Abstract

Systemic mastocytosis (SM) is a myeloid neoplasm involving mast cells (MCs) and their progenitors. In most cases, neoplastic cells display the D816V-mutated variant of KIT. KIT D816V exhibits constitutive tyrosine kinase (TK) activity and has been implicated in increased survival and growth of neoplastic MCs. Recent data suggest that the proapoptotic BH3-only death regulator Bim plays a role as a tumor suppressor in various myeloid neoplasms. We found that KIT D816V suppresses expression of Bim in Ba/F3 cells. The KIT D816–induced down-regulation of Bim was rescued by the KIT-targeting drug PKC412/midostaurin. Both PKC412 and the proteasome-inhibitor bortezomib were found to decrease growth and promote expression of Bim in MC leukemia cell lines HMC-1.1 (D816V negative) and HMC-1.2 (D816V positive). Both drugs were also found to counteract growth of primary neoplastic MCs. Furthermore, midostaurin was found to cooperate with bortezomib and with the BH3-mimetic obatoclax in producing growth inhibition in both HMC-1 subclones. Finally, a Bim-specific siRNA was found to rescue HMC-1 cells from PKC412-induced cell death. Our data show that KIT D816V suppresses expression of proapoptotic Bim in neoplastic MCs. Targeting of Bcl-2 family members by drugs promoting Bim (re)-expression, or by BH3-mimetics such as obatoclax, may be an attractive therapy concept in SM.

Introduction

Mastocytosis is a term collectively used for disorders characterized by abnormal growth and accumulation of tissue mast cells (MCs) in one or more organ systems.1-5 Cutaneous as well as systemic variants of the disease have been described.1-5 Systemic mastocytosis (SM) represents a persistent clonal disorder of MCs characterized by the involvement of one or more visceral organs with or without skin involvement.3-5 In a majority of all patients, the transforming KIT mutation D816V is detectable.6-12 This mutant is expressed in MCs as well as in MC progenitors in most cases, and is considered to play a predominant role for survival and growth of malignant cells in SM.6-13 Therefore, KIT D816V has been recognized as a potential target of therapy in SM.14-18 Notably, several efforts have recently been undertaken to identify new tyrosine kinase (TK) inhibitors that counteract phosphorylation of KIT D816V and thus the growth of neoplastic MCs.14-20 Indeed, several of the new TK inhibitors have been described to counteract malignant cell growth in patients with aggressive SM (ASM) or mast cell leukemia (MCL).17-23 These inhibitors include midostaurin (PKC412), nilotinib (AMN107), and dasatinib.17-23 However, the first clinical data suggest that long-lasting responses cannot be achieved in all patients with such inhibitors, at least when applied as single drugs.18

Therefore, several attempts have been made to identify additional targets in neoplastic MCs, and to develop new treatment strategies.14-16 One promising approach may be to investigate survival/death-related molecules that are expressed in neoplastic MCs.14,24-29 In fact, several members of the Bcl-2 family have been described to be expressed in neoplastic MCs in SM and have been implicated in malignant cell growth.24-29 It has also been described that targeting of Bcl-2 family members, such as Mcl-1, in neoplastic MCs is associated with decreased survival and growth arrest.29

Several lines of evidence suggest that antiapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family can bind to and can be neutralized by “proapoptotic” Bcl-2 family members such as Bim.30-34 In fact, Bim is a BH3-only protein of the Bcl-2 family that acts proapoptotically in various tissues and cells.30-34 It has also been described that expression of Bim is suppressed in neoplastic cells in various myeloid neoplasms, and that re-expression of Bim in these cells is associated with decreased survival and apoptosis.35-38

Recently, Möller et al have shown that the KIT ligand stem cell factor (SCF) promotes MC survival by depressing the expression and function of Bim.39 However, so far, expression of Bim has not been analyzed in the context of mastocytosis.

In the present study, we show that neoplastic MCs in SM display only low levels of Bim, that the SM-related oncoprotein KIT D816V as well as the SCF-activated wild type receptor (wt KIT) down-regulate expression of Bim, and that (drug-induced) re-expression of Bim in neoplastic MCs is associated with inhibition of proliferation and decreased survival.

Methods

Reagents

PKC412 (midostaurin) was kindly provided by Dr Johannes Roesel and Dr Doriano Fabbro (Novartis Pharma AG). Stock solutions of PKC412 were prepared by dissolving in dimethyl-sulfoxide (Merck). The BH3 mimetic obatoclax (GX15-070) that blocks all relevant antiapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, was kindly provided by Dr Jean Viallet (GeminX Pharmaceuticals). Bortezomib (Velcade) was purchased from Janssen-Cilag; recombinant human (rh) SCF, from Strathmann Biotech; RPMI 1640 medium and fetal calf serum (FCS), from PAA Laboratories; rh interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-6, from Peprotech; rh IL-3, from Novartis; Iscove modified Dulbecco medium, from Gibco Life Technologies; and 3H-thymidine, from Amersham.

HMC-1 cells expressing or lacking KIT D816V

The human MC line HMC-1, generated from a patient with MCL,40 was kindly provided by Dr Joseph H. Butterfield (Mayo Clinic). Two subclones of HMC-1 were used, namely HMC-1.1 exhibiting the KIT mutation V560G but not D816V, and a second subclone, HMC-1.2, harboring both KIT mutations (ie, V560G and D816V).11,20 HMC-1 cells were maintained in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with 10% FCS, l-glutamine, and antibiotics at 37°C and 5% CO2. HMC-1 cells were rethawed from an original stock every 4 to 8 weeks and were passaged weekly. HMC-1 cells were periodically checked for (1) the presence of metachromatic granules, (2) expression of KIT, and (3) the down-modulating effect of IL-4 on KIT expression.41

Ba/F3 cells with inducible expression of wt KIT or KIT D816V

The generation of Ba/F3 cells with doxycycline-inducible expression of wild-type (wt) KIT (Ton.Kit.wt) or KIT D816V has recently been described.20,42 In brief, Ba/F3 cells expressing the reverse tet-transactivator were cotransfected with pTRE2 vector (Clontech) containing KIT D816V cDNA or wt KIT cDNA by electroporation.42 Stably transfected cells were selected by growing in hygromycin and were cloned by limiting dilution. Subclone Ton.Kit.D816V.2742 was used in all experiments. Expression of KIT D816V can be induced in Ton.Kit.D816V.27 cells within 12 hours by exposure to doxycycline (1 μg/mL).42 In addition, we used Ton.Kit.wt cells.42 In these cells, expression of wt KIT was induced by doxycycline, and activation of KIT was initiated by addition of SCF (100 ng/mL).20,42

Isolation and culture of primary mast cells

Primary neoplastic bone marrow (BM) MCs were obtained from 3 patients with ASM and 1 with MCL. Normal BM cells were obtained from 3 donors who underwent lymphoma staging. Informed consent was obtained in each case before BM puncture in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Vienna. BM aspirates were collected in syringes containing preservative-free heparin. Cells were layered over Ficoll to isolate mononuclear cells (MNCs). MNC fractions contained 5% to 10% MCs in patients with ASM, and less than 1% MCs in normal BM samples. Cell viability was more than 90%. In all patients with SM analyzed, the presence of the KIT mutation D816V in BM MNCs could be confirmed by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis.42

Normal MCs were generated in cord blood (CB) cell cultures as reported.43-45 In brief, CD133+ progenitors were isolated from CB MNCs using magnetic microbeads and the QuadroMACS magnetic separator according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of isolated CD133+ cells amounted to more than 97%. Isolated cells (0.5 × 106/mL) were cultured in 6-well plates (Costar) in Stem Span serum-free medium (CellSystems) supplemented with SCF (100 ng/mL), IL-6 (100 ng/mL), and IL-3 (30 ng/mL) for 2 weeks, and thereafter in medium containing SCF and IL-6 without IL-3. After 4 weeks, RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS was used instead of serum-free medium. Cytokines were replaced weekly. After 7 weeks, 70% to 80% of cells were mature MCs as evidenced by Wright-Giemsa staining. To induce apoptosis and Bim expression in MCs, cells were starved from SCF for up to 5 days before being analyzed.

Treatment with inhibitors

In typical experiments, HMC-1 cells, Ba/F3 cells containing wt KIT or KIT D816V, or primary neoplastic cells were incubated with PKC412 (midostaurin; 0.01-1μM) at 37°C for up to 24 hours. The BH3 mimetic obatoclax was applied to HMC-1 cells at various concentrations (0.01-10μM) for 24 or 48 hours. In a separate set of experiments, HMC-1 cells were exposed to the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (1pM to 100μM) for up to 48 hours. To determine potential synergistic drug interactions, HMC-1 cells were incubated with combinations of PKC412 and bortezomib or combinations of PKC412 and obatoclax at suboptimal concentrations. CB-derived MCs were incubated in the presence or absence of PKC412 (0.01-1.0μM), bortezomib (0.01-1.0μM), or obatoclax (0.1, 1.0, and 10μM) at 37°C for 24 or 48 hours.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Northern blotting was performed as described38,46 using 32P-labeled cDNAs specific for Bim and β-actin. Primers for PCR amplification of cDNA probes (VBC Genomics) were human Bim forward: 5′-CCCGCGGAATTCATGGAATACATGCCAATGGAA-3′, human Bim reverse: 5′-GGGCGCGAATTCTCAATGCCTTCTCCATACCAG-3′; human β-actin forward: 5′-ATGGATGATGATATCGCCGCG-3′, human β-actin reverse: 5′-CTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGGACGATGGAGGGGCC-3′. Expression of mRNA levels and of protein expression levels was quantified by densitometry using the EASY Win32 software (Herolab).

Western blot analysis and immunocytochemistry

Western blot experiments were conducted using HMC-1 cells, cultured normal MCs, and Ton.Kit cells. Western blotting was performed as described38 using a polyclonal rabbit antibody against BimEL (Sigma), and an anti–β-actin antibody (Sigma). In select experiments, expression of total and phosphorylated KIT in drug-exposed HMC-1 cells was examined by Western blotting and immunoprecipitation (IP) as described previously.20,23 In brief, cells were incubated in control medium or 1μM PKC412 at 37°C for 4 hours. Then, IP was performed on cell lysates (107 cells) using anti-KIT antibodies and anti–phospho-tyr monoclonal antibody 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology) as reported.20 Antibody reactivity was made visible by sheep anti–mouse IgG or donkey anti–rabbit IgG and Lumingen PS-3 detection reagent (Amersham). Immunocytochemistry was performed on cytospin preparations of HMC-1 cells, primary neoplastic MCs obtained from a patient with MCL, cultured MCs, as well as primary cells obtained from normal BM. Immunocytochemical staining was performed as described38 using a polyclonal goat anti-Bim antibody (dilution 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and a biotinylated rabbit anti–goat IgG (Biocare). As chromogen, alkaline phosphatase complex (Biocare) was used. Antibody reactivity was made visible by Neofuchsin (Nichirei).

Transfection of HMC-1 cells with a Bim-specific siRNA

To analyze the functional role of Bim, we applied an annealed, purified, and desalted double-stranded Bim siRNA (CUACCUCCCUACAGACAGAdTdT) and a control siRNA against luciferase (CUUACGCUGAGUACUUCGA; both from Dharmacon).38 For transfection, 1.5 × 106 HMC-1 cells were seeded in 75-cm2 culture plates at 37°C for 24 hours. siRNAs were complexed with Lipofectin-Reagent (Invitrogen; 10 μg/mL) as described by the supplier. HMC-1 cells were incubated with 200nM Bim siRNA or with 200nM luciferase siRNA at 37°C for 4 hours. Then, cells were incubated with control medium or PKC412 (1μM) at 37°C for 24 hours. Thereafter, cells were subjected to Western blot analysis and the numbers (percentage) of apoptotic cells were determined by microscopy or/and by annexin V staining.

Real-time PCR analysis

RNA was isolated from HMC-1 cells or CB-derived cultured MCs using the RNeasy MinEluteCleanupKit (QIAGEN). cDNA was synthesized using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), random primers, first-strand buffer, deoxynucleotide triphosphates (100mM), and RNasin (all from Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCR was performed essentially as described42 using primers specific for human Bim and ABL: Bim forward: 5′-TGTCTGACTCTGACTCTCTGACTGA-3′, reverse: 5′-GAAGGTTGCTTTGCCATTTGGTC-3′; ABL forward: 5′-TGTATGATTTTGTGGCCAGTGGAG-3′, reverse: 5′-GCCTAAGACCCGGAGCTTTTCA-3′. mRNA levels for Bim were normalized by comparing with ABL mRNA levels.

Determination of proliferation by 3H-thymidine uptake experiments

For determination of 3H-thymidine uptake, cells were cultured in 96-well microtiter plates (5 × 104 cells/well) in the absence or presence of various concentrations of PKC412 (60nM to 1μM) or bortezomib (1nM to 100μM) for 48 hours. To determine cooperative drug effects, various combinations of inhibitors were applied. After incubation, 1 μCi (0.037 MBq) 3H-thymidine was added. Twelve hours later, cells were harvested on filter membranes, and bound radioactivity was measured in a β-counter (Top-Count NXT; Packard Bioscience). All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Evaluation of apoptosis by light microscopy, flow cytometry, and TUNEL assay

The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined on Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospin slides. Apoptosis was defined by established cytomorphologic criteria.47 Cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion. For flow cytometric determination of apoptosis, combined annexin V/propidium iodide staining was performed. HMC-1.1 cells, HMC-1.2 cells, or cultured CB-derived MCs were exposed to various concentrations of PKC412, bortezomib, or control medium at 37°C for 24 or 48 hours. Thereafter, cells were washed and incubated with annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate (Bender MedSystems) in binding buffer containing HEPES (10mM, pH 7.4), NaCl (140mM), and CaCl2 (2.5mM). Thereafter, propidium iodide, 1 μg/mL (Bender MedSystems), was added. Cells were then washed and analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson). To confirm apoptosis in HMC-1 cells after exposure to bortezomib, a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine-triphosphatase-biotin nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed using In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit Fluorescein (Roche Diagnostics) essentially as described.23 In brief, cells were placed on cytospin slides, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at pH 7.4 at room temperature for 60 minutes, washed, and then permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% sodium citrate. Thereafter, the cells were washed and incubated in the terminal-transferase reaction solution containing CoCl2, terminal deoxy-nucleotidyltransferase, and fluorescein-labeled deoxyuridine triphosphate for 60 minutes at 37°C. Cells were then washed and analyzed with a Nikon Eclipse E 800 fluorescence microscope.

Statistical analysis

To determine the level of significance in cell growth experiments, the paired Student t test was applied. Results were considered significantly different when the P value was less than .05. To determine synergistic drug effects, combination index values were calculated using a commercially available software (Calcusyn; Biosoft).48

Results

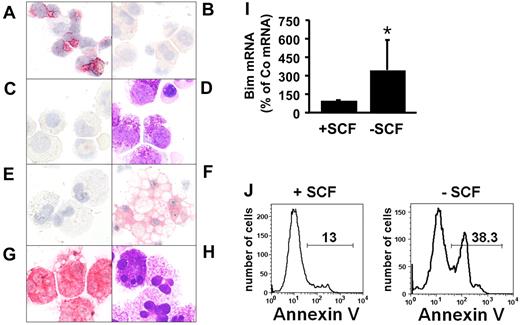

Primary neoplastic mast cells in SM express low levels of Bim

As visible in Figure 1A, myeloid progenitor cells obtained from normal BM displayed detectable levels of immunoreactive Bim, confirming previous data.38 By contrast, neoplastic MCs obtained from the BM of patients with advanced SM (ASM, MCL) did not express detectable Bim by immunocytochemistry (Figure 1B-C). We were also unable to detect substantial amounts of Bim in HMC-1 cells or in cultured CB-derived human MCs kept in SCF (Figure 1E). However, when starved from SCF, cultured MCs were found to express detectable levels of Bim. Expression of Bim in these MCs was accompanied by morphologic signs of apoptosis, which was particularly observed in Bim-positive MCs (Figure 1F). In addition, starvation of cultured MCs from SCF was followed by an increase in Bim mRNA expression (Figure 1I) and by an increase in the number of annexin V-positive cells assessed by flow cytometry (Figure 1J). Together, these data suggest that expression of Bim is suppressed in neoplastic MCs, and that expression of Bim in normal MCs can be down-regulated by a KIT-dependent mechanism, confirming the data of Möller et al.39

Immunocytochemical detection of Bim in normal bone marrow cells and mast cells. (A) Mononuclear cells obtained from normal bone marrow (BM); (B) neoplastic mast cells (MCs) obtained from the BM of a patient with ASM; and (C) neoplastic MCs obtained from the BM of a patient with MCL. Immunocytochemistry was performed using an antibody against Bim. (D) Wright-Giemsa staining of neoplastic MCs in a patient with MCL. (E-F) Cord blood–derived cultured MCs were kept in SCF, 100 ng/mL (E) or were starved from SCF (F) for 5 days (37°C). Then, cells were harvested, spun on cytospin slides, and stained with an anti-Bim antibody. (G-H) Tryptase stain (G) and Wright-Giemsa stain (H) of cultured cord blood–derived MCs kept in SCF. Figures shown in panels A through H (magnification, ×400 each) were prepared using an Olympus DP11 camera connected to an Olympus BX50F4 microscope equipped with 100×/1.35 UPlan-Apo objective lens (Olympus). Images were prepared using Adobe Photoshop CS2 software Version 9.0 (Adobe Systems) and processed with PowerPoint software (Microsoft). (I) Real-time PCR performed on cultured cord blood–derived mast cells kept in medium with (+SCF) or without (−SCF) SCF for 2 days. PCR was performed using primers specific for Bim and ABL. Expression of Bim mRNA is expressed as percentage of control (= ABL mRNA levels = 100%) and represents the mean ± SD of 6 independent experiments. *P < .05. (J) Apoptosis-inducing effect of SCF starvation on cultured cord blood–derived MCs. MCs were kept in the presence (+SCF, left panel) or absence (−SCF, right panel) of 100 ng/mL SCF for 5 days, and then were subjected to annexin V staining and flow cytometry.

Immunocytochemical detection of Bim in normal bone marrow cells and mast cells. (A) Mononuclear cells obtained from normal bone marrow (BM); (B) neoplastic mast cells (MCs) obtained from the BM of a patient with ASM; and (C) neoplastic MCs obtained from the BM of a patient with MCL. Immunocytochemistry was performed using an antibody against Bim. (D) Wright-Giemsa staining of neoplastic MCs in a patient with MCL. (E-F) Cord blood–derived cultured MCs were kept in SCF, 100 ng/mL (E) or were starved from SCF (F) for 5 days (37°C). Then, cells were harvested, spun on cytospin slides, and stained with an anti-Bim antibody. (G-H) Tryptase stain (G) and Wright-Giemsa stain (H) of cultured cord blood–derived MCs kept in SCF. Figures shown in panels A through H (magnification, ×400 each) were prepared using an Olympus DP11 camera connected to an Olympus BX50F4 microscope equipped with 100×/1.35 UPlan-Apo objective lens (Olympus). Images were prepared using Adobe Photoshop CS2 software Version 9.0 (Adobe Systems) and processed with PowerPoint software (Microsoft). (I) Real-time PCR performed on cultured cord blood–derived mast cells kept in medium with (+SCF) or without (−SCF) SCF for 2 days. PCR was performed using primers specific for Bim and ABL. Expression of Bim mRNA is expressed as percentage of control (= ABL mRNA levels = 100%) and represents the mean ± SD of 6 independent experiments. *P < .05. (J) Apoptosis-inducing effect of SCF starvation on cultured cord blood–derived MCs. MCs were kept in the presence (+SCF, left panel) or absence (−SCF, right panel) of 100 ng/mL SCF for 5 days, and then were subjected to annexin V staining and flow cytometry.

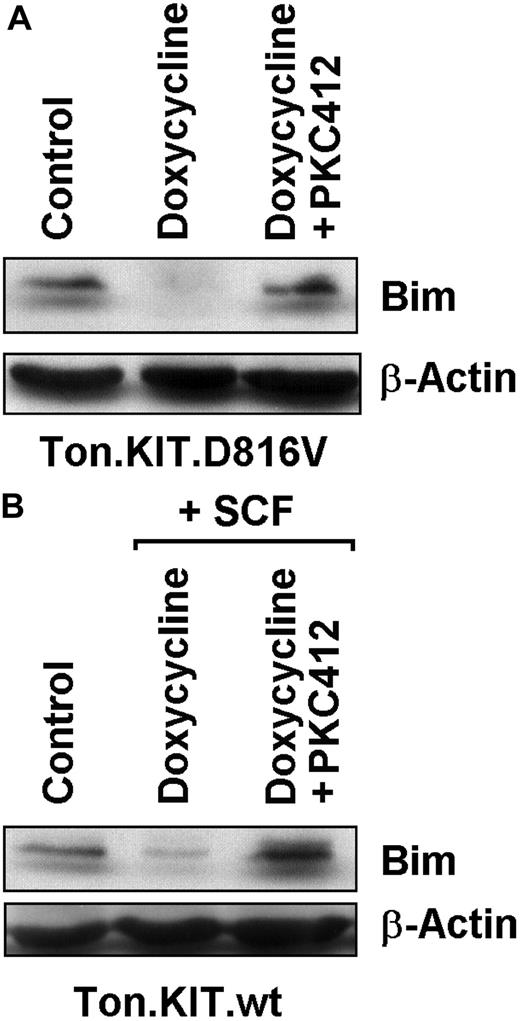

KIT D816V and SCF-activated wt KIT down-regulate expression of Bim in Ba/F3 cells

We next asked whether the major oncogenic KIT mutant, KIT D816V, suppresses expression of Bim in neoplastic cells. For this purpose we used Ton.Kit.D816V.27 cells and Ton.Kit.wt cells, in which KIT variants (KIT D816V and wt KIT, respectively) can be expressed conditionally upon addition of doxycycline.42 In our experiments, the doxycycline-induced expression of KIT D816V as well as the doxycycline-induced expression of wt KIT (exposed to SCF to induce KIT activation) resulted in a substantial decrease in expression of Bim in Ba/F3 cells. As shown in Figure 2, the KIT D816V–induced decrease in expression of Bim and the (SCF-activated) wt KIT–induced decrease in Bim expression in these cells were both abrogated by addition of PKC412 (1μM). In control experiments, doxycycline did not modulate Bim expression in nontransfected Ba/F3 cells, and PKC412 did not rescue Ba/F3 cells from BCR/ABL-induced down-regulation of Bim (data not shown).

Effects of PKC412 on expression of Bim in Ton.Kit cells. (A) Ton.Kit.D816V cells were grown in control medium (control), or in the presence of doxycycline to induce KIT D816V expression. KIT D816V–positive cells were cultured in control medium (doxycycline) or in the presence of PKC412 (1μM) for 12 hours. Thereafter, cells were subjected to Western blotting performed with an antibody against Bim. The β-actin loading control is also shown. (B) Ton.Kit.wt cells were grown in control medium (control) or in the presence of doxycycline and stem cell factor (SCF; for induction of wt KIT). Wt KIT–positive cells were cultured in control medium (doxycycline + SCF) or in the presence of PKC412 (1μM) for 12 hours. Then, Western blotting was performed using antibodies against Bim and β-actin.

Effects of PKC412 on expression of Bim in Ton.Kit cells. (A) Ton.Kit.D816V cells were grown in control medium (control), or in the presence of doxycycline to induce KIT D816V expression. KIT D816V–positive cells were cultured in control medium (doxycycline) or in the presence of PKC412 (1μM) for 12 hours. Thereafter, cells were subjected to Western blotting performed with an antibody against Bim. The β-actin loading control is also shown. (B) Ton.Kit.wt cells were grown in control medium (control) or in the presence of doxycycline and stem cell factor (SCF; for induction of wt KIT). Wt KIT–positive cells were cultured in control medium (doxycycline + SCF) or in the presence of PKC412 (1μM) for 12 hours. Then, Western blotting was performed using antibodies against Bim and β-actin.

Effects of PKC412 on expression of Bim in neoplastic MCs

To examine the role of KIT D816V (and of KIT V560G) in the regulation of Bim expression in neoplastic MCs, HMC-1 cells and the multitargeted drug PKC412, a drug that inhibits growth of neoplastic MCs and the TK activity of wt KIT, KIT D816V, and KIT V560G, were used. Two HMC-1 subclones were examined, that is, HMC-1.1 (display KIT V560G) and HMC-1.2 (expressing KIT V560G and KIT D816V). In both subclones, PKC412 decreased the expression of phosphorylated KIT (Figure 3A) in HMC-1 cells, confirming previous data,20 and induced the expression of the Bim protein as evidenced by Western blotting (Figure 3B) and immunostaining (not shown). In addition, PKC412 was found to promote the expression of Bim mRNA in HMC-1 cells as evidenced by Northern blotting (Figure 3C-D) and real-time PCR (Figure 3E-F). PKC412 effects on Bim expression in the 2 HMC-1 subclones were significant at 0.1μM (P < .05), with more pronounced effects seen in HMC-1.2 cells than in HMC-1.1 cells (P > .05). The growth-inhibitory effects of PKC412 on neoplastic MCs were also confirmed in our experiments. All in all, these data suggest that oncogenic KIT plays an important role in suppression of Bim in neoplastic MCs.

Effects of PKC412 and bortezomib on expression of Bim in HMC-1 cells. (A) Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blot (WB) were performed with HMC-1 cells exposed to PKC412 (midostaurin, 1μM) or control medium (control) at 37°C for 4 hours. IP and WB were performed as described in “Methods.” For detection of phospho-KIT (p-KIT), anti–phospho-tyr monoclonal antibody 4G10 (1:1000) was applied. As visible, midostaurin suppressed the expression of p-KIT in HMC-1.1 and HMC-1.2 cells (top panels) without affecting total KIT expression (bottom panels). (B) WB analysis of HMC-1.1 cells (left panel) and HMC-1.2 cells (right panel) exposed to control medium (control) or PKC412 (1μM) for 12 hours. WB was performed using a polyclonal anti-Bim antibody. The β-actin loading control is also shown. (C-D) Northern blot analysis of HMC-1.1 cells (C) and HMC-1.2 cells (D) exposed to control medium (control) or PKC412 (1μM) for 12 hours. Northern blotting was performed using a Bim-specific cDNA probe. Equal loading was confirmed by probing for β-actin mRNA. (E-H) Real-time PCR analysis of Bim mRNA expression in HMC-1.1 cells (E,G) and HMC-1.2 cells (F,H) exposed to control medium (0) or various concentrations of PKC412 or bortezomib as indicated for 24 hours. Bim mRNA levels are expressed as percentage of ABL mRNA and represent the mean ± SD of 8 independent experiments performed with PKC412, and mean ± SD of 7 independent experiments performed with bortezomib. *P < .05. (I-J) Cultured cord blood–derived MCs were incubated in control medium (Co) or various concentrations of PKC412 or bortezomib (as indicated) for 24 hours. Thereafter, Bim mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR and are expressed as percentage of ABL mRNA expression. In panel J, mean ± SD values from 3 independent experiments are shown. (K) Cultured cord blood–derived MCs were incubated in control medium (left panel), PKC412 (1μM, middle), or bortezomib (1μM, right panel) for 48 hours. Thereafter, cells were examined for apoptosis by annexin V staining and flow cytometry. The percentage of apoptotic cells is also shown (control: 9%, PKC412: 12%, bortezomib: 60%).

Effects of PKC412 and bortezomib on expression of Bim in HMC-1 cells. (A) Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blot (WB) were performed with HMC-1 cells exposed to PKC412 (midostaurin, 1μM) or control medium (control) at 37°C for 4 hours. IP and WB were performed as described in “Methods.” For detection of phospho-KIT (p-KIT), anti–phospho-tyr monoclonal antibody 4G10 (1:1000) was applied. As visible, midostaurin suppressed the expression of p-KIT in HMC-1.1 and HMC-1.2 cells (top panels) without affecting total KIT expression (bottom panels). (B) WB analysis of HMC-1.1 cells (left panel) and HMC-1.2 cells (right panel) exposed to control medium (control) or PKC412 (1μM) for 12 hours. WB was performed using a polyclonal anti-Bim antibody. The β-actin loading control is also shown. (C-D) Northern blot analysis of HMC-1.1 cells (C) and HMC-1.2 cells (D) exposed to control medium (control) or PKC412 (1μM) for 12 hours. Northern blotting was performed using a Bim-specific cDNA probe. Equal loading was confirmed by probing for β-actin mRNA. (E-H) Real-time PCR analysis of Bim mRNA expression in HMC-1.1 cells (E,G) and HMC-1.2 cells (F,H) exposed to control medium (0) or various concentrations of PKC412 or bortezomib as indicated for 24 hours. Bim mRNA levels are expressed as percentage of ABL mRNA and represent the mean ± SD of 8 independent experiments performed with PKC412, and mean ± SD of 7 independent experiments performed with bortezomib. *P < .05. (I-J) Cultured cord blood–derived MCs were incubated in control medium (Co) or various concentrations of PKC412 or bortezomib (as indicated) for 24 hours. Thereafter, Bim mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR and are expressed as percentage of ABL mRNA expression. In panel J, mean ± SD values from 3 independent experiments are shown. (K) Cultured cord blood–derived MCs were incubated in control medium (left panel), PKC412 (1μM, middle), or bortezomib (1μM, right panel) for 48 hours. Thereafter, cells were examined for apoptosis by annexin V staining and flow cytometry. The percentage of apoptotic cells is also shown (control: 9%, PKC412: 12%, bortezomib: 60%).

Role of the proteasome in KIT D816V–induced down-modulation of Bim

Recent data suggest that degradation of phosphorylated Bim in neoplastic myeloid cells is mediated through a pathway involving the proteasome.36,38 In the current study, we asked whether a proteasome-related degradation pathway is involved in KIT D816V–induced down-regulation of Bim in neoplastic MCs. To address this question, we applied the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib on neoplastic MCs (HMC-1 cells). In these experiments, incubation of HMC-1.1 cells and HMC-1.2 cells with bortezomib (10nM to 1μM) resulted in an increased expression of Bim mRNA as evidenced by real-time PCR (Figure 3G-H). The bortezomib-induced increase in Bim mRNA expression was slightly higher in HMC-1.2 cells than in HMC-1.1 cells (P > .05). Finally, as determined by immunocytochemistry, exposure of HMC-1 cells to bortezomib (48 hours) resulted in an increased expression of the Bim protein as determined by immunocytochemistry (not shown). These data suggest that proteasomal degradation may be involved in molecular mechanisms leading to a decrease in Bim mRNA expression and Bim protein expression in neoplastic MCs. We also found that bortezomib induces Bim mRNA expression and apoptosis in normal cultured CB-derived MCs, whereas PKC412 showed little if any effect on Bim expression or survival in CB-derived MCs over the time range tested (48 hours; Figure 3I-K).

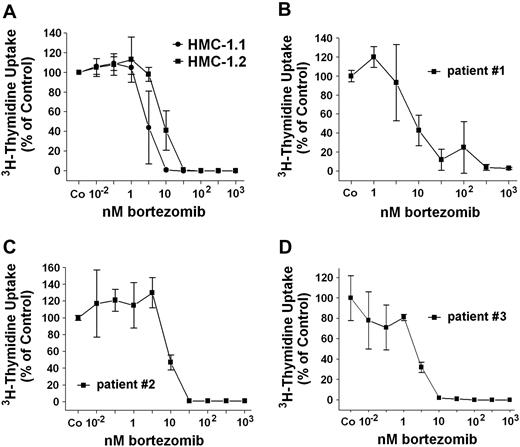

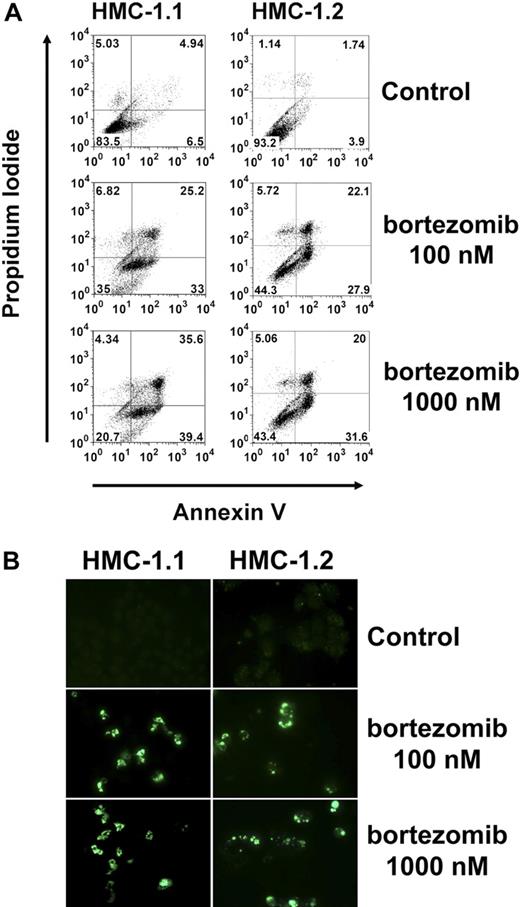

Effects of bortezomib on growth and viability of neoplastic MCs

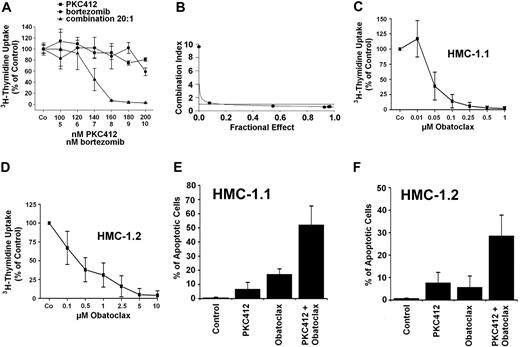

The striking effect of bortezomib on “Bim re-expression” prompted us to examine the effects of this proteasome inhibitor on growth of neoplastic MCs. As shown in Figure 4A, bortezomib inhibited the proliferation of HMC-1.1 cells and HMC-1.2 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, bortezomib was found to counteract 3H-thymidine uptake in primary neoplastic MCs obtained from 3 patients with SM (Figure 4B-D). In a next step, we investigated the effects of bortezomib on induction of apoptosis in neoplastic MCs. As assessed by combined annexin V/propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry (Figure 5A), we were able to show that incubation of HMC-1.1 cells and HMC-1.2 cells with various concentrations of bortezomib leads to a dose-dependent induction of apoptosis, and corresponding results were obtained in a TUNEL assay (Figure 5B). In control experiments, bortezomib did not inhibit the expression or phosphorylation of KIT in HMC-1 cells (not shown). We next asked whether bortezomib and PKC412 would produce synergistic effects on growth of neoplastic MCs. To address this question, drug combination experiments were conducted. In these experiments PKC412 was found to synergize with bortezomib in producing growth inhibition in HMC-1.1 cells (not shown) as well as in HMC-1.2 cells (Figure 6A-B). These data suggest that a strategy attempting to up-regulate Bim in neoplastic MCs by more than one mechanism may be an interesting approach to counteract malignant cell growth. Finally, we asked whether bortezomib or PKC412 would also produce growth inhibition in normal BM cells. In these experiments, bortezomib (100nM) was found to inhibit growth of normal BM MNCs, whereas PKC412 (up to 1μM) showed little if any effect. In addition, no additive or synergistic growth-inhibitory effects of bortezomib and PKC412 on normal BM MNCs were seen (not shown).

Effects of bortezomib on growth of neoplastic MCs. (A) HMC-1.1 cells and HMC-1.2 cells were incubated in control medium (Co) or in medium containing various concentrations of bortezomib (as indicated) at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 48 hours. Then, 3H-thymidine uptake was determined. Results are expressed as percentage of control (Co) and show the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (B-D) Primary BM MNCs obtained from 3 patients with ASM (B, no. 1; C, no. 2; D, no. 3) were incubated in control medium (Co) or in various concentrations of bortezomib at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 48 hours before 3H-thymidine uptake was measured. Results are expressed as percentage of control (Co) and show the mean ± SD of triplicates.

Effects of bortezomib on growth of neoplastic MCs. (A) HMC-1.1 cells and HMC-1.2 cells were incubated in control medium (Co) or in medium containing various concentrations of bortezomib (as indicated) at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 48 hours. Then, 3H-thymidine uptake was determined. Results are expressed as percentage of control (Co) and show the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (B-D) Primary BM MNCs obtained from 3 patients with ASM (B, no. 1; C, no. 2; D, no. 3) were incubated in control medium (Co) or in various concentrations of bortezomib at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 48 hours before 3H-thymidine uptake was measured. Results are expressed as percentage of control (Co) and show the mean ± SD of triplicates.

Flow cytometric determination of apoptosis by combined annexin V/propidium iodide and by TUNEL assay. (A) HMC-1.1 cells (left panel) and HMC-1.2 cells (right panel) were exposed to bortezomib (100nM, middle panel; 1μM, right panel) or control medium (top panel) at 37°C for 24 hours. Thereafter, cells were washed and incubated with annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate. Then, propidium iodide was added. Cells were then washed and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Determination of apoptosis by TUNEL assay. HMC-1.1 cells (left panel) and HMC-1.2 cells (right panel) were exposed to bortezomib (100nM, middle panel; 1μM, right panel) or control medium (top panel) at 37°C for 24 hours. Thereafter, a TUNEL assay was performed as described in “Methods.” Cells were analyzed on a Nikon Eclipse E 800 fluorescence microscope (Nikon) equipped with 100×/1.35 UPlan-Apo objective lens (Olympus). Figure acquisition was performed using Olympus DP11 camera and Adobe Photoshop CS2 software Version 9.0 (Adobe Systems). Magnification, ×400.

Flow cytometric determination of apoptosis by combined annexin V/propidium iodide and by TUNEL assay. (A) HMC-1.1 cells (left panel) and HMC-1.2 cells (right panel) were exposed to bortezomib (100nM, middle panel; 1μM, right panel) or control medium (top panel) at 37°C for 24 hours. Thereafter, cells were washed and incubated with annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate. Then, propidium iodide was added. Cells were then washed and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Determination of apoptosis by TUNEL assay. HMC-1.1 cells (left panel) and HMC-1.2 cells (right panel) were exposed to bortezomib (100nM, middle panel; 1μM, right panel) or control medium (top panel) at 37°C for 24 hours. Thereafter, a TUNEL assay was performed as described in “Methods.” Cells were analyzed on a Nikon Eclipse E 800 fluorescence microscope (Nikon) equipped with 100×/1.35 UPlan-Apo objective lens (Olympus). Figure acquisition was performed using Olympus DP11 camera and Adobe Photoshop CS2 software Version 9.0 (Adobe Systems). Magnification, ×400.

Synergistic drug effects on growth/survival of neoplastic mast cells. (A) HMC-1.2 cells were incubated in control medium (Co) or in medium containing drugs at 37°C for 48 hours. After incubation with PKC412 (■), bortezomib (●), or drug combinations (▴), cells were analyzed for 3H-thymidine uptake. Results show 3H-thymidine uptake as percentage of control (100%) and represent the mean ± SD of triplicates. (B) Using CalcuSyn software, analyses of dose-effect relationships of PKC412 and bortezomib in HMC-1.2 cells were calculated according to the median effect method of Chou and Talalay.48 A combination index (CI) less than 1 indicates synergism. (C-D) HMC-1.1 cells (C) and HMC-1.2 cells (D) were incubated with increasing concentrations of obatoclax or control medium (Co) for 48 hours. Thereafter, 3H-thymidine uptake was determined. Results are expressed as percentage of control (Co) and represent the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (E-F) HMC-1.1 cells (E) and HMC-1.2 cells (F) were incubated with suboptimal concentrations of obatoclax (1μM) and PKC412 (200nM) alone or in combination at 37°C for 24 hours. Then, the numbers (percentage) of apoptotic cells were determined. Results represent the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. As assessed by the CalcuSyn program all drug combination effects were found to be synergistic in nature.

Synergistic drug effects on growth/survival of neoplastic mast cells. (A) HMC-1.2 cells were incubated in control medium (Co) or in medium containing drugs at 37°C for 48 hours. After incubation with PKC412 (■), bortezomib (●), or drug combinations (▴), cells were analyzed for 3H-thymidine uptake. Results show 3H-thymidine uptake as percentage of control (100%) and represent the mean ± SD of triplicates. (B) Using CalcuSyn software, analyses of dose-effect relationships of PKC412 and bortezomib in HMC-1.2 cells were calculated according to the median effect method of Chou and Talalay.48 A combination index (CI) less than 1 indicates synergism. (C-D) HMC-1.1 cells (C) and HMC-1.2 cells (D) were incubated with increasing concentrations of obatoclax or control medium (Co) for 48 hours. Thereafter, 3H-thymidine uptake was determined. Results are expressed as percentage of control (Co) and represent the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (E-F) HMC-1.1 cells (E) and HMC-1.2 cells (F) were incubated with suboptimal concentrations of obatoclax (1μM) and PKC412 (200nM) alone or in combination at 37°C for 24 hours. Then, the numbers (percentage) of apoptotic cells were determined. Results represent the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. As assessed by the CalcuSyn program all drug combination effects were found to be synergistic in nature.

Effects of the BH3 mimetic obatoclax on growth and survival of neoplastic MCs

Obatoclax is known to induce apoptosis in various neoplastic cells by targeting antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members and thus promoting/mimicking effects of Bim and other death regulators. In the present study, obatoclax was found to inhibit 3H-thymidine uptake in a dose-dependent manner in HMC-1.1 cells (IC50: 0.01-0.05μM) and HMC-1.2 cells (IC50: 0.5μM; Figure 6C-D), and to induce apoptosis in both subclones. In addition, obatoclax was found to induce apoptosis in HMC-1.1 cells and HMC-1.2 cells in a dose-dependent manner, with up to 50% apoptotic cells seen at higher drug concentrations (5-10μM). Moreover, obatoclax was found to synergize with PKC412 in producing apoptosis in HMC-1.1 and HMC-1.2 cells (Figure 6E-F). These data show that the BH3 mimetic drug obatoclax is a potent inhibitor of growth and survival of neoplastic MCs, and that the drug acts synergistically with PKC412.

Inhibition of drug-induced re-expression of Bim by siRNA rescues neoplastic MCs from drug-induced apoptosis

To provide definitive evidence for the functional significance of drug-induced Bim (re)-expression and Bim action in neoplastic MCs, expression of Bim was specifically silenced by an siRNA approach. For this purpose, HMC-1 cells were transfected with an siRNA targeting Bim and cultured in the presence or absence of PKC412. After transfection of HMC-1 cells with Bim siRNA, the ability of PKC412 to induce expression of Bim was markedly reduced compared with HMC-1 cells transfected with a control siRNA (Figure 7A-B). The effect of the Bim siRNA was seen in both subclones (ie, in HMC-1.1 cells and HMC-1.2 cells). Furthermore, we were able to show that the siRNA-induced knockdown of Bim rescues HMC-1 cells from PKC412-induced apoptosis (Figure 7A-D) as well as from bortezomib-induced apoptosis (Figure 7D). The rescue effect of the Bim siRNA in PKC412-exposed cells was demonstrable by microscopy (Figure 7A-B) as well as by annexin V staining (Figure 7C). These data suggest that in drug-exposed cells, re-expressed Bim may play a functional role as a death regulator in neoplastic MCs, and thus contribute to the antineoplastic action exerted by the multikinase/KIT inhibitor PKC412.

Effects of PKC412 on neoplastic human MCs transfected with a Bim-specific siRNA. (A-B) Top panel: Western blot analysis of expression of Bim in HMC-1.1 cells (A) and HMC-1.2 cells (B) cultured in control medium (control) or PKC412 (1μM) for 24 hours. PKC412 was applied on nontransfected cells, on HMC-1 cells transfected with a control siRNA against luciferase (luc-siRNA), and on HMC-1 cells transfected with a Bim-specific siRNA (bim-siRNA). Western blotting was performed using an antibody against Bim and an antibody against β-actin. (A-B) Bottom panel: Evaluation of effects of PKC412 (1μM, 24 hours) on apoptosis in HMC-1.1 cells (A) and HMC-1.2 cells (B). Results show percentages of apoptotic cells and are expressed as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments (*P < .05). (C) Annexin V stain of HMC-1 cells after transfection with a control siRNA against Luciferase (Luc; top panels) or a Bim-specific siRNA (bottom panels) and exposure to control medium (left panels) or PKC412 (1μM; right panels) for 24 hours. The percentage of apoptotic cells is also shown. (D) HMC-1.2 cells were transfected with 200nM control siRNA (Luciferase siRNA) or with 200nM siRNA directed against Bim as described in “Methods.” Thereafter, cells were split and kept in control medium or in the presence of PKC412 (1μM) or bortezomib (10nM) for 24 hours. After incubation, cells were spun on cytospin slides and stained by Wright-Giemsa. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by light microscopy. Results represent the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with Luciferase siRNA.

Effects of PKC412 on neoplastic human MCs transfected with a Bim-specific siRNA. (A-B) Top panel: Western blot analysis of expression of Bim in HMC-1.1 cells (A) and HMC-1.2 cells (B) cultured in control medium (control) or PKC412 (1μM) for 24 hours. PKC412 was applied on nontransfected cells, on HMC-1 cells transfected with a control siRNA against luciferase (luc-siRNA), and on HMC-1 cells transfected with a Bim-specific siRNA (bim-siRNA). Western blotting was performed using an antibody against Bim and an antibody against β-actin. (A-B) Bottom panel: Evaluation of effects of PKC412 (1μM, 24 hours) on apoptosis in HMC-1.1 cells (A) and HMC-1.2 cells (B). Results show percentages of apoptotic cells and are expressed as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments (*P < .05). (C) Annexin V stain of HMC-1 cells after transfection with a control siRNA against Luciferase (Luc; top panels) or a Bim-specific siRNA (bottom panels) and exposure to control medium (left panels) or PKC412 (1μM; right panels) for 24 hours. The percentage of apoptotic cells is also shown. (D) HMC-1.2 cells were transfected with 200nM control siRNA (Luciferase siRNA) or with 200nM siRNA directed against Bim as described in “Methods.” Thereafter, cells were split and kept in control medium or in the presence of PKC412 (1μM) or bortezomib (10nM) for 24 hours. After incubation, cells were spun on cytospin slides and stained by Wright-Giemsa. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by light microscopy. Results represent the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with Luciferase siRNA.

Discussion

The proapoptotic death regulator Bim has recently been identified as an important tumor suppressor in various myeloid neoplasms.32,35-38 In the present study, we provide evidence that the SM-related oncoprotein KIT D816V is involved in suppression of Bim in neoplastic MCs. Moreover, our data show that Bim, once re-expressed, acts as a potent inducer of apoptosis and thus mediates growth inhibition in neoplastic MCs. Finally, the results of our study show that the multikinase inhibitor midostaurin (PKC412) as well as the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib induce re-expression of Bim in neoplastic MCs, and counteract malignant cell growth. Re-expression of Bim may represent a novel attractive strategy to counteract antiapoptotic mechanisms in neoplastic MCs.

Several previous and more recent data suggest that Bim plays an essential role as a death regulator in various normal and neoplastic cells.30-38 In neoplastic cells, Bim is often suppressed by disease-related oncoproteins.36-38 Likewise, it has been described that the CML-related oncoprotein BCR/ABL leads to suppression of Bim in neoplastic cells.37,38 The results of our study suggest that the SM-related oncoprotein KIT D816V can suppress Bim expression in neoplastic cells. However, suppression of Bim is not restricted to the D816V-mutated variant of KIT, but is also seen with other KIT mutants (such as KIT V560G) and even was observed with SCF-activated wt KIT in Ba/F3 cells. These results are in line with the notion that SCF-activated KIT is an essential growth and survival factor for normal (physiologic) MCs,43,44,49-51 and with the observation that SCF deprivation causes Bim up-regulation as well as cell death in normal MCs, whereas exposure of MCs to SCF is associated with down-regulation of Bim.39,52,53 Correspondingly, we found that cultured CB-derived human MCs re-express Bim upon SCF deprivation, whereas continuous exposure to SCF is associated with Bim down-regulation in these cells. All in all, SCF/KIT-mediated suppression of Bim appears to be a general mechanism through which (long-term) survival of normal and neoplastic MCs may be maintained. Similar observations have also been reported for other oncoproteins such as BCR/ABL, and also for other death regulators and Bcl-2 family members.54-56

During the past few years, several effective KIT-targeting drugs have been identified.17-23 In the current study, we used the multikinase inhibitor midostaurin (PKC412) that counteracts the TK activity of wt KIT, KIT V560G, and KIT D186V, and thus the growth of neoplastic MCs.17,18,20 In the present study, exposure of neoplastic MCs to PKC412 was followed by re-expression of Bim and by consecutive cell death, a phenomenon that was seen in neoplastic HMC-1 cells harboring KIT D816V as well as in neoplastic MCs harboring KIT V560G but not KIT D816V. An interesting observation was that transfection of MCs with a Bim siRNA resulted in a rescue from PKC412-induced cell death. All in all, these data suggest that Bim re-expression is an important drug effect produced by PKC412, and that this effect contributes to drug-induced apoptosis in neoplastic MCs. Moreover, these data suggest that Bim suppression is a critical pro-oncogenic “event” in neoplastic MCs. Interestingly, in normal cultured mature MCs, PKC412 did not induce Bim expression or a substantial increase in apoptotic cells within 48 hours, contrasting the apoptosis-inducing effects of bortezomib. This is best explained by the fact that these cells are mature nondividing MCs and although their long-term survival depends on a functional SCF receptor (KIT), it may take longer until these cells go into apoptosis when exposed to PKC412 compared with neoplastic MCs.

Several recent studies have shown that Bim levels are regulated not only through posttransscriptional or posttranslational mechanisms or modulation of mRNA stability, but also by proteasomal degradation of Bim.34,36,38,57-59 Such proteasomal degradation may occur particularly when Bim is phosphorylated by physiologic stimuli (exposure to growth factors) or by certain oncoproteins.33,36,38,57-59 In the present study, we were able to show that inhibition of the proteasome by bortezomib is associated with a substantial increase in expression of Bim in HMC-1.1 cells and HMC-1.2 cells. Unexpectedly, bortezomib induced an increase not only in expression of the Bim protein but also in expression of Bim mRNA in HMC-1 cells. This may be explained by a direct effect of bortezomib on Bim mRNA expression or an effect of bortezomib on proteasomal degradation of proteins involved in Bim mRNA synthesis or the regulation of Bim mRNA stability. As assessed by quantitative real-time PCR, the effects real-time of bortezomib and PKC412 on Bim re-expression in HMC-1.1 cells and HMC-1.2 cells were similar in magnitude.

Based on the effect of bortezomib on Bim expression in neoplastic MCs, we also asked whether this proteasome inhibitor would suppress the growth and survival of neoplastic MCs. Indeed, bortezomib was found to inhibit proliferation in primary neoplastic MCs as well as in HMC-1 cells. As expected, the growth-inhibitory effects of bortezomib in HMC-1 cells were found to be associated with induction of apoptosis. An interesting observation was that the concentrations of bortezomib required to induce apoptosis (and to suppress proliferation) were slightly lower than that required to re-express Bim. These data suggest that bortezomib may block cell growth not only through re-expression of Bim, but also through other additional mechanisms that remain unknown so far. Another possibility may be that bortezomib induces not only Bim expression but also the expression of other BH3-only death regulators. Indeed, our recent data suggest that bortezomib induces not only expression of Bim mRNA but also the expression of Noxa mRNA and Puma mRNA in HMC-1 cells (S.C.-R., unpublished observation, May 2009). Alternatively, Bim acts as a death regulator in neoplastic mast cells at very low concentrations. In this regard it is noteworthy that Bim has been considered as a most potent death-inducing BH3-only protein.58,59

An interesting therapeutic approach may be to target antiapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family in neoplastic cells by applying BH3-mimetic drugs. One promising BH3 mimetic is obatoclax, a small molecule inhibitor that targets most if not all antiapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family.60-62 More recently, obatoclax has been introduced as a promising new anticancer agent in preclinical studies and in first clinical trials.63,64 In the present study, we found that obatoclax induces growth arrest and apoptosis in HMC-1.1 cells and HMC-1.2 cells. These data provide further evidence for the important role of Bcl-2 family members in growth and survival of neoplastic MCs, and suggest that obatoclax may be an interesting new agent to be considered for the treatment of advanced MC neoplasms.

Several efforts have recently been made to identify drug combinations that would exert major synergistic effects on growth of neoplastic MCs.20,23 Usually, drugs that act on different targets are selected in such approach. In the present study, we asked whether bortezomib and PKC412 or obatoclax and PKC412 would produce synergistic inhibitory effects on neoplastic MCs. Indeed, when combined, both drug combinations were found to synergize in producing growth inhibition and apoptosis in both subclones (ie, HMC-1.1 cells and HMC-1.2 cells). This is of particular interest because so far only very few drug combinations have been reported to exert synergistic effects on growth of KIT D816V+ neoplastic MCs.23

In summary, our data show that proapoptotic Bim is a major regulator of growth and survival of neoplastic human MCs, and that drug-induced re-expression of Bim or targeting of antiapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, preferably in combination with a KIT TK inhibitor, may be a novel interesting approach in advanced SM (ie, patients with ASM and MCL).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miriam Klauser and Andreas Repa for skillful technical assistance.

This study was supported by the Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung in Österreich, FWF grants P21173-B13 and SFB-F01820, and by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Science and Research (GENAU II, GZ 200.136/1-VI/1/2005), and the Hans und Blanca Moser Stiftung. A.G. and W.F.P. were supported by the Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung in Österreich, FWF grant SFB-F1816-B13.

Authorship

Contribution: K.J.A. performed research experiments on cell growth and drug interactions as well as Northern blot experiments, analyzed the data, and contributed to writing the article; K.V.G. performed experiments on KIT expression and phosphorylation as well as experiments on cell growth and drug interactions; I.M., A.G., and W.F.P. performed key laboratory experiments on cell growth, mast cell differentiation, and proliferation, and analyzed the data; S.C.-R. contributed immunostaining and PCR experiments; B.P. performed Western blot experiments and cell culture experiments using obatoclax; V.F. performed Northern blot experiments; M.K. and C.B. performed flow cytometry experiments; M.M. and C.S. established vital new analytical tools (Ba/F3 cells with inducible expression of KIT) and analyzed the data obtained with Ba/F3 cells; and P.V. designed the study, established the research plan, provided logistic and budget support, wrote the article, and approved the data and the final version of the article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Peter Valent, Department of Internal Medicine I, Division of Hematology and Hemostaseology, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, A-1090 Vienna, Austria; e-mail: peter.valent@meduniwien.ac.at

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal