Abstract

Among 1153 new adult cases of peripheral/T-cell lymphoma from 1990-2002 at 22 centers in 13 countries, 136 cases (11.8%) of extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma were identified (nasal 68%, extranasal 26%, aggressive/unclassifiable 6%). The disease frequency was higher in Asian than in Western countries and in Continental Asia than in Japan. There were no differences in age, sex, ethnicity, or immunophenotypic profile between the nasal and extranasal cases, but the latter had more adverse clinical features. The median overall survival (OS) was better in nasal compared with the extranasal cases in early- (2.96 vs 0.36 years, P < .001) and late-stage disease (0.8 vs 0.28 years, P = .031). The addition of radiotherapy for early-stage nasal cases yielded survival benefit (P = .045). Among nasal cases, both the International Prognostic Index (P = .006) and Korean NK/T-cell Prognostic Index (P < .001) were prognostic. In addition, Ki67 proliferation greater than 50%, transformed tumor cells greater than 40%, elevated C-reactive protein level (CRP), anemia (< 11 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (< 150 × 109/L) predicts poorer OS for nasal disease. No histologic or clinical feature was predictive in extranasal disease. We conclude that the clinical features and treatment response of extranasal NK/T-cell lymphoma are different from of those of nasal lymphoma. However, the underlying features responsible for these differences remain to be defined.

Introduction

Mature T- or natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma makes up only 5% to 18% of all cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL),1-3 and the relative frequency and optimal therapy for these disorders is not well defined. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma is a distinct entity in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification,4 and is much more prevalent in Asian and Hispanic populations.5-7 Most cases are derived from NK cells with expression of CD56 and cytoplasmic CD3, but absence of surface CD3 expression and T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangements.8 However, some cases have a genuine clonal T-cell phenotype and genotype,9 and all cases express cytotoxic proteins such as TIA-1, granzyme B, and perforin. Histologically, the disease is characterized by local invasion and necrosis with invariable Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection of the neoplastic cells. In published series, 60% to 90% of cases are localized to the nasal and upper airway region (nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma).6,7,10 However, a similar disease can occur primarily in extranasal sites (eg, skin, testis, intestine, muscle), or as a disseminated disease without any apparent nasal involvement.11 The biologic relationship between nasal and extranasal disease remains unclear.12 Despite radiotherapy and chemotherapy, the prognosis is poor with 5-year survival rates below 30% in single center or national retrospective series.6,7,10,12-15 However, there has been no major international multicenter study of such cases with central pathology review. Herein, we present the findings for 136 cases of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project.

Methods

The International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project consists of a consortium of 22 clinical centers in 13 countries in North America, Europe, and the Far East (Appendix 1). This retrospective study included consecutive adult cases of untreated peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) or natural killer/T-cell (NK/T-cell) lymphoma (excluding mycosis fungoides /Sézary syndrome) diagnosed between 1990 and 2002. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions. The standardized clinical and histologic review process has been described.16,17 Briefly, the local pathologist reviewed the diagnostic pathology slides and reports, recorded the immunophenotypic, cytogenetic, and molecular studies, and then submitted the slides and a tissue block for regional review. Cases without tissue blocks were acceptable if the slides and immunostains or flow cytometry data were adequate. The clinical information for each case was abstracted from the medical record. Panels of 4 expert hematopathologists traveled to the regional centers: Omaha, NE (D.D.W.); Leeds, United Kingdom (K. A. MacLennen); Wurzburg, Germany (T. Ruediger); Bologna, Italy (S. Pileri); and Nagoya, Japan (S.N.) for central slide review. A standard immunostain panel was performed (CD20, CD2, CD3, CD5, CD4, CD8, CD30, CD56, TCR-β, TIA-1, Ki67, and in situ stains for Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNA [EBERs]). Using the World Health Organization (WHO) classification criteria, NK/T-cell lymphoma was diagnosed with a consensus among at least 3 of the 4 experts.16 The percentages of transformed tumor cells (blasts) and tumor cells expressing CD30 or Ki67 were also estimated. All clinical and pathologic data were centrally analyzed, presented, and discussed at a consensus conference attended by all of the investigators. For survival analysis, the International Prognostic Index (IPI; age, stage, lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] level, extranodal sites, performance status)18 and Korean prognostic model for nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma (K-PI; adverse factors: stage > 2, LDH > normal, presence of B symptoms or regional lymph nodes)7 were evaluated. The K-PI could not be evaluated for extranasal disease since complete data on regional lymph node involvement was not available. Overall survival (OS) was measured as the time from diagnosis to death from any cause, with surviving patient follow-up censored at the last contact date. Failure-free survival (FFS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to first occurrence of progression, relapse after response, or death from any cause. Estimates of OS and FFS distributions were calculated using the method of Kaplan and Meier19 and time-to-event distributions were compared using the log-rank test.20 The Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical features.

Results

Relative frequency and epidemiology

Among 1314 cases submitted for the study, 1153 cases met the inclusion criteria for peripheral T-cell lymphoma16 including 136 cases (11.8%) of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma (Table 1). These included 92 (68%) nasal and 35 (26%) extranasal cases (ratio 3:1). A small number of cases (6%) could not be classified as either nasal or extranasal types because of presentation with extensive disease (n = 2, aggressive NK-cell leukemia) or primarily as nodal disease (n = 7, unclassifiable NK-cell lymphoma). The relative frequency of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma among lymphomas in the study was higher in Asian countries than in Western countries (22% vs 5%, P < .001) (Table 1), and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma was the most common histology in each of the Asian countries (range 34%-56%) except for Japan (11%). Even after the exclusion of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL), the frequency in Japan (18%) was still lower than in continental Asia, mainly due to fewer extranasal cases in Japan. Of 129 cases with the ethnicity reported, Asian patients accounted for 80% of the nasal and 84% of the extranasal cases. However, white patients still accounted for 9% of the nasal and 13% of the extranasal cases. Only 5 Hispanic or Native North American patients were registered in the study, despite the report of an increased incidence in these ethnic groups. The remaining patients were reported to be of African ethnicity.

Study sites and number of cases of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma by site and region

| Region . | Total cases, n . | Nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, n (%) . | Extranasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, n (%) . | Aggressive NK-cell leukemia, n (%) . | Unclassifiable NK-cell lymphoma, n (%) . | All NK/T-cell cases, n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangkok, Thailand | 41 | 14 (34) | 7 (17) | 21 (51) | ||

| Hong Kong, China | 58 | 12 (21) | 5 (9) | 3 (5) | 20 (34) | |

| Singapore | 34 | 9 (27) | 8 (24) | 2 (6) | 19 (56) | |

| Seoul, Korea | 27 | 5 (19) | 6 (22) | 11 (41) | ||

| Tokyo, Japan | 32 | 4 (13) | 4 (13) | |||

| Nagoya, Japan | 54 | 9 (17) | 1 (2) | 10 (19) | ||

| Okayama, Japan | 36 | 7 (20) | 7 (19) | |||

| Fukuoka, Japan | 182 | 11 (6) | 1 (0.5) | 12 (7) | ||

| Asian total | 464 | 71 (15) | 27 (6) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1) | 104 (22) |

| Europe and North America | 689 | 21 (3) | 8 (1) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 32 (5) |

| Region . | Total cases, n . | Nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, n (%) . | Extranasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, n (%) . | Aggressive NK-cell leukemia, n (%) . | Unclassifiable NK-cell lymphoma, n (%) . | All NK/T-cell cases, n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangkok, Thailand | 41 | 14 (34) | 7 (17) | 21 (51) | ||

| Hong Kong, China | 58 | 12 (21) | 5 (9) | 3 (5) | 20 (34) | |

| Singapore | 34 | 9 (27) | 8 (24) | 2 (6) | 19 (56) | |

| Seoul, Korea | 27 | 5 (19) | 6 (22) | 11 (41) | ||

| Tokyo, Japan | 32 | 4 (13) | 4 (13) | |||

| Nagoya, Japan | 54 | 9 (17) | 1 (2) | 10 (19) | ||

| Okayama, Japan | 36 | 7 (20) | 7 (19) | |||

| Fukuoka, Japan | 182 | 11 (6) | 1 (0.5) | 12 (7) | ||

| Asian total | 464 | 71 (15) | 27 (6) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1) | 104 (22) |

| Europe and North America | 689 | 21 (3) | 8 (1) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 32 (5) |

Among 8 Asian centers, HTLV-1 was endemic only in Fukuoka, Japan.

Clinical presentation

Among all 136 patients, the median age was 49 years with a male-to-female ratio of 2:1 (Table 2). For both nasal and extranasal disease, the presenting symptoms were local in nature (eg, mass, ulcer, bleeding, or pain), and varied according to the site. For the 35 primary extranasal cases, the sites of involvement (including multiple sites) were the intestine (37%), skin (26%), testis (17%), lung (14%), eye or soft tissue (9% each), adrenal gland or brain (6% each), and breast or tongue (3% each). Patients with extranasal disease had more adverse clinical features such as a high stage (P < .001), elevated LDH (P = .009), bulky disease (P = .026), and poor performance status (P < .001). Extranasal cases were also more likely to have anemia and thrombocytopenia, but there were no significant differences in bone marrow involvement or hemophagocytosis. The 9 patients with aggressive or unclassifiable disease were younger and had even more adverse clinical features, but the small number of cases precluded statistical evaluation.

Differences in the clinical features of nasal and extranasal NK/T-cell lymphoma

| Clinical features . | Nasal . | Extranasal . | P (nasal vs extranasal) . | Aggressive/unclassifiable . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 92 | 35 | 9 | |

| Median age, y (range) | 52 (21-89) | 45 (19-86) | .67 | 32 (21-71) |

| Male, % | 64 | 66 | 1.0 | 78 |

| Stage III/IV, % | 27 | 68 | < .001 | 57 |

| B symptoms, % | 39 | 54 | .161 | 78 |

| Nonambulatory, % | 9 | 37 | < .001 | 56 |

| Mass > 5 cm, % | 12 | 68 | .026 | 22 |

| Extranodal sites > 2, % | 16 | 55 | < .001 | 47 |

| Bone marrow +, % | 10 | 14 | .53 | 89 |

| Hb < 11 g/dL, % | 25 | 42 | .11 | 63 |

| Platelets < 150 × 109/L, % | 12 | 25 | .09 | 70 |

| CRP > normal, % | 51 | 38 | .31 | 37 |

| LDH > normal, % | 45 | 60 | .009 | 57 |

| Hemophagocytosis, % | 3 | 3 | 1.0 | 11 |

| Clinical features . | Nasal . | Extranasal . | P (nasal vs extranasal) . | Aggressive/unclassifiable . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 92 | 35 | 9 | |

| Median age, y (range) | 52 (21-89) | 45 (19-86) | .67 | 32 (21-71) |

| Male, % | 64 | 66 | 1.0 | 78 |

| Stage III/IV, % | 27 | 68 | < .001 | 57 |

| B symptoms, % | 39 | 54 | .161 | 78 |

| Nonambulatory, % | 9 | 37 | < .001 | 56 |

| Mass > 5 cm, % | 12 | 68 | .026 | 22 |

| Extranodal sites > 2, % | 16 | 55 | < .001 | 47 |

| Bone marrow +, % | 10 | 14 | .53 | 89 |

| Hb < 11 g/dL, % | 25 | 42 | .11 | 63 |

| Platelets < 150 × 109/L, % | 12 | 25 | .09 | 70 |

| CRP > normal, % | 51 | 38 | .31 | 37 |

| LDH > normal, % | 45 | 60 | .009 | 57 |

| Hemophagocytosis, % | 3 | 3 | 1.0 | 11 |

Hb indicates hemoglobin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; and CRP, C-reactive protein.

Immunophenotype and genotype

There were no significant differences in the immunophenotypic or genotypic profiles between the nasal and extranasal cases, except for a higher percentage of expression of CD30 in extranasal cases (Table 3). Expression of EBERs was an obligatory inclusion criterion for NK/T-cell lymphoma. CD56 was expressed in most of the cases, and cytotoxic molecules (TIA1, granzyme B) were highly expressed. The more specific T-cell markers such as CD4, CD5, and CD8 were usually absent. CD2 and CD3ϵ were usually expressed but expression of TCR-β F1 was low. Interestingly, clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor (TCR) genes (either TCR-β by Southern blot analysis or TCR-γ by polymerase chain reaction) was found in 38% of the nasal cases and 27% of the extranasal cases.

Immunophenotype and genotype results in nasal and extranasal NK/T-cell lymphoma

| Immunostain/molecular test . | Nasal, % positive . | Extranasal, % positive . | Total tested cases . |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIA-1 | 95 | 94 | 107 |

| Granzyme B | 82 | 78 | 42 |

| CD56 | 81 | 89 | 121 |

| TCR-β F1 | 3 | 0 | 105 |

| CD3ϵ | 76 | 71 | 123 |

| CD30 | 39 | 63 | 110 |

| CD2 | 81 | 82 | 117 |

| CD5 | 5 | 0 | 118 |

| CD4 | 1 | 0 | 116 |

| CD8 | 14 | 14 | 116 |

| TCR-γ PCR /TCR-β SA | 38 | 27 | 52 |

| Immunostain/molecular test . | Nasal, % positive . | Extranasal, % positive . | Total tested cases . |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIA-1 | 95 | 94 | 107 |

| Granzyme B | 82 | 78 | 42 |

| CD56 | 81 | 89 | 121 |

| TCR-β F1 | 3 | 0 | 105 |

| CD3ϵ | 76 | 71 | 123 |

| CD30 | 39 | 63 | 110 |

| CD2 | 81 | 82 | 117 |

| CD5 | 5 | 0 | 118 |

| CD4 | 1 | 0 | 116 |

| CD8 | 14 | 14 | 116 |

| TCR-γ PCR /TCR-β SA | 38 | 27 | 52 |

TCR indicates T-cell receptor; RA, rearrangement; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; and SA, Southern blot analysis.

Treatment and response

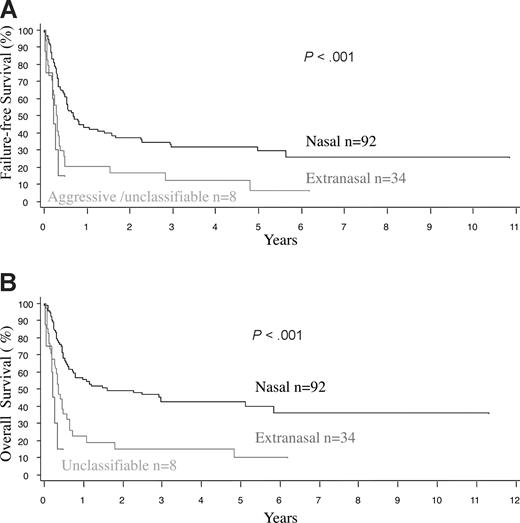

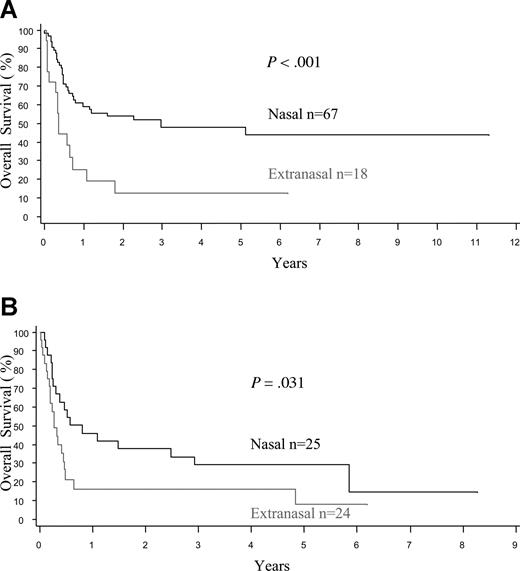

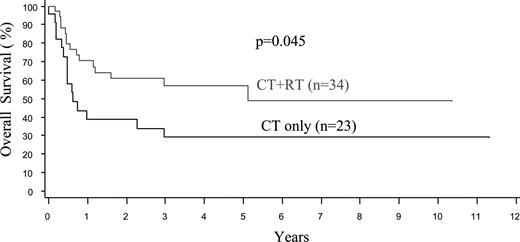

The treatment protocols were varied in this multicenter retrospective study, and treatment details were available in 91 nasal and 31 extranasal cases (Table 4). Due to advanced disease, 19% of the patients with extranasal lymphoma, but only 2% of those with nasal disease, were not treated (P < .001). Both anthracycline-based chemotherapy and radiotherapy (RT) were used more frequently in patients with nasal disease, due to a better clinical condition and more often localized disease. Less than 10% of the cases received stem cell transplantation. Taking these factors into account, the median OS and FFS for the entire cohort were only 0.65 and 0.48 years (7.8 and 5.8 months), respectively, being the worst survival among all of the PTCL categories in the project.16 The FFS and OS curves were similar at one year since most relapses were not salvageable (Figure 1A,B). The median OS was inferior for patients with extranasal compared with nasal disease (0.36 vs 1.6 years, P < .001), and for both stage I/II (0.36 vs 2.96 years, P < .001) and stage III/IV disease (0.28 vs 0.8 years, P = .031; Figure 2A,B). Survival was dismal for those with aggressive/unclassifiable disease, similar to those with extranasal disease (Figure 1A,B). Survival beyond 1 year was uncommon except for those with early-stage nasal disease and, for this group, the inclusion of RT appeared to yield a survival benefit (P = .045) (Figure 3). With combined RT and anthracycline-based chemotherapy (best conventional treatment), the OS of this subgroup was estimated at 57% at 3 years, and a plateau in the survival curve suggests that most of these patients were cured.

Treatment and outcome in nasal and extranasal NK/T-cell lymphoma

| Clinical features . | Nasal, % . | Extranasal, % . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients treated | 98 | 81 | .0009 |

| Anthracycline used | 89 | 76 | .08 |

| Radiotherapy alone vs radiotherapy and chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone | 9 vs 43 vs 48 | 12 vs 12 vs 76 | .018 |

| CR/CRu achieved | 50 | 26 | .04 |

| Disease relapse | 56 | 67 | .37 |

| HSCT performed | 9.6 | 7.1 | .70 |

| Patients dead | 55 | 88 | .0007 |

| Clinical features . | Nasal, % . | Extranasal, % . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients treated | 98 | 81 | .0009 |

| Anthracycline used | 89 | 76 | .08 |

| Radiotherapy alone vs radiotherapy and chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone | 9 vs 43 vs 48 | 12 vs 12 vs 76 | .018 |

| CR/CRu achieved | 50 | 26 | .04 |

| Disease relapse | 56 | 67 | .37 |

| HSCT performed | 9.6 | 7.1 | .70 |

| Patients dead | 55 | 88 | .0007 |

CR indicates complete remission; CRu, unconfirmed complete remission; and HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (both autologous and allogeneic).

Survival of patients with primary nasal, primary extranasal, and aggressive/unclassifiable NK/T-cell lymphoma. (A) Failure-free survival. (B) Overall survival. Note that the FFS and OS curves tend to overlap, indicating a lack of prolonged survival after treatment failure.

Survival of patients with primary nasal, primary extranasal, and aggressive/unclassifiable NK/T-cell lymphoma. (A) Failure-free survival. (B) Overall survival. Note that the FFS and OS curves tend to overlap, indicating a lack of prolonged survival after treatment failure.

Overall survival of patients with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma by stage of disease. Note the significantly better OS for nasal disease compared with extranasal disease in patients with (A) limited-stage (I/II) and (B) advanced-stage (III/IV) disease.

Overall survival of patients with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma by stage of disease. Note the significantly better OS for nasal disease compared with extranasal disease in patients with (A) limited-stage (I/II) and (B) advanced-stage (III/IV) disease.

Overall survival of patients with limited stage nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma by treatment. CT indicates chemotherapy and RT, radiotherapy.

Overall survival of patients with limited stage nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma by treatment. CT indicates chemotherapy and RT, radiotherapy.

Prognostic factors

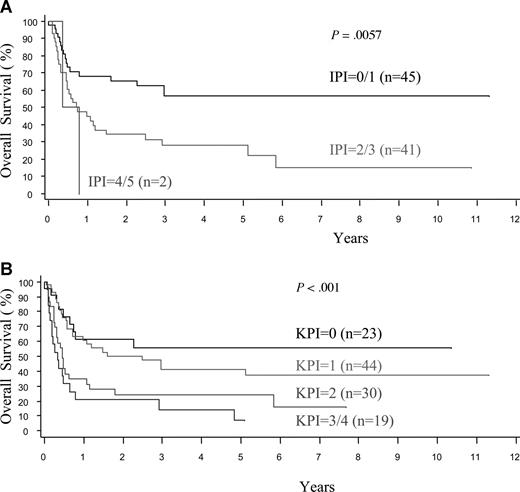

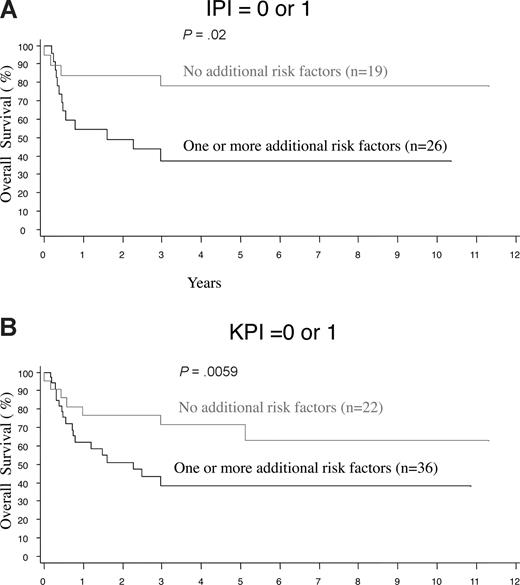

The histologic features, clinical findings, and laboratory results at the time of presentation were evaluated by univariate analyses for the prediction of survival in nasal and extranasal disease. For extranasal disease, none of the clinical and histologic features, or the IPI, had any predictive value (data not shown). For nasal disease, the OS and FFS curves are comparable and all factors significantly predictive of poor OS were also predictive of FFS, so results are only shown for OS (Table 5). Clinical features such as stage, B symptoms, the number extranodal sites, and laboratory features such as the LDH level, hemoglobin, platelet count, and C-reactive protein level (CRP; results available in only 47% of cases) were significant predictors in univariate analysis. Histologically, a high proportion of proliferating cells (Ki67 > 50%) or transformed cells (> 40%) had prognostic significance. Significant value was also confirmed for both prognostic indices, namely the IPI (P = .006) and Korean PI (P < .001; Figure 4A,B). In multivariate analysis, after controlling for the IPI or K-PI, some laboratory and histologic prognostic factors remained significant for nasal disease (Table 6). More importantly, the presence of one or more of these adverse factors appeared to further stratify the low-risk nasal cases, as defined by the IPI or K-PI (Figure 5A,B).

Univariate analysis of clinical and histologic features and prognostic indices predicting for overall survival in nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma

| Features . | P . |

|---|---|

| Stage III/IV | .053 |

| B symptoms | .042 |

| Extranodal sites > 2 | .026 |

| Hb < 11 g/dL | .0038 |

| Platelets < 150 × 109/L | .0092 |

| CRP > normal | .025 |

| LDH > normal | .0031 |

| Ki67 > 50% | .051 |

| Transformed cells > 40% | .022 |

| IPI 0,1 / 2,3 / 4,5 | .0057 |

| Korean PI 0 / 1 / 2 / 3,4 | < .001 |

| Features . | P . |

|---|---|

| Stage III/IV | .053 |

| B symptoms | .042 |

| Extranodal sites > 2 | .026 |

| Hb < 11 g/dL | .0038 |

| Platelets < 150 × 109/L | .0092 |

| CRP > normal | .025 |

| LDH > normal | .0031 |

| Ki67 > 50% | .051 |

| Transformed cells > 40% | .022 |

| IPI 0,1 / 2,3 / 4,5 | .0057 |

| Korean PI 0 / 1 / 2 / 3,4 | < .001 |

Overall survival of patients with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma according to IPI and K-PI. (A) International Prognostic Index (IPI). (B) Korean Prognostic Index (K-PI).

Overall survival of patients with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma according to IPI and K-PI. (A) International Prognostic Index (IPI). (B) Korean Prognostic Index (K-PI).

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma after controlling for the prognostic indices

| Features . | P . |

|---|---|

| Controlling for IPI | |

| Hb < 11 g/dL | .009 |

| CRP > normal | .018 |

| Transformed cells > 40% | .033 |

| Controlling for Korean PI | |

| Hb < 11 g/dL | .067 |

| Platelets < 150 × 109/L | .047 |

| Ki67 > 50% | .027 |

| Transformed cells > 40% | .017 |

| Features . | P . |

|---|---|

| Controlling for IPI | |

| Hb < 11 g/dL | .009 |

| CRP > normal | .018 |

| Transformed cells > 40% | .033 |

| Controlling for Korean PI | |

| Hb < 11 g/dL | .067 |

| Platelets < 150 × 109/L | .047 |

| Ki67 > 50% | .027 |

| Transformed cells > 40% | .017 |

Hb indicates hemoglobin; CRP, C-reactive protein; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; and IPI, International Prognostic Index.

Further stratification of low-risk nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma by the presence of clinical or histologicrisk factors. Cases were stratified by one or more of the following clinical or histologic risk factors: hemoglobin < 11 g/dL, platelets < 150 × 109/L, transformed cells > 40%, or Ki67 > 50%, after applying the (A) International Prognostic Index (IPI) or (B) Korean Prognostic Index (K-PI).

Further stratification of low-risk nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma by the presence of clinical or histologicrisk factors. Cases were stratified by one or more of the following clinical or histologic risk factors: hemoglobin < 11 g/dL, platelets < 150 × 109/L, transformed cells > 40%, or Ki67 > 50%, after applying the (A) International Prognostic Index (IPI) or (B) Korean Prognostic Index (K-PI).

Discussion

This is the first multinational retrospective study of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Compared with other published series from single centers, the median age (49 vs a range of 44-52 years) and gender ratio (2.0 vs a range of 1.5-4.2) of our cases is representative.6,7,10,13-15 The ratio of nasal to extranasal cases (2.6:1), however, is lower than that in other published series (range 2.8-8.6).6,7,10,13 This may be due to the exclusion of some less bulky nasal cases with limited diagnostic samples from our study. Referral bias is also important since nasal and cutaneous disease may be referred initially to otolaryngology or dermatology centers,21,22 and the diagnostic material may not be kept after review at the tertiary oncology center. This may also explain the lower incidence of extranasal disease in Japan, which is discordant with previous retrospective series.6,23 Although the study was not designed as a comprehensive international epidemiologic survey, the data are sufficient to confirm the high proportion of the extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma in Asian countries2,12 and the low, but significant, occurrence in the white population.

Compared with NK/T-cell lymphoma of nasal origin, the clinical and histologic features of extranasal disease are less well defined.7,11,14,24 There are few studies in which the clinical and pathologic features of nasal and extranasal disease have been studied in parallel and compared.12 Similar to published data, our extranasal cases had more adverse clinical features and the survival was poor, even in cases with apparently localized disease.25 The aggressive clinical behavior of primary extranasal disease is similar to that of stage III/IV nasal disease. The same adverse clinical features were also seen in the group of “aggressive” or unclassifiable “nodal”26 cases in our study. However, such anatomical distinctions may be arbitrary since there are reports of occult nasal disease in patients with “primary” extranasal lymphoma.27,28 Furthermore, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) staining and molecular methods can detect occult bone marrow or nasal disease in localized cases of primary nasal and extranasal lymphoma, respectively.29-32 With better staging techniques (eg, PET scans)33 and assessment of overall disease burden (eg, circulating EBV DNA),34 it is possible that these anatomical distinctions may just represent an overlapping spectrum of the same disease.

This study also allowed a definitive parallel analysis of immunophenotyping and genotyping in a large collection of nasal and extranasal cases with central pathology review. Some degree of variability in antigen expression and cytologic appearance in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma is well recognized.35 Although all cases fulfilled the WHO criteria of EBV infection and cytotoxic molecule expression, 20% to 30% of cases can have aberrant features such as being CD56 or CD3ϵ negative, or having a clonal TCR gene rearrangement.36,37 However, there is no evidence that these aberrant features affect the clinical behavior of the disease. Furthermore, we did not find any difference in the pattern of antigen expression or TCR gene rearrangement between nasal and extranasal disease. The biologic distinction, if any, between these 2 histologically similar, but prognostically different, subgroups will have to rely on future studies with genetic and epigenetic profiling.32,38

Conventional chemotherapy regimens for extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma do not differ for nasal and extranasal disease, and our retrospective multicenter study did not aim to compare different treatment modalities. However, we were able to show the importance of radiotherapy (RT) for localized nasal disease.39-41 Extranasal disease, however, appears to be less amenable to conventional RT. Dismal survival was found for patients with advanced-stage nasal disease, and those with extranasal disease irrespective of the stage. For patients in these categories, new treatments are clearly needed. It has been suggested that autologous42-44 or allogeneic stem cell therapy45,46 may provide a survival benefit for patients with extranasal or advanced nasal disease. Other nonanthracycline drugs (eg, methotrexate, l-asparaginase) are currently under investigation, and may warrant upfront use in extranasal and advanced nasal disease.47-49

Several studies have investigated the utility of the International Prognostic Index (IPI) in nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma.7,12,15 Although the IPI, which was derived from the study of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, has been used in other B- and T-cell entities, specifically designed models for specific disease entities may have better predictive value.7,50 For nasal disease, our data verified the prognostic value of the disease-specific Korean PI (K-PI), and this model may be further improved by other laboratory studies (eg, hemoglobin, platelet count) and pathologic data (eg, Ki67 proliferation, transformed cells).51 Importantly, the prognostic value of expert hematopathology review was demonstrated for the first time in this disease entity. For extranasal disease, however, the clinical outcome was poor for all prognostic subgroups. Hence, primary extranasal disease per se should lead to consideration of novel therapies. It will be interesting to see if our findings regarding these prognostic models are replicated in ongoing prospective multinational trials of novel treatments for extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma.49

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Martin Bast and Frederick Ullrich for the data collection and analysis, and Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, for the donation of the use of a Ventana XT immunostainer for the project.

Authorship

Contribution: W.-y.A., D.D.W., and R.L. wrote the paper; D.D.W., J.V., and J.O.A. designed the study; W.-y.A., D.D.W., T.I., S.N., W.-S.K., I.S., J.V., J.O.A., and R.L. contributed cases and analyzed data; and D.D.W., S.N., and I.S. performed pathologic review.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the participating institutions of the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project appears in Appendix S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Correspondence: Raymond Liang, Department of Medicine, 4/F Professorial Block, Queen Mary Hospital, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China; e-mail: rliang@hkucc.hku.hk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal