Abstract

The limited effects of current treatments of primary myelofibrosis (PM) led us to prospectively evaluate recombinant interferon-α (rIFNα) in “early” PM patients with residual hematopoiesis and only grade 1 or 2 myelofibrosis. Seventeen patients meeting World Health Organization PM diagnostic criteria received either rIFNα-2b 500 000 to 3 million units 3 times weekly, or pegylated rIFNα-2a 45 or 90 μg weekly. International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment criteria for prognosis and response were used. Eleven patients were women and 6 were men. Their median age at diagnosis was 57 years. Eleven patients were low risk and 6 were intermediate-1 risk. Two achieved complete remission, 7 partial, 1 clinical improvement, 4 stable disease, and 3 had progressive disease. Thus, more than 80% derived clinical benefit or stability. Improvement in marrow morphology occurred in 4. Toxicity was acceptable. These results, with documented marrow reversion because of interferon treatment, warrant expanded evaluation.

Introduction

Limitations of conventional treatment, JAK2 inhibitors, and stem cell transplantation in primary myelofibrosis (PM)1-4 led us to explore recombinant interferon-α (rIFNα) in “early” PM, when there is residual hematopoiesis and only grade 1 or 2 fibrosis. This use of rIFNα is based on its effectiveness in treating polycythemia vera with fibrosis5-8 and its biologic effects on megakaryopoiesis and hematopoietic stem cells.9 It is agreed that rIFNα is not beneficial in advanced PM, when the marrow is extensively fibrotic and/or osteosclerotic without residual hematopoietic cells.10,11 Thus, the use of rIFNα in early PM10-13 is not competitive with Janus kinase inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs, which are used in advanced PM.1-3 We previously described preliminary results of rIFNα-2b therapy in 13 patients with early PM,14 of whom 4 had documented significant marrow change. We now report updated, detailed results of this prospective, single-center analysis, expanded to include 17 patients, of whom 3 received pegylated rIFNα-2a (peg-IFNα-2a) therapy.

Methods

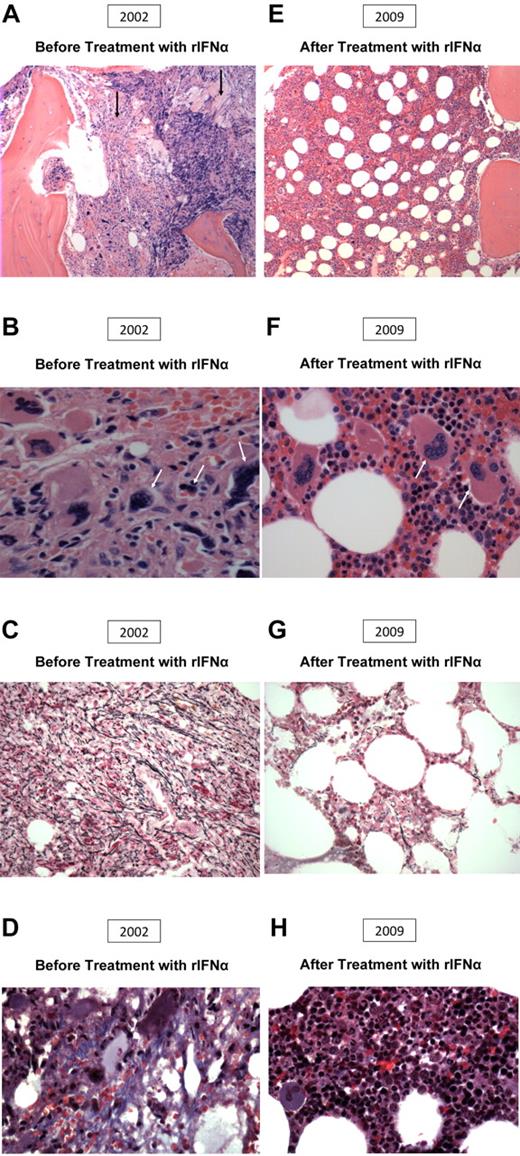

Diagnosis was established using World Health Organization criteria for PM.15 Marrow specimens were stained with hematoxylin-eosin, Giemsa, and for reticulin and collagen. Fibrosis was graded using Manoharan criteria.16 Patients with grade 3 or 4 reticulin were excluded.16 Included patients had residual erythropoietic foci occupying ≥ 30% of the marrow biopsy (Figure 1A).

Morphologic change after IFN therapy in a patient with primary myelofibrosis. (A-D) Before treatment (2002). (A) The area of myelofibrosis (left), with preserved residual foci of hematopoiesis, and abnormal megakaryocyte morphology (right). (B) Abnormal megakaryocyte morphology. (C) 2+ reticulin fibrosis. (D) Collagen fibrosis. (E-H) After treatment (2009). (E) Improved bone marrow architecture, hematopoiesis, and megakaryocyte morphology. (F) Improved megakaryocyte morphology and increased normoblastic erythropoiesis. (G) Minimal reticulin fibrosis. (H) Absent collagen fibrosis.

Morphologic change after IFN therapy in a patient with primary myelofibrosis. (A-D) Before treatment (2002). (A) The area of myelofibrosis (left), with preserved residual foci of hematopoiesis, and abnormal megakaryocyte morphology (right). (B) Abnormal megakaryocyte morphology. (C) 2+ reticulin fibrosis. (D) Collagen fibrosis. (E-H) After treatment (2009). (E) Improved bone marrow architecture, hematopoiesis, and megakaryocyte morphology. (F) Improved megakaryocyte morphology and increased normoblastic erythropoiesis. (G) Minimal reticulin fibrosis. (H) Absent collagen fibrosis.

Prognosis and response were assessed using International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment criteria.17-19 Inclusion categories were low-risk and intermediate-1 risk. Response classifications included: complete response (CR), partial response (PR), clinical improvement (CI), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD).

After obtaining informed consent, baseline evaluations were performed, including history, physical examination, complete blood count, differential, serum chemistries, liver, renal, and thyroid function tests, bone marrow biopsy, BCR-ABL determination, cytogenetic evaluation, and JAK2 analysis. Spleen size was measured in centimeters below the left costal margin. Contraindications to rIFNα included depression, neuropathy, thyroid dysfunction, autoimmune disease, and significant hepatic, renal, or cardiac abnormalities. JAK2 genotyping was performed according to described methods.20,21 Sequential JAK2V617F responses were evaluated using European LeukemiaNet criteria.22 Categories included complete, partial, and no molecular response.

We evaluated 62 patients meeting World Health Organization PM criteria, of whom 44 were excluded because of marked marrow fibrosis. The remaining 18 patients (29%) met study inclusion criteria; 17 elected IFN therapy. Eleven were women and 6 were men. None had received prior PM therapy except aspirin. None were transfusion dependent. Their median age at diagnosis was 57 years (range, 36-71 years).

Fourteen received rIFNα-2b 500 000 to 1 million units subcutaneously 3 times weekly, gradually increasing to 2 million to 3 million units 3 times weekly as tolerated and, if necessary, to reduce spleen size, which was used as a clinical indicator of response. Three patients received 45 or 90 μg of peg-IFNα-2a weekly because of patient preference and insurance coverage. Patients were evaluated at 2- to 3-month intervals. Marrow biopsy was attempted annually. Toxicity was assessed using the Common Terminology Criteria, Version 3.0. We subsequently administered the minimum dose of therapy to achieve the maximum effect. Dose adjustments were made by taking into account resolution of splenomegaly, and toxicity, if present. Study period and therapy duration were equivalent: median, 3.3 years (range, 0.5-15.0 years). One patient in our original report,14 who had a marrow remission after 1 year, received subsequent care elsewhere. Because appropriate follow-up data could not be obtained, this patient was excluded from the analysis.

Results and discussion

Eleven patients were low-risk and 6 were intermediate-1 risk (Table 1). Responses were seen in both categories. Two achieved CR, 7 PR, 1 CI, 4 SD, and 3 PD. Ten (58.8%) derived clinical benefit, and another 4 (23.5%) disease stability. Thus, > 80% derived clinical benefit or stability. Seven of 11 low-risk patients (63.6%), and 3 of 6 intermediate-1 risk patients (50.0%) showed clinical benefit. Three of 11 low-risk patients (27.3%) and 1 of 6 intermediate-1 risk patients (16.7%) had disease stability. The median time to any documented response was 1.0 year (range, 0.4-7.4 years); the median duration after any documented response has been 2.0 years (range, 0.1-14.0 years).

Assessment of prognosis and response

| Baseline IWG-MRT prognostic risk group . | rIFNα duration, y . | IWG-MRT response type . | Histologic bone marrow response? (yes/no) . | Spleen size before therapy, cm . | Spleen size at last follow-up, cm . | JAK2V617F (initial), % . | JAK2V617F (final), % . | Molecular response§ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low* | 7.6 | CR | Yes | 2 | 0 | ND | ND | None |

| Low | 5.2 | PR | No BM follow-up | 1 | 0 | ND | NA | NA |

| Low | 7.8 | PR | No | 0 | 0 | 9.7 | 14.3 | None |

| Low | 1.8 | PR | Yes | 12 | 0 | 33.2 | 38.0 | None |

| Low | 2.3 | PR | No | 16 | 0 | 75.4 | 52.0 | Partial |

| Low | 0.5† | PR | No | 2 | 0 | 20.5 | 18.3 | None |

| Low* | 4.7 | CI | No | 10 | 0.5 | 34.9 | 29.9 | None |

| Low | 0.8 | SD | No | 11 | 10 | 85.8 | 87.1 | None |

| Low* | 15.0 | SD | No | 7 | 0 | ND | ND | None |

| Low | 2.0‡ | SD | No | 2 | 0 | ND | ND | None |

| Low | 3.2 | PD | No | 7 | 11 | 2.0 | 18.0 | None |

| Intermediate-1 | 4.5 | CR | Yes | 3 | 0 | 10.7 | 5.3 | Partial |

| Intermediate-1 | 4.5 | PR | No | 0 | 0 | 45.6 | 24.1 | None |

| Intermediate-1 | 3.3† | PR | Yes | 3 | 0 | 10.1 | 8.0 | None |

| Intermediate-1 | 2.9 | SD | No BM follow-up | 24 | 16 | 88.1 | 89.0 | None |

| Intermediate-1* | 5.4 | PD | No | 16 | 20 | ND | ND | None |

| Intermediate-1* | 2.4† | PD | No | 32 | 24 | 64.2 | 50.4 | None |

| Baseline IWG-MRT prognostic risk group . | rIFNα duration, y . | IWG-MRT response type . | Histologic bone marrow response? (yes/no) . | Spleen size before therapy, cm . | Spleen size at last follow-up, cm . | JAK2V617F (initial), % . | JAK2V617F (final), % . | Molecular response§ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low* | 7.6 | CR | Yes | 2 | 0 | ND | ND | None |

| Low | 5.2 | PR | No BM follow-up | 1 | 0 | ND | NA | NA |

| Low | 7.8 | PR | No | 0 | 0 | 9.7 | 14.3 | None |

| Low | 1.8 | PR | Yes | 12 | 0 | 33.2 | 38.0 | None |

| Low | 2.3 | PR | No | 16 | 0 | 75.4 | 52.0 | Partial |

| Low | 0.5† | PR | No | 2 | 0 | 20.5 | 18.3 | None |

| Low* | 4.7 | CI | No | 10 | 0.5 | 34.9 | 29.9 | None |

| Low | 0.8 | SD | No | 11 | 10 | 85.8 | 87.1 | None |

| Low* | 15.0 | SD | No | 7 | 0 | ND | ND | None |

| Low | 2.0‡ | SD | No | 2 | 0 | ND | ND | None |

| Low | 3.2 | PD | No | 7 | 11 | 2.0 | 18.0 | None |

| Intermediate-1 | 4.5 | CR | Yes | 3 | 0 | 10.7 | 5.3 | Partial |

| Intermediate-1 | 4.5 | PR | No | 0 | 0 | 45.6 | 24.1 | None |

| Intermediate-1 | 3.3† | PR | Yes | 3 | 0 | 10.1 | 8.0 | None |

| Intermediate-1 | 2.9 | SD | No BM follow-up | 24 | 16 | 88.1 | 89.0 | None |

| Intermediate-1* | 5.4 | PD | No | 16 | 20 | ND | ND | None |

| Intermediate-1* | 2.4† | PD | No | 32 | 24 | 64.2 | 50.4 | None |

BM indicates bone marrow; ND, not detected; and NA, not available.

Abnormal cytogenetics.

Received pegylated rIFNα-2a therapy.

Discontinued interferon.

According to European LeukemiaNet Criteria.

Median baseline leukocyte, hematocrit, hemoglobin, and platelet values were 8.7 ×1000/μL, 35.5%, 11.7 g/dL, and 404 000/μL, respectively. Median values at last follow-up were 5.7 ×1000/μL, 34.5%, 11.5 g/dL, and 270 000/μL, respectively, thus remaining relatively unchanged.

Nine of 15 patients with initial splenomegaly had complete resolution of splenomegaly. Fifteen of 17 patients had either sustained reduction in spleen size or no splenomegaly without progression (Table 1).

Marrow follow-up studies, possible in 15, were performed a median of 3.2 years (range, 0.9-7.6 years) after therapy start. Marrow morphology remained unchanged in 11 but significantly improved in 4 (2 CR and 2 PR) after a median of 3.0 years (range, 1.0-7.4 years). The median marrow response duration after documentation has been 1.9 years (range, 0.4-14.0 years). Marrow architecture, reticulin and collagen fibrosis, and megakaryocytic atypia significantly improved in all 4, and fibrosis and megakaryocytic atypia were virtually absent in 2 after 1.0 to 4.0 years (Figure 1E-H). In these 4 patients, sustained reduction in splenomegaly occurred. Three had normal cytogenetics, and 1 had trisomy 1q, which has persisted. Only 2 have had partial molecular response.

Of the 17 patients, sequential cytogenetic analyses were possible in 4 of 5 with abnormal cytogenetics and showed no evolution or resolution of these abnormalities. Sequential analyses, possible in 7 with initially normal karyotypes, did not change. Cytogenetic abnormalities were as previously described in PM.23,24 One patient with 20q− had PD.23-25 Except for this patient, contrary to other reports,23,24 neither favorable nor unfavorable cytogenetics correlated with treatment response or disease progression.

Quantitative JAK2V617F allele burden was assessed in 17 patients. Five of these 17 had wild-type and 12 had mutant forms of the JAK2 allele (median allele burden, 17 patients: 10.7%; range, 2.0%-88.1%). Of 16 with serial quantitative JAK2V617F analyses (average number of determinations = 3), 2 achieved partial molecular response and 14 no molecular response (Table 1).22 Importantly, there was no correlation between change in JAK2V617F allele burden and changes in spleen size or abnormal marrow morphology.

Toxicity was generally mild (grade 1 or 2), dose-related, and subsided or diminished on dose reduction. Eleven patients received continuous therapy, and 6 patients received intermittent therapy. Nine experienced systemic toxicity, 11 hematologic toxicity, and 10 metabolic toxicity. Systemic toxicity included the usual grade 1 or 2 adverse events (eg, asthenia, fatigue, myalgia), which did not require dose reduction. Seven experienced anemia (2 grade 1, 4 grade 2, and 1 grade 4). Five experienced thrombocytopenia (2 grade 1, 2 grade 2, and 1 grade 3). Three experienced grade 1 leukopenia. None required transfusion therapy during treatment with IFN. Nine had grade 1 or 2 liver function test abnormalities, which usually resolved spontaneously. Two experienced continuing slight hyperbilirubinemia. Three experienced grade 1 hypocalcemia, 1 of whom received peg-rIFNα-2a. One patient developed hyperthyroidism, requiring rIFNα-2b discontinuation. Of the 3 treated with peg-rIFNα-2a, 2 experienced grade 1 constitutional toxicity, whereas 1 developed grade 4 anemia and discontinued therapy.

In this small sample, it was difficult to assess quantitative differences between rIFNα-2b and peg-rIFNα-2a. One patient receiving peg-rIFNα-2a had a marrow response, and 2 had spleen responses. We think that the low molecular response rate in our peg-rIFNα-2a–treated patients may be related to short therapy duration (Table 1).7-9,12

This use of low-dose rIFNα in morphologically “early” PM, as defined, resulted in marrow reversion, regression of splenomegaly, and disease stabilization, with tolerable toxicity. Marrow improvement correlated with splenomegaly regression, suggesting that change in splenomegaly may be used to gauge potential marrow response. Although we, like others, have reported the clinical benefits of rIFNα,10-13 this is the first series of documented marrow responses with rIFNα therapy correlated with clinical improvement using new criteria for evaluation.19 These encouraging results warrant further systematic evaluation of IFN in early PM, which as yet remains an experimental therapy.

Presented in part at the 50th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, December 6, 2008.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lynn Wang, N. C. P. Cross, and Amy Jones for the determination of the JAK2V617F allele burden; Attilio Orazi, Wayne Tam, and Amy Chadburn for the independent review of the bone marrow biopsies; Susan Mathew and Vesna Najfeld for their cytogenetic evaluation; and Paul Christos for performing statistical analysis.

This work was supported by the William and Judy Higgins Trust and the Johns Family Fund of the Cancer Research and Treatment Fund Inc, New York, NY.

Authorship

Contribution: R.T.S. designed and performed the research, cared for the patients, analyzed the data, reviewed histopathology, and wrote the paper; and K.V. and J.J.G. collected and analyzed data and assisted with writing of the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests. None of the authors have any financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias this work. None of the authors received financial support from any pharmaceutical company manufacturing IFN. No supplies of IFN were requested from, offered, or granted by any pharmaceutical company.

This review of patients treated with IFN was approved by the Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Review Board.

Correspondence: Richard T. Silver, Weill Cornell Medical College, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Weill Greenberg Center, 1305 York Ave, 12th Fl, Rm Y-1216, Box 581, New York, NY 10021; e-mail: rtsilve@med.cornell.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal