Abstract

Hastening posttransplantation immune reconstitution is a key challenge in human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–haploidentical hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT). In experimental models of mismatched HSCT, T-regulatory cells (Tregs) when coinfused with conventional T cells (Tcons) favored posttransplantation immune reconstitution and prevented lethal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). In the present study, we evaluated the impact of early infusion of Tregs, followed by Tcons, on GVHD prevention and immunologic reconstitution in 28 patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies who underwent HLA-haploidentical HSCT. We show for the first time in humans that adoptive transfer of Tregs prevented GVHD in the absence of any posttransplantation immunosuppression, promoted lymphoid reconstitution, improved immunity to opportunistic pathogens, and did not weaken the graft-versus-leukemia effect. This study provides evidence that Tregs are a conserved mechanism in humans.

Introduction

A viable option for high-risk, acute leukemia patients without matched donors is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) from human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–haploidentical 3-loci–mismatched family members who were readily available for almost all patients.1,2 Until the 1990s, full-haplotype–mismatched, T cell–replete transplantations were unsuccessful because donor-alloreactive T cells triggered a high incidence of severe graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) despite posttransplantation immune suppression.3,4 The breakthrough came with the use of a megadoses of extensively ex vivo T cell–depleted peripheral blood hematopoietic progenitor cells and a highly myeloablative conditioning regimen containing antithymocyte globulin (ATG), which exerts additional T-cell depletion in vivo. This approach ensures a high rate of primary engraftment in the absence of GVHD,5 with more than 40% long-term event-free survival and excellent quality of life.1,2 However, extensive ex vivo and in vivo T-cell depletion delays the recovery of immune responses against pathogens, leading to a high incidence of life-threatening infections.1,2

Strategies to hasten posttransplantation immune reconstitution without triggering GVHD have included infusion of donor T cells after engineering with a suicide gene,6 photodynamic purging,7 and the use of an anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody (mAb)8 to remove alloreactive cells. An alternative strategy might be based on donor CD4+CD25+ T-regulatory cells (Tregs). In murine models of HSCT across major histocompatibility complex barriers, CD4+CD25+ Tregs suppressed lethal GVHD9 and favored posttransplantation immune reconstitution when coinfused with conventional T cells (Tcons).10

The main obstacle to clinical application of human Tregs is their paucity in the peripheral blood. Although ex vivo–expanded polyclonal11 or recipient-specific Tregs12 were proposed to circumvent this potential barrier, we opted for closed, automated immunoselection13 of naturally occurring Tregs. In the present study, for the first time in humans, we show that the early infusion of freshly isolated donor Tregs followed by Tcons at the time of full-haplotype–mismatched HSCT prevented GVHD while favoring Tcon-mediated posttransplantation immune reconstitution.

Methods

Study design, conditioning regimen, stem cell mobilization, and supportive care

In 2008, the Umbria Regional Hospital Ethics Committee (CEAS Umbria) approved the protocol entitled “Adoptive Immunotherapy with Natural Regulatory T cells (Treg) and Effector T Cells in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation from 2-3 Loci Mismatched HLA-Haploidentical Family Donors for Patients with High Risk Haematologic Malignancies” (Protocol No 01/08). Written informed consent was obtained for all patients and donors in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Inclusion criteria were: acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL) in remission at high risk of relapse; acute leukemia with primary induction failure, in chemoresistant relapse, or in relapse after autologous transplantation; high-grade Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma in relapse after 3 lines of chemotherapy and autologous transplantation; age range, 18-65 years of age; no major lung, liver, renal, or cardiac dysfunction; no major psychiatric disturbances; lack of an HLA-identical sibling or a matched, unrelated registry donor. Twenty-eight consecutive patients (11 male; 17 female; median age, 41; age range, 21-60) were enrolled. Twenty-two had AML (10 were in first complete remission [CR1], 10 were in ≥ second CR, and 2 were in relapse), 5 had ALL (4 were in CR1 and 1 was in relapse), and 1 had high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma in relapse. All patients who were transplanted in CR1 were at high risk of relapse (5 with FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3/internal tandem duplication, 3 with t(9:22), 2 with complex karyotypes, 1 with secondary AML, 1 biphenotypic, 1 CR after second-line induction, 1 with central nervous system and skin localization at diagnosis). Donor eligibility was having a family member with one haplotype identical to the patient's and the ability to donate hematopoietic stem cells after treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and undergo leukapheresis sessions for collecting hematopoietic stem cells, Tregs, and Tcons. Primary end points were: (1) to demonstrate that, in the HLA-haploidentical transplantation setting and without any posttransplantation immunosuppression, Tregs inhibit effector T-cell alloreactivity, thus eliminating the risk of GVHD; and (2) to demonstrate that Tregs do not cross-inhibit conventional pathogen-specific T-cell responses and that adoptive transfer of Tregs and Tcons hastens immune reconstitution. Secondary end points were: (1) to reduce the incidence and severity of bacterial, viral, and fungal infections and consequently transplantation-related mortality; and (2) to demonstrate that this strategy does not increase the incidence of posttransplantation leukemia relapse.

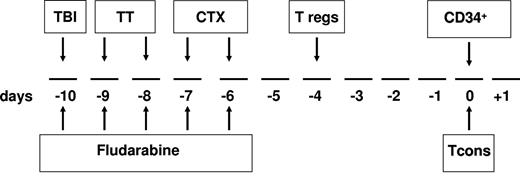

The transplantation timeline schema is shown in Figure 1. Briefly, the conditioning regimen included total body irradiation (8 Gy on a single fraction at a fast dose rate with lung shielding) on day −10; thiotepa (4 mg/kg/d) on days −10 and −9; fludarabine (40 mg/m2/d) from days −10 to −6; and cyclophosphamide (35 mg/kg/d) on days −7 and −6. After conditioning, patients received an infusion of freshly isolated donor Tregs (day −4). Immediately afterward, donors were treated with G-CSF to mobilize peripheral blood progenitor cells. After collection, CD34+ cells were positively immunoselected using the CliniMACS device (Miltenyi Biotec)1,2 and freshly infused on day 0 (mean CD34+ dose 9.4 × 106/kg ± 3.4 with a mean of 0.8 × 104/kg ± 0.4 contaminating T cells). On the same day, patients also received an infusion of Tcons that had been collected before donors were treated with G-CSF, separated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) by negative selection using CliniMACS CD19 reagent (Miltenyi Biotec), and cryopreserved. No posttransplantation GVHD prophylaxis was given.

Overall view of the protocol. The conditioning regimen included total body irradiation (TBI) of 8 Gy in a single fraction at 16 cGy/m, thiotepa (TT) at 4 mg/kg/d, cyclophosphamide (CTX) at 35 mg/kg/d, and fludarabine at 40 mg/sqm/d. On day −4, the patient received freshly isolated donor Tregs, followed by a megadose of CD34+ cells and Tcons (day 0). No posttransplantation immunosuppression was given.

Overall view of the protocol. The conditioning regimen included total body irradiation (TBI) of 8 Gy in a single fraction at 16 cGy/m, thiotepa (TT) at 4 mg/kg/d, cyclophosphamide (CTX) at 35 mg/kg/d, and fludarabine at 40 mg/sqm/d. On day −4, the patient received freshly isolated donor Tregs, followed by a megadose of CD34+ cells and Tcons (day 0). No posttransplantation immunosuppression was given.

The interval between the Treg and Tcon infusions was in accordance with animal data indicating that Tregs needed to be administered first to provide the greatest protection against GVHD.14

Even though in vitro assays showed that Tregs inhibited a mixed-lymphocyte reaction at a Tcon:Treg ratio of 1:2, for safety reasons, 0.5 × 106/kg of Tcons were administered with 2 × 106/kg Tregs in the first group of 4 patients. Onset of acute GVHD was the indication for stopping Tcon dose escalation. Because none of these 4 patients developed acute GVHD, Tcons were then escalated to 1 × 106/kg in the next 17 patients and Tregs remained unchanged. Tcons were increased to 2 × 106/kg in the last 5 patients who received 4 × 106/kg Tregs. Two patients did not receive Tcons because FoxP3+ expression in the Treg preparation was < 50%.

Patients were managed in positive-pressure airflow rooms. Red cell and platelet transfusions were given according to institutional policy. Prophylaxis against viral and fungal infections consisted of acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours daily) or ganciclovir (10 mg/kg/d) and liposomal amphotericin-B (2 mg/kg/d) from day −10 until the end of neutropenia. Prophylaxis after neutrophil recovery consisted of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (from day +50 until day +150) and acyclovir (until 6 months after HSCT).

Treg separation and analysis

After obtaining informed consent from donors, mononuclear cells were obtained by apheresis using a continuous-flow cell separator (SPECTRA; Cobe BCT). CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells were isolated using large-scale (CliniMACS; Miltenyi Biotec) separation systems. Clinical-grade reagents were used under Good Manufacturing Practice conditions. CD4+CD25+ Tregs were isolated in a 2-step procedure. Briefly, cells were washed, adjusted to 87.5 mL in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid)/2% human albumin (HA), labeled with CliniMACS CD8 and CD19 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec) for 30 minutes at room temperature on an orbital shaker, rewashed, and resuspended in 100 mL of PBS/EDTA/2% HA. CD8- and CD19-labeled cells were depleted by the 2.1 depletion program on the CliniMACS instrument (Miltenyi Biotec). The negative cell fraction was suspended in 190 mL of PBS/EDTA/2% HA, labeled with 7.5 mL of CD25 MicroBeads (CliniMACS) for 30 minutes at room temperature on an orbital shaker, washed, and resuspended in 100 mL of PBS/EDTA/2% HA. CD25+ cells were isolated by automatic positive-selection cycles using the 3.1 enrichment program on the CliniMACS device. Aliquots before and after each labeling, depletion, and enrichment step were immunophenotyped. Phenotypes were determined using direct immunofluorescence with a panel of mAbs directed against the following antigens: CD45, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, CD19, CD16, CD56, CD11b, CD45RA, CD45RO, CD62L, and CD127 (Coulter); CD25 (conjugated to biotin, mouse immunoglobulin G2b, clone 4E3); glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor, cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated antigen 4, CD49d, and CD39 (Miltenyi Biotec); and FoxP3 (eBioscience). Mouse immunoglobulin G2-allophycocyanin (e-Bioscience) was used as a control for FoxP3 analysis. Dot plots of combined stainings with CD25/CD127/FoxP3 and CD25/CD45RA/FoxP3 were also performed on a different series of 3 donors. Cells were analyzed with a Cytomics FC500 Cytometer (Coulter). Release criteria were ≥ 90% CD4+/CD25+ and ≥ 50% FoxP3+ cells in the Treg product.

The suppressive capacity of the immunoselected population was established as follows. Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)–labeled CD4+/CD25− (Tcons) were in cultured in 96-well plates at 2 × 104 cells/well with phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 4 μg/mL; Biochrom) in the presence of varying amounts of CD4+/CD25+ (Tregs). For a CFSE-based measurement of proliferation, the suppressive capacity of Tregs toward responder cells in coculture (a Tcon:Treg ratio of 1:1 or 1:2) was expressed as the relative inhibition of the percentage of CFSElow cells as follows: 100 × (1 − %CFSElowCD4+CD25− T cells in coculture/%CFSElowCD4+CD25− T cells alone).

Chimerism analysis and immunologic studies

Chimerism was assessed on DNA extracted from peripheral blood samples by multiplex fluorescent short-tandem repeat analysis (AmpFISTR Profiler Plus PCR kit; Applied Biosystems). Peripheral blood was collected in EDTA for lymphocyte analysis weekly for the first 2 months and then monthly. Flow cytometric immunophenotyping analyzed lymphocyte subsets, including CD20+, CD8+CD16+CD56+, CD3+CD4+, CD3+CD8+, CD4+CD45RA+, CD4+CD45RO+, and CD8+CD45RA+, CD8+CD45RO+, CD4+CD25+. All antibodies were obtained from Coulter. Cells were analyzed using a Cytomics FC500 Cytometer (Coulter).

TCR third complementarity–determining region spectratyping

Spectratyping was performed on recipients' peripheral blood every 30 days after transplantation. The CDR3 size distribution of 26 T-cell receptor (TCR) Vβ families was determined by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as described previously.15 In brief, RNA was extracted and cDNA synthesized using Moloney murine leukemia virus–RT (Nanogen Advanced Diagnostic). PCR was performed with a specific forward primer for one of the TCR Vβ families, along with a constant Cβ reverse primer labeled with carboxyfluorescein.16 RT-PCR products were analyzed on an ABI PRISM 3130 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) using GeneScan software Gene Mapper Version 3.2. Normal TCR Vβ CDR3 was characterized by a Gaussian distribution containing 8-10 peaks for each Vβ subfamily. The overall complexity of TCR Vβ subfamilies was determined by spectratype scoring, as described previously.17

Limiting dilution assay to evaluate pathogen-specific responses in CD4+ T cells

Patient PBMCs to be used as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) were irradiated with 20 Gy and plated in 96 U-bottomed plates at the concentration of 2 × 106/mL (2 × 105 cells/well), in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% donor plasma and pulsed with cytomegalovirus (CMV), Aspergillus fumigatus conidia, Candida albicans yeasts, Toxoplasma gondii, herpes simplex virus (HSV), adenovirus (ADV), and varicella zoster virus (VZV) antigens.18 Patient cells (the selection criteria were a percentage of CD3+ cells equal to 5%-10% of the peripheral blood leukocytes) to be used as responder cells were plated on irradiated, antigen-pulsed cells at concentrations ranging from 10 000 to 125 cells/well for CMV-, C albicans–, T gondii–, HSV-, ADV-, and VZV-specific responses, and from 100 000 to 3500 for A fumigatus–specific responses. CMV, T gondii, HSV, and ADV antigens were from Microbix Biosystems as full proteins inactivated using γ radiation. As VZV antigens, we used the commercial vaccine (Varivax; Sanofi Pasteur). Heat-inactivated A fumigatus conidia and C albicans yeasts were provided by the Microbiology Division, University of Perugia. On day +14 of culture, interleukin-2 (IL-2) was added at the final concentration of 100 IU/mL. On days 14-18, wells containing growing clones were counted by screening plates with an inverted microscope. Clones were assessed for the CD3, CD4, CD8, αβ, and γδ TCR phenotype, as described.18 After resting in IL-2–free medium for 24 hours, pathogen specificity was assessed by restimulating clones with pathogen-pulsed irradiated APCs for 3 days. DNA synthesis was measured by H3-thymidine uptake, as described. To consider thymidine incorporation of a clone that is Ag reactive as Ag specific, the counts per million should be between the value of the clone stimulated with autologous APCs alone and the value of the clone stimulated with PHA.

Limiting dilution assay to evaluate pathogen-specific responses in CD8+ T cells

Patient PBMCs to be used as APCs were irradiated with 20 Gy and plated in 96 U-bottomed plates at a concentration of 2 × 106/mL (2 × 105 cells/well) in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% donor plasma, and pulsed with CMV, T gondii, HSV, ADV, and VZV.18 Patient CD8+ cells were separated by negative selection using anti-CD4 and anti-CD16 immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). Patient CD8+ cells to be used as responder cells were plated on irradiated, antigen-pulsed cells at concentrations ranging from 40 000 to 1250 cells/well. On day +1 of culture, IL-2 was added to a final concentration of 0.5 IU/mL. On days +10 and +14, IL-2 concentrations were raised to, respectively, 1.0 and 20.0 IU/mL. Between days +18 and +21, wells containing growing clones were counted by screening plates with an inverted microscope. Clones were assessed for the CD3, CD4, CD8, αβ, and γδ TCR phenotype, as described.18 Thymidine incorporation for CD8+ cells was calculated as described for CD4+ cells.

KIR phenotyping and NK-cell functional analysis

The alloreactive natural killer (NK)–cell subsets in donors and monthly in recipients after transplantations were phenotyped using different combinations of GL-183 (anti-KIR2DL2/L3/S2), EB6B (anti-KIR2DL1/S1), and Z27 (anti-KIR3DL1/S1) mAbs conjugated with fluorochrome phycoerythrin #143211 (anti-KIR2DL1), DX9 (anti-KIR3DL1), and Z199 (anti-NKG2A) mAbs conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate. Samples were analyzed by cytofluorometry on a FACSCanto using the Diva program (Becton Dickinson). Functional analysis of alloreactive NK-cell subsets in donors and monthly in recipients after transplantation were assessed in cytotoxicity assays against recipient target cells and/or killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) ligand mismatched vs the donor, to determine the frequency of alloreactive NK clones. PBMCs depleted of T cells by negative anti-CD3 immunomagnetic selection (Miltenyi Biotec) were plated under limiting-dilution conditions, activated with PHA (Biochrom), and cultured with IL-2 (Chiron) and irradiated feeder cells. Cloning efficiencies ranged from 1 in 5 to 1 in 10 plated NK cells. Cloned NK cells were screened for alloreactivity by standard 51Cr-release cytotoxicity at an effector-to-target ratio of 10:1 against allogeneic, KIR ligand–mismatched PHA lymphoblasts. Clones exhibiting greater than 30% lysis were scored as alloreactive.

Results

Treg and Tcon characteristics

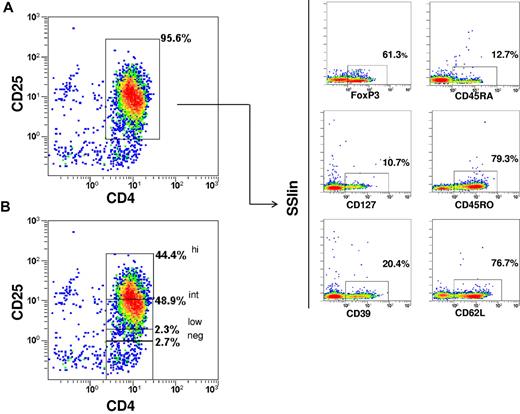

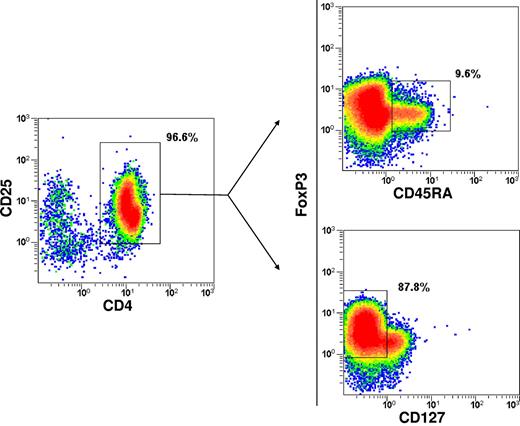

The phenotype of the immunoselected CD4+/CD25+ Tregs (purity 92.7% ± 2.1) was CD25high 33.6% ± 13.1; CD25int 52.6% ± 8.9; CD25low 4.7% ± 2.7; FoxP3 69.2% ± 13.9; CD127 16.6% ± 6.8 (mean ± SD). CD45RO+ cells were predominant, whereas the CD45RA+ cells accounted for only approximately 10%. CD62L and CD39 expression was enriched (Figure 2). Dot plots of combined stainings with CD25/CD45RA/FoxP3 and CD25/CD127/FoxP3 showed that 3.7% ± 4.1 of cells were FoxP3+/CD45RA+ and 94.3% ± 4.4 were FoxP3+/CD127− (Figure 3). The in vitro suppressive capacity was 67% ± 22 (mean ± SD; ratio of Tcons:Tregs, 1:2).

Immunophenotype of the immunoselected Tregs. The phenotype belongs to one representative case. (A) CD4/CD25 purity. (B) CD25 expression within final fraction. FoxP3, CD127, CD45RO, CD45RA, CD39, and CD62L expressions are also shown.

Immunophenotype of the immunoselected Tregs. The phenotype belongs to one representative case. (A) CD4/CD25 purity. (B) CD25 expression within final fraction. FoxP3, CD127, CD45RO, CD45RA, CD39, and CD62L expressions are also shown.

Immunophenotype of the immunoselected Tregs. Dot plots of combined stainings with CD25/CD45RA/FoxP3 and CD25/CD127/FoxP3 are shown. Positive cells are boxed and the percentage of cells is shown.

Immunophenotype of the immunoselected Tregs. Dot plots of combined stainings with CD25/CD45RA/FoxP3 and CD25/CD127/FoxP3 are shown. Positive cells are boxed and the percentage of cells is shown.

The Tcon composition was: CD3 93.16% ± 4.82; CD4 60.19% ± 7.24; CD8 32.22% ± 6.48; CD25 4.85% ± 2.17.

Engraftment and GVHD

Twenty-six of the 28 patients achieved primary, sustained full-donor–type engraftment. Neutrophils reached 1 × 109/L at a median of 15 days (range, 11-39). Platelets reached 25 × 109/L and 50 × 109/L medianly at 13 and 15 days, respectively (ranges, 11-48 and 13-60, respectively). Only 2 of 26 evaluable patients developed ≥ grade 2 acute GVHD, and both were among the 5 patients who had received 4 × 106/kg Tregs and 2 × 106/kg Tcons. At a median follow-up of 11.2 months (range, 3.6-21.4), no patient had developed chronic GVHD.

Posttransplantation immune recovery

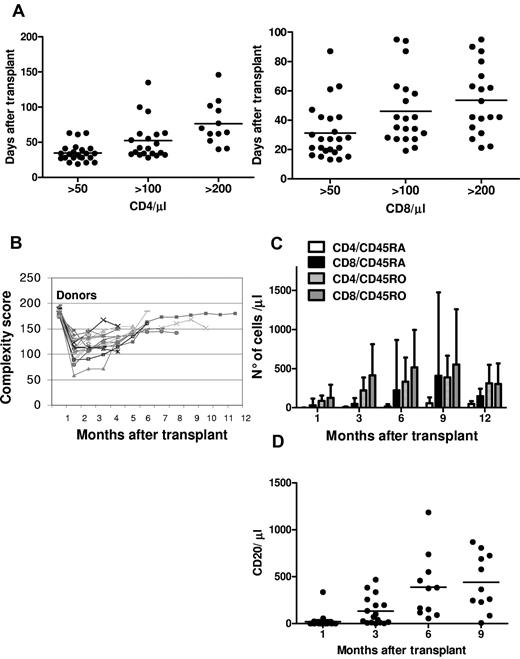

There was a rapid, sustained increase in peripheral blood T-cell subpopulations. CD4 and CD8 counts reached 50/μL medianly on, respectively, days 33 (range, 19-63) and 27 (range, 13-87); 100/μL medianly on days 42 (range, 28-135) and 38 (range, 19-95); and 200/μL on days 67 (range, 40-146) and 48 (range, 21-95; Figure 4A). A wide T-cell repertoire developed rapidly (Figure 4B). Naive and memory T-cell subsets increased significantly over the first year after transplantation, demonstrating sustained immune recovery over time (Figure 4C). B-cell reconstitution was rapid and sustained. CD20+ cells reached a mean of 132/μL 3 months after transplantation (Figure 4D). Immunoglobulin serum levels normalized within 3 months.

Immunologic reconstitution after Treg-based transplantation. (A) CD4 (left) and CD8 (right) recovery kinetics. (B) Posttransplantation TCR Vβ spectratyping complexity score over time. (C) Naive and memory T-cell recovery. (D) CD20+ recovery kinetic.

Immunologic reconstitution after Treg-based transplantation. (A) CD4 (left) and CD8 (right) recovery kinetics. (B) Posttransplantation TCR Vβ spectratyping complexity score over time. (C) Naive and memory T-cell recovery. (D) CD20+ recovery kinetic.

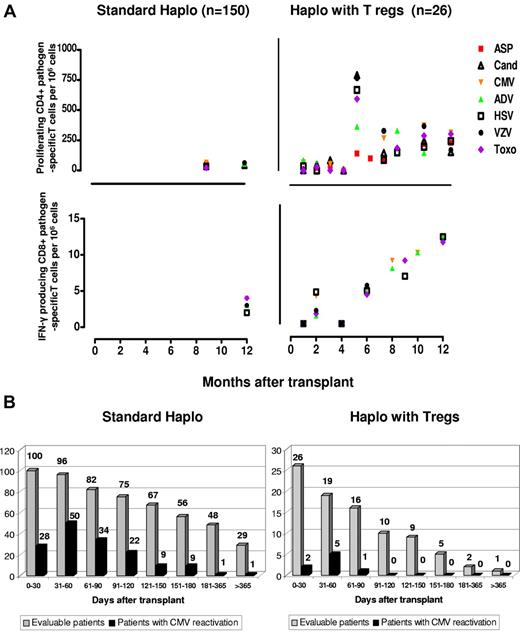

Compared with standard haploidentical transplantation, specific CD4+ and CD8+ for opportunistic pathogens such as A fumigatus, C albicans, CMV, ADV, HSV, and VZV toxoplasma emerged significantly earlier (at each time point P < .0001) (Figure 5A), fewer episodes of CMV reactivation occurred (Figure 5B), and no patient developed CMV disease. CMV clearance was often associated with expansion of specific CD8 cells. Treg counts were monitored at different time points for more than 1 year. Only a median of 7.5 (range, 1-19) CD4/CD25high cells/μL was found in the peripheral blood after 6 months posttransplantation and a median of 11 (range, 5-14) CD4/CD25high cells/μL was found after 1 year.

Immunologic reconstitution after Treg-based transplantation. (A) Reconstitution of pathogen-specific T-cell responses. Right panels: posttransplantation frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ pathogen-specific T-cell clones in Treg-haploidentical transplantation versus standard haploidentical transplantation (left panels). Sample numbers were at least 3 for each time point. CD4+ pathogen-specific T-cell clones in the Treg haploidentical transplantation group at month +1 (ASP = 2.6 ± 1.2; CAND = 5.3 ± 2.1; CMV = 115 ± 61; ADV = 156 ± 78; HSV = 32 ± 4; TOXO = 65 ± 26; VZV = 48 ± 34); at months +3 (ASP = 37.5 ± 34; CAND = 69.5 ± 42; CMV = 68 ± 48; ADV = 422 ± 333; HSV = 79 ± 16; TOXO = 170 ± 57; VZV = 48 ± 34); at months +6 (ASP = 91.6 ± 29; CAND = 133 ± 91; CMV = 259 ± 245; ADV = 303 ± 216; HSV = 137 ± 90; TOXO = 263 ± 156; VZV = 337 ± 280); at months +12 (ASP = 210.5 ± 190.2; CAND = 139 ± 104; CMV = 359 ± 288; ADV = 160 ± 103; HSV = 222 ± 173; TOXO = 277 ± 218; VZV = 155 ± 111) (P < .0001 compared with standard haploidentical transplantations at each time point). CD8+ pathogen-specific T-cell clones in the Treg-haploidentical transplantation group at month +1 (CMV = 1.2 ± 3; ADV = 0; HSV = 1.5 ± 1; TOXO = 3 ± 0.4; VZV = 2 ± 2); at month +3 (CMV = 4.4 ± 3.5; ADV = 0; HSV = 1.6 ± 1.5; TOXO = 1.5 ± 1.2; VZV = 4.2 ± 4); at month +6 (CMV = 4.3 ± 2.3; ADV = 4 ± 3.4; HSV = 4.8 ± 4.5; TOXO = 3.6 ± 2; VZV = 4.2 ± 4.1); at month +12 (CMV = 11 ± 1; ADV = 11 ± 1; HSV = 9 ± 2; TOXO = 10.3 ± 1.5; VZV = 11 ± 1) (P < .0001 compared with standard haploidentical transplantations at each time point). (B) Episodes of CMV reactivation are significantly lower (P < .05) after “haplo with Tregs” (right panel) compared with “standard haplo” (left panel) transplantations.

Immunologic reconstitution after Treg-based transplantation. (A) Reconstitution of pathogen-specific T-cell responses. Right panels: posttransplantation frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ pathogen-specific T-cell clones in Treg-haploidentical transplantation versus standard haploidentical transplantation (left panels). Sample numbers were at least 3 for each time point. CD4+ pathogen-specific T-cell clones in the Treg haploidentical transplantation group at month +1 (ASP = 2.6 ± 1.2; CAND = 5.3 ± 2.1; CMV = 115 ± 61; ADV = 156 ± 78; HSV = 32 ± 4; TOXO = 65 ± 26; VZV = 48 ± 34); at months +3 (ASP = 37.5 ± 34; CAND = 69.5 ± 42; CMV = 68 ± 48; ADV = 422 ± 333; HSV = 79 ± 16; TOXO = 170 ± 57; VZV = 48 ± 34); at months +6 (ASP = 91.6 ± 29; CAND = 133 ± 91; CMV = 259 ± 245; ADV = 303 ± 216; HSV = 137 ± 90; TOXO = 263 ± 156; VZV = 337 ± 280); at months +12 (ASP = 210.5 ± 190.2; CAND = 139 ± 104; CMV = 359 ± 288; ADV = 160 ± 103; HSV = 222 ± 173; TOXO = 277 ± 218; VZV = 155 ± 111) (P < .0001 compared with standard haploidentical transplantations at each time point). CD8+ pathogen-specific T-cell clones in the Treg-haploidentical transplantation group at month +1 (CMV = 1.2 ± 3; ADV = 0; HSV = 1.5 ± 1; TOXO = 3 ± 0.4; VZV = 2 ± 2); at month +3 (CMV = 4.4 ± 3.5; ADV = 0; HSV = 1.6 ± 1.5; TOXO = 1.5 ± 1.2; VZV = 4.2 ± 4); at month +6 (CMV = 4.3 ± 2.3; ADV = 4 ± 3.4; HSV = 4.8 ± 4.5; TOXO = 3.6 ± 2; VZV = 4.2 ± 4.1); at month +12 (CMV = 11 ± 1; ADV = 11 ± 1; HSV = 9 ± 2; TOXO = 10.3 ± 1.5; VZV = 11 ± 1) (P < .0001 compared with standard haploidentical transplantations at each time point). (B) Episodes of CMV reactivation are significantly lower (P < .05) after “haplo with Tregs” (right panel) compared with “standard haplo” (left panel) transplantations.

To further investigate immune competence, 7 patients (3-14 months after stem cell transplantation) were vaccinated against pandemic influenza with 2 doses of MF59-H1N1california. Five of 7 patients achieved protective antibody titers (≥ 40 in hemoagglutinin inhibition and microneutralization) and marked increases in H1N1 california–specific CD4+ T cells.

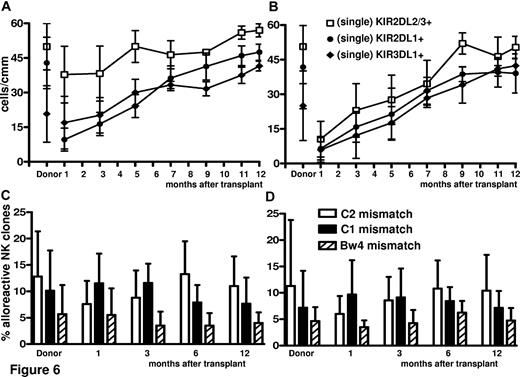

Adoptive immunotherapy with Tregs did not impair NK-cell reconstitution/maturation (Figure 6), which was faster with enhanced donor-alloreactive NK-cell repertoires against KIR-ligand–mismatched targets. In particular, NK cells expressing single KIR responsible for NK-cell alloreactivity were higher and reconstituted faster (KIR2DL2/3 P < .01 at 1, 3, and 5 months) in Treg-haploidentical transplantation than in standard haploidentical transplantations (Figure 6A vs 6B). The frequency of alloreactive NK clones directed against KIR-ligand–mismatched recipient target cells was also higher (P = NS) (Figure 6C vs 6D).

Regeneration of alloreactive NK-cell repertoires against a KIR-ligand–mismatched target. (A-B) Immunophenotype of NK-cell repertoire in donors and recipients after Treg (A) and standard (B) HLA-haploidentical transplantation identified potentially alloreactive NK cells expressing single KIR. KIR2DL2/3 P < .01 at 1, 3, and 5 months. (C-D) Cytotoxicity assay identified alloreactive NK cells that killed KIR ligand–mismatched PHA lymphoblasts in donors and recipients after Treg (C) and standard (D) HLA-haploidentical transplantation (P = NS).

Regeneration of alloreactive NK-cell repertoires against a KIR-ligand–mismatched target. (A-B) Immunophenotype of NK-cell repertoire in donors and recipients after Treg (A) and standard (B) HLA-haploidentical transplantation identified potentially alloreactive NK cells expressing single KIR. KIR2DL2/3 P < .01 at 1, 3, and 5 months. (C-D) Cytotoxicity assay identified alloreactive NK cells that killed KIR ligand–mismatched PHA lymphoblasts in donors and recipients after Treg (C) and standard (D) HLA-haploidentical transplantation (P = NS).

Outcomes

Thirteen of 26 patients died due to venoocclusive disease,3 multiorgan failure,1 adenoviral infection,1 adenoviral infection and GVHD,1 GVHD,1 bacterial sepsis,1 systemic toxoplasmosis,1 fungal pneumonia,3 or central nervous system aspergillosis.1 One AML patient who had been transplanted in chemoresistant relapse from a non–NK-alloreactive donor relapsed 6 months after transplantation. At a median follow-up of 12 months (range, 9-21), 12 of 26 (46.1%) patients were alive and disease free.

Discussion

In HLA-haploidentical transplantation without posttransplantation immunosuppression, extensive ex vivo T-cell depletion (3.5-4 × log10 ) of the graft is mandatory to prevent acute and chronic GVHD. In children with combined immunodeficiency who receive HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation, 4 × 104 T cells/kg has been identified as the GVHD threshold dose.19 In adults with acute leukemia, after a conditioning regimen that included total body irradiation, cyclophosphamide, thiotepa, and ATG, 1-5 × 105/kg T cells contaminating the CD34+ cell inoculum were associated with an 18% incidence of grades II-IV GVHD.5 To reduce the incidence of GVHD, the number of T lymphocytes in the graft was lowered to one-tenth (1-3.5 × 104 T cells/kg). Acute GVHD developed in 8 of 141 evaluable patients (< 5%).1,2

In assessing the real threshold dose, the effects of anti–T-lymphocyte antibodies in the conditioning regimens need to be factored in. ATG, with its 6-day plasma half-life, may exert an in vivo cytotoxic effect against donor T lymphocytes and thus help to prevent GVHD. Similar considerations can be applied to OKT3, which has been used in children.20 Interestingly, adding back 3 × 104/kg donor T lymphocytes to improve posttransplantation immune reconstitution 2-3 months after transplantation, which is beyond the time frame of the ATG half-life, was associated with a high risk of severe GVHD.1,2

The present study demonstrates for the first time that adoptive immunotherapy with freshly purified CD4+CD25+ Tregs counteracts the GVHD potential of a high number of donor Tcons in HLA-haploidentical HSCT. The striking finding was the absence of GVHD in patients who received up to 1 × 106 Tcons/kg (2 logs more than in the above-mentioned studies) after an infusion of 2 × 106 Tregs. It is worth noting that no posttransplantation immunosuppression was given and, because the conditioning regimen contained cyclophosphamide instead of ATG, there was no ATG-related lympholytic action on effector T cells. When 2 × 106/kg Tcons were infused, 2 of 5 patients developed GVHD. Therefore, we can conclude that 1 × 106/kg Tcons is the GVHD threshold dose in this type of HLA-haploidentical transplantation setting. We may, however, hypothesize that the real number of infused Tcons was even greater, because the immune-selected CD4+CD25+ cells contained approximately 30% FoxP3− cells, which are potentially effector T cells. Conversely, the number of Tregs might also have been greater in vivo, because they could have proliferated in the postconditioning proinflammatory environment of the T cell–depleted host in the 4-day interval before the Tcons were infused. In fact, preclinical studies have demonstrated that in vivo Treg activation and expansion permits the subsequent infusion of more Tcons without triggering GVHD.14

One issue to be investigated in future studies is whether adoptive immunotherapy with Tregs compromises general immunity, blunting responses to infectious agents. In animal models, the infusion of recipient-type specific Tregs12 and polyclonal purified Tregs and Tcons10 promoted immune reconstitution and protected mice from lethal CMV infection.10 In our clinical setting, naturally occurring, polyclonal purified Tregs did not inhibit the expansion of coinfused Tcons with a broad TCR repertoire. CD4+ and CD8+ cell counts achieved sustained levels quickly, unlike standard T cell–depleted mismatched HSCT with CD4+ cell counts below 100 and 200/μL for 10 and 16 months, respectively.1 High frequencies of pathogen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell precursors were detected as early as 2 months, rather than 9-12 months, after transplantation.18 Strikingly, the prevention of CMV disease was markedly improved, with no CMV-related deaths. CMV had been the major cause of mortality, accounting for 40% of nonleukemic deaths, in our previous study.2 We may hypothesize that, as in animal models, in a postconditioning inflammatory environment, Tregs are activated by recipient APCs, block alloreactive T cells in an antigen-specific fashion, and allow the expansion of nonalloreactive T cells, which ensures long-term immunity.

In adults with high-risk acute leukemias, HSCT from alternative sources (matched unrelated donor, unrelated cord blood, and full-haplotype–mismatched family member) are still associated with quite high transplantation-related mortality.2,21,22 In our previous studies of full-haplotype mismatched HSCTs, mortality from causes other than leukemia relapse was 40%1 and 36.5%.2 In the present study, the 50% transplantation-related mortality needs to be viewed in light of these outcomes and of the clinical characteristics of this cohort. Four of the 13 deaths were due to regimen-related toxicity, and 3 of these patients had been heavily pretreated with several lines of polychemotherapy including gemtuzumab ozogamicin. The 4 patients who died of aspergillosis had fungal localization in the lungs (3 patients) and central nervous system (1 patient) before transplantation. No fatal infections occurred after the first 2 months posttransplantation, confirming the good recovery of immune response against pathogens.

Another crucial point about adoptive immunotherapy with Tregs is whether the graft-vs-leukemia effect is maintained, as has been reported in some animal models.12,23 Surprisingly, in patients at very high risk of relapse, only 1 relapse has occurred at a median follow-up of 12 months in a patient with AML who was transplanted in chemoresistant relapse from a non–NK-alloreactive donor. Although no definitive conclusions can be drawn, the low incidence of relapse may have been due to the powerful regeneration of donor-vs-recipient alloreactive NK repertoires in patients who received a transplantation from a potentially NK-alloreactive donor.24 Moreover, in all patients, the high number of infused Tcons are hypothesized to exert a graft-versus-leukemia effect by recognizing leukemia-associated antigens. In any case, the Treg infusion is clearly not associated with increased incidence of leukemia relapse.

In conclusion, combining donor Tregs and Tcons in this first clinical trial prevented GVHD and enhanced immune recovery, providing evidence that Treg properties are a conserved mechanism in humans.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Geraldine Anne Boyd for her help.

This work was supported by Azienda Ospedaliera di Perugia, Progetto Oncologico Regione Umbra, “Associazione Umbra Leucemie e Linfomi,” Perugia, and by “Associazione Italiana Leucemie, Linfomi e Mieloma,” L'Aquila Section, Italy.

Authorship

Contribution: M.D.I., F.F., and M.F.M. designed the study and oversaw the results; M.D.I. and M.F.M. drafted the paper; B.F., Y.R., A.V., and F.A. contributed to the design and interpretation of the study; A.C., A.T., T.A., A.P., P.S., and C.A. provided clinical data; and F.C., E.B., B.D.P., T.Z., R.I.O., D.C., K.P., L.R., and C.B performed the in vitro studies and interpreted the results.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mauro Di Ianni, Chair of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine and Public Health, University of L'Aquila, 67100 L'Aquila, Italy; e-mail: mauro.diianni@cc.univaq.it.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal