Leukocyte adhesion deficiency type-1 (LAD-1) is an autosomal recessive immunodeficiency caused by mutations in the β2 integrin, CD18, that impair CD11/CD18 heterodimer surface expression and/or function. Absence of functional CD11/CD18 integrins on leukocytes, particularly neutrophils, leads to their incapacity to adhere to the endothelium and migrate to sites of infection. We studied 3 LAD-1 patients with markedly diminished neutrophil CD18 expression, each of whom had a small population of lymphocytes with normal CD18 expression (CD18+). These CD18+ lymphocytes were predominantly cytotoxic T cells, with a memory/effector phenotype. Microsatellite analyses proved patient origin of these cells. Sequencing of T-cell subsets showed that in each patient one CD18 allele had undergone further mutation. Interestingly, all 3 patients were young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Somatic reversions of inherited mutations in primary T-cell immunodeficiencies are typically associated with milder clinical phenotypes. We hypothesize that these somatic revertant CD18+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) may have altered immune regulation. The discovery of 3 cases of reversion mutations in LAD-1 at one center suggests that this may be a relatively common event in this rare disease.

Introduction

Somatic mosaicism due to site-specific reversions of inherited mutations to wild type has received much attention in the last decade.1,,,,,–7 Some of these reversions have expanded in the host, leading to speculation about possible survival advantages conferred on the cell population carrying the reverted normal sequence. The events leading to somatic mosaicism as a result of reversion of inherited mutations to normal are in principal different from germ-line mosaicism or somatic mosaicism due to de novo mutation.7 Pathologic mutations that have reverted to wild type have been considered paradigms of endogenous somatic gene therapy.5,8,–10 Unusual phenotypes have alerted investigators to this sort of mosaicism, such as a milder-than-expected disease course, progressive improvement of disease, or detection of phenotypically normal and abnormal cells. Several different mechanisms have been suggested to be responsible for these events: intragenic recombination, mitotic gene conversion, second-site mutations, DNA slippage, and site-specific reversion to normal. The “back mutation” or “repair” process is most likely random and may reflect an increased mutation rate in certain disorders or mutational hot spots.7,8,11 Somatic reversions have been described in epidermolysis bullosa, tyrosinaemia type I, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Lesch-Nyhan disease, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A, and Fanconi anemia.11,,–14 Among the primary immunodeficiencies, reversions in adenosine deaminase deficiency, X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency, and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome confer selective growth advantage on the corrected cells.1,2,4,5,9,10

Leukocyte adhesion deficiency type-1 (LAD-1) is an autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in the gene encoding CD18.15,–17 It is characterized by absent or dramatically diminished expression of the CD11/CD18 integrins or the expression of nonfunctional forms of these integrins.17,,–20 Cellular manifestations of LAD-1 include defective polymorphonuclear chemotaxis, margination, adherence, phagocytosis of complement-coated particles, and bacterial killing, as well as diminished natural killer (NK)–cell function and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) activity. Affected patients have elevated blood neutrophil counts, frequent life-threatening systemic, skin, and soft tissue infections, and severe periodontitis and gingivitis.17 Inflammatory bowel disease has been reported in several LAD-1 patients.21,22 Even though the heterogeneity of clinical phenotype has been linked to the diversity of CD18 mutations, Shaw et al found biochemical correlation between genotype and phenotype in 3 LAD-1 patients with residual CD11/CD18 expression and function.23 During routine evaluation of CD18 expression on leukocytes of 3 LAD-1 patients, we found small populations of CD18+ lymphocytes, in addition to the major CD18− populations. We subsequently identified these CD18+ populations as somatic revertants. In this report, we describe these reversion mutations in LAD-1 lymphocytes and their effects on function.

Methods

Patients were enrolled on protocol 93-I-0119 approved by the NIAID institutional review board. The entire clinical investigation was conducted and informed consent obtained from all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

Patient 1 was a white male born to nonconsanguineous parents in 1983. He had umbilical stump separation at 10 weeks and a persistently elevated white cell count since birth. The diagnosis of LAD-1 was confirmed by flow cytometric analysis. He had no matched related donors. He had Pseudomonas sepsis at 10 months of age, perioral and esophageal strictures requiring frequent mechanical dilatation, chronic gingivitis, and recurrent oral mucosal ulcers. Extensive colonic ulcerations responded to treatment for inflammatory bowel disease. Recurrent, nonhealing groin and perianal ulcers required multiple skin grafts. Matched unrelated bone marrow transplantation at age 21 years was complicated by severe graft-versus-host disease and death.

Patient 2 was a white female born to nonconsanguineous parents in 1979. At 10 days of age, she developed omphalitis. She was diagnosed with LAD-1 at 6 years.17,20,24,–26 She had subglottic abscess at 10 years, osteomyelitis of the left ankle at 14 years, and extensive colitis with perianal fistula formation at 16 years. She had extensive gingivitis and recurrent buccal cellulitis. Following removal of all permanent teeth, her gingivitis resolved at 22 years. Now 28 years old, she is doing very well.

Patient 3, a white male, was born to nonconsanguineous parents in 1971. He presented at 10 years with poor wound healing after tracheostomy for complicated croup.27,28 At 18 years, exploratory laparotomy for presumed appendicitis found what was interpreted as Crohn disease. He has had recurrent poorly healing ulcers on the legs and thighs, and severe gingivitis and periodontitis. At 28 years, he had emergency laparotomy for ileocecal stenosis, which resulted in right hemicolectomy.21 At 35, he was started on infliximab for LAD-1–associated colitis, to which he has responded very well.

Flow cytometric analysis

Peripheral blood specimens were collected into EDTA-containing tubes. Fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies were added to whole blood washed in PBS once. After staining for 30 minutes, stained samples were treated with BD fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) Lysing Solution (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) for 10 minutes to lyse erythrocytes.29 Cells were washed twice and analyzed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson) flow cytometer using Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson). Cells were labeled with monoclonal antibodies conjugated with FITC, PE, PerCP, PE-CY5, or APC. Antibodies used for staining were as follows: anti-CD3, -CD4, -CD8, -CD16, -CD18 (hybridoma C71/16), -CD11a, -CD11b, -Cd11c, -CD19, -CD27, -CD28, -CD56, -CD45/CD14 (leucogate), and -TCRαβ (Becton Dickinson); and -CD18, -CD57, and -TCRγ/δ (Immunotech, Marseille, France); irrelevant antibodies of the IgG1 and IgG2b subclasses were used to determine background staining. 10Test Beta mark (Immunotech, Marseille, France), containing mixtures of dual-color (FITC and PE) conjugated TCR Vβ antibodies, was used in combination with anti-CD18 and -CD8 antibodies.

Cell sorting and extraction of genomic DNAs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were purified from whole blood using density gradient centrifugation. Cells were stained using anti-CD3 and anti-CD18 antibodies. CD3+/CD18+ and CD3+/CD18− cells were sorted using a BD FacsVantage (Becton Dickinson). Purity analysis and cell counts were done after sorting. Genomic DNA isolation from the sorted CD3+/CD18+ and CD3+/CD18− cells was done using Gentra Puregene cell kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Microsatellite analysis

Genomic DNA isolated from the sorted CD3+/CD18+ and CD3+/CD18− cells was compared by analysis of microsatellite DNA sequences. Seven distinct microsatellite sequences were amplified by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with a multiplexed PCR kit (Ampfister Profiler; Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The PCR product was run on an automated sequencer (model 310; Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems) and analyzed with GeneScan software (ABI Prism, version 3.1; Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems). We assessed the data for unique microsatellite polymorphisms that would be indicative of hematopoietic chimerism.30

PCR amplification and cloning of mutant DNA fragments

The following primers (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used to amplify the given mutation sites: For Y131S (patient 1): sense 5′-AGC GTT CAA CGT GAC CTT CC-3′ and antisense 5′-AAT GCG GCC GGA CTC GGT GA-3′ (160-bp fragment); for G284S (patient 2): sense 5′-GAG GAA ATC GGC TGG CGC AAC G-3′ and antisense 5′-GGG GAC TTA CGA ATT CGT TGC TCC-3′ (166-bp fragment); for 741–14C>A (247 + PSSQ, patient 3): sense 5′-ACA GCT GGG TCC CTG AGA CCC AGG-3′ and antisense 5′-GTC AGT GGT GTC CTG CCA GGC GGT GC-3′ (350-bp fragment); for N351S (patient 3): sense 5′-GCG TGG AGA TGC CGT GGC ACA GG-3′ and antisense 5′-GCA GTG GGG AGA TTG CTG GCC ACC-3′ (252-bp fragment); and for R586W (polymorphisms previously reported in patient 3): sense 5′-CTC TGC TTC TGC GGG AAG TG-3′ and antisense 5′-AGA GAG GCA GCT GGT AGC CTG AAT-3′ (168-bp fragment). Amplifications were done using Platinum Taq (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Purified PCR products (QIAquick PCR Purification Kit; Qiagen) were cloned into PCR 2.1 vector (Topo TA Cloning kit; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); clones were grown, selected, and purified as per the manufacturer's instructions. Purified DNAs (vector + insert) were used for sequencing.

Sequence analysis and screening of clones

Direct sequencing of the purified DNAs was carried out to screen the clones using a Model 377 Applied Biosystems sequencer and Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequence was analyzed with Sequencher 3.1.1 software (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI).

Transfection and adhesion assays

Monoclonal antibodies used for expression analysis of transfected cells have been described previously.31,32 Mutant cDNA fragments were created using site-directed mutagenesis, cloned into pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen BV, Groningen, The Netherlands) and transfected into COS-7 cells as described.23 The monoclonal antibody 1B4, which is specific for CD11/CD18 heterodimers, was used to measure the expression of the heterodimers on COS-7 cells transfected with CD11 alone or cotransfected with either wild-type, mutant, or revertant CD18. Adhesion has been described previously.23 Briefly, microtiter wells were coated with ICAM-Fc or iC3b as described. COS-7 transfectants were resuspended in RPMI-1640 with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, and 5% fetal calf serum (RPMI-FH) to between 0.5 and 1 × 106 cells/mL. The fluorescent dye BCECF-AM (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands), at 1 μg/μL in DMSO, was added to a final concentration of 1 μg/mL, and labeling was carried out at 37°C for 20 minutes. The cells were washed twice. A 50-μL volume of the cell suspension was dispensed into each well of the ligand-coated microtiter plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The total number of cells in each well was quantified by measuring the fluorescence signal using the Cytofluor 4000 fluorescent plate reader (PE Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom). Percentage of cell adhesion was determined as the relative fluorescence signal after washing 3 times with 150 μL RPMI-FH (percentage of cell adhesion = relative fluorescence signal = fluorescence of washed [adhered] cells/unwashed cells). CD11/CD18-mediated adhesion to the various ligands was activated with the MoAb KIM185 (2.5 μg/mL); or with 1.5 mM EGTA and 5 mM MgCl2 (Mg2+/EGTA) for CD11a/CD18-mediated adhesion; or with 0.5 mM MnCl2 for CD11b/CD18 and CD11c/CD18-mediated adhesion.

CD18+ T-cell superantigen response

PBMCs from healthy controls and the 3 patients were cultured either in complete media alone, or in combination with SEB (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and IL-2 (Chiron, Emeryville, CA) for 6 days. Expansion of the CD18+ lymphocyte population was analyzed by flow cytometry using specific surface markers.

Results

Mosaicism of CD18 expression in T cells in patients with LAD-1

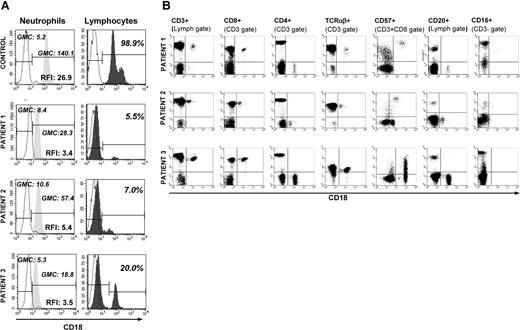

Flow cytometry were used to evaluate CD18 expression of peripheral blood polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) and lymphocytes. All 3 LAD-1 patients had single populations of PMNs with very dim CD18 staining compared with control (Figure 1A). Intensity of staining was calculated using relative fluorescence intensity (RFI), which is geometric mean channel (GMC) for CD18 divided by GMC for isotype control. RFI for patient PMNs ranged from 3.4 to 5.4 in comparison with the RFI for control PMN of 26.9. However, unlike PMNs, lymphocytes demonstrated distinct CD18+ populations in addition to the major CD18-dim peaks. In patient 1, 5.5% of the lymphocytes were CD18+, with a GMC of 100 (RFI: 15.0); in patient 2, 7% of lymphocytes were CD18+ with a GMC of 40 (RFI: 6.0); in patient 3, 20% of lymphocytes were CD18+ with a GMC of 110 (RFI: 16.2). Our healthy control range for CD18 expression in lymphocytes is 99% to 100% with a GMC range of 95 to 136 (RFI: 19–27.2). Whereas the CD18+ lymphocytes of patient 1 displayed a wide coefficient of variation (CV), patients 2 and 3 had CD18+ lymphocytes with a narrow CV. The numbers and percentages of CD18+ lymphocytes were stable over 6 to 10 determinations spanning a 5- to 10-year time frame for each patient.

Peripheral blood phenotyping. (A) Flow cytometric detection of CD18 expression of peripheral blood neutrophils and lymphocytes in 3 LAD-1 patients and a healthy control. CD18 expression is shown as histograms. For PMNs, anti-CD18 antibody binding is expressed as relative fluorescence intensity (RFI), defined as geometric mean channel (GMC) fluorescence of CD18 FITC divided by GMC fluorescence of isotype control. For lymphocytes, percentage of lymphocytes staining positive for CD18 is shown. All 3 patients have a lymphocyte population distinctly positive for CD18 compared with the rest of the lymphocyes. The solid peaks represent CD18, while dashed lines represent the isotype controls. (B) Four-color flow cytometry analysis of PBMCs from 3 patients with LAD-1. Backgating and multigating techniques were used to assess coexpression of multiple cell surface markers on CD18+ lymphocytes. CD18 is expressed on the x-axis of all dot plots, while the indicated surface antibody is shown on the y-axis. CD18 was coexpressed with CD3 and CD8 but not with CD4 or CD20. CD18+ T cells did not stain with CD27 or CD28 (data not shown). TCR staining revealed more than 95% TCRαβ+ in the CD3+/CD18+ population. Patients 1 and 2 had small populations of CD18+ cells carrying NK (CD3−/CD56+/16+) cell surface markers (1% and 5% of all CD18+ cells, respectively).

Peripheral blood phenotyping. (A) Flow cytometric detection of CD18 expression of peripheral blood neutrophils and lymphocytes in 3 LAD-1 patients and a healthy control. CD18 expression is shown as histograms. For PMNs, anti-CD18 antibody binding is expressed as relative fluorescence intensity (RFI), defined as geometric mean channel (GMC) fluorescence of CD18 FITC divided by GMC fluorescence of isotype control. For lymphocytes, percentage of lymphocytes staining positive for CD18 is shown. All 3 patients have a lymphocyte population distinctly positive for CD18 compared with the rest of the lymphocyes. The solid peaks represent CD18, while dashed lines represent the isotype controls. (B) Four-color flow cytometry analysis of PBMCs from 3 patients with LAD-1. Backgating and multigating techniques were used to assess coexpression of multiple cell surface markers on CD18+ lymphocytes. CD18 is expressed on the x-axis of all dot plots, while the indicated surface antibody is shown on the y-axis. CD18 was coexpressed with CD3 and CD8 but not with CD4 or CD20. CD18+ T cells did not stain with CD27 or CD28 (data not shown). TCR staining revealed more than 95% TCRαβ+ in the CD3+/CD18+ population. Patients 1 and 2 had small populations of CD18+ cells carrying NK (CD3−/CD56+/16+) cell surface markers (1% and 5% of all CD18+ cells, respectively).

Immunophenotyping of CD18+ cells

In all 3 patients, the majority of the CD18+ cells were also CD3+, CD8+, and CD57+ and CD4−, CD20−, CD27−, and CD28− (Figure 1B). More than 95% of the CD18+ cells were of the TCR αβ phenotype, making them memory effector/cytotoxic T cells. Only 1% and 5% of all the CD18+ cells from patients 1 and 2, respectively, carried surface markers for NK cells (CD3−/CD56+/16+). These CD3−/CD56+/CD16+ cells were not found among the CD18+ cells of patient 3.

Distribution of the alpha integrins

We compared CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c surface expression of memory effector cells among our 3 patients and healthy controls. Healthy controls express CD11a commensurate with their CD18, usually around 100%. Likewise, patients displayed CD11a expression at similar levels as their CD18 expression on their CD18+ memory effector cells (5%, 3%, and 20% in patients 1, 2, and 3, respectively). In healthy controls, CD11b and CD11c expression was less than CD18 and CD11a expression in memory effector cells (15%-35% and 1%-5%, respectively). CD11b and CD11c expression was much less than the CD11a expression: CD11b expression was 2.4%, 1.5%, and 1%, while CD11c expression was 2.5%, 1.5%, and 6.7% for patients 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Origin of CD18+ cells

Because it was possible that these cells could have been from transfusion or persistent maternal engraftment, we investigated the origin of the CD18+ lymphocyte populations in these patients. Genomic DNA extracted from sorted CD18+ and CD18− T cells was analyzed for microsatellite profiles. For each patient, evaluation of 7 polymorphic microsatellite markers showed identical patterns for the CD18+ and CD18− lymphocytes, confirming that the CD18+ cells were of patient origin (data not shown).

Molecular defects in CD18 in patients with LAD-1

Total RNA extracted from patient 1's Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) B cells was reverse transcribed and first-strand cDNA was amplified by PCR. We used the primers and nested PCR approach previously described.28 Sequencing of the amplified overlapping segments revealed that patient 1 had a novel homozygous missense mutation A>C at nt 392, resulting in Y131S (Figure 2A). We also verified this mutation by sequencing genomic DNA extracted from stored frozen PMNs of the patient, as well as from extracted genomic DNA from a paraffin-embedded skin biopsy. The same homozygous 392A>C leading to Y131S change was found in PCR-amplified genomic DNA from skin. Therefore, there was no evidence of mosaicism for this missense mutation in skin tissue and PMNs. To verify that the reversion mutation occurred in the patient and was not an inherited allele from a parent, genomic DNA was obtained from buccal epithelial cells of both parents. Both parents were heterozygous for A>C at nt 392 and the wild-type allele only. The mutations in patients 2 and 3 have been previously published.17,20,26,–28,33 Patient 2 was previously reported17,20,24,–26 as homozygous for missense G>A mutation at nt 850 resulting in G284S, a mutation reported in 2 other homozygous cases of LAD.20 To verify the absence of germ-line mosaicism in this patient, we tested genomic DNA extracted from buccal epithelial cells, which also showed homozygosity for G284S. Peripheral blood DNA from both parents was heterozygous for G>A mutation at nt 850. Nelson et al reported patient 3 as a compound heterozygote.27 His mutation A>G at nt 1052 causing N351S was not detected in either parent, indicating that this is a de novo mutation in him. The splice mutation was caused by a 12-bp insertion in the cDNA, resulting in an in-frame addition of 4 amino acids between proline 247 and glutamic acid 248 (247 + PSSQ). This splice mutation arose by C>A transversion in the 3-prime terminus of intron 6, generating an aberrant splice acceptor site (nt 741-14C>A) (Figure 2A).27 The maternal mutant allele carried the polymorphism in the cysteine-rich domain of CD18 (C>T at nt1756, leading to R586W). To demonstrate the absence of germ-line mosaicism in this patient, we used genomic DNA extracted from a skin biopsy. Pathologic mutations, leading to the previously identified compound heterozygosity in peripheral blood, were found in the skin biopsy. Therefore, all 3 patients had reversions of their mutant alleles that arose in them primarily and appear to be limited to the hematopoietic compartment.

Mutation analysis. (A) Mutations in ITGB2 patients with LAD-1. The 4 mutations in these 3 patients all affect the highly conserved I/A domain of the protein. The numbering of the mutated residues is calculated from the beginning of the signal sequence. (B) Comparison of sequences. CD3+/CD18+ and CD3+/CD18− cells from 3 LAD-1 patients were sorted and genomic DNA was extracted. Mutation sites and surrounding sequence were PCR amplified and subcloned. Clones were sequenced and compared for each patient. All of the 20 CD18+ clones screened for patient 3 had wt intronic sequence. The mutation A>G at nt 1052 was maintained (not shown).

Mutation analysis. (A) Mutations in ITGB2 patients with LAD-1. The 4 mutations in these 3 patients all affect the highly conserved I/A domain of the protein. The numbering of the mutated residues is calculated from the beginning of the signal sequence. (B) Comparison of sequences. CD3+/CD18+ and CD3+/CD18− cells from 3 LAD-1 patients were sorted and genomic DNA was extracted. Mutation sites and surrounding sequence were PCR amplified and subcloned. Clones were sequenced and compared for each patient. All of the 20 CD18+ clones screened for patient 3 had wt intronic sequence. The mutation A>G at nt 1052 was maintained (not shown).

Based on neutrophil staphylococcal killing, neutrophil adhesion to plastic and fibronectin upon stimulation, and neutrophil CD18 up-regulation in response to FMLP (data not shown), patients 1 and 2 had no residual CD18 function. We concluded that the low degree of CD18 expressed by PMNs was not permissive for function at baseline or with in vitro stimulation. Patient 3 had some baseline function, but his ability to up-regulate adhesion and neutrophil CD18 expression upon stimulation was very limited.

Four other patients with LAD-1 examined for cell surface CD18 expression did not demonstrate identifiable CD18+ subsets in their peripheral blood. Their genotypes were as follows: subjects A and B are siblings born in 1994 and 1996 with homozygous genomic deletions of approximately 1500 bases in ITGB2 spanning exons 12 and 13 (not previously reported). Subject C was born in 1981 and died of fungal sepsis at age 12 years.16,34 He was homozygous for C>A mutation at nt 1602 leading to 534X. Subject D was born in 1995 and had a compound hereozygous phenotype of G>A missense mutation at nt 850 resulting in G284S and 2142delT in exon 14 resulting in a premature truncation (not previously reported).

Reversion mutations in CD18+ lymphocyte populations

Genomic DNA was obtained from sorted CD3+/CD18+ and CD3+/CD18− lymphocytes from each of our 3 patients. Mutation site–specific amplification, subcloning, and sequencing were performed. All of the CD18− clones (10/10) from patient 1 were homozygous for A>C at nt 392 leading to Y131S (Figure 2B). In contrast, 4 of 10 CD18+ clones showed A>T at nt 392, which encodes Y131F. The remaining 6 of 10 CD18+ clones had the original missense mutation A>C at nt 392. This indicated a heterozygous forward mutation of Y131 from 131S to 131F (TCT, serine to TTT, phenylalanine). Because of the homozygosity of the inherited original mutation Y131S, neither gene conversion nor crossing over could be the mechanism.

Patient 2 was homozygous for a missense G>A mutation at nt 850, leading to G284S. When genomic DNA was extracted from her peripheral blood CD18− T cells, it was subcloned and analyzed. All 12 PCR clones carried the mutant G>A nt 850 (AGC: serine) instead of the wild-type (GGC: glycine). PCR clones derived from her CD18+ T cells, however, showed 3 different sequences. Five of 10 clones carried the original G>A nt 850 (AGC: serine), 3 of 10 clones had G>C missense mutation at nt 850, leading to arginine: CGC. Two of 10 PCR clones had a second-site mutation C>G at nt 852, in addition to the original mutation G>A at nt 850, also leading to arginine at 284 (AGG) (Figure 2B). Therefore, a subset of CD18+ T cells was phenotypically identical, all with an arginine in position 284, but using 2 different codons. Half of the CD18+ clones carried the original mutation, while the other half had changes leading to the same amino acid (arginine), which is in agreement with the hypothesis that the forward mutations took place on only 1 of the 2 alleles.

Mutations in ITGB2 from 3 patients with LAD-1

| Patient . | Original mutation, nucleotide: amino acid . | Reversion, nucleotide: amino acid . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A→C nt 392: Y131S | C→T nt 392:S131F |

| 2 | G→A nt 850: G284S | A→C nt 850: S284R and C→A nt 852A;852A;S284R |

| 3 | A→G nt 1052;N351S and C→A nt 741-14:247 + PSSQ | No reversion at nt 1052 and A→C nt 741-14 (WT) |

| Patient . | Original mutation, nucleotide: amino acid . | Reversion, nucleotide: amino acid . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A→C nt 392: Y131S | C→T nt 392:S131F |

| 2 | G→A nt 850: G284S | A→C nt 850: S284R and C→A nt 852A;852A;S284R |

| 3 | A→G nt 1052;N351S and C→A nt 741-14:247 + PSSQ | No reversion at nt 1052 and A→C nt 741-14 (WT) |

The 4 mutations in these 3 patients all affect the highly conserved I/A domain of the protein. The numbering of the mutated residues is calculated from the beginning of the signal sequence.

Patient 3 was a compound heterozygote. He had C>A mutation at nt 741-14, causing 247 + PSSQ. He also had the missense mutation A>G at nt 1052, leading to N351S. On the C>A nt 741-14 allele, he had the previously identified polymorphism C>T at nt 1756T in exon 13, leading to R586W.27 All 3 sites were analyzed for reversion. Only the splicing defect in intron 6, 741-14C>A, had undergone reversion (Figure 2B). Twenty PCR clones from his CD18+ lymphocytes covering the mutation site were sequenced, and all 20 were found to have the wild-type intronic sequence (nt 741-14C). In contrast, CD18−-derived clones yielded a mixture of wild-type (nt 741-14C) and mutant (nt 741-14C>A) sequences (11/20 mutant and 9/20 wild type), consistent with his compound heterozygosity. In addition, a mixture of wild-type and mutant sequences were found in both the CD18−- and CD18+-derived clones for A>G at nt 1052 (N351S) and C>T at nt 1756T (R586W). Therefore, the CD18+ clones were the consequence of the reversion of the 741-14C>A mutation on the 247 + PSSQ/R586W allele. Analysis of genomic DNA sequences surrounding the mutation/reversion sites for possible conserved features in all 3 patients revealed no similarities or sequence patterns known to lead to such re-version mutations.

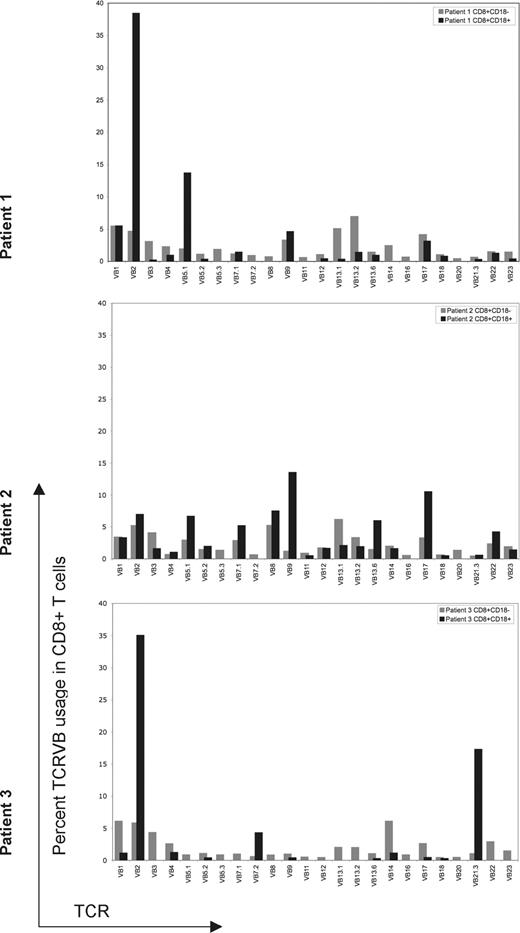

Skewed T-cell receptor distribution of revertant cells

Because the reversion occurred mostly in CD8+ T cells, we determined T-cell repertoires. The TCR Vβ repertoire of both the CD18+/CD8+ and CD18−/CD8+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry using commercially available monoclonal antibodies specific for 24 Vβ subfamilies, covering more than 70% of all TCRVβ families. The Vβ subfamilies differed between CD18+ and CD18− CD8+ T cells. In all 3 patients, all of the TCR Vβ subfamilies were expressed without underrepresentation or overrepresentation in CD18−/CD8+ cells (Figure 3). In patient 1, the CD18+/CD8+ subset did not express 7 of 24 TCR Vβ subfamilies. In patient 2, 4 of 24 TCR Vβ subfamilies were not represented in the CD18+/CD8+ cells. In patient 3, 13 of 24 Vβ subfamilies were not represented in the CD18+/CD8+ subset. Both patients 1 and 3 had overrepresentation of the TCR Vβ2 subfamily in CD18+CD8+ cells. The difference in TCR Vβ expression between the 2 populations was very pronounced in patient 3, in whom clonal rearrangement was also confirmed by PCR for (data not shown). Overall, these results indicate a differential expansion of revertant CD18+/CD8+ T cells.

Flow cytometric evaluation of 24 TCRVβ subfamilies in revertant and mutant populations. TCRVβ expression of CD18+ or CD18− CD8+ T lymphocytes for each patient was evaluated by flow cytometry, analyzed using Cellquest software and summarized using bar graphs. Gating is based on CD8+/CD18+ or CD8+/CD18− lymphocytes. CD18+ revertant T cells are represented by black bars; CD18− T cells are represented by gray bars. TCRVβ subset was considered not expressed if it was detected in less than 0.1% of the gated population. For all 3 patients, revertant cells expressed fewer TCR Vβ subsets compared with CD18− T cells. Skewing of TCVβ subfamilies is most prominent in patient 3.

Flow cytometric evaluation of 24 TCRVβ subfamilies in revertant and mutant populations. TCRVβ expression of CD18+ or CD18− CD8+ T lymphocytes for each patient was evaluated by flow cytometry, analyzed using Cellquest software and summarized using bar graphs. Gating is based on CD8+/CD18+ or CD8+/CD18− lymphocytes. CD18+ revertant T cells are represented by black bars; CD18− T cells are represented by gray bars. TCRVβ subset was considered not expressed if it was detected in less than 0.1% of the gated population. For all 3 patients, revertant cells expressed fewer TCR Vβ subsets compared with CD18− T cells. Skewing of TCVβ subfamilies is most prominent in patient 3.

CD18+ T-cell superantigen response

The differential Vβ expansion in the CD18+ T cells compared with CD18− T cells suggested the possibility of antigenic selection and peripheral expansion. To address this possibility, unselected PBMCs from the 3 patients and 2 healthy controls were cultured with either Staphylococcal enterotoxin-B (SEB) and IL-2 or media alone for 6 days. Cells were analyzed for their CD18 expression by flow cytometry. Expansion of CD18+ cells, determined by fold increase in CD18+ expression following stimulation with SEB and IL-2 as opposed to media alone, was 7.6-, 5.6-, and 3.1-fold for the 3 LAD-1 patients. Since CD18 is constitutively expressed by all lymphocytes in healthy controls and more than 95% of control cells were already CD18+ in media alone, no significant change was observed for control cells. Based on this favorable expansion of CD18+ revertant cells from 3 patients, we concluded that the reverted CD18 molecules supported proliferation to superantigen (SEB) and IL-2 better than the mutated CD18 (data not shown).

Functional evaluation of the reversion mutations

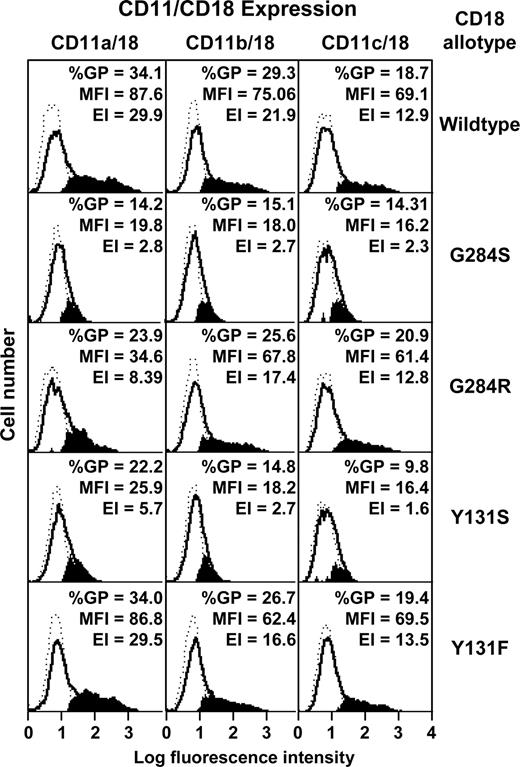

The 2 missense mutations (Y131S and G284S) and their corresponding revertants (Y131F and G284R) were created by site-directed mutagenesis and each separately introduced into CD18 cDNA in the expression vector pcDNA3, as previously described.23 Each construct was transfected into COS-7 cells together with the cDNA for either CD11a, CD11b, or CD11c, also expressed in pcDNA3.

Transfectants were analyzed for expression of CD11/CD18 heterodimers by flow cytometry with the heterodimer-specific monoclonal antibody 1B423 (Figure 4). Neither Y131S nor G284S CD18 mutants supported CD11/CD18 coexpression. However, the revertant Y131F supported full CD11a-c/CD18 coexpression. The revertant G284R also supported CD11b/CD18 and CD11c/CD18 coexpression, but expression of CD11a/CD18 was significantly lower than that of the wild type.

Transfection of wild-type and mutant CD11/CD18 dimers into COS-7 cells. Wild-type CD18 cDNA or the mutants G284S, G284R, Y131S, and Y131F were transfected into COS-7 cells together with the wild-type cDNA for CD11a, CD11b, or CD11c. CD11/CD18 expression was monitored by flow cytometry using the monoclonal antibody 1B4. The background histograms (broken lines) were obtained using an irrelevant isotype-matched antibody. Expression profiles of CD11/CD18 transfectants are shown as solid lines. The subtracted profiles (using Cellquest software) are shown in solid black. The percentage of gated positive cells (%GP), mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), and expression index (EI), derived from %GP × MFI are also shown.

Transfection of wild-type and mutant CD11/CD18 dimers into COS-7 cells. Wild-type CD18 cDNA or the mutants G284S, G284R, Y131S, and Y131F were transfected into COS-7 cells together with the wild-type cDNA for CD11a, CD11b, or CD11c. CD11/CD18 expression was monitored by flow cytometry using the monoclonal antibody 1B4. The background histograms (broken lines) were obtained using an irrelevant isotype-matched antibody. Expression profiles of CD11/CD18 transfectants are shown as solid lines. The subtracted profiles (using Cellquest software) are shown in solid black. The percentage of gated positive cells (%GP), mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), and expression index (EI), derived from %GP × MFI are also shown.

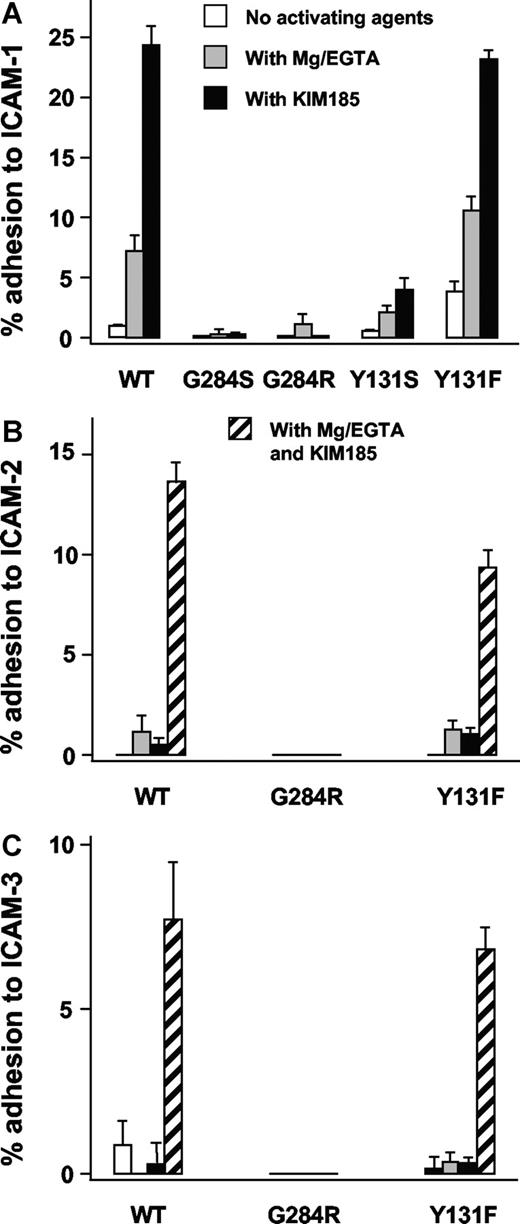

Specific adhesion to ICAM-1 ligand–coated plates was performed using the same COS-7 cells cotransfected with mutant or revertant CD18 cDNA together with CD11a cDNA. Experiments were carried out in the presence of Mg2+/EGTA or KIM185, a CD11/CD18 activating antibody. LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18)–mediated binding of COS-7 cells carrying the mutants Y131S or G284S to ICAM-1–coated plates was negligible. In contrast, COS-7 cells carrying the wild-type CD18 along with CD11a showed adhesion with Mg2+/EGTA and with KIM185. Binding of the revertant Y131F to ICAM-1 was activated to wild-type levels with Mg2+/EGTA or KIM185 (Figure 5A). The revertant G284R did not bind to ICAM-1.

Adhesion of LFA-1 transfectants. Adhesion of LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18) transfectants to ICAM-1 (A), ICAM-2 (B), and ICAM-3 (C). Adhesion was done in the absence of activating agents, in the presence of 1.5 mM EGTA and 5 mM MgCl2 (Mg/EGTA), or with the activating monoclonal antibody KIM185 (2.5 μg/mL) or with both Mg/EGTA and KIM185 (for ICAM-2 and ICAM-3 only). CD18-independent adhesion (background) was determined by inhibition with monoclonal antibody 1B4 (10 μg/mL) and has been subtracted.

Adhesion of LFA-1 transfectants. Adhesion of LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18) transfectants to ICAM-1 (A), ICAM-2 (B), and ICAM-3 (C). Adhesion was done in the absence of activating agents, in the presence of 1.5 mM EGTA and 5 mM MgCl2 (Mg/EGTA), or with the activating monoclonal antibody KIM185 (2.5 μg/mL) or with both Mg/EGTA and KIM185 (for ICAM-2 and ICAM-3 only). CD18-independent adhesion (background) was determined by inhibition with monoclonal antibody 1B4 (10 μg/mL) and has been subtracted.

Adhesion of LFA-1 to ICAM-2 and ICAM-3 was studied (Figure 5BC). LFA-1 with the Y131F revertant binds similarly to wild-type LFA-1, but the revertant G284R did not bind to ICAM-2 and ICAM-3.

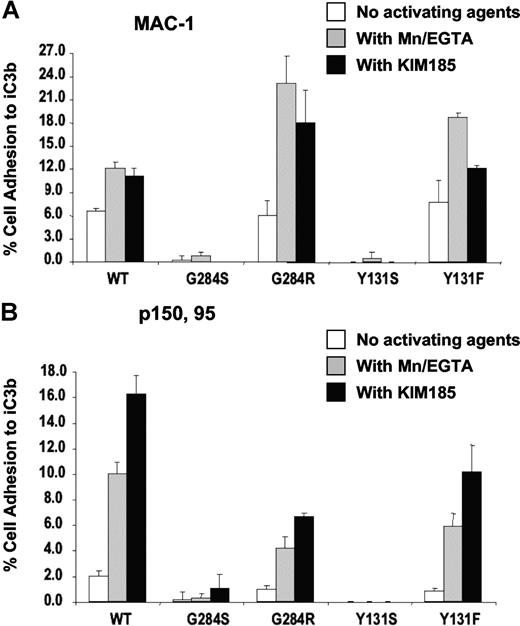

MAC-1 (CD11b/CD18) and p150,95 (CD11c/CD18) adhesion to iC3b upon activation with MnCl2 or KIM185 showed no binding when CD18 contained the Y131S or G284S mutations (Figure 6A,B). However, both revertants Y131F and G284R were activated to bind iC3b to levels similar to the wild type. Therefore, the initial mutant CD18 proteins of patients 1 and 2 are dysfunctional in terms of adhesion to specific ligands. The revertant form of CD18 protein from patient 1 (Y131F) can support coexpression of CD18 and all 3 alpha chains. The revertant form of CD18 from patient 2 (G284R), however, can support the expression and functions only for CD11b/CD18 and CD11c/CD18, but not for CD11a/CD18.

Adhesion of transfectants. Adhesion of Mac-1/(CD11b/CD18) (A) and p150,95/(CD11c/CD18) (B) transfectants to iC3b. Adhesion was done in the absence of activating agents, in the presence of 0.5 mM MnCl2, or with the activating monoclonal antibody KIM185 (2.5 μg/mL).

Adhesion of transfectants. Adhesion of Mac-1/(CD11b/CD18) (A) and p150,95/(CD11c/CD18) (B) transfectants to iC3b. Adhesion was done in the absence of activating agents, in the presence of 0.5 mM MnCl2, or with the activating monoclonal antibody KIM185 (2.5 μg/mL).

Discussion

We have identified 3 adult LAD-1 patients with somatic mosaicism who survived into adulthood without allogeneic bone marrow transplants. In all 3 patients the reversion mutations were heterozygous. None of the other known mechanisms of reversion in the cases described was evident.8,11 Allelic change was observed only in the genomic DNA from a small subset of circulating CD8+ T cells, but not in neutrophils, monocytes, CD4+ T cells, or B cells. Microsatellite analyses proved that the lymphocytes carrying both the mutant and revertant CD18 alleles were endogenous in each patient, ruling out the possibility of persistently engrafted maternal or allogeneic T cells. In 2 patients with different homozygous missense mutations, reversion was detected on only 1 of the 2 alleles. In these patients' CD18+ T cells, reversion was not to the wild type but to a third amino acid. A single case of somatic reversion of a LAD-1 mutation to WT was recently reported.35 In that compound heterozygous patient, reversion to WT was detected on one allele in a subset of T cells, presumably inducing normal binding and function, similar to previous reports of somatic reversion to WT, as seen in our patient 3. In contrast to that report and most reports in patients with immunodeficiency,1,2,4,5,9,10 our patients 1 and 2 had novel reversions that partially or fully restored the function but were not WT. Therefore, our patients illustrate clearly that it is the reversion to relatively normal function that is important in the expansion of these cells, and not the reversion to WT sequence.

Rare cases of somatic mosaicism resulting from reversion of inherited mutations have been reported that lead to attenuation of blood cell disorders.1,,,,–6,8 The impact of the revertant cells, particularly their representation in the peripheral blood pool, has been of interest, as it serves to predict the number of revertant cells needed to gauge the lower limits needed for successful gene correction or transplantation. Revertant mosaicism has been described in primary T-cell defects such as adenosine deaminase deficiency, X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency, and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome.1,2,4,5,9,10 Reversions in primary T-cell immunodeficiencies have been single case reports, without any series of patients identified.5,9,10,36,37 Spontaneous reversion of mutations or second-site mutations restoring function are more valuable if the corrected cells acquire a selective survival or growth advantage leading to improved expansion or persistence. A similar survival or growth advantage may have helped these long-lived memory effector T cells populate and persist in the peripheral blood in LAD-1.

Since the reverted amino acid sequences in our patients were not among the reported polymorphisms of CD18, functional analyses were critical. CD18 with the 131F revertant was functional, as determined by heterodimer formation with α integrin subunits (CD11a, b, and c) and their capacity to mediate adhesion to the ligands tested. In contrast, CD18 with the 284R revertant did not function fully with CD11a for heterodimer formation or adhesion to the ICAMs, but was able to support heterodimer formation with CD11b and CD11c and adhesion to iC3b. This residual defect in 284R emphasizes the discrete capacities of CD18 to interact with different CD11 subunits. It also indicates a complex structural interaction between the α and β subunits.

In patient 3, a compound heterozygote,27 the intronic point mutation responsible for the splicing defect reverted to wild type, while the point mutation in the coding sequence did not. In this same patient, revertants were seen only among cytotoxic T cells expressing CD3+/CD8+/CD57+ and lacking CD28. On the other hand, patients 1 and 2 had small percentages of revertant NK (CD3−/CD16/CD56+) cells (1% and 5% of CD18+ lymphocytes, respectively), in addition to the cytotoxic T cells. The CD18+ revertants also had intracellular perforin (data not shown), consistent with their cytotoxic potential. CD18+ T cells carried predominantly αβ TCR and were CD27−, which places them in the category of memory effector cells.38 Since the incidence of corrected cells was highest for memory T cells, it is likely that some degree of expansion occurred.

The limitation of reversion mutations to subsets of cytotoxic lymphocytes in LAD-1 suggests that the cytotoxic T cells have some predisposition to mutation through their propensity for DNA rearrangement and to positive selection, possibly through their anti-infective capacity. A selective advantage for these revertant cytotoxic T cells, presumably due to functional CD18 expression and therefore an advantage in proliferation, activation, or both, is possible. Inflammatory bowel disease in all 3 patients leaves open the possibility that these cells may be disadvantageous to the host. However, the ileal tissue from patient 3 did not show predominant CD18+ cells.21 Eosinophils, lymphocytes, and mononuclear cells can traffic to tissues with the help of the VLA-4/VCAM-1 receptor/ligand pair, whereas neutrophils cannot.

We were unable to identify reversions in progenitor cells, neutrophils, or monocytes, indicating that these events did not take place at a pluripotent stem cell level, but occurred in lineage-committed precursors. Even if the reversion occurred in a multipotent hematopoietic progenitor, it did not appear to confer proliferative advantage outside the T-cell lineage. Alternatively, these patients may have been born T-cell mosaics for CD18 expression, or they may have reverted early in life. Although it is theoretically possible that CD18+ myeloid cells could be formed and transit to the tissue without detection in the peripheral blood, we found no evidence of CD18+ staining in bowel biopsies, nor did we find any CD18+ stem cells in the circulation (data not shown). We are unable to determine the earliest time point these cells were detectable in peripheral blood since we do not have PBMCs dating as early as birth or infancy. However, the absence of these reverted alleles in their parents proves that these reversion mutations are endogenous to our patients.

The interaction and cross activation of TCR and CD18 is important, as is the role of CD18 in CD8+ T-cell homing, recirculation, and survival.39,40 These reversion mutations illustrate the need to look carefully at unusual patients and to perform both sequence and functional analyses in complex cases. Whether these reversion mutations have any effect on patient survival remains to be determined. The fact that these reversions have been identified in adult patients with LAD-1 leaves open the question whether these reversions are cause or consequence of long-term survival in this severe immunodeficiency.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr John Gallin for his guidance and expertise he shared with us regarding LAD-1. We also acknowledge Dr Douglas Kuhns and Debra Long Priel for their contribution in performing neutrophil function assays and Dr Thomas Bauer for his help and expertise. We are indebted to our patients and their families.

This study was supported by DHHS, NIH, and NIAID intramural funds.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: G.U. designed research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; E.T. performed research and contributed vital new reagents or analytical tools; S.D.R. analyzed data; A.P.H., J.M.S., G.F.L., and M.R.B. performed research; M.E.H., S.M.A., and M.R.K. contributed vital new reagents or analytical tools; J.B.O. and T.A.F. analyzed data; S.K.A.L. designed research, performed research, contributed vital new reagents or analytical tools, and analyzed data; S.M.H. cared for the patients, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Steven M. Holland, Bldg 10, CRC B3–4141, MSC 1684, Bethesda, MD 20892-1684; e-mail: smh@nih.gov; Gulbu Uzel, Bldg 10, CRC B3–4141, MSC 1684, Bethesda, MD 20892-1684; e-mail: guzel@mail.nih.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal