Abstract

Influenza causes excess morbidity in sickle cell disease (SCD). H1N1 pandemic influenza has been severe in children. To compare H1N1 with seasonal influenza in SCD (patients younger than 22), we reviewed medical records (1993-2009). We identified 123 cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza (94 seasonal, 29 H1N1). Those with seasonal influenza were younger (median 4.4 vs 8.7 years old, P = .006) and had less asthma (24% vs 56%, P = .002). Those with H1N1 influenza more often had acute chest syndrome (ACS; 34% vs 13%, P = .01) and required intensive care (17% vs 3%, P = .02), including mechanical ventilation (10% vs 0%, P = .02). In multivariate analysis, older age (odds ratio [OR] 1.1 per year, P = .04) and H1N1 influenza (OR 3.0, P = .04) were associated with ACS, and older age (OR 1.1 per year, P = .02) and prior ACS (OR 3.3 per episode in last year, P < .006) with intensive care. Influenza, especially H1N1, causes critical illness in SCD and should be prevented.

Introduction

Influenza causes disproportionate morbidity in sickle cell disease (SCD), an inherited hemoglobinopathy affecting 1 in 2500 children in the United States.1 In one study, SCD was associated with a 56-fold increased risk of influenza-related hospitalization.2 Yet, despite its effectiveness,3,4 most children with SCD do not receive the influenza vaccine yearly.5 Recognition of the influenza A virus of swine origin (H1N1) in March 20096 caused heightened concern. Case series of H1N1 influenza in SCD have reported severe illness, with 10 in 21 children and 2 in 2 adults developing acute chest syndrome (ACS).7,8 To assess the relative severity of pandemic H1N1 versus seasonal influenza in SCD, we performed a comprehensive analysis at our institution.

Methods

Study population

We identified patients aged < 22 years with SCD and influenza by searching for SCD and respiratory virus testing from September 1, 1993, to April 30, 2007, in the discharge and billing databases of Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH). From May 1, 2007, to December 10, 2009, we also prospectively identified patients with SCD and influenza admitted to the pediatric hematology service or seen in the pediatric emergency department at JHH. We reviewed clinical records to identify influenza vaccination and administrative records to estimate the number of patients aged < 22 years with SCD seen at JHH. Additional information appears in supplemental data (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Definitions

We defined influenza as laboratory-confirmed influenza A or B and ACS as a new pulmonary infiltrate involving ≥ 1 complete lung segment with fever (> 38.5°C), tachypnea, cough, wheezing, or chest pain.9 We defined severe pain as pain requiring > 2 doses of opiates and asthma exacerbation as bronchodilator-treated wheezing.

Diagnosis of influenza

Influenza was detected by rapid antigen-based test (immunochromatographic membrane tests used until April 28, 2009), direct fluorescence antigen (DFA) test, and/or shell vial or conventional cell culture. Negative rapid antigen-based tests were confirmed with DFA and, if DFA-negative, by culture.10 The Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene performed real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction to confirm H1N1 influenza.11

Statistical analysis

We used Intercooled Stata 11.0 to compare continuous variables by Student t test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and we compared dichotomous variables by Fisher exact test. We used univariate and multivariate logistic regression with adjustment for clustering by patient to characterize associations. The Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the research.

Results and discussion

Clinical features

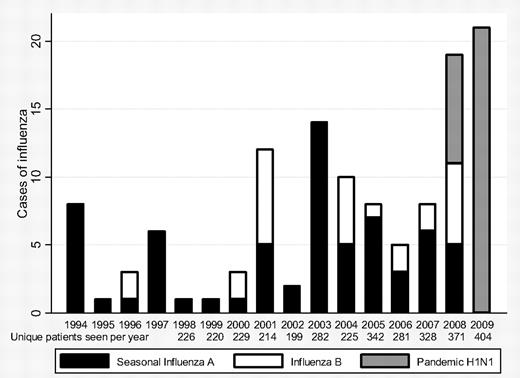

We identified 123 patients with SCD and laboratory-confirmed influenza, including 66 cases of seasonal influenza A, 28 of influenza B, and 29 of H1N1 influenza (Figure 1). Twenty-one of 29 cases of H1N1 influenza were confirmed by real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, 13 of 29 were identified by DFA, and 8 occurred when H1N1 influenza was the only locally circulating strain.

Number of cases of seasonal influenza A, influenza B, and pandemic H1N1 influenza in children and young adults (aged < 22 years) and unique patients seen per year, Johns Hopkins Hospital, 1993-2009.

Number of cases of seasonal influenza A, influenza B, and pandemic H1N1 influenza in children and young adults (aged < 22 years) and unique patients seen per year, Johns Hopkins Hospital, 1993-2009.

Patients with seasonal versus H1N1 influenza were younger and less likely to have asthma. Cough, fever, rhinorrhea, and dyspnea were common in both groups; wheezing and crackles were possibly less frequent with seasonal influenza; and retractions and nasal flaring were uncommon in both (Table 1). Among the 100 with sickle cell anemia, 3% had a WBC < 5000/μL, 8% platelets < 150 000/μL, and 4% relative reticulocytopenia (Hb < 9 g/dL and reticulocytes < 5%); there were no significant differences by type of influenza.

Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of children and young adults with seasonal influenza A and B or H1N1 influenza and sickle cell disease, Johns Hopkins Hospital, 1993-2009

| Variable . | Seasonal (n = 94) . | H1N1 (n = 29) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) age, years | 4.4 (1.8, 11) | 8.7 (4.9, 13) | .006 |

| Male sex | 59 | 59 | .99 |

| Hemoglobinopathy | |||

| HbSS or HbSβ0thal | 86 | 72 | |

| HbSC | 12 | 24 | |

| HbSβ+thal | 2 | 3 | |

| Chronic red blood cell transfusion therapy | 16 | 28 | .19 |

| History of asthma | 24 | 56 | .002 |

| Any influenza vaccination* | 54 | 67 | .36 |

| Fever (≥ 38.5°C) | 89 | 93 | .53 |

| Emesis | 25 | 29 | .64 |

| Cough | 93 | 93 | .99 |

| Headache | 34 | 48 | .42 |

| Wheezing | 7 | 21 | .07 |

| Crackles | 13 | 26 | .14 |

| Retractions | 8 | 9 | > .99 |

| Nasal flaring | 4 | 5 | > .99 |

| Median (IQR) body mass index, kg/m2† | 16.9 (15.6, 19.7) | 18 (16.4, 22.1) | .12 |

| Therapy with antibacterial agents | 96 | 93 | .63 |

| Therapy with antiviral agents | 36 | 79 | .0005 |

| Therapy with bronchodilators | 35 | 57 | .04 |

| Receipt of red blood cell transfusion | 14 | 34 | .03 |

| Hospitalization | 89 | 86 | .74 |

| Intensive care | 3 | 17 | .02 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0 | 10 | .02 |

| Acute chest syndrome | 13‡ | 34 | .01 |

| Severe pain | 11 | 29 | .03 |

| Asthma exacerbation | 7 | 21 | .03 |

| Median length of stay (IQR) | 2 days (1, 3) | 3 days (1, 5) | .05 |

| Variable . | Seasonal (n = 94) . | H1N1 (n = 29) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) age, years | 4.4 (1.8, 11) | 8.7 (4.9, 13) | .006 |

| Male sex | 59 | 59 | .99 |

| Hemoglobinopathy | |||

| HbSS or HbSβ0thal | 86 | 72 | |

| HbSC | 12 | 24 | |

| HbSβ+thal | 2 | 3 | |

| Chronic red blood cell transfusion therapy | 16 | 28 | .19 |

| History of asthma | 24 | 56 | .002 |

| Any influenza vaccination* | 54 | 67 | .36 |

| Fever (≥ 38.5°C) | 89 | 93 | .53 |

| Emesis | 25 | 29 | .64 |

| Cough | 93 | 93 | .99 |

| Headache | 34 | 48 | .42 |

| Wheezing | 7 | 21 | .07 |

| Crackles | 13 | 26 | .14 |

| Retractions | 8 | 9 | > .99 |

| Nasal flaring | 4 | 5 | > .99 |

| Median (IQR) body mass index, kg/m2† | 16.9 (15.6, 19.7) | 18 (16.4, 22.1) | .12 |

| Therapy with antibacterial agents | 96 | 93 | .63 |

| Therapy with antiviral agents | 36 | 79 | .0005 |

| Therapy with bronchodilators | 35 | 57 | .04 |

| Receipt of red blood cell transfusion | 14 | 34 | .03 |

| Hospitalization | 89 | 86 | .74 |

| Intensive care | 3 | 17 | .02 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0 | 10 | .02 |

| Acute chest syndrome | 13‡ | 34 | .01 |

| Severe pain | 11 | 29 | .03 |

| Asthma exacerbation | 7 | 21 | .03 |

| Median length of stay (IQR) | 2 days (1, 3) | 3 days (1, 5) | .05 |

IQR indicates interquartile range; HbSS, sickle cell anemia; HbSβ0 thal, sickle-β–null thalassemia; Hbsβ+ thal, sickle-β–plus thalassemia; and HbSC, sickle-hemoglobin C disease. Data are presented as percentages unless otherwise indicated.

Missing vaccination status for 37 with seasonal and 11 with epidemic influenza.

Missing body mass index for 36 with seasonal and 4 with epidemic influenza.

Excludes 8 patients without chest x-rays (low clinical suspicion of acute chest syndrome).

Up-to-date vaccination against seasonal influenza A was documented for 54% with seasonal and 67% with H1N1 influenza; only 3 (17%) were vaccinated against H1N1 influenza. Vaccination was not associated with reduced severity of illness.

Treatment and outcomes

Most patients with H1N1 and seasonal influenza were hospitalized, but those with H1N1 influenza more often developed ACS, severe pain, and illness requiring intensive care (Table 1). Those with H1N1 influenza more often received antiviral agents, red blood cell transfusions, and exchange transfusions (10% vs 3%, P = .045). No patient died.

Age and H1N1 influenza predictated ACS in unadjusted and adjusted models including age, H1N1 versus seasonal influenza, asthma, hydroxyurea use, and ACS episodes (past year). The adjusted odds of ACS were 1.1 per year of age (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.0-1.2, P = .04) and 3.0 for H1N1 influenza (95% CI 1.1-8.5, P = .04). In models including the same variables, 4 factors (age, H1N1 influenza, hydroxyurea use, and ACS in the past year) predicted intensive care in the unadjusted model and 2 (age and ACS in the past year) in the adjusted model (supplemental Table 1). The adjusted odds of requiring intensive care were 1.2 per year of age (95% CI 1.0-2.1, P = .02) and 13.0 for H1N1 influenza (95% CI 2.1-82, P = .006).

Epidemiology

Between 1993 and 2008, 0-13 (mean 5.9) patients per year were hospitalized with seasonal influenza. Seventy-four patients had seasonal influenza before 2007 and 19 in 2007-2008; although clinical illness was similar, a greater proportion (33% vs 9%, P = .03) received a red blood cell transfusion in 2007-2008 versus pre-2007. From May to December 2009, 25 patients were hospitalized with H1N1 influenza.

We found influenza in SCD to be clinically similar (except for more frequent cough and headache) to that reported in other children.12 The high proportion hospitalized reflects the standard practice of admitting most patients who are febrile and < 3 years old and all patients who have a high fever (≥ 40°C) or pulmonary infiltrates.13 The frequency of severe illness despite prompt treatment and supportive care underscores the importance of preventing influenza.

We also found H1N1 to be more severe than seasonal influenza in SCD and clinically similar (except for more cough and higher fever) to H1N1 influenza reported in pediatric dependents of military personnel.14 One series of 54 children hospitalized with H1N1 (9 with hemoglobinopathy) and 200 with seasonal influenza (22 with hemoglobinopathy) suggested that H1N1 influenza was not more severe than seasonal influenza.15 However, our clinical findings are supported by the high mortality (319 pediatric deaths) from H1N1 influenza reported in the United States from April 2009 to January 2010 compared with that from seasonal influenza previously (78 deaths in 2006-2007, 88 in 2007-2008).

The relative severity of H1N1 versus seasonal influenza in young patients with SCD may reflect decreased pre-existing immunity and limited vaccination. In a H1N1 vaccine study including healthy children and young adults, most had no immunity to this nor similar influenza viruses (< 5% had a protective hemagglutination-inhibition titer of > 1:40 before immunization).16 Furthermore, the monovalent H1N1 influenza vaccine was not widely available before November 2009.

Limitations of our study include retrospective identification of 1993-2007 seasonal influenza versus prospective identification in 2009 and case ascertainment-related bias toward more severe disease. We were more likely to identify those with fever (≥ 38.5°C) and respiratory symptoms because we urgently evaluate febrile patients with SCD and routinely send samples for respiratory viral testing from symptomatic patients in the late fall and winter. Strengths of our study are the use of multiple methods to identify cases, rigorous diagnostic confirmation, and the large number of cases identified.

In conclusion, we found that influenza, especially H1N1, causes frequent severe illness in patients with SCD. Critical illness was especially common in older patients with prior ACS. Programs to increase vaccination against influenza in patients with SCD and their household contacts are imperative. Vaccination against H1N1 is particularly important given the low level of pre-existing immunity, frequent complications, and the immunogenicity and availability of several vaccines.16-18 Because the H1N1 strain will be included in the seasonal influenza vaccine in the 2010-2011 season, vaccinating those at risk should be achievable with concerted effort.19 Although not proven to reduce morbidity or mortality in SCD, the use of antiviral treatments and, when epidemiologically appropriate, chemoprophylaxis is recommended in this vulnerable population.10

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maria Paz Carlos, Robert Myers, and the virology staff of the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the medical technologists in the virology section of the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of Johns Hopkins Hospital for their contributions.

J.J.S. was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5K23HL078819-03), the American Society of Hematology, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. M.E.R. was supported by a Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Clinician Scientist Career Development award and the National Center for Infectious Diseases (1K23 AI083931-01A1). D.G.B. was supported by the Physician Faculty Scholars Program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. This project was also supported in part by Award U54HL090515 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J.J.S., M.E.R., M.C., and J.F.C. designed research; J.J.S., M.E.R., M.A., M.C., R.N.H., and A.V. performed research; J.J.S., M.E.R., and R.N.H. analyzed and/or interpreted data; and J.J.S., M.E.R., D.G.B., A.V., and J.F.C. wrote and/or critically revised the manuscript. All of the authors have seen and approved of the submission of this version of the manuscript and take full responsibility for the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: John J. Strouse, 200 N Wolfe St, Rubenstein Bldg, Rm 3006, Baltimore, MD 21287; e-mail: jstrous1@jhmi.edu.