Abstract

We analyzed prevalence, characteristics, clinical correlates, and prognostic significance of autoimmune cytopenia in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Seventy of 960 unselected patients (7%) had autoimmune cytopenia, of whom 19 were detected at diagnosis, 3 before diagnosis, and 48 during the course of the disease. Forty-nine patients had autoimmune hemolytic anemia, 20 had immune thrombocytopenic purpura, and 1 had both conditions. A clear association was observed between autoimmune cytopenia and poor prognostic variables (ie, high blood lymphocyte count, rapid blood lymphocyte doubling time, increased serum β-2 microglobulin level, and high expression of ζ-associated protein 70 and CD38). Nevertheless, the outcome of patients with autoimmune cytopenia as a whole was not significantly different from that of patients without this complication. Furthermore, no differences were observed according to time at which cytopenia was detected (ie, at diagnosis, during course of disease). Importantly, patients with advanced (Binet stage C) disease because of an autoimmune mechanism had a significantly better survival than patients in advanced stage related to a massive bone marrow infiltration (median survivals: 7.4 years vs 3.7 years; P = .02). These results emphasize the importance of determining the origin of cytopenia in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia for both treatment and prognostic purposes.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is characterized by the progressive accumulation of B cells with mature appearance and a distinctive immunophenotype (ie, SmIgdim, CD5+ CD19+, CD20dim, CD23+) in peripheral blood, bone marrow, lymph nodes, and other lymphoid tissues.1,2 In addition, CLL is frequently associated with autoimmune phenomena, particularly autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA).3 Thus, between 5% and 25% of patients with CLL develop AIHA, whereas immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is less frequent with an estimated 1%-5% in most recent studies.4-7

Prognosis of patients with CLL is extremely variable. Despite the increasing importance of biomarkers in prognostication, clinical staging systems remain the backbone for assessing prognosis in patients with CLL. Of note, neither Rai et al8 nor Binet et al9 staging systems consider the origin of cytopenia when assigning a clinical stage to a given patient. However, to ascertain the outcome of patients with CLL in advanced clinical stage on the basis of the origin of the cytopenia (ie, “immune” vs “infiltrative”) can be important because of prognostic and treatment considerations.10

Although remarkable advances have been made in our understanding of the pathophysiology of CLL, little is known about the causes and clinical implications of autoimmune cytopenia in patients with this form of leukemia. Furthermore, the effect of autoimmune cytopenias on the clinical outcome of patients with CLL remains controversial.4,5,7,11 In this regard, there are few reports that analyzed the prevalence, clinical correlates, prognostic factors, and outcome of autoimmune cytopenia in large, unselected series of patients with CLL from single institutions.4,5

The aims of this study were 3-fold. First, we wanted to determine the prevalence of autoimmune cytopenia in a large series of unselected patients with CLL. Second, we sought to correlate autoimmune cytopenia with clinical and biologic features. Third, we wished to ascertain the prognosis of autoimmune cytopenia in CLL, particularly in patients with advanced clinical stage (Binet stage C).

Methods

Patients

The study population comprises 960 patients with CLL diagnosed at the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona between January 1980 and December 2008. Patients with a diagnosis of autoimmune cytopenia were identified from this database, and their case records were reviewed. Demographic as well as characteristics at diagnosis and prognostic factors, including blood lymphocyte count and lymphocyte doubling time (LDT), percentage of lymphocytes in bone marrow, β-2 microglobulin (B2M) serum levels, cytogenetic abnormalities, IGHV mutation status, ζ-associated protein 70 (ZAP-70), and CD38 expression, were registered, and their association with immune cytopenias was analyzed. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona.

Diagnostic criteria

The diagnosis of CLL was made according to criteria from the National Cancer Institute,12,13 and whenever possible the diagnosis was confirmed by flow cytometry. The diagnosis of AIHA was based on the presence of an otherwise unexplained hemoglobin level < 100 g/L (< 10 g/dL) or hematocrit < 30% and a positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT) for either immunoglobulin G or C3 and the presence of ≥ 1 indirect marker of hemolysis: high reticulocyte count, low serum haptoglobin levels, increased serum lactate dehydrogenase or bilirubin levels. For patients in whom DAT was negative, the diagnosis of AIHA was made if ≥ 2 of the indirect signs of hemolysis were present.5 ITP was defined as a sudden and otherwise unexplained fall in platelet count to < 100 × 109/L (< 100 000/mm3) with ≥ 2 of the following: evidence of normal bone marrow function (normal or increased megakaryocytes in bone marrow, or no reticulocytopenia if bone marrow aspirate was not available), no splenomegaly, no chemotherapy within the last month from study entry.7 Patients were confirmed as having stage C “infiltrative” if they had either hemoglobin level < 100 g/L (< 10 g/dL) or platelet count < 100 × 109/L (< 100 000/mm3) with no positive DAT and no indirect signs of hemolysis, and further confirmed whenever possible by a significant marrow infiltration as defined by either a diffuse bone marrow histologic pattern or, when this was not available, by the less accurate bone marrow aspirate (> 80% lymphocytes) or reticulocytopenia (< 1%).

Study design and statistical end points

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared with the chi-square and Mann-Whitney tests for categorical and ordinal samples, respectively.14 Patients in whom the diagnosis of CLL and that of autoimmune cytopenia was made within a month of each other were considered to have C “immune” stage at diagnosis. Survival analyses were performed according to the Kaplan-Meier method and analyzed by the log-rank test.14 Overall survival was defined as the time interval from the diagnosis of CLL to death from any cause or last follow-up. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc) and Stata 10 software (www.stata.com), and a P value of ≤ .05 was considered significant. Different treatment protocols used over this period of time were approved by the ethics committee of our institution. Briefly, 419 of 960 patients received treatment for their CLL. Fifty-five percent of the patients (231 of 419) were given chlorambucil-based regimens, and 49% of the patients (204 of 419) were given fludarabine-containing regimens at some point during their follow-up; among the latter, 64 patients received fludarabine alone and 140 received fludarabine-containing regimens.

Most patients with autoimmune cytopenia were initially treated with corticosteroids. Details of treatment modalities and response to therapy are shown in Table 1.

Treatment and response to therapy of autoimmune cytopenia in patients with CLL

| Treatment . | AIHA DAT+ (n = 43)* . | AIHA DAT− (n = 7) . | ITP (n = 20) . | All (n = 70) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroid-based therapy (n = 58) | ||||

| Steroids alone | 16 | 5 | 9 | 30 |

| Steroids + other† | 20 | 1 | 7 | 28 |

| Chemotherapy‡ | 6 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Other§ | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Outcome | ||||

| Single resolved episode | 19 | 2 | 10 | 31 |

| > 1 episode | 8 | 1 | 8 | 17 |

| Steroid dependent | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Died with active immune disease‖ | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Unknown | 7 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| Treatment . | AIHA DAT+ (n = 43)* . | AIHA DAT− (n = 7) . | ITP (n = 20) . | All (n = 70) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroid-based therapy (n = 58) | ||||

| Steroids alone | 16 | 5 | 9 | 30 |

| Steroids + other† | 20 | 1 | 7 | 28 |

| Chemotherapy‡ | 6 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Other§ | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Outcome | ||||

| Single resolved episode | 19 | 2 | 10 | 31 |

| > 1 episode | 8 | 1 | 8 | 17 |

| Steroid dependent | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Died with active immune disease‖ | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Unknown | 7 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

CLL indicates chronic lymphocytic leukemia; AIHA, autoimmune hemolytic anemia; DAT, direct antiglobulin test; and ITP, immune thrombocytopenic purpura.

One patient presented with both AIHA DAT+ and ITP.

Refers to patients who in addition to steroids received other treatments: cyclophosphamide (n = 19), splenectomy (n = 6), rituximab (n = 3), intravenous immunoglobulin (n = 3), vincristine (n = 3), azathioprine (n = 1).

Chemotherapy regimens were chlorambucil (n = 4); cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovin, prednisone (CHOP; n = 2); CHOP + BCNU (bis-chloroethyl-nitroso-urea), etoposide, cytosine arabinoside, melphalan + autologous stem cell transplantation (n = 1).

Spontaneous resolution (n = 2), Helicobacter pylori eradication (n = 1).

In no case could death be attributed to autoimmune cytopenia solely.

Results

CLL population and prevalence of autoimmune cytopenia

Over the 28-year study period the diagnosis of autoimmune cytopenia was entertained in 93 of 961. However, on review, 23 patients were excluded from the study because they failed to fulfill the strict diagnostic criteria described in “Methods.” As a result, the diagnosis of autoimmune cytopenia was confirmed in 70 patients, thus giving a prevalence of 7%. Forty-nine patients had AIHA (42 DAT+, 7 DAT−), 20 had ITP, and 1 patient presented with both AIHA and ITP (Evans syndrome). Three of the patients who initially had ITP later developed AIHA. The presentation of autoimmune cytopenia was 1 year before the diagnosis of CLL in 3 patients (1 AIHA, 2 ITP), at the time of diagnosis in 19 patients (12 AIHA, 7 ITP), and in 48 patients it appeared during the evolution of the disease (36 AIHA, 11 ITP, 1 Evans syndrome).

Thirty-five of 70 patients developed either ITP or AIHA during (n = 11) or after (n = 24) therapy with a median time of 6 months (range, 0-120 months) since treatment exposure. Eight patients had received fludarabine-containing regimens (1 fludarabine alone and 7 fludarabine in combination with cyclophosphamide and mitoxantrone) and 18 received chlorambucil. Thus, the prevalence of autoimmune cytopenia after fludarabine and chlorambucil regimens was 8 of 204 patients (4%) and 12 of 231 patients (5%), respectively (P = NS).

Clinical and biologic characteristics in patients with and without autoimmune cytopenia

The main clinical and biologic characteristics of patients with and without autoimmune cytopenia are listed in Table 2. Clinical characteristics associated with autoimmune cytopenia were a high lymphocyte count, short LDT, and advanced clinical stage. Furthermore, although not significantly different, there was a trend for a higher bone marrow infiltration in patients who developed autoimmune cytopenia.

Clinical and biological characteristics at diagnosis in patients who presented with autoimmune cytopenia versus patients without autoimmune cytopenia

| . | With autoimmune cytopenia (n = 70) . | Without autoimmune cytopenia (n = 867) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 65.5 (33-89) | 66 (24-97) | NS |

| Male (%) | 63 | 57 | NS |

| WBC count, ×109/L (range) | 28.3 (4.8-461) | 20.4 (2.5-454) | NS |

| Hb level, ×109/L (range) | 12.7 (4.6-18.10) | 13.8 (5-18.5) | < .05* |

| Platelet count, ×109/L (range) | 155 (10-347) | 188 (10-483) | < .05* |

| ALC, ×109/L (range) | 20.4 (2.8-410) | 14.2 (0.95-445) | .004 |

| BM infiltration, % (range)† | 60 (15-99) | 53 (3-100) | .075 |

| Binet stage, n (%) | |||

| A | 37 (53) | 671 (79) | |

| B | 9 (13) | 131 (15) | < .05* |

| C | 24 (34) | 54 (6) | |

| PS < 2, n (%) | 64 (92) | 824 (95) | NS |

| B2M > 2.5 mg/L, n/N (%) | 24/44 (55) | 185/502 (37) | .02 |

| LDT < 12 mo, n/N (%) | 17/46 (37) | 107/515 (21) | .01 |

| ZAP-70 > 20%, n/N (%) | 18/35 (51) | 142/432 (33) | .02 |

| CD38 > 30%, n/N (%) | 16/33 (48) | 129/393 (33) | .07 |

| Unmutated IGHV, n/N (%) | 11/22 (50) | 67/131 (51) | NS |

| Poor risk cytogenetics, n/N (%)‡ | 3/24 (13) | 44/254 (17) | NS |

| Follow-up, y (range) | 6.5 (0-25) | 5.5 (0-25) | NS |

| . | With autoimmune cytopenia (n = 70) . | Without autoimmune cytopenia (n = 867) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 65.5 (33-89) | 66 (24-97) | NS |

| Male (%) | 63 | 57 | NS |

| WBC count, ×109/L (range) | 28.3 (4.8-461) | 20.4 (2.5-454) | NS |

| Hb level, ×109/L (range) | 12.7 (4.6-18.10) | 13.8 (5-18.5) | < .05* |

| Platelet count, ×109/L (range) | 155 (10-347) | 188 (10-483) | < .05* |

| ALC, ×109/L (range) | 20.4 (2.8-410) | 14.2 (0.95-445) | .004 |

| BM infiltration, % (range)† | 60 (15-99) | 53 (3-100) | .075 |

| Binet stage, n (%) | |||

| A | 37 (53) | 671 (79) | |

| B | 9 (13) | 131 (15) | < .05* |

| C | 24 (34) | 54 (6) | |

| PS < 2, n (%) | 64 (92) | 824 (95) | NS |

| B2M > 2.5 mg/L, n/N (%) | 24/44 (55) | 185/502 (37) | .02 |

| LDT < 12 mo, n/N (%) | 17/46 (37) | 107/515 (21) | .01 |

| ZAP-70 > 20%, n/N (%) | 18/35 (51) | 142/432 (33) | .02 |

| CD38 > 30%, n/N (%) | 16/33 (48) | 129/393 (33) | .07 |

| Unmutated IGHV, n/N (%) | 11/22 (50) | 67/131 (51) | NS |

| Poor risk cytogenetics, n/N (%)‡ | 3/24 (13) | 44/254 (17) | NS |

| Follow-up, y (range) | 6.5 (0-25) | 5.5 (0-25) | NS |

NS indicates not significant; WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; BM, bone marrow; PS, performance status; B2M, β-2 microglobulin; LDT, lymphocyte doubling time; and ZAP-70, ζ-associated protein 70.

Significant differences are due to immune cytopenias.

Assessed by BM aspirate or biopsy or both.

Poor cytogenetics include del 17p, del 11q, trisomy 12, and the presence of ≥ 2 cytogenetic abnormalities as determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization and conventional cytogenetics.

In patients whose condition was more recently diagnosed and in whom these parameters were available, high serum B2M levels (P = .02) and increased expressions of ZAP-70 (P = .02) and CD38 (P = .07) were significantly associated with autoimmunity. No correlation was observed between autoimmune cytopenia and IGHV mutational status or adverse cytogenetics; these variables however were only available in 16% and 30% of the patients, respectively.

Outcome of patients with and without autoimmune cytopenia

Forty-six of the 70 patients with autoimmune cytopenia (66%) have died (5 of them while having active autoimmune disease) and 24 are alive (14 AIHA, 10 ITP) at the last follow-up. Among patients without autoimmune cytopenia, 443 of 867 (51%) have died and 424 are alive.

No significant differences were observed in the overall survival between patients with and without autoimmune cytopenia, the median survival being, respectively, 8 years (95% CI, 7-9) and 9 years (95%CI, 8-10; P = NS). Furthermore, median survival was 7, 7.4, and 8 years for patients in whom the autoimmune cytopenia appeared before, at diagnosis, or during the course of the disease. Patients with Binet stage A at diagnosis who later developed autoimmune cytopenia had a median survival from diagnosis of 9 years (95% CI, 7-11 years) versus 10 years (95% CI, 9-11 years) in patients who did not present this complication (P = NS; supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Likewise, median survival was 8.5 years (95% CI, 8-9 years) in patients with B stage who developed an autoimmune cytopenia versus 5.5 years (95% CI, 4-7years) in patients who did not present this complication (P = NS; supplemental Figure 2).

Comparison between C immune and C infiltrative and restaging after initial therapy

Table 3 shows clinical characteristics of patients who presented with CLL in stage C on the basis of the origin of the cytopenia (ie, immune vs infiltrative). Demographics, clinical characteristics, and median follow-up were comparable in both groups except for the bone marrow infiltration and serum B2M levels that were significantly higher in patients with Binet stage C infiltrative compared with patients with Binet stage C immune.

Clinical characteristics in patients with advanced stage at diagnosis according to the type of cytopenia: C immune versus C infiltrative

| . | C immune (n = 19) . | C infiltrative (n = 54) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 69 (40-86) | 70 (28-90) | NS |

| Male (%) | 74 | 65 | NS |

| WBC count, ×109/L (range) | 25.9 (9.9-334) | 30.1 (2.5-454) | NS |

| Hb, ×109/L (range) | 10.5 (6-16.6) | 10 (5-15.4) | NS |

| Platelet count, ×109/L (range) | 132 (19-347) | 89.5 (10-483) | NS |

| ALC, ×109/L (range) | 15.3 (4.4-257) | 23 (1.4-444) | NS |

| BM infiltration, % (range)* | 54 (16-99) | 80 (20-100) | 04 |

| PS < 2% | 67 | 83 | NS |

| B2M > 2.5 mg/L, % | 50 | 85 | .03 |

| No. of nodal areas | NS | ||

| ≤ 2 LN areas, n | 14 | 40 | NS |

| > 2 LN areas, n | 5 | 12 | NS |

| Follow-up, y | NS | ||

| All patients, median (range) | 5 (0-13) | 3.5 (0-13) | NS |

| Alive patients, median (range) | 5.6 (0-12.8) | 4 (0-7.3) | NS |

| . | C immune (n = 19) . | C infiltrative (n = 54) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 69 (40-86) | 70 (28-90) | NS |

| Male (%) | 74 | 65 | NS |

| WBC count, ×109/L (range) | 25.9 (9.9-334) | 30.1 (2.5-454) | NS |

| Hb, ×109/L (range) | 10.5 (6-16.6) | 10 (5-15.4) | NS |

| Platelet count, ×109/L (range) | 132 (19-347) | 89.5 (10-483) | NS |

| ALC, ×109/L (range) | 15.3 (4.4-257) | 23 (1.4-444) | NS |

| BM infiltration, % (range)* | 54 (16-99) | 80 (20-100) | 04 |

| PS < 2% | 67 | 83 | NS |

| B2M > 2.5 mg/L, % | 50 | 85 | .03 |

| No. of nodal areas | NS | ||

| ≤ 2 LN areas, n | 14 | 40 | NS |

| > 2 LN areas, n | 5 | 12 | NS |

| Follow-up, y | NS | ||

| All patients, median (range) | 5 (0-13) | 3.5 (0-13) | NS |

| Alive patients, median (range) | 5.6 (0-12.8) | 4 (0-7.3) | NS |

NS indicates not significant; WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; BM, bone marrow; PS, performance status; LN, lymph node.

Assessed by BM aspirate or biopsy or both.

After initial therapy, significant differences were observed in the response rate according to the origin of the cytopenia. Whereas 16 of the 19 patients with stage C immune disease responded to corticosteroids and, as a result, switched from stage C to stage A, only 9 of 54 patients with stage C infiltrative had a similar response to chemotherapy (P < .001). Furthermore, within C immune patients, 9 of 12 with AIHA and 7 of 7 with ITP were downstaged to A disease. This difference, however, was not statistically significant.

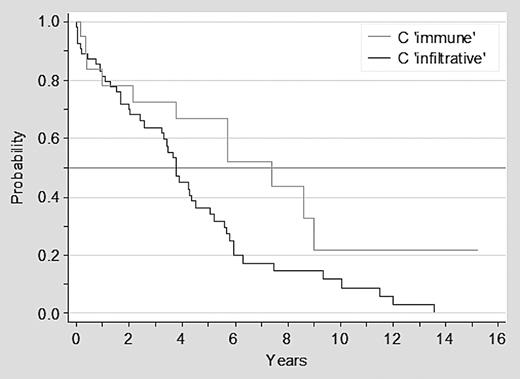

Survival analysis of patients with stage C immune versus stage C infiltrative at diagnosis

Overall 57 of 73 patients with advanced clinical stage at diagnosis have died: 46 of 54 (85%) of patients in stage C infiltrative and 11 of 19 (58%) with stage C immune. Patients with stage C immune disease had a significantly better survival than patients with stage C infiltrative disease, with a median survival of 7.4 versus 3.7 years, respectively (P = .02; Figure 1). Furthermore, there was a trend for a better outcome for patients with ITP than for patients with AIHA or stage C infiltrative disease (P = .06; Figure 2).

Survival of patients with CLL in advanced clinical stage C infiltrative versus C immune.

Survival of patients with CLL in advanced clinical stage C infiltrative versus C immune.

Survival of patients with CLL in advanced clinical stage C infiltrative versus AIHA versus ITP.

Survival of patients with CLL in advanced clinical stage C infiltrative versus AIHA versus ITP.

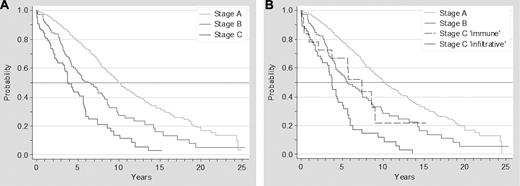

Survival according to clinical stages at diagnosis, including C immune as a prognostic category

The survival analysis of patients according to the Binet staging system showed the following median survivals: stage A, 10 years; stage B, 6.3 years; stage C, 3.9 years (P < .01). When stage C immune was included in the overall analysis as a distinct category, median survivals were as follows: stage A, 10.2 years; stage B, 5.6 years; stage C immune, 7.4 years; and stage C infiltrative, 3.7 years (P < .001; Figure 3).

Survival of patients with CLL according to Binet staging system. Survival of patients with CLL according to advanced Binet staging system (A) and to a modified Binet staging system, breaking down stage C according to the origins of cytopenia (infiltrative vs immune; B).

Survival of patients with CLL according to Binet staging system. Survival of patients with CLL according to advanced Binet staging system (A) and to a modified Binet staging system, breaking down stage C according to the origins of cytopenia (infiltrative vs immune; B).

Discussion

The association of CLL and autoimmune cytopenia was already recognized in seminal descriptions of the disease published in the late 1960s.15-17 The occurrence of AIHA or ITP has been reported to range from < 5% to 38%, depending on patient selection, length of follow-up, and definition of autoimmune cytopenia.3,6 In the present analysis, using strict diagnostic criteria, 70 of 960 patients with CLL were found to have AIHA or ITP at some point during the course of their disease. This results in a prevalence of 7%, which is in agreement with recent studies in which the percentage of patients with CLL and autoimmune cytopenia ranges from 4.5% to 10%.4,5,7 Note that for ITP, besides difficulties in diagnostic criteria, only acute onset, symptomatic ITP is usually recognized; therefore, the frequency of this complication might be underestimated.

The mechanisms underlying immune cytopenia in CLL are unclear, but red blood cell autoantibodies and imbalances in immunosurveillance mechanisms, including T-regulatory cells, are considered to play a crucial role.18-22 In addition, treatment-triggered autoimmune cytopenia was recognized in the first comprehensive descriptions of CLL.15,17 In the early 1990s, however, there was concern that treatment with purine analogs could, through their potent immunosuppressive effect, be associated with a higher frequency of AIHA that in some instances could eventually be fatal. These cases have been mainly observed in patients with active immune cytopenia and heavily pretreated.23-27 As a result of these observations, there is agreement that purine analogs should be avoided in patients with autoimmune cytopenia, particularly if related to purine analogs, or patients with active autoimmune cytopenia or DAT+ at study entry.

However, in patients with no prior history of AIHA there is evidence that the risk of developing this complication on exposure to purine analogs is not superior to that observed with other agents. In line with this notion, in our series 4% of 204 patients exposed to fludarabine-containing regimens presented autoimmune cytopenia compared with 5% of 231 patients treated with chlorambucil. This is in agreement with recent studies.28,29 Thus, as part of the UK LRF CLL4 trial analyses, Dearden et al29 reported on the incidence and prognostic significance of DAT positivity and overt clinically apparent AIHA in 777 patients with CLL. No differences in the percentage of patients becoming DAT+ after therapy (14% chlorambucil, 13% fludarabine, and 10% fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide) were observed. Notably, the incidence of AIHA was significantly lower in patients treated with fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide (5%) than in patients allocated to receive chlorambucil (12%) or fludarabine alone (11%; P < .01), suggesting that the addition of cyclophosphamide to fludarabine might have a “protective” effect on the appearance of AIHA.29 In another study from the M.D. Anderson group the incidence of AIHA in 300 patients (of which 8 had previously presented with AIHA) treated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab was 6.5%,28 and, in the recent German CLL8 trial, the global incidence of AIHA in 793 patients was < 1% with no significant differences between patients treated with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide with or without rituximab (Michael Hallek, University of Cologne, written communication, April 26, 2010).

From the clinical standpoint, male sex, older age, a high blood lymphocyte count, and advanced disease have been classically associated with autoimmune cytopenia.4,7,30 In conformity with these observations, in our series a high blood lymphocyte count at diagnosis and a short LDT (ie. < 12 months) correlated with the risk of developing autoimmune cytopenia. More recently, some studies have found an association between autoimmune cytopenia and unfavorable biomarkers, including unmutated IGHV genes,7,31-33 high expression of CD3834 or ZAP-70,7,35 and increased B2M serum levels.28,29,32 In our series we also found a correlation between increased serum B2M levels, high ZAP-70 or CD38 expression, and autoimmune cytopenia. Unfortunately, because of the retrospective nature of the study limited information was available for IGHV mutational status and cytogenetics, with this precluding a meaningful analysis on the basis of these latter parameters.

The most controversial issue for immune cytopenia in CLL is its prognostic significance.4,5,7,36 Mauro et al4 reported an association between disease activity and AIHA but no effect on survival. Two other reports evaluated the prognostic significance of the origin of cytopenia, concluding that, whereas cytopenia because of bone marrow failure confers poor prognosis, autoimmune cytopenia is not an adverse prognostic factor.5,36 More recently a multicenter study showed that patients with CLL and ITP had worse prognosis than patients who did not develop this complication probably because of a strong association between the development of ITP and poor prognostic variables (ie, unmutated IGHV).7,33

Against this background, we first investigated whether the occurrence of autoimmune cytopenia had any effect on the outcome of patients with CLL. Overall, in our series the development of autoimmune cytopenia at any time during the evolution of the disease did not significantly influence prognosis. Nevertheless, survival of patients in early stage (Binet A) and immune cytopenia was slightly worse (median, 9 years) than that of patients not presenting with this complication (median, 10 years). Although this difference was not statistically significant, it is of interest that an association between AIHA and progressive stage A disease was identified some years ago.37 In addition, the time at which autoimmune cytopenia was noticed (ie, at diagnosis, during the course of the disease) had no prognostic effect.

Rai et al8 and Binet et al9 systems do not take into account the origin of cytopenia to define clinical stages. We, therefore, analyzed the outcome of patients in advanced clinical stage (Binet C) at diagnosis according to the origin of the cytopenia, and we found that patients with cytopenia because of immune mechanisms (C immune) had longer survival than patients with stage C because of bone marrow infiltration (C infiltrative). Interestingly, this observation was first made > 20 years ago by Geisler and Hansen11 in a short series of patients and has been now confirmed in larger series of patients from the Mayo Clinic5 and our own study. The main reason for the better outcome of patients with cytopenias of immune origin relies on the response to therapy. Not surprisingly a large proportion of patients with stage C immune did respond to corticosteroids and, as a result, shifted to stage A. In contrast, only a small proportion of patients with stage C infiltrative did respond to therapy. Despite this, however, patients with stage C immune still had an inferior outcome than patients with stage A disease, their prognosis being closer to patients with stage B disease. Although the reasons for these findings are not entirely clear, autoimmune cytopenias correlated with poor prognostic variables; therefore, it is tempting to speculate that autoimmune phenomena are a fingerprint of a biologically more aggressive disease.

In conclusion, in this large, unselected and single institution series, which should therefore be considered as representative of the general population of subjects with CLL, the prevalence of autoimmune cytopenia was 7%. Autoimmune cytopenia correlated with well-known poor prognostic variables, including high blood lymphocyte count, short LDT, as well as high serum B2M level and high ZAP-70 and CD38 expressions, but not with treatment modality (fludarabine based vs alkylator based). From the prognostic point of view, the development of autoimmune cytopenia did not significantly influence prognosis in the whole group of patients. Importantly, however, patients presenting with advanced disease related to an immune mechanism had better prognosis than patients in whom advanced stage reflected a high tumor burden only. Therefore, determining the cause of cytopenia (immune vs infiltrative) is important not only for prognostic but also for therapeutic considerations. Finally, the different outcome of patients with advanced disease according to the origin of cytopenia, as shown in this study and others,5 also makes a case for including a stage C immune group in the prognostic categorization of patients with CLL.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa en Cáncer (grant RT 06/0020/002051), Spanish Ministry of Science, Instituto Carlos III (FISS PI080304), Generalitat de Catalunya (2009SGR1008), CLL Global Foundation, and Premi Distinció Generalitat de Catalunya (EM), and by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PFIS; G.F.).

Authorship

Contribution: C.M. designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; K.H. and G.F. analyzed the data and wrote part of the paper; M.E., X.F., and T.B. analyzed the data and the study results; A.P. performed the statistical analysis; and E.M. designed the study along with C.M., wrote the paper, and approved its final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for C.M. is M. D. Anderson International, Madrid, Spain.

Correspondence: Emili Montserrat, Hematology Department, Hospital Clínic, Villarroel 170, Barcelona 08036, Spain; e-mail address: emontse@clinic.ub.es.

References

Author notes

C.M., K.H., and G.F. contributed equally to this study.