Abstract

Expression of protein kinase CK2 is frequently deregulated in cancer and mounting evidence implicates CK2 in tumorigenesis. Here, we show that CK2 is overexpressed and hyperactivated in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Inhibition of CK2 induces apoptosis of CLL cells without significantly affecting normal B and T lymphocytes. Importantly, this effect is not reversed by coculture with OP9 stromal cells, which are otherwise capable of rescuing CLL cells from in vitro spontaneous apoptosis. CLL cell death upon CK2 inhibition is mediated by inactivation of PKC, a PI3K downstream target, and correlates with increased PTEN activity, indicating that CK2 promotes CLL cell survival at least in part via PI3K-dependent signaling. Although CK2 antagonists induce significant apoptosis of CLL cells in all patient samples analyzed, sensitivity to CK2 blockade positively correlates with the percentage of CLL cells in the peripheral blood, β2 microglobulin serum levels and clinical stage. These data suggest that subsets of patients with aggressive and advanced stage disease may especially benefit from therapeutic strategies targeting CK2 function. Overall, our study indicates that CK2 plays a critical role in CLL cell survival, laying the groundwork for the inclusion of CK2 inhibitors into future therapeutic strategies.

Introduction

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in the Western world and is characterized by the accumulation of mature, monoclonal B lymphocytes in the blood, bone marrow, and secondary lymphoid organs.1 The expansion of CLL malignant B cells appears to result mainly from a decrease in apoptosis.2 Clinically, CLL is a very heterogeneous disease with overall survival raging from a few years to decades. Prognostic indicators include immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IgVH) mutation status, cytogenetic abnormalities, clinical stage, lymphocyte doubling time, leukocyte counts, serum lactate dehydrogenase and β2 microglobulin levels, and ZAP-70 and CD38 expression.3 Despite significant advances CLL is still an incurable disease,1 and the identification of new therapeutic strategies is warranted. Characterization of the molecular mechanisms that regulate leukemia cell viability may provide novel insights into the biology of this malignancy and reveal prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. In particular, specific inhibition of signaling elements essential for leukemia cell survival offers great promise for the design of more efficient and selective therapies.

The ubiquitous serine/threonine protein kinase CK2, a tetramer consisting of 2 catalytic (α and/or α′) and 2 regulatory β subunits, is highly pleiotropic and intervenes laterally on many signaling pathways.4,5 CK2 can drive tumorigenesis by different mechanisms, playing a global antiapoptotic role, enhancing multidrug resistance, activating the chaperone machinery that protects the oncokinome, and sustaining neo-vascularization.6 Overexpression of CK2 has been consistently observed in human cancers, including lung,7 kidney,8 head and neck,9 prostate,10 and breast.11 Importantly, inhibition of CK2 activity, using specific pharmacologic inhibitors or silencing the catalytic subunit, has been shown to decrease the survival of multiple myeloma,12 acute myeloid leukemia,13 and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia14 cells. In CLL, the genes that code for CK2α (CSNK2A1) and CK2β (CSNK2B) were identified as a part of a poor prognosis cluster associated with shorter treatment-free survival.15

Primary CLL cells display constitutive activation of PI3K kinase activity,16 which appears to be critical for CLL cell survival.17,18 PTEN, the main negative regulator of PI3K signaling pathway, can be phosphorylated by CK2 at the C terminus, leading to PTEN functional inactivation and concomitant increased protein stability.19 We recently showed that CK2 overexpression/hyperactivation in primary T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells induces PTEN nondeletional posttranslational inactivation by phosphorylation and consequent PI3K pathway hyperactivation.14 However, the relative expression and functional impact of CK2 in CLL remains to be established.

In the current study, we demonstrate that CK2 plays a critical role in the maintenance of CLL cell viability. Primary CLL cells displayed significantly higher CK2 expression and activity than normal B cells. Furthermore, inhibition of CK2 activity induced apoptosis of leukemia cells without a significant impact on normal lymphocytes, and this effect was not prevented by coculture with stromal cells. The positive effect of CK2 on CLL cell survival correlated with PTEN phosphorylation, which is indicative of PTEN functional inactivation, and was dependent on phosphorylation/activation of PKC, a major PI3K signaling pathway effector. Interestingly, the sensitivity of primary CLL cells to CK2 inhibition positively correlated with the percentage of malignant cells in the peripheral blood, and CLL cells from patients classified as Binet stage B or C were more susceptible to CK2 inhibition than those from Binet A. Overall, our data indicate that CK2 may be a novel, valid target for therapeutic intervention in CLL, whose inhibition may especially benefit patients with advanced disease.

Methods

Patient and healthy control samples

Sixty-three patients and 15 age-matched healthy donors were studied. CLL was diagnosed according to the NCI-WG updated guidelines.20 Median age of the patients was 73 years (range, 40-90 years), and 69% were male. Eighty-five percent were previously untreated and the others received prior alkylating and/or purine analog therapy more than one year before entering the study. Peripheral blood samples from CLL patients and healthy controls were collected after informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and under ethical approval of Instituto Português de Oncologia (Lisbon, Portugal). Supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) summarizes the clinical and biologic characteristics of the patients analyzed.

Cell isolation

Peripheral blood from CLL patients and healthy controls was enriched in mononuclear cells by Ficoll density grade centrifugation (Amersham Biosciences). In some experiments, either malignant or normal B cells were subsequently purified using anti-CD19 antibodies coupled to magnetic beads using MiniMacs or MidiMacs (Miltenyi Biotec). In other experiments, cells were isolated from peripheral blood using RosetteSep human B-cell enrichment cocktail (StemCell Technologies) as indicated by the manufacturer. The purity of CLL cells and normal B cells, evaluated by staining with anti-CD5, -CD3, and -CD19 fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (eBioscience) followed by flow cytometric analysis using a FACSCanto flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson), was always higher than 90%.

Cell culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from CLL patients or healthy donors, and isolated CLL cells or lymphocytes from healthy controls were cultured as 2 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 2mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, .1 mg/mL streptomycin (hereafter referred to as glut-pen/strep) and 1% heat-inactivated FBS (Invitrogen). In some experiments, CLL cells were cocultured with the murine stromal cell line OP9.21 OP9 stromal cells were seeded in a 24-well plate as 105 cells/well in DMEM supplemented with 25mM glucose, 1mM sodium pyruvate, glut-pen/strep and 10% heat-inactivated FBS. After overnight culture, the confluence of the stromal layer was assessed by microscopy, the culture medium was removed, and 106 CLL cells were added to each well under the culture conditions described above. MEC122 and JVM-323 cell lines were cultured as 5 × 105 cells/mL in IMDM or 2 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI, respectively, supplemented with glut-pen/strep and 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Where specified, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of TBB (Merck), DRB (Sigma-Aldrich), CX-4945 (Cylene Pharmaceuticals), QVD-OPH (BioVision), and PMA (Sigma-Aldrich).

Analysis of cell viability and apoptosis

Cell viability was determined by double-staining with APC-conjugated annexin V (eBioscience) and 7-AAD (Becton Dickinson) followed by flow cytometric analysis on a FACSCanto flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 100 μL of binding buffer with annexin V and 7-AAD. After 15 minutes of incubation at room temperature in the dark, 100 μL of binding buffer were added and the samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. Fully viable cells were identified as the annexin V and 7-AAD double-negative population. Nonpurified PBMCs were stained with anti-CD3 APC-Cy7, CD5 FITC, and CD19 PE-Cy7 conjugated antibodies (eBioscience) to identify the distinct subpopulations.

Immunoblot

Cells were lysed and immubloting was performed as described,24 using the following antibodies: actin, CK2α, CK2β, caspase3, PKC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PARP (Novus Biologicals), P-PTEN (S380), PTEN, P-PKCβ (S660) and P-PKCδ (T505; Cell Signaling Technology). Where indicated, densitometry analysis was performed using Adobe Photoshop CS3 Extended software (version 10.0). Each band was analyzed with a constant frame and normalized to the respective loading control.

In vitro CK2 kinase assay

CK2 activity was measured using the Casein Kinase 2 Assay Kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 15 μg of protein lysate were incubated for 10 minutes at 30°C in a reaction mixture containing a CK2-specific peptide, [γ-32P]ATP and a PKA inhibitor cocktail. The radioactivity incorporated into the substract was determined by scintillation counting. The kinase activity was calculated by subtracting the background for each sample (without substrate).

siRNA nucleofection

MEC1 cells (2.5 × 106), resuspended in 100 μL of Cell line Solution Kit V (Lonza Group), were transfected with 2μM ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool CK2α siRNA or ON-TARGETplus siCONTROL nontargeting pool as negative control (Dharmacon) using the Amaxa Nucleofector device II (program X-001).

Phenotypic and genetic features of CLL patients

Flow cytometric analysis was performed as described.25 Neoplastic B cells were phenotypically identified by the coexpression of CD19 and CD5, and light chain restriction. CD38 expression was determined in the neoplastic population using anti-CD38 conjugated either with PE or APC-H7 (Becton Dickinson) and patients were considered as CD38-positive when the percentage of CD38+ cells exceeded 30%. To determine ZAP-70 expression, PBMCs were fixed and permeabilized with the Cytofix/Cytoperm solutions (Becton Dickinson), incubated with anti–ZAP-70 antibody (Caltag Laboratoies) and labeled with anti-CD19 and anti-CD3 antibodies (eBioscience). The cutoff value for ZAP-70 positivity was set at 20%. Positivity was defined by MFI CLL/T cell ZAP-70 expression ratio. Cytogenetic abnormalities were assessed by fluorescent in situ hybridization using probes for del13q14 (LSI D13S319), tris12 (CEP12), del11q22 (LSI ATM), and del17p13 (LSI p53). Analysis of IGHV genes was performed in DNA obtained from either bone marrow or peripheral blood mononuclear cells. DNA amplification using FR1 primers was done in 6 PCR reactions and based on the BIOMED-2 protocols.26 PCR products were sequenced on an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) after heteroduplex analysis and excision of clonal bands. Sequence data were analyzed on the IMGT database (http://imgt.cines.fr) according to European Research Initiative on CLL (ERIC) recommendations.27 Sequences with a germline identity of 98% or higher were classified as unmutated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software). Statistical differences between mean values were evaluated using the 2-tailed Student t test (paired or unpaired, as appropriate). Relations between variables were assessed by Pearson correlation. Differences and correlations were considered significant for P values less than .05.

Results

CK2 is overexpressed and hyperactivated in CLL cells

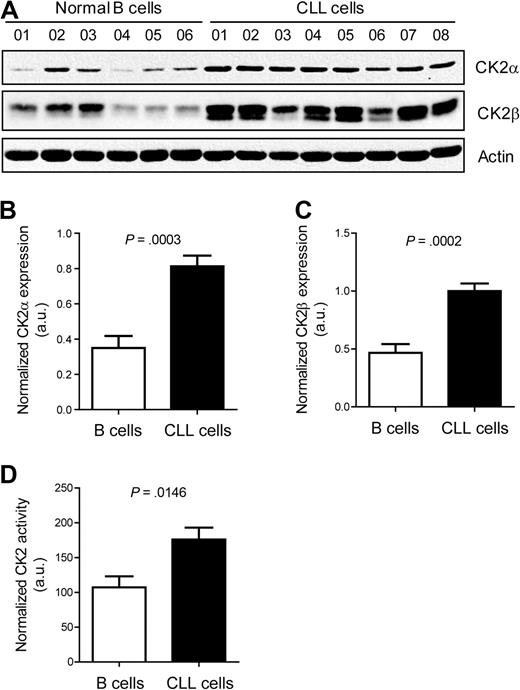

CK2 has been implicated in the development of different cancers, including hematologic tumors. To investigate whether CK2 might play a role in CLL, we first analyzed the expression of CK2 in isolated CD19+ cells from untreated CLL patients (n = 8) and isolated B cells from healthy donors (n = 6) by Western blot. Both CK2α and CK2β were clearly up-regulated in CLL cells compared with normal B cells (Figure 1A-C; P = .0003 and P = .0002, respectively; unpaired 2-tailed t test). Moreover, CLL cells displayed significantly higher CK2 kinase activity than normal B cells (P = .0146; Figure 1D).

CLL cells display significantly higher CK2 expression and activity than normal B cells. (A) Cell lysates of isolated primary CLL cells collected at diagnosis or isolated normal B cells from healthy donors were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against CK2α, CK2β, or actin as loading control. Relative expression of CK2α (B) and CK2β (C) was quantified by densitometry analysis and is expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.). (D) CK2 activity was measured by an in vitro kinase assay in CLL cells (n = 8) and normal B cells (n = 6). Results shown as mean ± SEM.

CLL cells display significantly higher CK2 expression and activity than normal B cells. (A) Cell lysates of isolated primary CLL cells collected at diagnosis or isolated normal B cells from healthy donors were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against CK2α, CK2β, or actin as loading control. Relative expression of CK2α (B) and CK2β (C) was quantified by densitometry analysis and is expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.). (D) CK2 activity was measured by an in vitro kinase assay in CLL cells (n = 8) and normal B cells (n = 6). Results shown as mean ± SEM.

CLL cells rely on CK2 activity to maintain their viability

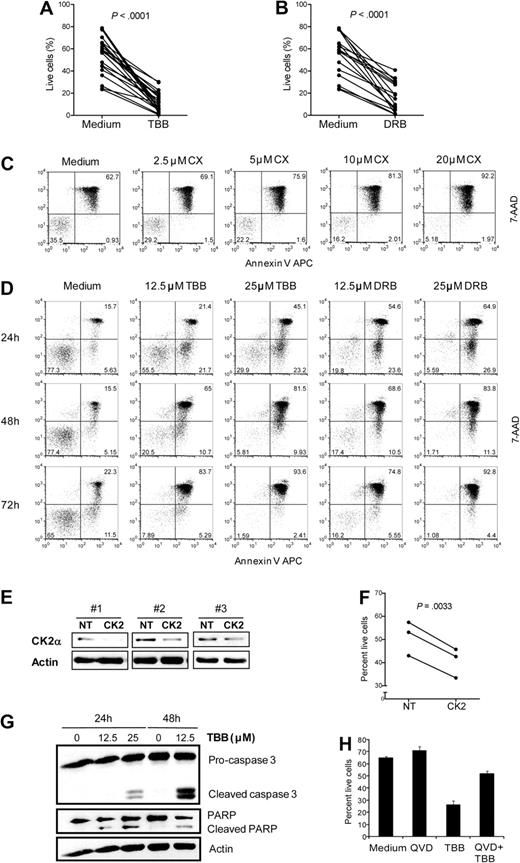

To test the functional impact of CK2 overexpression and hyperactivation on CLL cell viability, we cultured isolated primary leukemia cells in the presence of the CK2-specific small molecule inhibitors28 TBB (n = 22) and DRB (n = 17). Both CK2 inhibitors induced cell death in all patient samples tested (P < .0001, Figure 2A-B; see supplemental Table 1 for the complete list of patients included in the study and their clinical and biologic characteristics). These results were confirmed with CX-4945, a highly selective small-molecule inhibitor of CK2 which is currently under evaluation in phase 1 clinical trials in solid tumors (Figure 2C). Sensitivity of primary CLL cells to CK2 inhibition was time- and dose-dependent, as assessed by annexin V/7AAD staining (Figure 2C,D). To confirm the results obtained with the pharmacologic inhibitors, we used siRNA against CK2α to specifically downmodulate CK2 expression in the CLL cell line MEC1. Similarly to primary leukemia cells, MEC1 cells are sensitive to CK2 small molecule inhibitors (supplemental Figure 1A-C). Likewise, knock down of CK2α (Figure 2E) resulted in a significant decrease in cell viability (P = .0033; Figure 2F). To confirm that death of CLL cells upon CK2 inhibition was due to increased apoptosis, we evaluated caspase 3 activation and PARP cleavage by Western blot. Treatment with TBB induced cleavage of pro-caspase 3 and PARP in primary CLL cells (Figure 2G) and cell lines (data not shown). Moreover, pretreatment with the pan-caspase inhibitor QVD significantly prevented TBB-mediated CLL cell death (Figure 2H). These results clearly indicate that CK2 is essential to maintain CLL cell viability in vitro and that CK2 inhibition results in apoptosis of CLL cells.

CK2 inhibition induces apoptosis of CLL cells. Primary CLL cells were cultured for 48 hours in medium alone or with (A) 25μM TBB (n = 22) or (B) 25μM DRB (n = 17) and cell viability was evaluated after 48 hours. (C) CLL cells were incubated with the indicated doses of CX-4945 and viability was assessed at 48 hours. Results are representative of 5 patients analyzed. (D) CLL cells were incubated without or with TBB (12.5μM, 25μM) or DRB (12.5μM, 25μM) and viability was assessed at 24, 48, and 72 hours. Results are representative of 11 patients analyzed. (C-D) The percentage of live (bottom left), early apoptotic (bottom right), and late apoptotic/necrotic (top right) cells is indicated in the respective quadrants. (E-F) MEC1 cells were nucleofected with control (NT) or CK2α siRNA (CK2) and cultured for 72 hours. A total of 3 independent experiments are shown. (E) Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against CK2α or actin. (F) Viability of MEC1 nucleofected with control vs CK2α siRNA was analyzed at 72 hours. Results for each independent experiment are shown. (G) CLL cells were cultured with TBB (12.5μM, 25μM) for 24 and 48 hours. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against caspase 3, PARP, or actin, as loading control. Results are representative of 3 patients analyzed. (H) CLL cells were preincubated with 20μM QVD-OPH for 1 hour and then cultured with 12.5μM TBB for 48 hours. Results are shown as mean ± SEM of triplicates and are representative of 3 patients analyzed. Cell viability was assessed by annexin V/7-AAD staining. Results are representative of 3 patients analyzed. (A-H) All evaluations of cell viability were performed by flow cytometric analysis after annexin V/7-AAD staining.

CK2 inhibition induces apoptosis of CLL cells. Primary CLL cells were cultured for 48 hours in medium alone or with (A) 25μM TBB (n = 22) or (B) 25μM DRB (n = 17) and cell viability was evaluated after 48 hours. (C) CLL cells were incubated with the indicated doses of CX-4945 and viability was assessed at 48 hours. Results are representative of 5 patients analyzed. (D) CLL cells were incubated without or with TBB (12.5μM, 25μM) or DRB (12.5μM, 25μM) and viability was assessed at 24, 48, and 72 hours. Results are representative of 11 patients analyzed. (C-D) The percentage of live (bottom left), early apoptotic (bottom right), and late apoptotic/necrotic (top right) cells is indicated in the respective quadrants. (E-F) MEC1 cells were nucleofected with control (NT) or CK2α siRNA (CK2) and cultured for 72 hours. A total of 3 independent experiments are shown. (E) Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against CK2α or actin. (F) Viability of MEC1 nucleofected with control vs CK2α siRNA was analyzed at 72 hours. Results for each independent experiment are shown. (G) CLL cells were cultured with TBB (12.5μM, 25μM) for 24 and 48 hours. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against caspase 3, PARP, or actin, as loading control. Results are representative of 3 patients analyzed. (H) CLL cells were preincubated with 20μM QVD-OPH for 1 hour and then cultured with 12.5μM TBB for 48 hours. Results are shown as mean ± SEM of triplicates and are representative of 3 patients analyzed. Cell viability was assessed by annexin V/7-AAD staining. Results are representative of 3 patients analyzed. (A-H) All evaluations of cell viability were performed by flow cytometric analysis after annexin V/7-AAD staining.

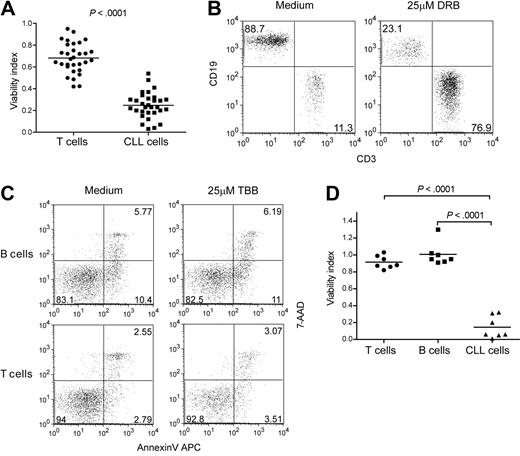

CK2 inhibition preferentially targets the viability of CLL cells without significantly affecting normal B and T cells

The striking effect of CK2 inhibition on the viability of CLL cells suggested that CK2 may constitute a valid molecular target for therapeutic intervention. To further investigate this possibility, we asked whether the CK2 pharmacologic inhibitors were selective toward leukemia cells. First, we cultured PBMCs collected from CLL patients with TBB (n = 40) or DRB (n = 31) for 48 hours to compare the effect on viability of CLL versus T cells within each patient sample. Cell death was consistently and strikingly higher in CLL cells than in normal T cells (Figure 3A and supplemental Figure 2A), originating a dramatic increase in the percentage of the latter (Figure 3B and supplemental Figure 2B). However, we noticed that the CK2 inhibitors also affected T-cell viability, particularly at higher doses (supplemental Figure 2A). This may reflect the reciprocal interaction between the malignant B cells and leukemia-subverted T cells that has been described in CLL.29 In agreement with this possibility, we found that the viability of normal B and T lymphocytes collected from age-matched healthy controls was not affected by either TBB (Figure 3C-D) or DRB (supplemental Figure 2C-D). These results indicate that CK2-specific small molecule inhibitors can selectively target leukemia cells.

CK2 inhibition selectively targets the viability of CLL cells without significantly affecting normal lymphocytes. (A-B) PBMCs from CLL patients (n = 31) were cultured with 25μM DRB and viability of T cells and CLL cells was assessed after 48 hours. (A) Viability index, calculated as the ratio between viable cells in medium with and without CK2 inhibitor, was compared between T and CLL cells within each patient sample. (B) CD3/CD19 phenotype of viable (annexin V/7-AAD double-negative) PBMCs from a representative CLL patient. CD3+CD19−, T cells; CD3−CD19+ CLL cells. Numbers represent the percentage of cells in each quadrant. (C-D) PBMCs from CLL patients (n = 7) and age-matched healthy controls (n = 7) were cultured for 48 hours with or without 25μM TBB. (C) Viability of normal B and T cells was determined by annexin V/7-AAD staining. Results from one representative healthy donor are shown. Numbers represent the percentage of cells in each quadrant. (D) Viability index was compared between normal T and B cells from healthy donors and leukemic B cells from CLL patients.

CK2 inhibition selectively targets the viability of CLL cells without significantly affecting normal lymphocytes. (A-B) PBMCs from CLL patients (n = 31) were cultured with 25μM DRB and viability of T cells and CLL cells was assessed after 48 hours. (A) Viability index, calculated as the ratio between viable cells in medium with and without CK2 inhibitor, was compared between T and CLL cells within each patient sample. (B) CD3/CD19 phenotype of viable (annexin V/7-AAD double-negative) PBMCs from a representative CLL patient. CD3+CD19−, T cells; CD3−CD19+ CLL cells. Numbers represent the percentage of cells in each quadrant. (C-D) PBMCs from CLL patients (n = 7) and age-matched healthy controls (n = 7) were cultured for 48 hours with or without 25μM TBB. (C) Viability of normal B and T cells was determined by annexin V/7-AAD staining. Results from one representative healthy donor are shown. Numbers represent the percentage of cells in each quadrant. (D) Viability index was compared between normal T and B cells from healthy donors and leukemic B cells from CLL patients.

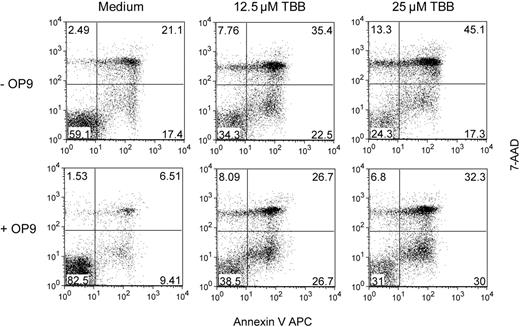

CLL cell death induced by CK2 inhibition is not reversed by stromal support

Because CLL cells rely on extracellular cues to maintain their viability,30 and the microenviroment can contribute to leukemia resistance against chemotherapy,31 we next sought to determine whether stroma would confer leukemia cell resistance against CK2 pharmacologic inhibitors. We cocultured isolated CLL cells with OP9 stromal cells in the presence or absence of TBB and evaluated cell survival by flow cytometry analysis of annexin V/7-AAD stained cells. Although stromal cells clearly increased the survival of CLL cells, they were unable to prevent apoptosis of leukemia cells treated with the CK2 inhibitor (Figure 4). These data suggest that the effects of inhibition of CK2 upon CLL cells are not counterbalanced by microenvironmental signals, further emphasizing the potential clinical relevance of targeting CK2 in CLL.

CK2 inhibition overcomes the protective effect of OP9 stromal cells. Purified CLL cells were cultured alone (−OP9) or cocultured with OP9 stromal cells (+OP9), and treated or not with the indicated doses of TBB. Viability was assessed after 48 hours by annexin V/7-AAD staining and flow cytometric analysis. Results are representative of 4 patients analyzed. Numbers represent the percentage of cells in each quadrant.

CK2 inhibition overcomes the protective effect of OP9 stromal cells. Purified CLL cells were cultured alone (−OP9) or cocultured with OP9 stromal cells (+OP9), and treated or not with the indicated doses of TBB. Viability was assessed after 48 hours by annexin V/7-AAD staining and flow cytometric analysis. Results are representative of 4 patients analyzed. Numbers represent the percentage of cells in each quadrant.

Apoptosis of CLL cells upon CK2 inhibition correlates with PTEN activation and is mediated by inactivation of PKC

CK2 promotes viability of primary acute leukemia T cells by phosphorylating and thereby inactivating PTEN, which results in hyperactivation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.14 We next analyzed whether similar mechanisms prevail in CLL. Although isolated malignant B cells collected from CLL patients and purified normal B cells from age-matched healthy controls presented similar PTEN protein expression levels, we found that CLL cells displayed significantly higher phosphorylated PTEN than normal controls (P = .0013; Figure 5A,B). It is well established that PTEN phosphorylation at the C-terminus negatively regulates PTEN phosphatase activity.14,32,33 Thus, our results indicate that PTEN phosphatase activity is constitutively down-regulated in CLL cells compared with their normal counterparts. Treatment with TBB resulted in decreased PTEN phosphorylation (Figure 5E) in both primary CLL cells (n = 10) and the JVM-3 cell line, which also enters apoptosis upon CK2 inhibition (supplemental Figure 1C-D). Similarly, MEC1 cells nucleofected with siRNA against CK2α showed reduced levels of phospho-PTEN. These results demonstrate that CK2 activity was responsible for PTEN inactivation in CLL cells.

CK2 inhibition-dependent apoptosis of CLL cells correlates with PTEN activation and relies on inactivation of PKC. (A) Cell lysates of normal B cells from healthy donors or primary CLL cells collected at diagnosis were purified and immunoblotted with antibodies against P-PTEN(S380), PTEN, P-PKCβ(S660), P-PKCδ(T550), PKC, or actin as loading control. (B-D) Expression of P-PTEN relative to total PTEN (B) and expression of P-PKCβ (C) and P-PKCδ (D) relative to total PKC was quantified by densitometry analysis. Results are shown as mean ± SEM. (E) Primary CLL cells or JVM-3 cells were incubated with 25μM and 50μM TBB, respectively, and lysed after 2 hours. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against the indicated proteins and their phosphorylated forms. P-PTEN results are representative of 10 patients analyzed. P-PKC results are representative of 2 patients analyzed. JVM3 results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) MEC1 cells were nucleofected with control versus CK2α siRNA and analyzed at 72 hours for the expression/phosphorylation of the indicated proteins by immunoblot. (G) Primary CLL cells were preincubated with 100nM PMA for 2 hours and then cultured with 12.5μM TBB for 48 hours. Cell viability was assessed by annexin V/7-AAD staining. Results are shown as mean ± SEM of triplicates and are representative of 4 patients analyzed.

CK2 inhibition-dependent apoptosis of CLL cells correlates with PTEN activation and relies on inactivation of PKC. (A) Cell lysates of normal B cells from healthy donors or primary CLL cells collected at diagnosis were purified and immunoblotted with antibodies against P-PTEN(S380), PTEN, P-PKCβ(S660), P-PKCδ(T550), PKC, or actin as loading control. (B-D) Expression of P-PTEN relative to total PTEN (B) and expression of P-PKCβ (C) and P-PKCδ (D) relative to total PKC was quantified by densitometry analysis. Results are shown as mean ± SEM. (E) Primary CLL cells or JVM-3 cells were incubated with 25μM and 50μM TBB, respectively, and lysed after 2 hours. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against the indicated proteins and their phosphorylated forms. P-PTEN results are representative of 10 patients analyzed. P-PKC results are representative of 2 patients analyzed. JVM3 results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) MEC1 cells were nucleofected with control versus CK2α siRNA and analyzed at 72 hours for the expression/phosphorylation of the indicated proteins by immunoblot. (G) Primary CLL cells were preincubated with 100nM PMA for 2 hours and then cultured with 12.5μM TBB for 48 hours. Cell viability was assessed by annexin V/7-AAD staining. Results are shown as mean ± SEM of triplicates and are representative of 4 patients analyzed.

Because PTEN is the main negative regulator of PI3K-dependent signaling, we next determined the impact of CK2 inhibition on PI3K downstream targets. A decrease in P-Akt was observed in 2 patient samples (data not shown). However, most CLL patient specimens we analyzed showed levels of Akt S473 and T308 phosphorylation similar to normal B cells from healthy controls (data not shown). We therefore hypothesized that a PI3K downstream target other than Akt played a role in promoting CK2-mediated leukemia cell viability in CLL. PI3K regulates PKC phosphorylation34 and PKCδ was shown to be constitutively activated in primary CLL cells in a PI3K-dependent manner.35 Moreover, inhibition of PKCδ by the specific inhibitor Rottlerin35 or by siRNA-mediated knock down36 induced apoptosis of CLL cells. In addition, PKCβ demonstrated to be essential for the development of CLL in mice and for the maintenance of primary CLL cell viability.37 We confirmed that most CLL patient samples displayed significantly increased phosphorylation of both PKCβ and PKCδ (P < .0001 and P = .0288, respectively; Figure 5A,C-D), at residues which reflect increased PKC kinase activity.38 Thus, we assessed the impact of CK2 inhibition on phospho-PKC levels as a measure of PKC activity. Treatment with TBB clearly down-regulated phospho-PKCβ and phospho-PKCδ in CLL primary cells (n = 2) and in the JVM-3 cell line (Figure 5E). Similar results were obtained upon CK2α knock down in MEC1 cells (Figure 5F). To clarify whether PKC activity was mandatory for CK2-dependent viability of CLL cells, we evaluated whether PMA, which directly activates PKC, was able to bypass the proapoptotic effects of TBB. Our results showed that incubation with PMA completely abrogated primary CLL cell death originated by CK2 inhibition (Figure 5G).

Primary CLL cells from patients with advanced stage disease are more sensitive to CK2 inhibition

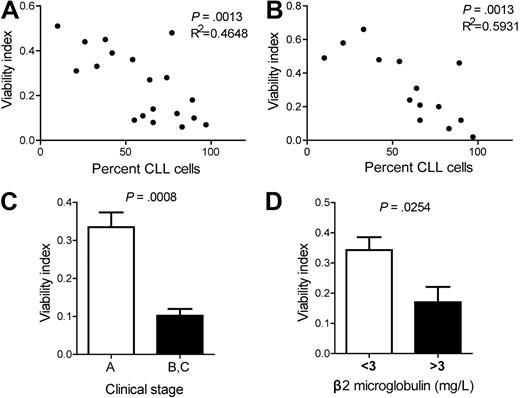

Although CK2 inhibition decreased CLL cell survival in all patient samples analyzed, we investigated whether the degree of sensitivity to CK2 inhibition could mirror differences in clinical or biologic parameters with prognostic value. We did not find a consistent correlation between the proapoptotic effect of TBB or DRB and lymphocyte doubling time, ZAP-70 and CD38 expression, or IGHV mutational status (data not shown). In contrast, there was a significant correlation between the percentage of malignant cells in the peripheral blood of CLL patients and sensitivity to TBB (P = .0013; Figure 6A) or DRB (P = .0013; Figure 6B). In addition, CLL cells from patients with low disease burden (Binet stage A) were less susceptible to CK2 inhibition than patients with advanced disease (Binet stage B or C) when treated with TBB (P = .0008; Figure 6C) or DRB (P = .0160; data not shown). We further analyzed serum β2 microglobulin, which is associated with tumor burden and bone marrow infiltration, and inversely correlates with response to chemotherapy and overall survival.39 CLL cells from patients with higher β2 microglobulin had lower viability upon culture with TBB (Figure 6D and supplemental Figure 3). DRB treatment showed the same tendency although not reaching statistical significance (data not shown). Altogether, our data indicate that CLL cells from patients with evidence of more advanced disease (higher percentage of malignant cells in the peripheral blood, higher β2 microglobulin levels or Binet stage B/C) display higher sensitivity to CK2 inhibition.

Sensitivity of primary CLL cells to CK2 inhibition correlates with percentage of leukemia cells in the peripheral blood, clinical stage and β2 microglobulin levels. Correlation between percentage of CLL cells in the peripheral blood and viability index of purified CLL cells cultured with (A) 25μM TBB (n = 19) or (B) 25μM DRB (n = 14) for 48 hours. (C) Clinical stage A (n = 12) or stage B and C (n = 6) CLL patients. CLL viability after culture with 25μM TBB for 48 hours. Results are shown as mean ± SEM. (D) CLL patients with < 3 mg/L (n = 7) or > 3 mg/L (n = 9) β2 microglobulin. CLL viability after culture with 25μM TBB for 48 hours. Results are shown as mean ± SEM.

Sensitivity of primary CLL cells to CK2 inhibition correlates with percentage of leukemia cells in the peripheral blood, clinical stage and β2 microglobulin levels. Correlation between percentage of CLL cells in the peripheral blood and viability index of purified CLL cells cultured with (A) 25μM TBB (n = 19) or (B) 25μM DRB (n = 14) for 48 hours. (C) Clinical stage A (n = 12) or stage B and C (n = 6) CLL patients. CLL viability after culture with 25μM TBB for 48 hours. Results are shown as mean ± SEM. (D) CLL patients with < 3 mg/L (n = 7) or > 3 mg/L (n = 9) β2 microglobulin. CLL viability after culture with 25μM TBB for 48 hours. Results are shown as mean ± SEM.

Discussion

CLL remains an incurable cancer.40 Our present data indicate that CK2 is an important regulator of CLL cell viability and identify CK2 as a potential target for therapeutic intervention in this malignancy. We demonstrated that CK2 is overexpressed and hyperactivated in CLL cells compared with normal B cells from age-matched healthy donors. As for other cancers, the mechanisms responsible for CK2 deregulation in CLL remain unsettled and deserve further investigation. In addition, defining exactly how CK2 activity integrates the network of signals that promote CLL cell survival will be of particular relevance. In the present study, we found that CK2 negatively modulates PTEN activity in CLL, and promotes leukemia cell viability, at least in part, by up-regulating PKC phosphorylation/activation.

Most CLL cells aberrantly express CD5 on their surface.1 Interestingly, it has been shown that CK2β physically interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of CD5 in lymphocytes and triggering of CD5 can induce the activation of CD5-associated CK2.41 Whether a relevant functional link may exist between CD5 and CK2 activity in CLL remains to be evaluated. However, we did not find a correlation between CD5 expression and sensitivity to CK2 inhibition in the primary CLL samples we analyzed (eg, n = 11, P = .7284 for TBB 25μM).

Akt/PKB is the major downstream effector of PI3K signaling, which is counteracted by PTEN. Because CK2 was overexpressed in most CLL patients, we were surprised to realize that Akt phosphorylation was generally similar to that found in healthy controls. Despite the extensive evidence implicating PI3K-dependent signaling in CLL cell survival, the exact role and levels of basal activation of Akt in CLL remain controversial.16-18,42-45 Discrepancies may relate to differences among patient populations used in distinct analyses, technical issues and/or to the fact that not all studies compared patient samples with age-matched healthy controls. Interestingly, we found that CK2 inhibition decreased Akt phosphorylation in the few patients who displayed high levels of Akt constitutive activation (data not shown), suggesting that in some CLL patients a CK2-PTEN-PI3K-Akt axis may exist similar to that described for T-cell leukemia.24

In contrast to Akt, we found that PKCβ and -δ are hyperphosphorylayed in the majority of primary CLL cells we analyzed. Our data suggest that PI3K pathway may be shifted toward preferential activation of PKC in CLL, and are in agreement with previous studies showing that PKCδ, but not Akt, is constitutively activated in a PI3K-dependent manner in primary CLL cells.35 Furthermore, inhibition of PKCδ or PKCβ, which is essential to the development of CLL in mice, induces apoptosis of CLL cells.35-37 Our current studies indicate that PKC hyperactivation is positively regulated by CK2, possibly as a result of PI3K signaling pathway activation driven by CK2-mediated PTEN posttranslational blockade.14,19,46 In turn, PKC activation appears to be critical for CK2-mediated viability in CLL cells, since PMA is sufficient to reverse the proapoptotic effects of CK2 inhibition.

Importantly, all patient samples and CLL cell lines tested in our studies were sensitive to CK2 inhibition and entered apoptosis upon treatment with the CK2-specific pharmacologic inhibitors TBB, DRB and CX-4945, or upon CK2α knockdown. In contrast, normal B and T lymphocytes collected from healthy controls were not significantly affected. Interestingly, the finding that T cells from CLL patients were mildly sensitive to CK2 inhibition may underscore the interplay between leukemia B cells and leukemia-recruited T cells29,47,48 and possibly suggest that the T cells that interact with the malignant cells and thereby partake in leukemia development may also be eliminated, perhaps due to crosstalk interruption, by small molecule inhibitors of CK2. Irrespective of these considerations, our data indicate that CK2 can be targeted to selectively eliminate the malignant B cells without impacting normal lymphoid cells.

There is strong evidence implicating the microenvironment in the development and maintenance of CLL.40,47,49,50 Moreover, extracellular cues may also promote CLL cell resistance to chemotherapy.51 Our studies showed that the proapoptotic effect of CK2 inhibitors on CLL cells was not reversed by coculture with a stromal cell line that could otherwise up-regulate the viability of CLL cells. This indicates that blockade of CK2 activity is sufficient to trigger leukemia cell death even in the presence of pro-survival signals from the microenvironment, strengthening the potential clinical relevance of the use of CK2 inhibitors in CLL.

CLL cells from patients with clinical evidence of advanced disease (Binet stage B/C, high percentage of malignant cells in the peripheral blood, and high levels of serum β2 microglobulin) showed increased sensitivity to CK2 pharmacologic inhibition. These observations suggest that particular patient subsets may especially benefit from targeting CK2 function. Whether they reveal increased dependence (“non-oncogene addiction”) on CK2 as disease progresses or whether, alternatively, CK2 may serve as an independent prognostic marker, remains to be determined. Interestingly, no relationship was observed between CK2-dependent survival and expression of CD38, a poor prognosis marker that has been related with the proliferative capacity of the tumor cells.49 Other conventional prognostic markers, namely ZAP-70 expression, IGHV mutational status and cytogenetics, could not be consistently related to sensitivity to CK2 inhibitors. Although this may be due to a small sample size, it may alternatively reflect the ability of CK2 antagonizing drugs to affect biologically different disease subsets. Indeed, to a greater or lesser extent, CK2 inhibition was clearly effective in inducing significant apoptosis in all patient samples analyzed, independently of clinical and biologic status.

Overall, our studies identify CK2 as a critical regulator of CLL cell viability, acting at least in part via regulation of PTEN and PKC. The efficacy of CK2 inhibitors in selectively eliminating CLL cells, even in the presence of stromal support, suggests that strategies targeting CK2 function may have broad therapeutic value in CLL.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the patients and healthy donors that made this study possible. We thank Dr Paolo Ghia for kindly providing JVM-3 and MEC1 cell lines.

This work was supported by the grant PIC/IC/83 193/2007 from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia. L.R.M. has an FCT-SFRH PhD fellowship.

Authorship

Contribution: L.R.M. designed research, performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; M.C.S. performed experiments and analyzed data; P.G. performed IGVH mutational status analysis; K.L.A. provided critical reagents; P.L. and M.G.S. collected, analyzed and interpreted clinical data, and contributed with experimental suggestions; M.G.S. critically read the manuscript; and J.T.B. designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, wrote the manuscript and coordinated the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.L.A. is an employee of Cylene Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Correspondence: João T. Barata, Cancer Biology Unit, Instituto de Medicina Molecular, Lisbon University Medical School, Av Prof Egas Moniz, 1649-028 Lisboa, Portugal; e-mail: joao_barata@fm.ul.pt.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal