Abstract

Abstract 2210

Poster Board II-187

Imatinib mesylate (IM), a targeted inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase, is widely used to treat chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). However, considerable number of patients fails to achieve or loose complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) or major molecular response (MMR). The mechanisms of failure in the majority of cases are unknown. Identification of patients who may subsequently fail to respond to imatinib would provide a considerable aid to clinical management. Few long-term retrospective population-based data on the outcome of these patients are available.

To identify prognostic factors that can predict failure of treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), and to optimise CML therapy after first line TKI failure.

The retrospective population-based analysis included 138 patients (68 females, 70 males, median age 47 yrs) in early chronic phase (ECP) (n=63), late chronic phase (LCP) (n=60) or accelerated phase (AP) (n=15) of CML. All enrolled patients were treated with IM 400mg/day for CP or 600 mg/day for AP as a first line TKI. Patients were monitored for cytogenetic and molecular response every 6 and 3 months respectively using conventional cytogenetic on bone marrow and quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) on peripheral blood. Results of RQ-PCR were expressed as a ratio of BCR-ABL/ABL% [IS]. Definitions of CCyR, MMR as well as CP and AP were consistent with European LeukemiaNet recommendations. The analyzed factors included: time to complete hematologic remission (CHR), time to CCyR, time to MMR and additional cytogenetic abnormalities in Ph positive cells [ACA Ph(+)] during first line IM treatment and % of CCyR and MMR during second line TKI treatment. To estimate probability of CCyR and MMR cumulative incidence analysis was used. Cytogenetic and molecular progression free survival (PFS) was estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis.

Probability of CCyR for the analyzed group was 55%, 60% and 62% after 12, 18 and 24 months of treatment with IM respectively. Probability of cytogenetic PFS was 92%, 83%, 81% and 76% in 12, 18, 24 and 36 months respectively. There was observed statistically significant correlation between probability of achievement of CCyR, MMR and the following: time to CHR, time to imatinib introduction, phase of the disease and ACA Ph(+). No correlation between probability of CCyR, MMR and age, sex, Sokal and Hasford risk factors was observed. 1) Early CHR in up to 8 weeks after diagnosis (dx) predicted CCyR and MMR achievement irrespective of treatment schedule to CHR (p<0,0001) (Fig 1.).

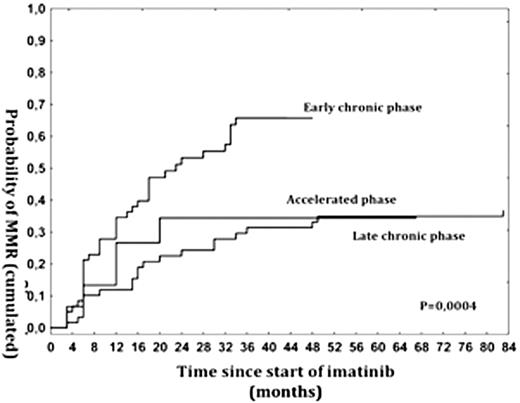

2) Early IM introduction up to 4 months since dx increased probability of CCyR and MMR in 12 and 18 months respectively (p<0,0001). 3) Patients in LCP were significantly less likely to obtain CCyR and MMR comparing to ECP and results in this group were similar to AP patients (p=0,0004) (Fig. 2).

Probability of MMR with regard to phase of the disease at the moment of IM start

4) Early CCyR up to 6 months after starting IM increased probability of MMR (p<0,0001). 5) ACA Ph(+) were confirmed as an adverse prognostic factor regarding to achieving (p=0,005) and maintaining (p=0,01) of CCyR. 6) Treatment with higher dose of IM predicted better outcome when ACA Ph(+) at diagnosis and/or at least 10% of blasts in bone marrow or peripheral blood at dx were considered as AP criteria. 7) Among patients after IM failure those treated with 2G TKI were more likely to achieve and maintain CCyR (52%) than those with escalation of IM (24%) (p=0,02).

These data suggest need of 1) therapy intensification from the very moment of diagnosis, 2) early achievement of CHR, 3) early IM introduction (<4 months from dx in analysed population), 4) the precise defining of AP with rigid criteria may result in better outcome. 5) Relative risk (Sokal and Hasford) relationship with treatment results seems to be not sufficient when IM is introduced after a long time since diagnosis. 5) Treatment switch to 2G TKI but not imatinib escalation after first line IM treatment failure is proposed to be an optimal treatment standard.

Foryciarz:Novartis: Consultancy, Honoraria; BMS: Consultancy, Honoraria. Sacha:Novartis: Consultancy, Honoraria, Research Funding; BMS: Consultancy, Honoraria, Research Funding. Florek:BMS: Research Funding; Novartis: Research Funding. Czekalska:BMS: Research Funding; Novartis: Research Funding. Zawada:Novartis: Research Funding; BMS: Research Funding. Skotnicki:Novartis: Consultancy, Honoraria, Research Funding, Speakers Bureau; BMS: Consultancy, Honoraria, Research Funding, Speakers Bureau.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal