Abstract

For older patients with early unfavorable or advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) the prognosis is much worse than for younger HL patients. We thus developed a new regimen, BACOPP (bleomycin, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone), to improve both tolerability and efficacy of treatment for older HL patients. Between 2004 and 2005, 65 patients with early unfavorable or advanced stage HL aged between 60 and 75 years were enrolled in this phase 2 trial. Treatment consisted of 6 to 8 cycles of BACOPP. Residual tumor masses were irradiated. Primary endpoints were feasibility as determined by adherence to protocol and overall response rate. Secondary endpoints included toxicity, freedom from treatment failure, and progression free and overall survival. For the final analysis 60 patients (92%) were eligible; 75% of treatment courses were administered according to protocol. World Health Organization grade 3/4 toxicities occurred in 52 patients. Fifty-one patients (85%) achieved complete remission, 2 (3%) partial remission, and 4 (7%) developed progressive disease. With a median observation time of 33 months, 18 patients died (30%), including 7 treatment-associated deaths. Three patients died before response assessment. Thus, the BACOPP regimen is active in older HL patients but is compromised by a high rate of toxic deaths. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00284271.

Introduction

During the past 3 decades the prognosis for patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) has substantially improved. This success is mainly based on the introduction of effective combination chemotherapy regimens, progress in radiation techniques, and constant optimization of treatment methods. Even in patients with advanced stages, long-term failure-free survival (FFS) of 82% to 89% can be achieved by intensified treatment such as bleomycin, etoposide, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine (Oncovin), procarbazine, and prednisone (BEACOPP) escalated or other multiagent regimens.1-3

Unfortunately, these improvements have not been extended to older patients despite some better understanding of the pathophysiology.4 Approximately 20% of patients with HL are older than 60 years of age5 and face a poorer prognosis especially when presenting with advanced stages.6-14 Age is a strong negative predictor for survival.15 Additional factors contribute to the unsatisfactory outcome in older patients such as more aggressive biology,6,16 comorbidities,17 reduced tolerance of treatment, failure to maintain dose intensity, more treatment-related deaths, as well as shorter survival after relapse.6,7,12,13,18,19 In contrast to younger patients treatment standards are lacking because there are only a few studies for this cohort of patients. The first prospective randomized trial in this setting was HD9elderly19 conducted by our group in which COPP/adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) was compared with BEACOPP baseline. In this trial, patients aged between 65 and 75 years did not benefit from BEACOPP baseline in terms of overall survival (OS), although a better HL-specific freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) was achieved.19 As a direct consequence the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) developed the BACOPP regimen that consisted of bleomycin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone. Compared with BEACOPP baseline, etoposide was omitted, and the anthracycline dose was increased. Anthracyclines might be one of the most relevant components of chemotherapy in older patients.20 The aim of the present study was to investigate feasibility and efficacy of this modified regimen in older patients with HL.

Methods

Patients

Between January 2004 and December 2005, patients with newly diagnosed histology-proven HL in clinical stages I and II with at least 1 risk factor as well as clinical stages III and IV were enrolled into the trial. Risk factors included large mediastinal mass (at least one-third of the maximal thorax diameter), extranodal disease, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (≥ 50 mm/h in patients without B symptoms; ≥ 30mm/h in patients with B symptoms) and 3 or more lymph node areas involved. Patients had to be between 60 and 75 years, to have normal organ function and good general condition (World Health Organization [WHO] Index ≤ 2). Patients with impaired heart, lung, liver, or kidney function; deficiency of vitamin B12 or folic acid; hemolysis; previous malignant disease; positive HIV status; or hepatitis B infection were not included. Minimal hematologic requirements included a white blood cell count greater than 3000/μL and platelet count greater than 100 000/μL. Biopsy material was judged by the local pathologist and then reviewed by at least 1 member of the central pathology review panel consisting of 6 German HL experts. Composite lymphomas were excluded. Staging and pretreatment evaluation contained medical history; physical examination; chest radiography; computed tomography of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis; ultrasound scans of the neck and the abdomen; bone marrow biopsy; skeletal scintigraphy; serum chemistry; lung function test; electrocardiography; and echocardiography. Written informed consent was signed by each patient before enrollment. The study was approved by the University Hospital of Cologne Ethic Committee, conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00284271. A routine safety monitoring was conducted throughout the whole study.

Study design and chemotherapy

In this prospective phase 2 trial pretreatment with 1 mg of vincristine on day −6 and 100 mg of prednisone from day −6 to day 0 was mandatory. All cytotoxic drugs were given within 8 days and recycled after 21 days. For patients older than 65 years the vincristine dose was restricted to 1 mg. The regimen is shown in Table 1. Patients achieving a complete remission (CR) after 4 cycles of BACOPP received 2 additional cycles of treatment, whereas patients with a partial remission (PR) were to receive 4 additional cycles.

Drug doses and schedules

| . | Dose . | Route . | Day . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment (1 wk) | |||

| Vincristine | 1 mg | IV | −6 |

| Prednisone | 100 mg | PO | −6-0 |

| BACOPP (recycle day 22) | |||

| Cyclophosphamide | 650 mg/m2 | IV | 1 |

| Adriamycin | 50 mg/m2 | IV | 1 |

| Procarbazine | 100 mg/m2 | PO | 1-7 |

| Prednisone | 40 mg/m2 | PO | 1-14 |

| Bleomycin | 10 mg/m2 | IV | 8 |

| Vincristine | 1.4 mg/m2* | IV | 8 |

| . | Dose . | Route . | Day . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment (1 wk) | |||

| Vincristine | 1 mg | IV | −6 |

| Prednisone | 100 mg | PO | −6-0 |

| BACOPP (recycle day 22) | |||

| Cyclophosphamide | 650 mg/m2 | IV | 1 |

| Adriamycin | 50 mg/m2 | IV | 1 |

| Procarbazine | 100 mg/m2 | PO | 1-7 |

| Prednisone | 40 mg/m2 | PO | 1-14 |

| Bleomycin | 10 mg/m2 | IV | 8 |

| Vincristine | 1.4 mg/m2* | IV | 8 |

BACOPP indicates bleomycin, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; IV, intravenous; and PO, per os.

Patients younger than 65 years receive a maximum of 2 mg; patients older than 65 years receive a maximum of 1 mg.

Depending on hemoglobin values the concomitant application of erythropoietin-β was mandatory throughout chemotherapy. The subcutaneous application of 30 000 IE erythropoietin-β was started during the first week of chemotherapy if the hemoglobin value was less than 14 g/dL and repeated weekly until the hemoglobin value exceeded 14 g/dL. The administration was interrupted until the hemoglobin value had fallen to less than 12 g/dL. At values below 12 g/dL the application of erythropoietin-β was continued. Patients with decline of more than 2 g/dL or more than 6 weeks without any other medical explanation or the need of erythrocyte transfusion were considered as nonresponders. Nonresponders received 30 000 IE of erythropoietin-β 2 times per week. After the end of chemotherapy erythropoietin-β could be administered for up to 6 weeks if the hemoglobin value was below 12 g/dL with a dose of 30 000 IE per week until exceeding 12 g/dL.

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) was given according to guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).21

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy was only administered in patients with PR after 8 cycles of BACOPP having a residual mass of 2.5 cm or more. Radiation fields were restricted to the residual mass and irradiated with 30 Gy. Radiotherapy was also used to treat osteolytic bone lesions.

Assessment of response and toxicity

A restaging was mandatory after 4 cycles of BACOPP and included computed tomographic scans of involved sites. All toxicities determined under therapy and during follow-up had to be documented according to the WHO toxicity criteria. The final restaging was performed in the last week of chemotherapy or in the case of additional radiotherapy 4 to 6 weeks after the end of irradiation and included assessment of initial involved sites. CR was defined as disappearance of all clinical and radiologic disease; PR was defined as reduction of at least 50% of maximal diameter compared with the initial involvement. Residual disease after chemotherapy and radiotherapy was considered as CRu (CR uncertain with residual lesion) when no additional treatment was required.19

Statistical methods

Feasibility was measured according to protocol adherence. The cutoff values used for the definition of protocol deviations were greater than 25% deviation from planned total dose and/or greater than 50% deviation from recommended dose of a single drug. The regimen was considered feasible if 65% or greater of patients were treated without protocol deviations. A vincristine dose of 2 mg in patients older than 65 years was no protocol deviation. Response was determined according to the criteria described in “Assessment of response and toxicity.”19 Toxicity was registered in accordance with the WHO toxicity criteria and analyzed for WHO grade 3 and 4 toxicity. Progression free survival (PFS), FFTF, and OS were estimated according to the method of Kaplan-Meier.22

Results

Patient characteristics

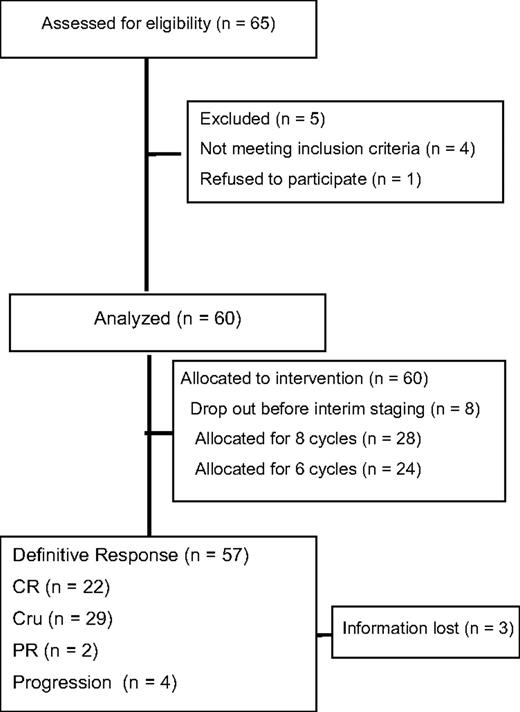

Between January 2004 and December 2005, a total of 65 patients were registered. Five patients had to be excluded, 2 with no HL and 1 each for wrong staging, previous treatment, or withdrawn consent. Thus, 60 patients were eligible for the final analysis (Figure 1). Median age was 66.7 years. There were slightly more men included in this trial (57% vs 43%). Histology showed a predominance of the mixed cellularity subtype (29 patients; 48%) followed by nodular sclerosis (17 patients; 28%). Of the enrolled patients, 67% presented with advanced stages, 33% were in early unfavorable stages (Table 2). The International Prognostic Score (IPS)15 was 0 to 1 for 13%, 2 to 3 for 58%, and 4 to 7 for 29% of patients, respectively.

Patient characteristics

| . | No. . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||

| 60-64 | 22 | 37 |

| 65-69 | 25 | 42 |

| 70-75 | 13 | 22 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 26 | 43 |

| Male | 34 | 57 |

| Histology | ||

| Lymphocyte predominant | 4 | 7 |

| Nodular sclerosis | 17 | 28 |

| Mixed cellularity | 29 | 48 |

| Classical HL, unspecified | 10 | 17 |

| Stage | ||

| IA | 1 | 2 |

| IB | 1 | 2 |

| IIA | 11 | 18 |

| IIB | 10 | 17 |

| IIIA | 8 | 13 |

| IIIB | 5 | 8 |

| IVA | 6 | 10 |

| IVB | 18 | 30 |

| Early unfavorable | 20 | 33 |

| Advanced | 40 | 67 |

| Risk factor | ||

| Large mediastinal mass | 3 | 5 |

| Extranodal involvement | 11 | 19 |

| 3 or more lymph node areas | 42 | 71 |

| Elevated ESR | 39 | 68 |

| . | No. . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||

| 60-64 | 22 | 37 |

| 65-69 | 25 | 42 |

| 70-75 | 13 | 22 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 26 | 43 |

| Male | 34 | 57 |

| Histology | ||

| Lymphocyte predominant | 4 | 7 |

| Nodular sclerosis | 17 | 28 |

| Mixed cellularity | 29 | 48 |

| Classical HL, unspecified | 10 | 17 |

| Stage | ||

| IA | 1 | 2 |

| IB | 1 | 2 |

| IIA | 11 | 18 |

| IIB | 10 | 17 |

| IIIA | 8 | 13 |

| IIIB | 5 | 8 |

| IVA | 6 | 10 |

| IVB | 18 | 30 |

| Early unfavorable | 20 | 33 |

| Advanced | 40 | 67 |

| Risk factor | ||

| Large mediastinal mass | 3 | 5 |

| Extranodal involvement | 11 | 19 |

| 3 or more lymph node areas | 42 | 71 |

| Elevated ESR | 39 | 68 |

HL indicates Hodgkin lymphoma; and ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Administration of therapy

Of 60 patients, 45 received their treatment according to protocol. In total, 75% (95% CI: 62%-85%) of treatment courses were administered on schedule. Early termination was documented in 18 patients (30%), in 17 during the first 4 cycles of chemotherapy, and in 1 patient after the interim staging. Reasons for early termination were extensive toxicity (9 patients), concomitant disease (4 patients), patients wish (2 patients), progression (1 patient), and others (2 patients). Two patients received 8 cycles of BACOPP instead of 6 cycles. Radiotherapy according to protocol was performed in 8 patients.

Use of G-CSF

G-CSF was used in 37% of patients, 38% treated with 6 cycles of BACOPP and 36% treated with 8 cycles of BACOPP. During the first cycle of BACOPP no G-CSF was applied. For cycles 2 to 6 the number of days with G-CSF ranged between 1 day and 14 days (mean: 4.6 days). In cycle 7 and 8 the mean was 5.7 days (range: 1-14 days) and 5.3 days (range: 1-7 days), respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of severe infections or sepsis between patients receiving G-CSF and those who never were treated with G-CSF.

Response to erythropoietin-β

In total, 55% of patients were nonresponders to erythropoietin-β with necessity of erythrocyte transfusion in 23% of patients. According to treatment arm, 14 patients treated with 6 cycles of BACOPP were nonresponders with a red blood cell transfusion given in 7 patients. In the group of patients who received 8 cycles of BACOPP, 15 patients were classified as nonresponders with a need of red blood cell transfusions in 5 patients. No thromboses or thromboembolic events have been registered throughout the study and follow-up period.

Toxicity

WHO grade 3 and 4 toxicities were documented in 52 patients (87%). The main toxicities were leucopenia (70%), infection (23%), and thrombopenia (22%). Deaths from acute toxicity occurred in 7 patients (2 women and 5 men) because of severe infection after 1.2 to 5.7 months after registration (Table 3). The subgroup analysis showed no association between the development of toxicity and IPS or stage.

Toxicity WHO grade 3/4

| . | BACOPP . | HD9elderly . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO grade, no. of patients . | WHO grade 3/4, % . | WHO grade 3/4, % . | |||

| III . | IV . | COPP/ABVD . | BEACOPP baseline . | ||

| Anemia | 9 | 1 | 17 | 24 | 41 |

| Thrombopenia | 2 | 11 | 22 | 16 | 49 |

| Leucopenia | 10 | 32 | 70 | 84 | 92 |

| Infection | 12 | 2 | 23 | 12 | 23 |

| Nausea | 5 | 8 | 12 | 18 | |

| Mucositis | 7 | 12 | 13 | ||

| Gastrointestinal tract | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | |

| Respiratory | 4 | 3 | 12 | 8 | |

| Cardiac | 4 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 15 |

| Neurotoxicity | 6 | 1 | 12 | 12 | 13 |

| . | BACOPP . | HD9elderly . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO grade, no. of patients . | WHO grade 3/4, % . | WHO grade 3/4, % . | |||

| III . | IV . | COPP/ABVD . | BEACOPP baseline . | ||

| Anemia | 9 | 1 | 17 | 24 | 41 |

| Thrombopenia | 2 | 11 | 22 | 16 | 49 |

| Leucopenia | 10 | 32 | 70 | 84 | 92 |

| Infection | 12 | 2 | 23 | 12 | 23 |

| Nausea | 5 | 8 | 12 | 18 | |

| Mucositis | 7 | 12 | 13 | ||

| Gastrointestinal tract | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | |

| Respiratory | 4 | 3 | 12 | 8 | |

| Cardiac | 4 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 15 |

| Neurotoxicity | 6 | 1 | 12 | 12 | 13 |

WHO indicates World Health Organization; BACOPP, bleomycin, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; HD9elderly, German Hodgkin Study Group trial; COPP/ABVD, cyclophosphamide, vincristine (Oncovin), procarbazine, and prednisone/adriamycin, bleomycin, vincristine, and dacarbazine; and BEACOPP, bleomycin, etoposide, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine (Oncovin), procarbazine, and prednisone.

Disease control and survival

Complete responses (CR and CRu) were achieved in 85% of all patients. Three percent had a PR and 7% had disease progression. Five percent died before restaging with unknown response (Table 4). With a median observation time of 33 months, a total of 8 relapses and 5 second malignancies (3 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), 2 with lung cancer) were observed.

Treatment outcome

| . | No. of patients . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Complete response | 51 | 85 |

| CR | 22 | 37 |

| CRu | 29 | 48 |

| Partial remission | 2 | 3 |

| Progression | 4 | 7 |

| Unknown (death) | 3 | 5 |

| Relapse | 8 | 13 |

| Second malignancy | 5 | 8 |

| . | No. of patients . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Complete response | 51 | 85 |

| CR | 22 | 37 |

| CRu | 29 | 48 |

| Partial remission | 2 | 3 |

| Progression | 4 | 7 |

| Unknown (death) | 3 | 5 |

| Relapse | 8 | 13 |

| Second malignancy | 5 | 8 |

CR indicates complete remission; and CRu, complete remission uncertain with residual lesion.

In the follow-up, 6 patients died of relapsing or progressing HL, 2 of second malignancies (1 of lung cancer after 44 months and 1 of secondary B-cell NHL after 17 months) and 3 patients as a result of other reasons. The causes of death are listed in Table 5.

Causes of death

| . | BACOPP . | HD9 elderly . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients . | % . | COPP/ABVD, % . | BEACOPP baseline, % . | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 6 | 10 | 23 | 17 |

| Acute toxicity | 7 | 12 | 8 | 21 |

| Second malignancy | 2 | 3 | 8 | 10 |

| Other | 3 | 5 | 15 | 7 |

| Total deaths | 18 | 30 | 54 | 55 |

| Median observation time, mo | 33 | 100 | 100 | |

| . | BACOPP . | HD9 elderly . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients . | % . | COPP/ABVD, % . | BEACOPP baseline, % . | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 6 | 10 | 23 | 17 |

| Acute toxicity | 7 | 12 | 8 | 21 |

| Second malignancy | 2 | 3 | 8 | 10 |

| Other | 3 | 5 | 15 | 7 |

| Total deaths | 18 | 30 | 54 | 55 |

| Median observation time, mo | 33 | 100 | 100 | |

BACOPP indicates bleomycin, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; HD9elderly, German Hodgkin Study Group trial; COPP/ABVD, cyclophosphamide, vincristine (Oncovin), procarbazine, and prednisone/adriamycin, bleomycin, vincristine, and dacarbazine; and BEACOPP, bleomycin, etoposide, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine (Oncovin), procarbazine, and prednisone.

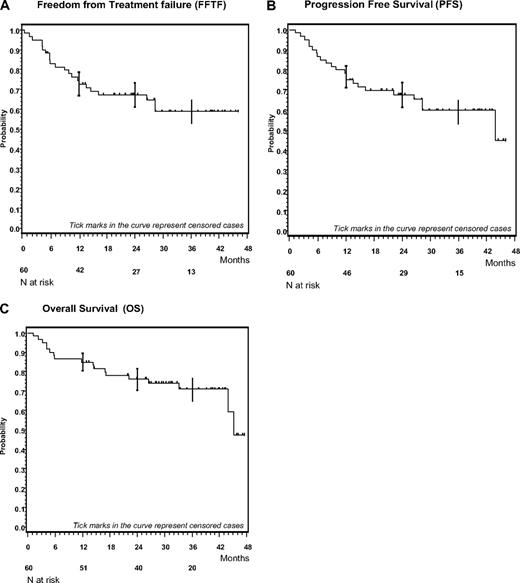

Overall 18 patients (30%) have died so far. The Kaplan-Meier plots for OS, FFTF, and PFS are shown in Figure 2. The FFTF, PFS, and OS rates for all patients at 3 years were 59% (95% CI: 45%-73%), 60% (95% CI: 46%-73%), and 71% (95% CI: 59%-83%), respectively. For patients in advanced stages the FFTF, PFS, and OS rates at 3 years were 61% (95% CI: 42%-75%), 62% (95% CI: 44%-76%), and 66% (95% CI: 47%-80%), respectively.

Kaplan-Meier plots of BACOPP. (A) Kaplan-Meier analysis of freedom from treatment failure (FFTF). (B) Kaplan-Meier analysis of progression free survival (PFS). (C) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (OS).

Kaplan-Meier plots of BACOPP. (A) Kaplan-Meier analysis of freedom from treatment failure (FFTF). (B) Kaplan-Meier analysis of progression free survival (PFS). (C) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (OS).

Management of progress or relapse

Primary progressive disease was observed in 4 patients. Early termination of therapy because of toxicity became necessary in 1 patient with progressive disease. The other 3 patients died within 6.6 to 33 months after progressing. All 3 patients had received salvage chemotherapy. In 1 case additional radiation was given.

Relapse after the end of therapy was documented in 8 patients occurring 8 to 28 months after registration. Three patients died within 5 months after diagnosis of relapse, 1 because of second malignancy. Salvage chemotherapy was given in 2 of these patients. Five patients alive at the time of this analysis received salvage radiotherapy (2 patients) or salvage chemotherapy (2 patients); 1 patient refused salvage therapy.

A complete remission was achieved only in 1 patient treated with salvage radiation. The other patients progressed or relapsed after salvage therapy. All these patients were under treatment at the time of the present analysis.

Discussion

The primary objective of this phase 2 trial was feasibility and efficacy of the newly developed BACOPP regimen for older patients with HL in early unfavorable and advanced stages. The following findings emerge from this study. (1) BACOPP is active with 85% of patients with HL aged 60 to 75 years achieving CR. FFTF, PFS, and OS at 3 years were 59%, 60%, and 71%, respectively. This response is among the best reported so far in older patients with HL.20,23-25 (2) However, the good efficacy of BACOPP was compromised by 12% treatment-associated mortality. (3) Patients who relapsed or had progressive disease after BACOPP showed a poor response to salvage treatment.

Older patients with HL generally have a poorer prognosis than patients younger than 60 years. A recent GHSG analysis showed a 5-year OS of 65% for older patients compared with 90% in younger patients. The 5-year FFTF was 60% and 80% and HL-specific FFTF was 73% and 82%, respectively.26 These findings are in line with other studies in older patients with HL reporting 5-year OS that ranged from 30% to 67%.16,20,23,27 The GHSG HD9elderly trial19 was the first prospective randomized trial in this patient population. In this study, COPP/ABVD was compared with BEACOPP in baseline dose. Even though BEACOPP showed good HL-specific FFTF (74% vs 55%), the better tumor control did not translate into improved outcome; the OS at 5 years was 50% for both regimens. This was mainly due to 21% toxic deaths after BEACOPP compared with 8% after COPP/ABVD.19 Severe hematologic toxicity is the main reason for treatment-related death in older patients with HL12,19,20,28 and even if not fatal might lead to lower overall intensity of treatment.26,29

In the present trial, 45 patients received at least 75% of the planned total dose and showed no more than 50% deviation from the recommended dose of a single drug. Of all treatment courses, 75% were administered according to protocol. As demonstrated by Landgren et al,29 a relative dose intensity of more than 65% was associated with a better cancer-specific survival (P = .024) and OS (P = .029) in older patients with HL. Levis et al12 reported a relative dose intensity of only 47% for patients older than 65 years receiving 6 cycles of ABVD-based chemotherapy. CR rates published for older patients with HL range between 49% and 77% for mechlorethamine (Mustargen), vincristine (Oncovin), procarbazine, prednisone (MOPP), MOPP/ABVD, BEACOPP baseline, and COPP/ABVD-like regimens.12,19,29,30 Thus, the CR rate for BACOPP of 85% compares favorably with other regimens reported. The outcome was not associated with stage or IPS, although these results might be humbled by the small sample size.

In the present study 70% of patients had severe leucopenia and 23% severe infections (Table 3). There was also no association of these events with stage or IPS.

The rate of toxic deaths (12%) observed with BACOPP is too high but within the range reported for regimens such as MOPP or ABVD variants when used in older patients with HL.13,18,19,27,30 Today, ABVD has replaced most of these regimens and is being regarded as standard of care. This is in part based on the work of Canellos et al31 who demonstrated a similar efficacy and lower myelotoxicity for ABVD than for MOPP or MOPP/ABVD. Information on toxic deaths after ABVD are however scarce, particularly in older patients.24,31,32 In the study conducted by Canellos et al,31 only 7 patients in the ABVD arm were older than 60 years. Of those patients, 2 died of toxicity. In contrast Levis et al24 reported no toxic death caused by ABVD in older patients with HL in a preliminary analysis.

G-CSF has been suggested to reduce the incidence of severe neutropenia and toxic death in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.12,33,34 However, a randomized trial conducted in older patients with NHL comparing cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) with CHOP plus G-CSF showed no prevention of serious infections or mortality.35 These results were in line with a systemic review that investigated the effect of G-CSF on outcome in patients with lymphoma.36 In our analysis there was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of severe infections or sepsis for patients receiving G-CSF and those who were never treated with G-CSF. It thus remains to be shown if the routine use of G-CSF improves the survival in older patients with HL undergoing chemotherapy.37

Studies conducted by an Italian Group evaluating the less toxic regimen of chlorambucil, vinblastine, procarbazine, prednisone/cyclophosphamide, etoposide, and bleomycin reported a CR rate of 73% with 4% treatment-related deaths. Unfortunately, the effect of this regimen was offset by a high relapse rate with an event-free survival of 30%.27 Vinblastine, cyclophosphamide, procarbazine, prednisone, etoposide, mitoxantrone, and bleomycin is another interesting regimen reported for use in older patients with HL. The pilot study raised expectations that it might be both effective and well tolerated.23 The first results of a prospective randomized trial that compared vinblastine, cyclophosphamide, procarbazine, prednisone, etoposide, mitoxantrone, and bleomycin with ABVD were presented.24 CR rates, 3-year OS, and event-free survival were better in the ABVD arm (86% vs 77%, 79% vs 60%, and 52% vs 24%, respectively), although these differences were not significant.24 Kolstad et al25 used CHOP to treat 11 older patients with HL with early-stage HL and 18 patients with advanced-stage HL. The CR rate was 93% for the whole group. With a median follow-up of 41 months, OS and PFS at 3 years were 79% and 76%. When patients in early and advanced stages were compared, the OS at 3 years was 91% and 67% with a PFS at 3 years of 82% and 72%, respectively.25 Two patients died of acute toxicity. However, the patient numbers are too small for further conclusions.

In older patients with HL, historical comparison of efficacy and tolerability between trials are generally more difficult because of the small patient numbers and different patient characteristics. Patients included in the prior randomized GHSG HD9elderly study were older than those in the present trial (median age of 69.5 vs 66.7 years). In addition, there were more patients in stages III and IV (89% or 100% in HD9elderly vs 62% in the current study). However, Kaplan-Meier estimates for PFS and OS in BACOPP were not different if the cohort was restricted to advanced-stage patients only. Not withstanding these caveats, severe leucopenia and toxic deaths were lower in the current trial (70% and 12%) than in the BEACOPP baseline arm of HD9elderly (92% and 21%).19 Although this might suggest a better tolerability of BACOPP in older patients with HL, treatment-related mortality of this regimen is not acceptable so that this regimen should only be used within clinical trials.

A comparison of BACOPP as presented here with ABVD is more difficult because of the scarce data on ABVD-related toxic deaths when used in patients 60 years or older. Although an evidence-based standard is lacking for older patients with HL, most groups regard 4 cycles of ABVD in early unfavorable and 6 to 8 cycles of ABVD in advanced stages as standard of care. This is often followed by involved field radiotherapy of 30 Gy for early unfavorable and radiation to residual disease for advanced-stage patients. It is generally accepted that antitumor activity and tolerability of ABVD in this patient cohort needs further improvement. Because chemotherapy intensification has major limitations in older patients with HL as also seen in the present study, we urgently need new approaches that include nongenotoxic drugs to be evaluated in older patients with HL. The GHSG has therefore initiated a phase 1/2 trial combining AVD plus lenalidomide in this patient cohort. In addition, new trials should also incorporate special geriatric assessments that might help to improve the estimate of frailty.

In conclusion, the newly developed BACOPP regimen showed good antitumor activity in older patients with HL but was associated with 12% treatment-related mortality. Although this is within the range of other regimens used, we do not recommend BACOPP outside clinical trails in this patient population.

Presented in part at the 50th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, December 7, 2008.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the contributing centers. The erythropoietin-β used in this trial was supplied by Roche.

Authorship

Contribution: L.N., V.D., A.E., and A.J. provided conception and design; A.J. and A.E. provided financial support; T.V.H., L.N., M.S., D.A.E., T.S., and A.J. provided administrative support; L.N., M.S., and A.J. provided study materials or patients; T.V.H., L.N., H.M., M.S., D.A.E., H.N.-B., and A.J. collected and assembled data; T.V.H., H.M., and A.J. analyzed data; T.V.H., P.B., A.J., and A.E. wrote the manuscript; and T.V.H., L.N., H.M., M.S., D.A.E., T.S., H.N.-B., P.B., V.D., A.E., and A.J. provided final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

For a complete list of the members of the German Hodgkin Study Group, see the supplemental Appendix (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Correspondence: Andreas Engert, First Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital of Cologne, 50924 Cologne, Germany; e-mail: a.engert@uni-koeln.de.

References

Author notes

T.V.H. and L.N. contributed equally to this study.