The serpin α2-antiplasmin (SERPINF2) is the principal inhibitor of plasmin and inhibits fibrinolysis. Accordingly, α2-antiplasmin deficiency in humans results in uncontrolled fibrinolysis and a bleeding disorder. α2-antiplasmin is an unusual serpin, in that it contains extensive N- and C-terminal sequences flanking the serpin domain. The N-terminal sequence is crosslinked to fibrin by factor XIIIa, whereas the C-terminal region mediates the initial interaction with plasmin. To understand how this may happen, we have determined the 2.65Å X-ray crystal structure of an N-terminal truncated murine α2-antiplasmin. The structure reveals that part of the C-terminal sequence is tightly associated with the body of the serpin. This would be anticipated to position the flexible plasmin-binding portion of the C-terminus in close proximity to the serpin Reactive Center Loop where it may act as a template to accelerate serpin/protease interactions.

Introduction

Vertebrate vascular integrity is protected by a sophisticated hemostatic mechanism that, when activated by trauma, leads to the formation of a fibrin-rich clot. Simultaneously the fibrinolytic system is activated to begin the process of remodelling and removing the clot during tissue repair.1 Fibrinolysis is initiated by trace quantities of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) derived from endothelial cells. In the presence of fibrin, tPA cleaves the protease plasminogen (which comprises an apple domain, 5 kringle domains [K1-K5], and a C-terminal serine protease domain2 ) between the fifth kringle domain and the protease domain to form plasmin, which mediates clot lysis.3 All 6 domains of plasmin remain associated via a disulphide bond after cleavage.4 The physiologic inhibitor of plasmin (ka 3.8 × 107 M−1s−1)5 is α2-antiplasmin and patients deficient in this serpin suffer a variable, but often severe, bleeding disorder.6,7 By contrast, mice with a targeted deletion of α2-antiplasmin have a normal hemostatic response to minor trauma, presumably because the deficient animals plasma contained significant residual plasmin inhibitory activity.8 However, when challenged with artificially induced pulmonary emboli, the deficient mice have a greater survival rate than the wild type (41.7% mortality vs 68.8%) consistent with up-regulation of the fibrinolytic system.9 These data suggest that therapeutic intervention in the plasmin/α2-antiplasmin interaction may be of benefit to patients with thrombotic disorders

α2-antiplasmin contains extensive N- and C-terminal sequences that flank the serpin domain (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The N-terminal sequence is crosslinked to fibrin by factor XIIIa.10 The 55 amino acid C-terminal sequence binds to the K1 and K4 domains of plasmin most strongly (K2 and K5 with lower affinity)8,11 and enhances the rate of interaction between plasmin and α2-antiplasmin by 30- to 60-fold.5 It is suggested that the C-terminus acts as a template for the interaction with plasmin, bringing its active site into apposition with the serpin reactive site.8

To understand the role of α2-antiplasmin in regulating fibrinolysis and the function of the C-terminus we report the X-ray crystal structure of an N-terminally truncated recombinant murine α2-antiplasmin.

Methods

Murine α2-antiplasmin cDNA was amplified by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from murine liver and inserted into a pET(3a)His vector.12 Recombinant murine α2-antiplasmin lacking the first 43 amino acids (α2-antiplasminΔ43) of the mature sequence was expressed in BL21(DE3) cells and purified on a HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Rydalmere, Australia), followed by a Mono Q column (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) and size exclusion chromatography.

All kinetic assays were done in triplicate in 20mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% Tween-80. The stoichiometry of inhibition (SI) was determined by incubating 5nM human plasmin (Haematologic Technologies, Essex Junction, VT) with different amounts (1–7 nM) of serpin for 2 hours at 37°C. Residual activity was assayed with 150 μM chromogenic substrate S-2251 (Chromogenix, Milan, Italy).

The second-order rate constant for plasmin inhibition by α2-antiplasminΔ43 was determined under pseudo–first-order conditions using a continuous assay.13 α2-antiplasminΔ43 (0.5nM) was reacted with human plasmin (2.5–6 nM) in the presence of 1 mM S-2251 at 25°C.

α2-antiplasminΔ43 at 5 mg/mL in a 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 25 mM NaCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol buffer crystallised in 20% PEG3350, 0.2M MgSO4 and 3% sucrose, 1.2% inositol at 22°C. The crystals diffracted to 2.65 Å resolution (Table 1). These data were processed using MOSFLM14 and SCALA.14 Five percent of the dataset was flagged for calculation of the Rfree with neither a sigma, nor a low-resolution cut-off applied to the data. Crystallographic analyses were performed using CCP4i.14

Data collection and refinement statistics

| . | Mouse α2-antiplasminΔ43 . |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P65 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c, Å | 115.70, 115.70, 100.53 |

| α, β, γ, ° | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 |

| Molecules in the asymmetric unit, no. | 1 |

| Resolution, Å | 44.95(2.65) * |

| Rpim, % | 5.9 (38.1) |

| I/σI | 15.4(2.1) |

| Total number of observations | 158236 (20909) |

| Total number of unique reflections | 22284 |

| Completeness, % | 99.9(99.7) |

| Multiplicity | 7.1(6.5) |

| Refinement | |

| Rwork / Rfree, % | 18.31 / 21.52 |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 2845 |

| Water | 82 |

| B-factors, Å2 | |

| Protein | 23.7 |

| Water | 36.17 |

| RMS deviations | |

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.008 |

| Bond angles, ° | 1.257 |

| . | Mouse α2-antiplasminΔ43 . |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P65 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c, Å | 115.70, 115.70, 100.53 |

| α, β, γ, ° | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 |

| Molecules in the asymmetric unit, no. | 1 |

| Resolution, Å | 44.95(2.65) * |

| Rpim, % | 5.9 (38.1) |

| I/σI | 15.4(2.1) |

| Total number of observations | 158236 (20909) |

| Total number of unique reflections | 22284 |

| Completeness, % | 99.9(99.7) |

| Multiplicity | 7.1(6.5) |

| Refinement | |

| Rwork / Rfree, % | 18.31 / 21.52 |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 2845 |

| Water | 82 |

| B-factors, Å2 | |

| Protein | 23.7 |

| Water | 36.17 |

| RMS deviations | |

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.008 |

| Bond angles, ° | 1.257 |

RMS indicates root mean square.

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

The structure was solved using molecular replacement (using 1YXA12 as a search probe) and the program PHASER.15 Refinement was performed using CNS16 and REFMAC14 (with Translation and Liberation Screw refinement) and a bulk solvent correction (Babinet model with mask). Model building was carried out using COOT. Water molecules were added using ARP/wARP when the Rfree reached 30%.

Results and discussion

Murine α2-antiplasminΔ43 is an effective inhibitor of human plasmin (ka 4.01 ± 0.20 × 106 M−1s−1, SI of 1.02 ± 0.05); these data show that the serpin is functional and properly folded. The 2.65 Å structure of α2-antiplasminΔ43 consists of residues 46 to 367 and 377 to 419 (Figure S1), and 83 water molecules. Eleven amino acids at the N-terminus (including the hexahistidine tag), residues 368 to 376 of the reactive center loop (RCL) and residues 420 to 464 of the C-terminus could not be built into electron density.

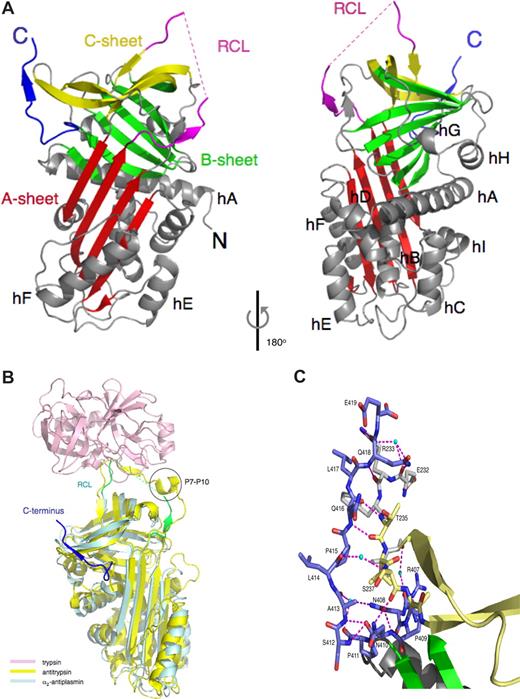

Murine α2-antiplasminΔ43 adopts the native serpin fold (Figure 1A). The 20 amino acid RCL is responsible for the initial interaction with plasmin. This region is slightly shorter than in most inhibitory serpins (24 residues in antithrombin and 21 residues in heparin cofactor II)17 and, in contrast to other serpins with longer RCLs,12,18,–20 is fully expelled from the A β-sheet. The N-terminal portion of the RCL (363–365) is tightly packed against the serpin body and forms a parallel β strand interaction with residues 214 to 216 of the s3A/s4C loop (Figure 1A). A structural comparison of α2-antiplasminΔ43 with the antitrypsin/trypsin Michaelis complex21 reveals that the α2-antiplasmin RCL may be too short to form significant interactions with plasmin outside the active site. In contrast, the P7-P10 region of antitrypsin forms a short α-helix that interacts with a trypsin exosite (Figure 1B).

The X-ray crystal structure of murine α2-antiplasminΔ43. (A) Cartoon representation of α2-antiplasminΔ43, with the A-sheet in red, the B-sheet in green, and the C-sheet in yellow, the RCL in magenta (missing residues in dotted line), the 9 helices (labeled) and loops in gray. The C-terminal region is in blue. The N and C termini are labeled. (B) Superposition of α2-antiplasminΔ43 (cyan) and the antitrypsin/trypsin Michaelis complex (1OPH)21 yellow and pink, the RCL of α2-antiplasminΔ43 in green and C-terminal extension in blue, P7-P10 of antitrypsin circled. Figures are produced with PyMOL (Delano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA). (C) A close-up view of molecular contacts between the C-terminal region and the serpin molecule. A total of 10 hydrogen bonds (magenta dashed lines; 3 of which are water mediated) are made between the C-terminus and the body of the serpin. Water molecules are cyan spheres. Colouring scheme for the residues are as in panel A, and they are labeled with the single letter code.

The X-ray crystal structure of murine α2-antiplasminΔ43. (A) Cartoon representation of α2-antiplasminΔ43, with the A-sheet in red, the B-sheet in green, and the C-sheet in yellow, the RCL in magenta (missing residues in dotted line), the 9 helices (labeled) and loops in gray. The C-terminal region is in blue. The N and C termini are labeled. (B) Superposition of α2-antiplasminΔ43 (cyan) and the antitrypsin/trypsin Michaelis complex (1OPH)21 yellow and pink, the RCL of α2-antiplasminΔ43 in green and C-terminal extension in blue, P7-P10 of antitrypsin circled. Figures are produced with PyMOL (Delano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA). (C) A close-up view of molecular contacts between the C-terminal region and the serpin molecule. A total of 10 hydrogen bonds (magenta dashed lines; 3 of which are water mediated) are made between the C-terminus and the body of the serpin. Water molecules are cyan spheres. Colouring scheme for the residues are as in panel A, and they are labeled with the single letter code.

The C-terminal portion of the RCL joins onto the first strand (s1C) of the C-sheet. In α2-antiplasmin, a conservative mutation in s1C of a buried hydrophobic residue (Val384Met) results in a bleeding disorder.7 Mutations in this region in other serpins result in reduced inhibitory activity through misfolding, disruption of the conformation of the RCL or by promoting serpin polymerization.22

α2-antiplasmin is one of 2 known F-clade serpins.17 The other member of this clade, SERPINF1, is a noninhibitory serpin that possesses potent anti-angiogenic activity.23 The role of α2-antiplasmin in angiogenesis remains to be investigated, however, the potential for the C-terminal sequence to interact with integrins24 may point to a role for this molecule outside hemostasis.

The C-terminal sequence of α2-antiplasmin interacts with the kringle domains of plasmin and facilitates formation of the α2-antiplasmin/plasmin complex. Accordingly, a form of α2-antiplasmin lacking the extended C-terminus reacts much more slowly with plasmin.25 Our structural studies reveal that the first 10 amino acids of the C-terminus (410–419) of α2-antiplasminΔ43 are tightly associated with the serpin body (Figure 1A,B). A sharp kink in the C-terminus mediated by Pro411, permits residues 416 to 417 to form an additional β-strand (termed s4′C) at the beginning of strand s3C of the C β-sheet (Figure 1C). The remainder of the C-terminus (residues 420–464), which includes the known plasmin-binding residue Lys464, cannot be modeled into electron density, suggesting that this region is flexible in the absence of plasmin.

The structures of intact plasminogen or plasmin have not been reported, precluding a detailed modeling study of the α2-antiplasmin / plasmin complex. However, the structure reveals that the interactions between residues 410 to 419 of the C-terminus and the serpin body position the C-terminal sequence less than 30Å from the RCL (Figure 1A,B), where it would be in an appropriate position to bridge to plasmin.

To conclude, our data suggest that the α2-antiplasmin RCL is structured for simple substrate-like interaction with the protease, and that the C-terminal region may function as a “hook” that accelerates the interaction with plasmin into the physiologic range. Further, the structure may provide a foundation for the design of compounds to disrupt the α2-antiplasmin/plasmin interaction in thrombosis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

J.C.W. is a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia Principal Research Fellow and a Monash University Senior Logan Fellow. A.M.B. is an NHMRC Senior Research Fellow. We thank the NHMRC, the Australian Research Council and the Australian Synchrotron Research Program for support. We thank IMCA-CAT and the Advanced Photon Source for synchrotron facilities. The coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Databank (www.rcsb.org, PDB ID 2R9Y).

Authorship

Contribution: R.H.P.L. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; T.S. performed research and wrote the paper;W.T.K., C.R.H., and C.G.L. performed research; A.J.H. analyzed data; A.M.B. analyzed data and wrote the paper; and J.C.W. and P.B.C. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dr James C. Whisstock, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Monash Univer-sity, PO Box 13d, Melbourne, Victoria 3800 Australia; e-mail: James.Whisstock@med.monash.edu.au; or Dr Paul B. Coughlin, Australian Center for Blood Diseases, Level 6 Burnet Building, 89 Commercial Road, Prahrann, Victoria 3181 Australia; e-mail: Paul.Coughlin@med.monash.edu.au.

References

Author notes

R.H.P.L. and T.S. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal