To the editor:

We read with great interest the recent article in Blood by Martinelli et al on rare venous thromboses.1 In the section on splanchnic vein thrombosis (SVT), it is speculated that the risk of bleeding might overweigh potential benefit from anticoagulants in patients with a high bleeding risk. We believe the definition of a “high bleeding risk” used by the authors may lead to an excessive limitation of the use of anticoagulation therapy (ACT) in these patients.

Recent studies evidence a high recanalization rate with ACT in acute portal vein thrombosis (PVT) in noncirrhotic patients. Indeed, in the study of Amitrano et al,2 ACT was effective to obtain recanalization of acute SVT in 45.4% of patients. Similarly, in a recent multicentric study involving 105 patients,3 early anticoagulation allowed a 44% recanalization rate of the portal vein at 1 year. In patients with cirrhosis, in the absence of hepatocellular carcinoma, the presence of PVT should stimulate rather than limit the use of ACT. Indeed, Francoz et al have shown that in patients with chronic liver diseases awaiting liver transplantation, the incidence of PVT reached 8.4% over a 6-year follow-up period.4 The use of anticoagulants was associated with a 42% recanalization rate of the portal vein.

High risk of bleeding in the “flow diagram for treatment of portal vein thrombosis” in the article by Martinelli et al1 is defined as the presence of esophageal varices or thrombocytopenia less than 50 000/mm3. Esophageal varices are clearly a risk factor of bleeding, particularly when they are large. It is important to note that in absence of cirrhosis, esophageal varices may result from PVT itself.5 Recanalization with ACT is the best therapy for varices, whereas thrombus extension is a recognized trigger of portal pressure increase and variceal bleeds. We believe that esophageal varices are accessible to effective therapy in the majority of cases. Ineffective medical treatment should lead to variceal band ligation, which is effective in 90% of cases.5 In the exceptional situation where ligation is ineffective, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) can be considered. In our mind, only very few patients should temporarily be kept off anticoagulants because of uncontrollable varices. A large French cohort including 84 patients with both chronic and acute PVT who received ACT over a long follow-up period6 showed no increased gastrointestinal bleeding risk and a similar severity of the hemorrhagic episodes (blood units transfused, duration of hospital stay) in patients who were treated with ACT compared with those who did not receive ACT. However, large esophageal varices were predictors of bleeding, justifying the use of a prophylactic approach (beta blockers [BBs] and endoscopic therapy). In the Francoz et al study,4 only a minor risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was associated with ACT (1 patient with a postligation ulcer).

Concerning thrombocytopenia, few data are available about a “safe” platelet count. As for varices, thrombocytopenia may be secondary to PVT alone in noncirrhotic patients. Surprisingly, a low platelet count (< 70 000/mm3) was even an independent predictor of PVT.4 In our experience, hemorrhagic episodes are infrequent in patients with PVT (with or without cirrhosis) and platelet counts greater than 30 000/mm3.

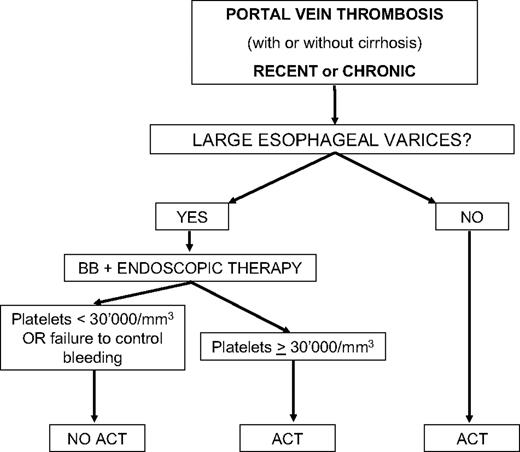

As an alternative to the algorithm proposed by Martinelli et al, which limits the use of ACT in patients with esophageal varices and low platelets, we would like to propose the scheme shown in Figure 1 that has been in use for several years in our institution for patients with PVT.

Algorithm for the use of ACT in portal vein thrombosis as followed in our institution. BB indicates beta blocker; and ACT, anticoagulation therapy.

Algorithm for the use of ACT in portal vein thrombosis as followed in our institution. BB indicates beta blocker; and ACT, anticoagulation therapy.

Authorship

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Laurent Spahr, Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Hospital of Geneva, 24, Rue Micheli-du-Crest, CH-1211 Geneva 14, Switzerland; e-mail: Laurent.spahr@hcuge.ch.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal