Abstract

Abstract 1230

Poster Board I-252

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is incurable with a history of many relapses and several types of treatment. Addition of rituximab to chemotherapy (CT) has been shown to improve many outcome parameters. Since its approval for funding in Ontario in 2000, rituximab is routinely incorporated into initial therapy. Often, high-dose therapy is followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT) after 1, 2 or more relapses. Kang et al. (BMT (2007) 40, 973) investigated whether prior exposure to rituximab had any influence on a subsequent ASCT and found no differences in the outcomes analyzed. However, there has been evidence suggesting that that such prior exposure may alter the phenotype of these tumour cells so that they no longer express CD20, and thus potentially altering their behaviour.

We performed a single center retrospective review on all patients having received an ASCT at the Ottawa Hospital with an initial diagnosis of FL. They were grouped into four categories according to their prior exposure to or lack of prior exposure to rituximab and according to their pre-ASCT diagnosis, non-transformed FL (FL-NT) vs. transformed (FL-T).

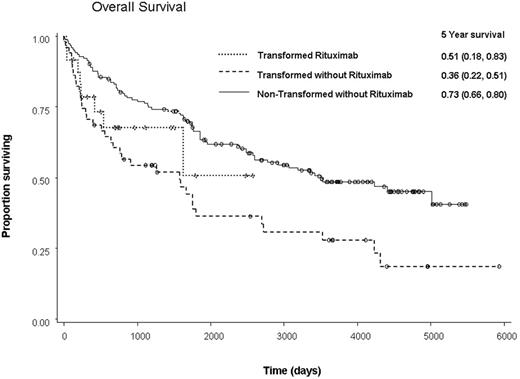

A total of 259 patients – 184 FL-NT and 75 FL-T were identified. The 5-year progression-free survivals (PFS) were 61.2% and 27.6%, respectively (p<0.0001) and the overall survivals (OS) were 72.5% and 39.3%, respectively, (p<0.0001). Within the group of FL-NT patients, 31 (17%) received rituximab and 153 were rituximab-naive. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups except in the number of CT treatments, with the rituximab-naïve group having significantly less CT than the group with rituximab exposure (p=0.0003). There were no differences in PFS or OS between FL-NT rituximab-naïve and rituximab-treated patients (5-year PFS 61% vs. 64%, p = 0.69; 5-year OS 73% vs. 68%, p=0.80). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that no other factor significantly impacted PFS while OS was negatively affected by older age (p=0.007). Within the FL-T group, 24 (32%) patients received rituximab and 51 did not. The rituximab-naïve FL-T patients had significantly less CT than those exposed to the drug (p=0.04). The subsequent 5-year PFS of the rituximab-naive vs. pre-treated groups were 22% and 55% (p =0.20), respectively, and the 5-year OS were 36% and 51% (p=0.39), respectively. Multivariate analysis for PFS demonstrated that prior exposure to rituximab had a positive effect (Hazard Ratio (HR): 0.44, 95% CI 0.20-0.97, p=0.04). Similarly, multivariate analysis for OS revealed a non-significant but positive effect (HR: 0.5, 95% CI 0.21-1.18, p=0.11). Such analyses for PFS also demonstrated that prior exposure to rituximab as well as increased time from last CT to transplant had positive effects on time to relapse (p=0.04 and p=0.03, respectively), while increased time from diagnosis to transplant (p=0.0001) had a negative impact. Multivariate analysis for OS only demonstrated that increased time from diagnosis to transplant (p=0.02) had a significant negative impact (p=0.02).

Pre-treatment with rituximab in FL-NT prior to ASCT does not adversely impact ASCT outcomes. There is a suggestion of an increase in the number of patients with FL-T being transplanted in the post-rituximab era and as expected, the FL-T had a poorer outcome than the FL-NT patients. However, prior exposure to rituximab appeared to demonstrate a trend toward an improved OS within the FL-T group (see figure). In summary, previous rituximab exposure may be associated with an increased rate of transformation, leading to the poorer outcome of patients originally diagnosed with FL-NT.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal