2 | 5 | |

| TBI/Cyclo | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| Bu/Cyclo | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| TBI/Flu | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| Treo/Flu | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Flu/Mel | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Flu/Cyclo | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| TBI/Thi/Flu | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Cyclo | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mel | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Intensity of conditioning regimens | .82* | |||

| Myeloablative | 24 | 11 | 13 | |

| Reduced intensity | 81 | 41 | 40 | |

| TBI | 36 | 18 | 18 | > .999* |

| GVHD incidence | 39 (37) | 21 (40) | 18 (34) | .55* |

| Skin, no. (%) | 35 (32) | 18 (35) | 17 (32) | |

| Gastrointestinal, no. (%) | 10 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | |

| Liver, no. (%) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 |

BMI indicates body mass index; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MPS, myeloproliferative syndrome; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; FLAMSA, fludarabine Ara-C amsacrin; TBI, total body irradiation; Flu, fludarabine; Bu, busulfan; Cyclo, cyclophosphamide; BCNU, 1,3-bis (2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea; Mel, melphalan; Treo, treosulfan; and Thi, thioglycollate.

Fisher exact test.

Wilcoxon test.

Days in treatment periods per group

| . | Outpatient before HSCT . | Duration of hospitalization . | Outpatient after HSCT . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 15 (5-90) | 43 (22-120) | 52 (40-83) |

| Exercise | 21 (5-112) | 45 (24-92) | 49 (39-63) |

| P | .12 | .64 | .08 |

| . | Outpatient before HSCT . | Duration of hospitalization . | Outpatient after HSCT . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 15 (5-90) | 43 (22-120) | 52 (40-83) |

| Exercise | 21 (5-112) | 45 (24-92) | 49 (39-63) |

| P | .12 | .64 | .08 |

Data are reported as median (range).

On average, 79% of exercise logs were returned. Based on these, average adherence to the exercise intervention was approximately 87% (Table 3). In the inpatient setting, participants had the lowest (83%) adherence rate, in particular because of medical contraindications, such as severe thrombopenia or fever.

Adherence to exercise intervention

| . | Study period . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before, % . | During, % . | After, % . | Mean, % . | |

| Adherence to protocol (exercise recommendation) | 87.5 | 83.0 | 91.3 | 87.3 |

| Missing documentation | 23.0 | 23.9 | 16.7 | 21.2 |

| . | Study period . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before, % . | During, % . | After, % . | Mean, % . | |

| Adherence to protocol (exercise recommendation) | 87.5 | 83.0 | 91.3 | 87.3 |

| Missing documentation | 23.0 | 23.9 | 16.7 | 21.2 |

Before indicates outpatient period from baseline (medical checkup) until admission; During, hospitalization; and After, outpatient period from discharge until study end (6-8 weeks later).

Patient-rated outcomes are shown in Table 4. For fatigue, the analysis showed significant group differences at the end of the intervention (t3) in the MFI scales “general fatigue” (gf) (P = .009) and “physical fatigue” (pf) (P = .01) and the POMS “fatigue” scale (pfs) (P = .004), but not the EORTC scale. In all subscales, the exercise group was superior compared with the controls. Furthermore, variance analyses for repeated measurements showed significant main effects for time and significant interaction effects (group by time) for all mentioned fatigue scales (P = .007 [gf]; P = .005 [pf]; P = .02 [pfs]), except the EORTC subscale. MFI “general fatigue” (P = .03) and POMS “fatigue” (P = .01) showed already significant group differences at discharge (t2). Pre-post effect analyses (baseline → discharge from hospital and baseline → end of intervention) were also statistically significant (Table 4). No intervention effect could be shown for the cognitive scales of the MFI.

Measured outcome variables

| . | t0 (medical checkup before HSCT) . | t1 (admission to hospital) . | t2 (discharge from hospital) . | t3 (6-8 weeks after discharge) . | Significant changes over time* . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFI | |||||||||

| General fatigue† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 12.0 | (4.0) | 11.2 | (4.2) | 12.7 | (3.6) | 11.0 | (4.1) | t0→ t2: .01*** |

| Control | 11.6 | (4.7) | 11.4 | (4.7) | 14.7 | (4.4) | 13.5 | (4.3) | t0→ t3: < .01*** |

| Student t test | .72 | .82 | .03 | ** | < .01 | *** | ANOVA: interaction (P ≤ .01***)‡ | ||

| Physical fatigue† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 12.4 | (4.2) | 11.5 | (4.1) | 12.9 | (4.1) | 11.4 | (4.7) | t0→ t2: .02** |

| Control | 11.5 | (5.0) | 11.2 | (4.8) | 14.6 | (4.7) | 14.0 | (4.5) | t0→ t3: < .01** |

| Student t test | .41 | .78 | .08 | .01 | ** | ANOVA: interaction (P ≤ .01***)‡ | |||

| Reduced activation† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 10.6 | (4.2) | 10.8 | (4.2) | 12.9 | (4.1) | 12.0 | (4.5) | |

| Control | 11.4 | (4.9) | 11.5 | (4.1) | 13.5 | (4.2) | 12.5 | (4.1) | |

| Student t test | .40 | .47 | .52 | .60 | |||||

| Reduced motivation† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 7.7 | (3.1) | 7.5 | (3.1) | 8.5 | (3.5) | 8.2 | (3.5) | |

| Control | 8.3 | (3.2) | 8.6 | (3.5) | 9.0 | (3.5) | 8.6 | (3.5) | |

| Student t test | .38 | .16 | .52 | .64 | |||||

| Mental fatigue† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 9.0 | (4.3) | 9.1 | (3.9) | 10.3 | (4.6) | 10.2 | (4.2) | |

| Control | 10.0 | (4.3) | 10.6 | (4.2) | 10.9 | (4.1) | 10.2 | (3.9) | |

| Student t test | .31 | .12 | .51 | .99 | |||||

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | |||||||||

| QoL | |||||||||

| Exercise | 60.8 | (18.8) | 64.2 | (20.3) | 53.8 | (19.9) | 61.7 | (22.2) | |

| Control | 55.6 | (21.6) | 62.7 | (23.2) | 47.3 | (18.1) | 57.1 | (17.3) | |

| Student t test | .25 | .77 | .13 | .30 | |||||

| Physical functioning | |||||||||

| Exercise | 74.5 | (15.4) | 75.2 | (18.5) | 63.3 | (22.5) | 73.7 | (19.6) | t1→ t3: .02** |

| Control | 71.0 | (24.5) | 76.0 | (23.8) | 53.5 | (25.1) | 63.5 | (22.2) | |

| Student t test | .45 | .86 | .07 | .03 | ** | ||||

| Role functioning | |||||||||

| Exercise | 52.5 | (28.1) | 53.8 | (31.9) | 31.7 | (29.4) | 45.0 | (28.5) | |

| Control | 53.8 | (35.7) | 56.3 | (36.9) | 33.3 | (34.8) | 43.8 | (32.8) | |

| Student t test | .86 | .75 | .82 | .87 | |||||

| Emotional functioning | |||||||||

| Exercise | 57.1 | (24.6) | 62.5 | (24.2) | 62.3 | (25.3) | 70.0 | (24.2) | |

| Control | 58.1 | (24.6) | 60.6 | (26.3) | 59.2 | (22.0) | 60.5 | (25.1) | |

| Student t test | .85 | .74 | .57 | .09 | |||||

| Cognitive functioning | |||||||||

| Exercise | 75.8 | (25.0) | 77.1 | (23.8) | 69.6 | (26.7) | 73.8 | (22.3) | |

| Control | 70.4 | (27.6) | 70.0 | (30.7) | 62.1 | (28.0) | 71.3 | (19.6) | |

| Student t test | .36 | .25 | .22 | .60 | |||||

| Social functioning | |||||||||

| Exercise | 50.0 | (30.7) | 49.6 | (32.1) | 43.8 | (31.3) | 49.2 | (32.5) | |

| Control | 49.6 | (33.2) | 53.8 | (31.5) | 42.1 | (29.2) | 46.7 | (29.3) | |

| Student t test | .95 | .56 | .81 | .72 | |||||

| Fatigue† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 45.0 | (24.4) | 39.2 | (26.3) | 60.3 | (28.5) | 49.7 | (28.9) | |

| Control | 46.1 | (32.2) | 41.4 | (31.2) | 66.4 | (27.4) | 60.8 | (29.2) | |

| Student t test | .86 | .73 | .33 | .09 | |||||

| Nausea and vomiting† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 9.6 | (16.8) | 7.1 | (13.6) | 24.2 | (31.8) | 13.8 | (22.3) | |

| Control | 10.4 | (19.1) | 8.8 | (19.2) | 27.1 | (28.2) | 19.2 | (26.6) | |

| Student t test | .84 | .66 | .67 | .33 | |||||

| Pain† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 23.8 | (28.2) | 29.6 | (29.6) | 32.1 | (32.8) | 25.0 | (31.8) | t1→ t3: < .01*** |

| Control | 25.8 | (33.3) | 20.0 | (27.8) | 35.4 | (29.3) | 35.8 | (28.9) | ANOVA: interaction (P = .04**) |

| Student t test | .76 | .14 | .63 | .12 | |||||

| Dyspnea† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 34.2 | (28.7) | 26.7 | (28.4) | 39.2 | (28.1) | 30.0 | (25.9) | |

| Control | 30.8 | (32.4) | 28.3 | (33.4) | 42.5 | (34.6) | 33.3 | (31.1) | |

| Student t test | .63 | .81 | .64 | .60 | |||||

| Insomnia† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 34.2 | (32.5) | 30.8 | (31.5) | 51.7 | (36.9) | 30.8 | (32.4) | |

| Control | 35.0 | (36.2) | 32.5 | (32.5) | 52.5 | (33.7) | 35.8 | (31.5) | |

| Student t test | .91 | .82 | .92 | .49 | |||||

| Appetite loss† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 22.5 | (28.6) | 15.0 | (27.2) | 48.3 | (38.5) | 31.7 | (35.4) | |

| Control | 24.2 | (31.1) | 21.7 | (33.4) | 60.0 | (30.4) | 42.5 | (37.7) | |

| Student t test | .80 | .33 | .14 | .19 | |||||

| Constipation† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 14.2 | (23.7) | 10.0 | (18.8) | 8.3 | (23.6) | 4.2 | (17.2) | |

| Control | 10.0 | (22.9) | 7.5 | (20.7) | 13.3 | (22.4) | 5.8 | (14.9) | |

| Student t test | .43 | .57 | .33 | .64 | |||||

| Diarrhea† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 12.5 | (22.3) | 9.2 | (22.6) | 15.8 | (28.2) | 10.8 | (25.5) | |

| Control | 20.8 | (32.7) | 17.5 | (23.9) | 24.2 | (32.9) | 18.3 | (27.2) | |

| Student t test | .19 | .11 | .23 | .21 | |||||

| HADS | |||||||||

| Anxiety† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 19.0 | (1.8) | 19.2 | (2.0) | 19.6 | (2.4) | 20.3 | (2.0) | t0→ t3: < .01*** |

| Control | 19.3 | (2.2) | 19.2 | (2.3) | 19.5 | (1.6) | 19.0 | (2.5) | ANOVA: interaction (P ≤ .01***) |

| Student t test | .43 | .96 | .74 | .01 | ** | ||||

| Depression† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 15.8 | (1.4) | 15.4 | (1.5) | 15.1 | (2.0) | 15.6 | (1.7) | |

| Control | 16.3 | (1.4) | 16.1 | (1.6) | 15.8 | (2.1) | 16.4 | (2.3) | |

| Student t test | .16 | .05 | .15 | .07 | |||||

| POMS | |||||||||

| Depression† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 13.8 | (13.1) | 13.9 | (12.9) | 11.4 | (12.0) | 11.0 | (13.0) | t2→ t3: .04** |

| Control | 16.9 | (15.7) | 17.7 | (16.8) | 13.0 | (12.1) | 17.3 | (15.7) | |

| Student t test | .33 | .26 | .55 | .05 | |||||

| Vigor | |||||||||

| Exercise | 22.8 | (7.0) | 21.5 | (8.5) | 20.83 | (8.9) | 22.8 | (9.9) | |

| Control | 20.5 | (9.5) | 20.3 | (8.7) | 18.49 | (9.1) | 20.2 | (9.9) | |

| Student t test | .22 | .53 | .25 | .25 | |||||

| Fatigue† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 15.1 | (8.4) | 13.9 | (9.2) | 15.0 | (8.7) | 12.8 | (9.2) | t0→ t2: .03** |

| Control | 15.2 | (10.0) | 15.5 | (11.7) | 20.3 | (10.1) | 19.5 | (10.6) | t0→ t3: < .01*** |

| Student t test | 0.96 | .48 | .01 | ** | < .01 | *** | ANOVA: interaction (P = 02**) | ||

| Anger/hostility† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 7.5 | (7.8) | 5.8 | (6.8) | 4.8 | (6.4) | 6.0 | (7.1) | t0→ t2: .02** |

| Control | 6.5 | (7.4) | 6.6 | (7.9) | 7.7 | (8.5) | 9.1 | (8.2) | t0→ t3: .02** |

| Student t test | .54 | .64 | .07 | .08 | ANOVA: interaction (P = .03**) | ||||

| NCCN distress thermometer | |||||||||

| Distress† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 4.6 | (2.2) | 4.2 | (1.9) | 3.4 | (2.2) | 3.2 | (2.2) | |

| Control | 4.8 | (2.9) | 4.3 | (3.0) | 4.6 | (2.8) | 4.0 | (2.6) | |

| Student t test | .83 | .93 | .05 | ** | .14 | ||||

| 6MWD | |||||||||

| Exercise | 539 | (88) | 553 | (87) | 472 | (88) | 538 | (80) | t0→ t3: < .01*** |

| Control | 544 | (107) | 546 | (106) | 445 | (112) | 490 | (103) | ANOVA: interaction (P = .02**) |

| Student t test | .80 | .77 | .24 | .02 | ** | ||||

| Strength (upper extremities) | |||||||||

| Exercise | 152.7 | (46.8) | 155.5 | (50.6) | 134.7 | (48.9) | 132.3 | (36.8) | |

| Control | 155.4 | (54.7) | 154.5 | (51.0) | 127.0 | (44.0) | 124.9 | (46.2) | |

| Student t test | .814 | .931 | .469 | .44 | |||||

| Strength (lower extremities) | |||||||||

| Exercise | 185.5 | (54.8) | 192.7 | (65.9) | 168.8 | (61.0) | 167.8 | (49.5) | t0→ t2: .03** |

| Control | 186.7 | (63.2) | 186.7 | (61.9) | 149.3 | (52.1) | 149.3 | (58.7) | |

| Student t test | .93 | .68 | .13 | .14 | |||||

| Coordination (one-leg stand and balancing) | |||||||||

| Exercise | 5.8 | (2.2) | 5.7 | (2.0) | 4.9 | (2.2) | 5.4 | (2.3) | |

| Control | 5.4 | (2.7) | 5.2 | (2.4) | 3.9 | (2.6) | 4.5 | (2.9) | |

| Student t test | .54 | .25 | .10 | .15 | |||||

| Pedometer steps, n | |||||||||

| Exercise | 5131 | (2813) | —§ | — | 3342 | (1247) | |||

| Control | 5363 | (2615) | — | — | 3934 | (1894) | |||

| Student t test | .76 | .20 | |||||||

| . | t0 (medical checkup before HSCT) . | t1 (admission to hospital) . | t2 (discharge from hospital) . | t3 (6-8 weeks after discharge) . | Significant changes over time* . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFI | |||||||||

| General fatigue† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 12.0 | (4.0) | 11.2 | (4.2) | 12.7 | (3.6) | 11.0 | (4.1) | t0→ t2: .01*** |

| Control | 11.6 | (4.7) | 11.4 | (4.7) | 14.7 | (4.4) | 13.5 | (4.3) | t0→ t3: < .01*** |

| Student t test | .72 | .82 | .03 | ** | < .01 | *** | ANOVA: interaction (P ≤ .01***)‡ | ||

| Physical fatigue† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 12.4 | (4.2) | 11.5 | (4.1) | 12.9 | (4.1) | 11.4 | (4.7) | t0→ t2: .02** |

| Control | 11.5 | (5.0) | 11.2 | (4.8) | 14.6 | (4.7) | 14.0 | (4.5) | t0→ t3: < .01** |

| Student t test | .41 | .78 | .08 | .01 | ** | ANOVA: interaction (P ≤ .01***)‡ | |||

| Reduced activation† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 10.6 | (4.2) | 10.8 | (4.2) | 12.9 | (4.1) | 12.0 | (4.5) | |

| Control | 11.4 | (4.9) | 11.5 | (4.1) | 13.5 | (4.2) | 12.5 | (4.1) | |

| Student t test | .40 | .47 | .52 | .60 | |||||

| Reduced motivation† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 7.7 | (3.1) | 7.5 | (3.1) | 8.5 | (3.5) | 8.2 | (3.5) | |

| Control | 8.3 | (3.2) | 8.6 | (3.5) | 9.0 | (3.5) | 8.6 | (3.5) | |

| Student t test | .38 | .16 | .52 | .64 | |||||

| Mental fatigue† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 9.0 | (4.3) | 9.1 | (3.9) | 10.3 | (4.6) | 10.2 | (4.2) | |

| Control | 10.0 | (4.3) | 10.6 | (4.2) | 10.9 | (4.1) | 10.2 | (3.9) | |

| Student t test | .31 | .12 | .51 | .99 | |||||

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | |||||||||

| QoL | |||||||||

| Exercise | 60.8 | (18.8) | 64.2 | (20.3) | 53.8 | (19.9) | 61.7 | (22.2) | |

| Control | 55.6 | (21.6) | 62.7 | (23.2) | 47.3 | (18.1) | 57.1 | (17.3) | |

| Student t test | .25 | .77 | .13 | .30 | |||||

| Physical functioning | |||||||||

| Exercise | 74.5 | (15.4) | 75.2 | (18.5) | 63.3 | (22.5) | 73.7 | (19.6) | t1→ t3: .02** |

| Control | 71.0 | (24.5) | 76.0 | (23.8) | 53.5 | (25.1) | 63.5 | (22.2) | |

| Student t test | .45 | .86 | .07 | .03 | ** | ||||

| Role functioning | |||||||||

| Exercise | 52.5 | (28.1) | 53.8 | (31.9) | 31.7 | (29.4) | 45.0 | (28.5) | |

| Control | 53.8 | (35.7) | 56.3 | (36.9) | 33.3 | (34.8) | 43.8 | (32.8) | |

| Student t test | .86 | .75 | .82 | .87 | |||||

| Emotional functioning | |||||||||

| Exercise | 57.1 | (24.6) | 62.5 | (24.2) | 62.3 | (25.3) | 70.0 | (24.2) | |

| Control | 58.1 | (24.6) | 60.6 | (26.3) | 59.2 | (22.0) | 60.5 | (25.1) | |

| Student t test | .85 | .74 | .57 | .09 | |||||

| Cognitive functioning | |||||||||

| Exercise | 75.8 | (25.0) | 77.1 | (23.8) | 69.6 | (26.7) | 73.8 | (22.3) | |

| Control | 70.4 | (27.6) | 70.0 | (30.7) | 62.1 | (28.0) | 71.3 | (19.6) | |

| Student t test | .36 | .25 | .22 | .60 | |||||

| Social functioning | |||||||||

| Exercise | 50.0 | (30.7) | 49.6 | (32.1) | 43.8 | (31.3) | 49.2 | (32.5) | |

| Control | 49.6 | (33.2) | 53.8 | (31.5) | 42.1 | (29.2) | 46.7 | (29.3) | |

| Student t test | .95 | .56 | .81 | .72 | |||||

| Fatigue† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 45.0 | (24.4) | 39.2 | (26.3) | 60.3 | (28.5) | 49.7 | (28.9) | |

| Control | 46.1 | (32.2) | 41.4 | (31.2) | 66.4 | (27.4) | 60.8 | (29.2) | |

| Student t test | .86 | .73 | .33 | .09 | |||||

| Nausea and vomiting† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 9.6 | (16.8) | 7.1 | (13.6) | 24.2 | (31.8) | 13.8 | (22.3) | |

| Control | 10.4 | (19.1) | 8.8 | (19.2) | 27.1 | (28.2) | 19.2 | (26.6) | |

| Student t test | .84 | .66 | .67 | .33 | |||||

| Pain† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 23.8 | (28.2) | 29.6 | (29.6) | 32.1 | (32.8) | 25.0 | (31.8) | t1→ t3: < .01*** |

| Control | 25.8 | (33.3) | 20.0 | (27.8) | 35.4 | (29.3) | 35.8 | (28.9) | ANOVA: interaction (P = .04**) |

| Student t test | .76 | .14 | .63 | .12 | |||||

| Dyspnea† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 34.2 | (28.7) | 26.7 | (28.4) | 39.2 | (28.1) | 30.0 | (25.9) | |

| Control | 30.8 | (32.4) | 28.3 | (33.4) | 42.5 | (34.6) | 33.3 | (31.1) | |

| Student t test | .63 | .81 | .64 | .60 | |||||

| Insomnia† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 34.2 | (32.5) | 30.8 | (31.5) | 51.7 | (36.9) | 30.8 | (32.4) | |

| Control | 35.0 | (36.2) | 32.5 | (32.5) | 52.5 | (33.7) | 35.8 | (31.5) | |

| Student t test | .91 | .82 | .92 | .49 | |||||

| Appetite loss† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 22.5 | (28.6) | 15.0 | (27.2) | 48.3 | (38.5) | 31.7 | (35.4) | |

| Control | 24.2 | (31.1) | 21.7 | (33.4) | 60.0 | (30.4) | 42.5 | (37.7) | |

| Student t test | .80 | .33 | .14 | .19 | |||||

| Constipation† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 14.2 | (23.7) | 10.0 | (18.8) | 8.3 | (23.6) | 4.2 | (17.2) | |

| Control | 10.0 | (22.9) | 7.5 | (20.7) | 13.3 | (22.4) | 5.8 | (14.9) | |

| Student t test | .43 | .57 | .33 | .64 | |||||

| Diarrhea† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 12.5 | (22.3) | 9.2 | (22.6) | 15.8 | (28.2) | 10.8 | (25.5) | |

| Control | 20.8 | (32.7) | 17.5 | (23.9) | 24.2 | (32.9) | 18.3 | (27.2) | |

| Student t test | .19 | .11 | .23 | .21 | |||||

| HADS | |||||||||

| Anxiety† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 19.0 | (1.8) | 19.2 | (2.0) | 19.6 | (2.4) | 20.3 | (2.0) | t0→ t3: < .01*** |

| Control | 19.3 | (2.2) | 19.2 | (2.3) | 19.5 | (1.6) | 19.0 | (2.5) | ANOVA: interaction (P ≤ .01***) |

| Student t test | .43 | .96 | .74 | .01 | ** | ||||

| Depression† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 15.8 | (1.4) | 15.4 | (1.5) | 15.1 | (2.0) | 15.6 | (1.7) | |

| Control | 16.3 | (1.4) | 16.1 | (1.6) | 15.8 | (2.1) | 16.4 | (2.3) | |

| Student t test | .16 | .05 | .15 | .07 | |||||

| POMS | |||||||||

| Depression† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 13.8 | (13.1) | 13.9 | (12.9) | 11.4 | (12.0) | 11.0 | (13.0) | t2→ t3: .04** |

| Control | 16.9 | (15.7) | 17.7 | (16.8) | 13.0 | (12.1) | 17.3 | (15.7) | |

| Student t test | .33 | .26 | .55 | .05 | |||||

| Vigor | |||||||||

| Exercise | 22.8 | (7.0) | 21.5 | (8.5) | 20.83 | (8.9) | 22.8 | (9.9) | |

| Control | 20.5 | (9.5) | 20.3 | (8.7) | 18.49 | (9.1) | 20.2 | (9.9) | |

| Student t test | .22 | .53 | .25 | .25 | |||||

| Fatigue† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 15.1 | (8.4) | 13.9 | (9.2) | 15.0 | (8.7) | 12.8 | (9.2) | t0→ t2: .03** |

| Control | 15.2 | (10.0) | 15.5 | (11.7) | 20.3 | (10.1) | 19.5 | (10.6) | t0→ t3: < .01*** |

| Student t test | 0.96 | .48 | .01 | ** | < .01 | *** | ANOVA: interaction (P = 02**) | ||

| Anger/hostility† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 7.5 | (7.8) | 5.8 | (6.8) | 4.8 | (6.4) | 6.0 | (7.1) | t0→ t2: .02** |

| Control | 6.5 | (7.4) | 6.6 | (7.9) | 7.7 | (8.5) | 9.1 | (8.2) | t0→ t3: .02** |

| Student t test | .54 | .64 | .07 | .08 | ANOVA: interaction (P = .03**) | ||||

| NCCN distress thermometer | |||||||||

| Distress† | |||||||||

| Exercise | 4.6 | (2.2) | 4.2 | (1.9) | 3.4 | (2.2) | 3.2 | (2.2) | |

| Control | 4.8 | (2.9) | 4.3 | (3.0) | 4.6 | (2.8) | 4.0 | (2.6) | |

| Student t test | .83 | .93 | .05 | ** | .14 | ||||

| 6MWD | |||||||||

| Exercise | 539 | (88) | 553 | (87) | 472 | (88) | 538 | (80) | t0→ t3: < .01*** |

| Control | 544 | (107) | 546 | (106) | 445 | (112) | 490 | (103) | ANOVA: interaction (P = .02**) |

| Student t test | .80 | .77 | .24 | .02 | ** | ||||

| Strength (upper extremities) | |||||||||

| Exercise | 152.7 | (46.8) | 155.5 | (50.6) | 134.7 | (48.9) | 132.3 | (36.8) | |

| Control | 155.4 | (54.7) | 154.5 | (51.0) | 127.0 | (44.0) | 124.9 | (46.2) | |

| Student t test | .814 | .931 | .469 | .44 | |||||

| Strength (lower extremities) | |||||||||

| Exercise | 185.5 | (54.8) | 192.7 | (65.9) | 168.8 | (61.0) | 167.8 | (49.5) | t0→ t2: .03** |

| Control | 186.7 | (63.2) | 186.7 | (61.9) | 149.3 | (52.1) | 149.3 | (58.7) | |

| Student t test | .93 | .68 | .13 | .14 | |||||

| Coordination (one-leg stand and balancing) | |||||||||

| Exercise | 5.8 | (2.2) | 5.7 | (2.0) | 4.9 | (2.2) | 5.4 | (2.3) | |

| Control | 5.4 | (2.7) | 5.2 | (2.4) | 3.9 | (2.6) | 4.5 | (2.9) | |

| Student t test | .54 | .25 | .10 | .15 | |||||

| Pedometer steps, n | |||||||||

| Exercise | 5131 | (2813) | —§ | — | 3342 | (1247) | |||

| Control | 5363 | (2615) | — | — | 3934 | (1894) | |||

| Student t test | .76 | .20 | |||||||

Data are mean (SD).

MFI indicates Multidimensional Fatigue Index; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Questionnaire; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; and ANOVA, analysis of variance

Comparisons of measurement point differences between groups (Student t test) and/or ANOVA effects (time by group); **, significant; ***, highly significant.

Lower scores are beneficial.

Statistically significant after Bonferroni correction.

No assessment during hospitalization.

For secondary outcomes, significant group differences were observed for EORTC “physical functioning” (P = .03) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale “anxiety” (P = .01) at the end of Intervention (t3), where “physical functioning” was higher and “anxiety” also higher in the exercise group and a significant interaction effect (group by time) was observed (P = .007). In contrast to higher anxiety, global distress was significantly reduced in the exercise group at the time of discharge from the hospital (P = .05). Comparing pre-post group mean differences, significant improvements were shown for the exercise group in POMS subscale “Anger/Hostility” (P = .02 [baseline → t2]; P = .02 [baseline → t3]; interaction effect, P = .03) and EORTC subscale “pain” (P = .007 [admission to hospital → t3]; interaction effect, P = .04).

Physical capacity endpoints are summarized in the lower part of Table 4. Patients in the exercise group reached significantly more meters in the 6-minute walk test at t3 (P = .02) and comparing pre-post mean differences (baseline → t3; P = .006). Variance analysis furthermore showed a significant main effect for time (P < .001) but not for group (P = .30) and an interaction effect between time and group (P = .02). The intervention significantly improved the strength of the lower extremities (baseline → t2, P = .03). No differences were observed in pedometer steps and coordination tasks. Physical capacity was significantly inversely correlated with general fatigue (P < .01-.02; Table 5).

Pearson correlation coefficients for physical capacity and fatigue

| . | Baseline (t0) . | Study end (t3) . |

|---|---|---|

| General fatigue and 6MWD | −0.36 (P = .001) | −0.48 (P < .001) |

| General fatigue and upper strength | −0.30 (P = .008) | −0.26 (P = .02) |

| General fatigue and lower strength | −0.29 (P = .009) | −0.39 (P < .001) |

| . | Baseline (t0) . | Study end (t3) . |

|---|---|---|

| General fatigue and 6MWD | −0.36 (P = .001) | −0.48 (P < .001) |

| General fatigue and upper strength | −0.30 (P = .008) | −0.26 (P = .02) |

| General fatigue and lower strength | −0.29 (P = .009) | −0.39 (P < .001) |

Discussion

This is the first investigation of the effects of a physical exercise program before, during, and after allo-HSCT focusing on cancer-related fatigue. Furthermore, with 112 included patients (105 starting), the current study is one of the largest RCTs of allo-HSCT and physical exercise. The control group had the same dose of social contact, a key consideration when studying cancer-related fatigue35 and QoL36 in the context of HSCT.37

Our study demonstrates that a partly supervised exercise intervention that is initiated before HSCT and continues after discharge significantly reduced cancer-related fatigue and improves the secondary outcome parameters physical capacity, functioning, anger/hostility, pain, and global distress, which are the most common and impairing adverse effects of allo-HSCT besides GVHD.3-5

Recent studies have demonstrated that aerobic exercise is a potentially important intervention against cancer-related fatigue in general.38 Our results extend these findings to the population of allo-HSCT patients, by use of a combined endurance and resistance training. In our trial, we observed significant improvements at discharge and at the end of the exercise intervention. Regarding the minimal clinically important differences in cancer-related fatigue scores reported for the different MFI subscales in cancer patients by Purcell et al,39 our fatigue findings concerning “general fatigue” and “physical fatigue” can be regarded as clinically important and relevant. Previous studies on exercise and cancer-related fatigue have shown benefits in some, although not all, settings. For example, Carlson et al12 and Wilson et al17 reported significant improvements in fatigue in noncontrolled studies after HSCT. However, other RCTs reported no effects on fatigue during HSCT.11,14,33

Jarden et al19 showed that their multimodal intervention program (exercise combined with psycho-educational and relaxing components) had positively influenced the cognitive symptom cluster (fatigue is included) during hospitalization. But because of the integrated nonexercise intervention parts (progressive relaxation and psycho-education) and clustering of symptoms, an exact association between exercise and fatigue is not possible. In contrast, our correlation data support the important link between physical fitness and severity of fatigue as shown in other previous non-HSCT studies.40,41 Focusing on the multidimensional subscales of the MFI, a selective influence of the intervention program is conspicuous. So there is apparently a significant impact on the physical dimension of fatigue but no effect on cognitive aspects. These data are consistent with previous finding reported from the group of Dimeo et al in patients with hematologic or solid tumor diseases exercising after medical treatment.42

In our study, physical functioning was significantly improved in the training group, and emotional functioning showed a similar trend. These results are in accordance with published data of DeFor et al16 who applied a 100-day walking regimen for patients after allo-HSCT. However, for depression (which is a closely fatigue-linked symptom), both scales used in our study (POMS and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) showed only suggestive benefits in the intervention group. Contrary to Dimeo et al,33 our data cannot confirm the reported positive exercise-induced effect on patients' anxiety levels. Conversely, the exercise group was significantly more anxious than the control group on completion of the study. A potential explanation could be anxiety caused by the end of the exercise intervention and resulting diminished care by study personnel. On the other hand, patients in the exercise group showed reduced anger/hostility. Consistent with Dimeo et al43 and Jarden et al,19 our study also supports a positive influence of exercise on perceived pain during and after hospitalization.

Compared with the control group, endurance capacity in allo-HSCT patients in the exercise group also improved significantly, although more modestly than in prior studies, which performed fully supervised exercise programs during the inpatient setting.11,14 Nevertheless, these results are considerable for a predominantly self-directed exercise program. Our patient population showed only statistically significant improvements for lower extremity strength parameters, with a nonsignificant increase in all strength parameters over the course of the study. Stronger effects for the lower extremity strength might be explained by the endurance training, which was predominantly walking or bicycling.

This study had several strengths. It is the first to test an exercise intervention before, during, and after allo-HSCT. Intervention benefits were observed during all periods, yet the inpatient period seemed to be the most effective. The reported recruitment rate (79.4%) is high and comparable with other reports (91%14 ; 90%43 ; 74%17 ). Adherence was good and comparable with other studies.14,17,33,44 In addition, only 2 patients withdrew from the study, confirming the high commitment of HSCT patients to exercise interventions that may improve their outcome.10 All participants, even the control group, had access to exercise equipment (eg, stationary bicycles in each isolation unit), which was not standard in other studies.14 A recent Cochrane review45 supports our intervention design by stating that partly self-directed programs are the most effective way to develop a stable physical activity behavior. The intervention was self-administered, required minimal reinforcement from a professional, and needed no special or expensive equipment.

Our study also had limitations. Concerning testing methodology, the 6MWT is not the state-of-the-art procedure for assessing endurance capacity. A procedure including cardiorespiratory exercise testing to determine maximal oxygen uptake46 would be desirable but is not practical in the setting of a multicenter study and multiple testing before, during, and after allo-HSCT. Furthermore, the 6MWT is a valid, reliable, and comparable and often used testing procedure in clinical trials.47,48 Intertester reliability might be a problem for use of handheld dynamometers.49 To cope with this problem, only one tester per patient performed all highly standardized assessments. The testers were not blinded to randomization but not involved in the therapeutic supervision of the patients. Another limitation was the number of missing exercise logs, which limited our assessment of adherence, mostly before and during the inpatient period. In addition, we did not conduct structured documentation about social support regarding exercise training nor the patients' “exercise infrastructure” and facilities at their homes. Finally, the study results may be impacted by the comparison with a quite active control group (wearing pedometers whose use has been shown to increase physical activity50 ). This would reduce the observed effect sizes.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that physical exercise is feasible and beneficial for patients before, during, and after allo-HSCT, even if the intervention is only partly supervised. It could be shown that an exercise intervention can significantly alter cancer-related fatigue in the context of allo-HSCT. Furthermore, physical performance and functioning as well as other distress parameters improved. Because of its low personnel effort (only partly supervised training during and telephone calling before and after hospitalization), the here tested exercise intervention can be easily integrated into standard supportive medical care.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the German José Carreras Leukemia Foundation (2006-2008; project no. R05/33p).

Authorship

Contribution: J.W. drafted and finalized the manuscript; J.W., G.H., and M.B. designed and performed the study; A.B. recruited study participants; N.K. and J.W. performed statistical analysis of the data; P.D., R.S., and M.B. provided medical expertise and critically reviewed the paper; and C.M.U. critically reviewed the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Joachim Wiskemann, National Center for Tumor Diseases, Division of Preventive Oncology, Im Neuenheimer Feld 460, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; e-mail: joachim.wiskemann@nct-heidelberg.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal