In CD34+ acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the malignant stem cells reside in the CD38− compartment. We have shown before that the frequency of such CD34+CD38− cells at diagnosis correlates with minimal residual disease (MRD) frequency after chemotherapy and with survival. Specific targeting of CD34+CD38− cells might thus offer therapeutic options. Previously, we found that C-type lectin-like molecule-1 (CLL-1) has high expression on the whole blast compartment in the majority of AML cases. We now show that CLL-1 expression is also present on the CD34+CD38− stem- cell compartment in AML (77/89 patients). The CD34+CLL-1+ population, containing the CD34+CD38−CLL-1+ cells, does engraft in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mice with outgrowth to CLL-1+ blasts. CLL-1 expression was not different between diagnosis and relapse (n = 9). In remission, both CLL-1− normal and CLL-1+ malignant CD34+CD38− cells were present. A high CLL-1+ fraction was associated with quick relapse. CLL-1 expression is completely absent both on CD34+CD38− cells in normal (n = 11) and in regenerating bone marrow controls (n = 6). This AML stem-cell specificity of the anti-CLL-1 antibody under all conditions of disease and the leukemia-initiating properties of CD34+CLL-1+ cells indicate that anti–CLL-1 antibody enables both AML-specific stem-cell detection and possibly antigen-targeting in future.

Introduction

Despite high-dose chemotherapy, only 30% to 40% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) survive, which is due mainly to relapse of the disease.1 AML is generally regarded as a stem-cell disease. However, there is debate whether normal stem cells undergoing leukemogenic mutations is the explanation for leukemogenesis. Alternatively, leukemogenic mutations occurring at a later developmental stage, resulting in stem cell–like behavior, might be an alternative or additional option.2,–4 For CD34+ AML, several authors have shown that leukemic stem cells are present in the CD34+CD38− compartment.5,6 It has been proven in vitro that these stem cells are more resistant to chemotherapy, compared with the progenitor CD34+CD38+ cells.7 In vivo, after chemotherapy, the residual malignant CD34+CD38− cells are thought to differentiate to a limited extent, producing leukemic cells with an immunophenotype, which usually reflects that at diagnosis. Sensitive techniques allow early detection of small numbers of these differentiated leukemic cells, called minimal residual disease (MRD), which eventually causes relapse of the disease.8 Since in this concept the stem cell is the origin of MRD and relapse, stem cell–targeted therapy would be of potentially high benefit for AML patients. Moreover, early detection of leukemic stem cells after chemotherapeutic treatment might offer prognostic value in predicting relapse of the disease. Different options for stem-cell identification and/or targeted therapy have been described such as anti-CD123, anti-CD44, and anti-CD33, but all have some (potential) disadvantages, including expression on normal stem cells and/or nonhematologic tissues.9,–11 Since the bone marrow of a (chemotherapy-) treated patient cannot be considered normal, it is extremely important to study whether after treatment normal stem cells in such regenerating bone marrow remain negative for the antigen of interest. So far, this has not been examined for CD33, CD44, and CD123

In this paper, we focus on the newly discovered antigen CLL-1, which we have described to be present on the majority of CD34+ as well as CD34− AML cases.12 In peripheral blood, both monocytes and granulocytes show some CLL-1 expression, while it is absent in other tissues.12 The intracellular domain of CLL-1 contains both an immunotyrosine-based inhibition motif as well as a YXXM motif, suggesting a role for CLL-1 as a signaling receptor. Phosphorylation of immunotyrosine-based inhibition motif–containing receptors on a variety of cells leads to inhibition of activation pathways via recruitment of the protein tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1, SHP-2, and SHIP.13 The YXXM motif, on the other hand, encompasses a potential SH2 domain–binding site for the p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase,14 an enzyme implicated in cellular activation pathways. Whether these properties can be translated to CLL-1 is still unknown.

We now demonstrate that CD34+CLL-1+ cells of AML patients showed engraftment in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice, indicating that CLL-1 is expressed on the leukemic stem-cell population in these patients. Also, we found CLL-1 to be present on AML and absent on normal CD34+CD38− cells at different time points of disease/treatment, which holds potential to serve as a tool to detect residual leukemic CD34+CD38− cells after therapy and as a possible target for therapy.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patient and control samples

The AML clinical protocols and the biologic studies were approved by the scientific research committee and the medical ethics committee of the VU University Medical Center (Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Leukemic cells of 89 patients presenting with CD34+ AML at our institute were obtained after informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, at diagnosis, and after chemotherapeutic treatment. CD34+ AML was defined as samples with a CD34 percentage more than 1 because we have previously shown that in samples with less than 1% CD34+ cells, these CD34+ cells are in general of normal origin.15 In 16 cases, bone marrow (BM) was not available at diagnosis and peripheral blood (PB) was used instead. After chemotherapeutic treatment, only BM was used. Relapse AML BM samples were obtained from 9 patients. Diagnosis of patients was based on morphology using French-American-British (FAB) classification, immunophenotyping, and cytogenetics.16 Control normal bone marrow (NBM) was obtained from 11 patients undergoing cardiac surgery after informed consent. Control regenerating bone marrow (RBM) was obtained from 3 patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, one patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, one patient with completely CD34− AML, and one patient with CLL-1− AML. Mobilized peripheral blood (MPB) was obtained from 6 non-AML patients after granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) stimulation.

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. AML samples were analyzed fresh (n = 52) or after storage in liquid nitrogen (n = 37). For expression studies after chemotherapy and in controls fresh material was used. For relapse studies (n = 9) in 4 cases frozen-thawed material was used. NOD/SCID mice repopulation experiments were performed using frozen-thawed material. Procedures used in this study have previously been validated for the use of both fresh and frozen-thawed material.17 In fresh samples, red blood cells were lysed using a 10-minute red blood cell lysis on ice with 10 mL lysis buffer (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, pH 7.4) and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% human serum albumin (HSA) added. Frozen samples were prepared using a Ficoll gradient (1.077 g/mL; Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany) and subsequent red blood cell lysis. Cells were then frozen in RPMI (Gibco, Paisley, United Kingdom) with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Greiner, Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands) and 10% DMSO (Riedel-de Haen, Seelze, Germany) in isopropanol-filled containers and subsequently stored in liquid nitrogen. When needed for analysis, cells were thawed and suspended in prewarmed RPMI with 40% FCS at 37°C. Cells were washed and enabled to recover for 45 minutes in RPMI with 40% FCS at 37°C. Cells were washed again and suspended in PBS with 0.1% HSA.17

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic . | Quantity . |

|---|---|

| Patients, no. | 89 |

| Male/female | 45/44 |

| Age at diagnosis, y, mean (range) | 55 (16-79) |

| WBC count at diagnosis,109/L, mean (range) | 38 (0.7-278) |

| FAB classification, no. (%) | |

| M0 | 5 (6) |

| M1 | 12 (13) |

| M2 | 14 (16) |

| M3 | 3 (3) |

| M4 | 11 (12) |

| M5 | 20 (23) |

| M6 | 3 (3) |

| Refractory anemia with excess blasts | 10 (11) |

| Refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation | 5 (6) |

| Not classified | 6 (7) |

| Cytogenetic risk group, no. (%) | |

| Favorable | 11 (12) |

| Intermediate | 49 (55) |

| Poor | 9 (10) |

| No metaphases | 20 (23) |

| Flt3 ITD, no. (%) | |

| Present | 22 (25) |

| Absent | 54 (61) |

| Not analyzed | 13 (14) |

| Characteristic . | Quantity . |

|---|---|

| Patients, no. | 89 |

| Male/female | 45/44 |

| Age at diagnosis, y, mean (range) | 55 (16-79) |

| WBC count at diagnosis,109/L, mean (range) | 38 (0.7-278) |

| FAB classification, no. (%) | |

| M0 | 5 (6) |

| M1 | 12 (13) |

| M2 | 14 (16) |

| M3 | 3 (3) |

| M4 | 11 (12) |

| M5 | 20 (23) |

| M6 | 3 (3) |

| Refractory anemia with excess blasts | 10 (11) |

| Refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation | 5 (6) |

| Not classified | 6 (7) |

| Cytogenetic risk group, no. (%) | |

| Favorable | 11 (12) |

| Intermediate | 49 (55) |

| Poor | 9 (10) |

| No metaphases | 20 (23) |

| Flt3 ITD, no. (%) | |

| Present | 22 (25) |

| Absent | 54 (61) |

| Not analyzed | 13 (14) |

WBC indicates white blood cell; FAB, French-American-British.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of CD34+CD38− cells

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) procedures have been described in detail before.17 In short, fresh cells were incubated with monoclonal antibodies for 15 minutes at room temperature, washed once in PBS containing 0.1% HSA, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Monoclonal antibody combinations contained fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–, phycoerythrin (PE)–, peridinyl chlorophyllin (PerCP)–, or allophycocyanin (APC)–labeled monoclonal antibodies. Anti-CD34 FITC, anti-CD34 PerCP, anti-CD45 PerCP, anti-CD45 APC, anti-CD38 APC, anti-CD123 PE, anti-CD7 PE, anti-CD19 PE, anti-CD33 FITC, anti-CD33 APC, and Via-Probe (7-amino-actinomycin D, 7AAD) were all from BD Biosciences (Basel, Switzerland); anti-CD34 FITC, which was used in some of the samples, was from Immunotech (Marseille, France); and annexinV FITC was from Nexins Research (Kattendijke, the Netherlands). Anti–CLL-1 and isotype controls (GBS and DNP) were from Crucell (Leiden, the Netherlands).

When frozen-thawed cells were used, annexinV FITC was included in the majority of samples to gate out apoptotic/dead cells before stem-cell assessment. In the remaining samples, this was done by Syto16 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) together with 7AAD in one tube, which enabled to gate out apoptotic/dead cells.18 The scatter properties of the viable cells were then used in the tube containing CLL-1.

PBS was used as a negative control, since for these specific antibodies isotype controls offered the same results.8 Data acquisition was performed using a FACScalibur (BD Biosciences) equipped with an argon and red diode laser, and analysis was performed using Cellquest software (BD Biosciences).

Blasts were identified by CD45dim/low side scatter characteristics according to Lacombe, taking into account that the CD34+CD38− population is a minor population.19

CD34+ cell selection

CD34+ cells were selected for the colony-forming unit (CFU) assays from NBM and for the fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of a sample from an AML patient in complete remission. After Ficoll separation and red blood cell lysis, mononuclear cells were incubated in PBS containing 5 mM EDTA and 0.1% HSA for 30 minutes at room temperature with CD34 Reagent (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), according to the manufacturer's procedure. Cells were washed and allowed to flow through a positive-selection column in a magnetic field (Automacs; Miltenyi Biotec). After 2 rounds of selection, CD34+ cells were collected. Purity was checked using flow cytometry and was more than 95% in all cases.

FACS sorting of CD34+ cells

FACS-sorted cells were used for CFU assays, FISH analysis, and NOD/SCID mice experiments. Cells were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature with Via-Probe (7AAD), anti-CD34 FITC, anti-CD38 APC, and anti–CLL-1 PE and washed in PBS containing 0.1% HSA. Cells were subsequently sorted using a FACS Vantage cell sorter with Turbo Sort upgrade (BD Biosciences) equipped with an argon (377G) and a helium-neon (127) laser, both from Spectra-Physics (Mountain View, CA) or a FACSAria equipped with solid-state lasers (red, blue, and violet; BD Biosciences). Cells were sorted based on viability (7AAD negative), CD34+ expression, CD38+ expression for the CFU assays, absence of CD38 for the FISH analysis, and CLL-1 expression. Purity of the sorted populations was more than 95%.

Transplantation of AML blasts in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency mice

Engraftment of CD34+CLL-1+ cells obtained at diagnosis was studied in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). The mice were irradiated with 3.5 Gy using a linear accelerator, delivering a 15-MV photon beam; tungsten jaws and multileafs collimated and shaped the irradiation field. The beam is calibrated, that is, the output for well-defined standard irradiation geometry is adjusted to a well-measured signal of the monitor chamber. The monitor chamber is the system in the accelerator controlling with high accuracy the dose delivery to the mice.

Cells used were from 3 patients; samples were selected for CD34 expression, CLL-1 expression on the CD34+CD38− cells, and engraftment in NOD/SCID mice. Patient 1 had AML with FAB M2 and Flt3 ITD; patient 2, with FAB M1 and Flt3 ITD; and patient 3, with FAB M6, Flt3 ITD, and +i(8)(q10)x2. CD34+CLL-1+ cells (3.5-8 × 106) were injected in the lateral tail vein. The mice were killed after 6 weeks in accordance with the institutional animal research regulations or at onset of clinical symptoms. BM was isolated from 2 femurs per mouse. Chimerism was determined using flow cytometric detection of human CD45 expression. Engrafted cells were analyzed for myeloid origin (CD33+ and CD19−), for malignant origin (presence of the leukemia-associated phenotype), and for CLL-1 expression.

FISH analysis

FISH analysis for t(8;21) was performed using LSI ETO/AML1 from Vysis (Downers Grove, IL) on FACS-sorted populations of a patient sample after chemotherapeutic treatment. Procedures have been described before.15

CFU assays

For CFU assays, cells obtained after CD34 isolation and FACS sorting, were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2, in a humidified incubator, in semisolid medium containing α-methylcellulose (Methocult GF H4434; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC). The number of colonies was evaluated after 14 days culture in semisolid medium.20 CFU–megakaryocyte (CFU-MK) assays were performed as described before.21

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using the SPSS 9.0 software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Mann-Whitney was used for CLL-1 expression in BM controls and AML samples. Wilcoxon signed-rank and Spearman correlation analysis were used for the analysis of the diagnosis-relapse samples. Spearman correlation analysis was also used for the correlation between the frequency of CD34+CD38−CLL-1+ cells and MRD frequency.

P values less than .05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

CLL-1 expression of CD34+CD38− cells in AML at diagnosis and in normal bone marrow

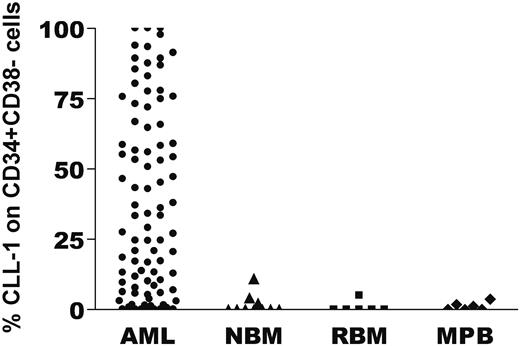

Previously we have shown that C-type lectin-like molecule-1 (CLL-1) is present on leukemic blasts at diagnosis in the majority of AML cases (68 of 74).12 Now CD34+ AML samples at diagnosis were analyzed for CLL-1 expression in the CD34+CD38− stem cell compartment. Representative examples of CLL-1 staining on CD34+CD38− cells are depicted in Figure 1. In 77 of 89 CD34+AML cases the CD34+CD38− cells showed a positive shift (compared with the isotype control) for CLL-1; because in part of the cases these shifts were small, overall (n = 89) a median CLL-1 expression of 33% was found for the CD34+CD38− compartment (Figure 2). CLL-1 expression in the CD34+CD38− compartment was found throughout all FAB subtypes studied. CLL-1 expression on the CD34+CD38− cells correlated neither with any AML subtype nor with prognosis in our patient cohort. Although in NBM samples the CD34+CD38+ progenitor population was partly CLL-1+,12 the CD34+CD38− cells were CLL-1− (Figures 1G,H, 2). To conclude, CLL-1 is specifically expressed on AML CD34+CD38− cells and not on NBM CD34+CD38− cells.

Examples of CLL-1 expression in AML samples at diagnosis and in normal bone marrow. After labeling of the cells with the appropriate antibody combinations, the CD45dimCD34+CD38− cells were identified by a precise gating strategy (as described in “Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of CD34+CD38− cells”; not shown) with subsequent detection of isotype and CLL-1 expression. For the CD34− AML (E-F) only blast gating (CD45dim) was performed. (A-F) Isotype and CLL-1 expression in AML samples. The percentages in the lower right quadrant indicate CLL-1 expression as a percentage of the CD34+CD38− compartment; in the lower left quadrant, the percentage CLL-1− cells within the CD34+CD38− compartment is shown. (B) An example of CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− cells close to the median. (D) An example of a high CLL-1 expression. (F) A representative example of CLL-1 expression in a CD34− AML sample. (H) The absence of CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− cells of normal bone marrow. Note that CLL-1 is expressed on part of the progenitor population.

Examples of CLL-1 expression in AML samples at diagnosis and in normal bone marrow. After labeling of the cells with the appropriate antibody combinations, the CD45dimCD34+CD38− cells were identified by a precise gating strategy (as described in “Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of CD34+CD38− cells”; not shown) with subsequent detection of isotype and CLL-1 expression. For the CD34− AML (E-F) only blast gating (CD45dim) was performed. (A-F) Isotype and CLL-1 expression in AML samples. The percentages in the lower right quadrant indicate CLL-1 expression as a percentage of the CD34+CD38− compartment; in the lower left quadrant, the percentage CLL-1− cells within the CD34+CD38− compartment is shown. (B) An example of CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− cells close to the median. (D) An example of a high CLL-1 expression. (F) A representative example of CLL-1 expression in a CD34− AML sample. (H) The absence of CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− cells of normal bone marrow. Note that CLL-1 is expressed on part of the progenitor population.

CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− stem cells in AML, normal bone marrow (NBM), regenerating bone marrow (RBM), and G-CSF–mobilized peripheral blood (MPB). After labeling of the cells with the appropriate antibody combinations, the CD34+CD38− cells were identified by a precise gating strategy (as described in “Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of CD34+CD38−”) and subsequently CLL-1 expression was determined. The percentage of CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− cells for every individual patient and control is depicted with a symbol. In NBM, median CLL-1 expression was 0% (range, 0%-11%; n = 10); in RBM, 0% (range, 0%-5%; n = 6); and in mobilized peripheral blood (MPB), 0.6% (range, 0%-3.7%; n = 6). The CD34+ FAB M3 samples of this study showed CLL-1 expression on the CD34+CD38− cells of 17%, 83%, and 89%.

CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− stem cells in AML, normal bone marrow (NBM), regenerating bone marrow (RBM), and G-CSF–mobilized peripheral blood (MPB). After labeling of the cells with the appropriate antibody combinations, the CD34+CD38− cells were identified by a precise gating strategy (as described in “Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of CD34+CD38−”) and subsequently CLL-1 expression was determined. The percentage of CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− cells for every individual patient and control is depicted with a symbol. In NBM, median CLL-1 expression was 0% (range, 0%-11%; n = 10); in RBM, 0% (range, 0%-5%; n = 6); and in mobilized peripheral blood (MPB), 0.6% (range, 0%-3.7%; n = 6). The CD34+ FAB M3 samples of this study showed CLL-1 expression on the CD34+CD38− cells of 17%, 83%, and 89%.

CLL-1–expressing CD34+ cells contain leukemia-initiating stem cells

NOD/SCID transplantation experiments were performed to show that the CD34+CLL-1+ compartment contains leukemic stem cells. Of the 89 AML patients, we had cells for NOD/SCID experiments from 10 patients. The total blast population from these patients was transplanted into NOD/SCID mice, which resulted in engraftment of human cells in 3 of 10 patients. From these 3 AML patients (with a CD34+CD38− compartment that was homogeneously positive for CLL-1) the CD34+CLL-1+ cell population was FACS sorted and injected into sublethally irradiated NOD/SCID mice. After 6 weeks, the mice were killed. The engrafted CD45+ cells were of myeloid origin (ie, CD33+ and CD19−), had a leukemia-associated immunophenotype, and showed CLL-1 expression on all blasts (Figure 3A-I). Engraftment of human cells was found for samples of all 3 patients and in all mice (Figure 4). Therefore, we can conclude that the CD34+CLL-1+ population of these 3 patients does contain CLL-1–expressing leukemic stem cells.

Flow cytometry of engrafted cells in NOD/SCID mice. FACS-sorted CD34+CLL-1+ cells from 3 different AML patients were transplanted into NOD/SCID mice. Six weeks after transplantation, the mice were killed and engraftment of human cells in these mice was studied using human anti-CD45 labeling. The engrafted cells were analyzed for myeloid origin (CD19− and CD33+, data not shown), leukemia-associated phenotype, and CLL-1 expression. Patient numbers are the same as in Figure 4. (A-E) The results of engrafted cells in 1 mouse of 3 that received a transplant of cells from patient 2 are shown. (A) CLL-1 expression on CD34+ cells at diagnosis (the CD34− cells in this sample were also CLL-1+, not shown). (B) Aberrant expression of CD7 on part of the leukemic CD34+ cells at diagnosis. (C) The CD45+ human population within the white blood cell compartment of the mouse. (D) The human cells that grew out of the transplanted CD34+CLL-1+ cells are all CLL-1+, similar to the whole blast compartment at diagnosis. (E) Similar to diagnosis, part of the cells again show aberrant CD7 expression. (F,H) The human CD45+ population within the white blood cell compartment of mice that received a transplant of cells from patients 3 and 1. CLL-1 expression on engrafted cells is shown in panels G and I.

Flow cytometry of engrafted cells in NOD/SCID mice. FACS-sorted CD34+CLL-1+ cells from 3 different AML patients were transplanted into NOD/SCID mice. Six weeks after transplantation, the mice were killed and engraftment of human cells in these mice was studied using human anti-CD45 labeling. The engrafted cells were analyzed for myeloid origin (CD19− and CD33+, data not shown), leukemia-associated phenotype, and CLL-1 expression. Patient numbers are the same as in Figure 4. (A-E) The results of engrafted cells in 1 mouse of 3 that received a transplant of cells from patient 2 are shown. (A) CLL-1 expression on CD34+ cells at diagnosis (the CD34− cells in this sample were also CLL-1+, not shown). (B) Aberrant expression of CD7 on part of the leukemic CD34+ cells at diagnosis. (C) The CD45+ human population within the white blood cell compartment of the mouse. (D) The human cells that grew out of the transplanted CD34+CLL-1+ cells are all CLL-1+, similar to the whole blast compartment at diagnosis. (E) Similar to diagnosis, part of the cells again show aberrant CD7 expression. (F,H) The human CD45+ population within the white blood cell compartment of mice that received a transplant of cells from patients 3 and 1. CLL-1 expression on engrafted cells is shown in panels G and I.

Engraftment of CD34+CLL-1+ AML blasts in NOD/SCID mice. FACS-sorted CD34+CLL-1+ cells from 3 different AML patients were transplanted into NOD/SCID mice. Six weeks after transplantation, the mice were killed and engraftment of human cells in these mice was studied using human anti-CD45. In this figure, the overall results are depicted on a logarithmic scale; every symbol represents the percentage engraftment of human CD45+ cells in one mouse. In a mouse that received a transplant of the whole CD34+ population from patient 2, which included the CD34+CD38−CLL+, but also a clear CD34+CD38−CLL-1− population (15% of the CD34+CD38− population), outgrowth of CD45dimCD33+CD19− AML cells was likewise accompanied by outgrowth of CD45dimCD33−CD19+ cells (18% of human cells), which are presumably normal (data not shown).22 Horizontal lines represent the mean percentage engraftment of leukemic cells.

Engraftment of CD34+CLL-1+ AML blasts in NOD/SCID mice. FACS-sorted CD34+CLL-1+ cells from 3 different AML patients were transplanted into NOD/SCID mice. Six weeks after transplantation, the mice were killed and engraftment of human cells in these mice was studied using human anti-CD45. In this figure, the overall results are depicted on a logarithmic scale; every symbol represents the percentage engraftment of human CD45+ cells in one mouse. In a mouse that received a transplant of the whole CD34+ population from patient 2, which included the CD34+CD38−CLL+, but also a clear CD34+CD38−CLL-1− population (15% of the CD34+CD38− population), outgrowth of CD45dimCD33+CD19− AML cells was likewise accompanied by outgrowth of CD45dimCD33−CD19+ cells (18% of human cells), which are presumably normal (data not shown).22 Horizontal lines represent the mean percentage engraftment of leukemic cells.

Expression of CLL-1 in regenerating bone marrow and mobilized peripheral blood

Both for possible future therapeutic use and for specific detection of malignant stem cells, it is of utmost importance that during and after treatment, the nonmalignant CD34+CD38− normal hematopoietic stem cells should remain CLL-1−. To establish that, remission bone marrow of both non-AML patients and CD34− or CLL-1− AML patients was investigated. No CLL-1 expression on the CD34+CD38− stem-cell compartment was observed (Figure 2). Furthermore, since G-CSF mobilization is part of the several current AML treatment protocols, CLL-1 expression was determined in G-CSF–mobilized blood. The CD34+CD38− population was almost completely CLL-1− in all samples (Figure 2).

To conclude, normal CD34+CD38− cells remain CLL-1− in BM recovering after chemotherapy and in PB after mobilization with growth factors.

Identity of CLL-1+ and CLL-1− normal bone marrow progenitors

Our previous finding that CLL-1 is expressed on part of the CD34+CD38+ progenitor population in NBM12 was confirmed in 11 additional samples (median expression, 40%; ranging from 26%-60%). Next, the nature of the CD34+CD38+CLL-1+ and CD34+CD38+CLL-1− subpopulations in normal BM was determined by FACS sorting and subsequent application of different colony assays. Results are depicted in Figure 5. Most CFU–granulocyte macrophages (CFU-GMs) grew out of the CD34+CD38+CLL-1+ population (Figure 5 second pair of rows). All monocytic colonies originated from the CLL-1+ fraction, whereas the granulocytic colonies originated only in part from the CLL-1+ fraction (data not shown). These observations are in accordance with granulocytes and monocytes being CLL-1+.12 In contrast, erythroid colonies (BFU-Es) and megakaryocytic colonies (CFU-MKs) originated from the CD34+CD38+CLL-1− compartment. Therefore, targeting CLL-1+ cells using anti–CLL-1–based therapy would most likely affect only granulocyte recovery.

Colony-forming capacity of CLL-1–defined CD34 subpopulations in normal bone marrow. CD34+CD38+CLL-1− and CD34+CD38+CLL-1+ subpopulations were purified from NBM cells. Cell input was 2500 cells/mL for BFU-Es/CFU-GMs. Cell input for CFU-MKs was 5000 cells/mL. The number of colonies was determined after 14 days of culture. ■ shows the output of the CD34+CD38+CLL-1+ population; ▒, the CD34+CD38+CLL-1− population. The error bars show the standard deviation. Two (CFU-MK) and 3 (burst-forming unit–erythroid [BFU-E]/CFU-GM) independent experiments were performed, each in duplicate.

Colony-forming capacity of CLL-1–defined CD34 subpopulations in normal bone marrow. CD34+CD38+CLL-1− and CD34+CD38+CLL-1+ subpopulations were purified from NBM cells. Cell input was 2500 cells/mL for BFU-Es/CFU-GMs. Cell input for CFU-MKs was 5000 cells/mL. The number of colonies was determined after 14 days of culture. ■ shows the output of the CD34+CD38+CLL-1+ population; ▒, the CD34+CD38+CLL-1− population. The error bars show the standard deviation. Two (CFU-MK) and 3 (burst-forming unit–erythroid [BFU-E]/CFU-GM) independent experiments were performed, each in duplicate.

CLL-1 expression of AML CD34+CD38− cells at diagnosis versus relapse

For reliable assessment during treatment/disease of the AML stem-cell compartment using CLL-1, its expression should be stable in the course of the disease. Paired diagnosis/relapse samples of 9 AML patients covering a large range of CLL-1 expression showed no significant differences (P = .9) and were significantly correlated (R = 0.7, P = .04); median expression at diagnosis was 34% (range, 8%-91%) versus 42% (range, 5%-92%) at relapse.

CLL-1 expression of CD34+CD38− cells in remission bone marrow

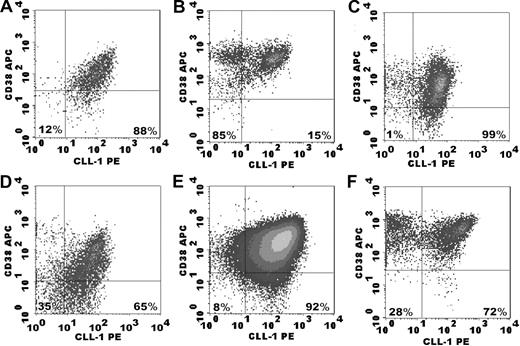

Subsequently, the possibility to discriminate CLL-1+ malignant CD34+CD38− cells from CLL-1− normal CD34+CD38− cells in remission bone marrow at different stages of treatment was investigated. Figure 6A,C,E shows representative flow cytometry pictures of 3 patients with high expression of CLL-1 on CD34+CD38− cells at diagnosis.

Examples of CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− cells in diagnosis and follow-up samples. Gating was performed based on CD45dim/SSC characteristics and CD34+ expression. Afterwards, CD38 and CLL-1 expression were determined. Similar to Figure 1, percentages shown concern the CLL-1+ and CLL-1− populations within the CD34+CD38− compartment. (A,B) An example of a patient who remained in continuous remission. This patient showed high CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− cells at diagnosis (A) but not after chemotherapy (B). Note the similarity with CLL-1 expression on normal bone marrow CD34+CD38− cells in Figure 1H. (C,D) A diagnosis and MRD picture, as in panels A and B, but now for a patient with a large proportion of CD34+CD38− cells being CLL-1+ in the MRD sample (D). CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− cells of an AML patient diagnosed with t(8,21), at diagnosis (E) and after first course of chemotherapy (F). In the remission sample, the malignant character of the CD34+CD38−CLL-1+ population could be confirmed using FISH technique.

Examples of CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− cells in diagnosis and follow-up samples. Gating was performed based on CD45dim/SSC characteristics and CD34+ expression. Afterwards, CD38 and CLL-1 expression were determined. Similar to Figure 1, percentages shown concern the CLL-1+ and CLL-1− populations within the CD34+CD38− compartment. (A,B) An example of a patient who remained in continuous remission. This patient showed high CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− cells at diagnosis (A) but not after chemotherapy (B). Note the similarity with CLL-1 expression on normal bone marrow CD34+CD38− cells in Figure 1H. (C,D) A diagnosis and MRD picture, as in panels A and B, but now for a patient with a large proportion of CD34+CD38− cells being CLL-1+ in the MRD sample (D). CLL-1 expression on CD34+CD38− cells of an AML patient diagnosed with t(8,21), at diagnosis (E) and after first course of chemotherapy (F). In the remission sample, the malignant character of the CD34+CD38−CLL-1+ population could be confirmed using FISH technique.

Patient one (Figure 6A,B) reached complete remission (CR) with resulting low frequency (0.01%) of minimal residual disease (MRD) as measured using leukemia-associated phenotype (LAP) expression, which is prognostically highly favorable.8 In line with this, CLL-1 expression was not present on the CD34+CD38− compartment (Figure 6B). Patient 2 (Figure 6C,D) reached CR, but with relatively high MRD frequency (0.89%). This patient quickly relapsed (within one month). CD34+CD38− cells remained largely CLL-1+ (Figure 6D), showing that the majority of BM stem cells were of malignant origin. Patient 3 (Figure 6E,F) reached CR after the first cycle of chemotherapy. The MRD frequency at that time point was 0.82%, which decreased to a prognostically favorable 0.02% after the second cycle of chemotherapy. Despite this, the patient relapsed within 6 months. In contrast to MRD, the fraction of CLL-1+ cells remained high; Figure 6F shows the first cycle with 72% CLL-1 expression on the CD34+CD38− cells. Since this patient was diagnosed with t(8;21), we were able to FACS sort the CD34+CD38− cells after the first cycle and to show by FISH analysis that, in very good agreement with Figure 6F, these were 80% positive for t(8;21). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for t(8;21) confirmed these results (data not shown). The malignant nature of the CD34+CD38−CLL-1+ population was further confirmed by aberrant expression of the natural killer (NK) cell marker CD56 (72%) on CD34+CD38− cells. The CD34+CD56+ immunophenotype has been shown to be a leukemia-associated phenotype and is used for MRD detection8,23,–25 and malignant stem-cell detection.26

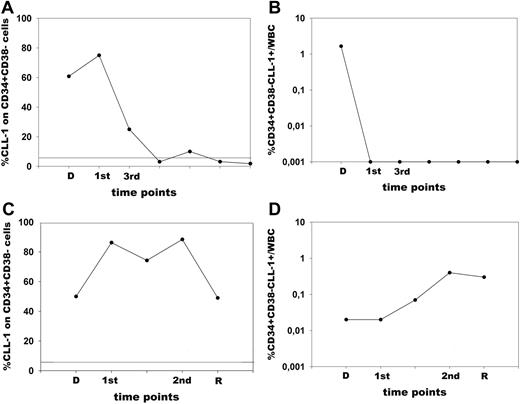

Figure 7 shows representative examples of follow-up analysis for 2 patients with a different course of the disease. Patient 1 reached CR, which has lasted now for 3 years. Figure 7A shows that this patient had high CLL-1 expression on the CD34+CD38− cells at diagnosis, but this expression decreased after chemo-therapy and remained absent; also the frequency of the CD34+CD38−CLL-1+ cells within the white blood cell (WBC) compartment (Figure 7B), which is a measure for the amount of CLL-1+CD34+CD38− cells, diminished and remained undetectable in time. Patient 2 reached CR, but relapsed after the second course of chemotherapy. CLL-1 was continuously expressed on the CD34+CD38− compartment, indicating that this compartment remained predominantly malignant at all time points analyzed (Figure 7C). Also the frequency of the CD34+CD38−CLL-1+ cells within the WBC compartment remained high and even increased toward relapse (Figure 7D). These figures are representations of similar patients who had a good remission (total n = 4) or a fast relapse (total n = 4).

Stem-cell parameters in AML patients with a different course of the disease. Cells were analyzed at diagnosis and at different time points during follow-up of 2 AML patients. (A,B) Patient 1. (C,D) Patient 2. (A,C) Malignant CD34+CD38− cells (defined by CLL-1) as a fraction of the total CD34+CD38− population. The solid line represents the background expression in RBM for CLL-1. (B,D) The frequency of CD34+CD38−CLL-1+ cells as percentage of the total WBC count. D indicates diagnosis; R, relapse; 1st, after first course of chemotherapy; and 2nd and 3rd, after the second and third course of chemotherapy, respectively. Patient 1 reached complete remission after the first course of chemotherapy and has been in continuous complete remission now for 3 years. Percentage of CLL-1 expression on the total CD34+CD38− compartment declined rapidly (A) as did the frequency of CD34+CD38−CLL-1+cells (B). Patient 2 reached complete remission after the first course of chemotherapy; however, a relapse occurred after the second course of chemotherapy. Although CR was reached, there was a continuous expression of CLL-1 on the CD34+CD38− cells (C). Also, the frequency of CD34+CD38−CLL-1+ cells did not decrease after chemotherapy, but even increased (D).

Stem-cell parameters in AML patients with a different course of the disease. Cells were analyzed at diagnosis and at different time points during follow-up of 2 AML patients. (A,B) Patient 1. (C,D) Patient 2. (A,C) Malignant CD34+CD38− cells (defined by CLL-1) as a fraction of the total CD34+CD38− population. The solid line represents the background expression in RBM for CLL-1. (B,D) The frequency of CD34+CD38−CLL-1+ cells as percentage of the total WBC count. D indicates diagnosis; R, relapse; 1st, after first course of chemotherapy; and 2nd and 3rd, after the second and third course of chemotherapy, respectively. Patient 1 reached complete remission after the first course of chemotherapy and has been in continuous complete remission now for 3 years. Percentage of CLL-1 expression on the total CD34+CD38− compartment declined rapidly (A) as did the frequency of CD34+CD38−CLL-1+cells (B). Patient 2 reached complete remission after the first course of chemotherapy; however, a relapse occurred after the second course of chemotherapy. Although CR was reached, there was a continuous expression of CLL-1 on the CD34+CD38− cells (C). Also, the frequency of CD34+CD38−CLL-1+ cells did not decrease after chemotherapy, but even increased (D).

These results indicate that, using CLL-1, malignant CD34+CD38− cells can indeed be detected in remission bone marrow and can be discriminated from the normal CD34+CD38− compartment. In a series of 13 patients, the putative possible role in prognosis was studied; in 8 of 9 cases with a quick relapse (ie, median 6 months after diagnosis; range, 3-11 months), CLL-1 expression on the whole stem-cell compartment was high (median, 62%; range, 27%-91%). This is in contrast to the patients still in remission (longest, 33 months), for which CLL-1+ stem cells were very low or absent in 4 of 5 cases (median, 0%; range, 0%-2%). Moreover we were able to show that, irrespective of the time point in disease/treatment, the frequency of CD34+CD38− cells within the WBC compartment significantly correlated with the frequency of MRD cells in these AML patients (n = 44 time points from 15 patients, R = 0.7, P < .001). MRD detection serves as the gold standard for risk assessment during treatment/disease, since it is a strong independent predictor for survival in AML patients as we and others have shown before.8,23,–25 The prognostic impact of MRD frequency in the present patient cohort has been published by us before.17

Discussion

In the present study, we show that CLL-1 is a marker of the malignant CD34+CD38− stem-cell compartment in the majority of CD34+ AML patients. Transplantation of the CD34+CLL-1+ cells, which putatively contain the CD34+CD38− stem cells capable of initiating leukemia, resulted in the development of leukemia in NOD/SCID mice in the 3 patients analyzed, with recovery of the diagnosis CLL-1 expression. CLL-1 expression turned out to be specific for leukemic CD34+CD38− cells, since it is absent both on normal CD34+CD38− resting bone marrow cells, on CD34+CD38− cells in treated patients with other diseases, and in CD34+CD38− cells obtained after G-CSF stimulation from non-AML patients. CLL-1 expression on the AML cells is likely stable, with no difference found between samples at diagnosis and relapse.

CLL-1 expression thus can be detected specifically on AML CD34+CD38− cells present after chemotherapy in AML patients in complete remission. In this way, CLL-1 expression may serve as marker for quantification of minimal residual stem-cell disease. The observation of quick relapses preceded by the presence of AML stem cells might offer clinically highly relevant information—in addition to the classic immunophenotypical MRD detection.8,23,–25 Moreover, these results show that CLL-1 is a potential target for antileukemia stem-cell therapy in remission bone marrow with AML stem cells still present. Since thrombocytopenia is a major side effect of most therapies in the majority of AML patients, and thus often a dose-limiting factor, it is of importance that CLL-1 is absent on megakaryocytic progenitors.

How would CLL-1 perform compared with CD123, CD33, and CD44? CD123 has been reported to be a stem cell–specific marker in AML.27 An advantage is the high staining intensity of CD34+CD38− cells observed in the majority of AML,27 which we were able to confirm (median expression, 98%; ranging from 5%-100% in 36 cases). The median expression on NBM CD34+CD38− cells (n = 5) was higher compared with CLL-1 (14.9%; ranging from 0%-18.8%), which was also found by others.11 To explore potential therapeutic use, a toxin-labeled IL-3 has been developed to target a functional IL3-receptor (consisting of both CD123 and CD131) and is currently being examined in (pre-) clinical studies.28 However, important control experiments, including possible staining of normal CD34+CD38− cells in regenerating bone marrow (RBM) of patients treated with chemotherapy, have not yet been reported. Since we have found high (median, 60%) CD123 expression on non–AML-regenerating bone marrow CD34+CD38− cells in 5 such cases (not shown), this issue needs serious attention. In sharp contrast, we did not detect CLL-1 on RBM CD34+CD38− cells.

CD33 is also expressed on CD34+CD38− stem cells of AML samples at diagnosis (median, 80%; range, 26%-100%; n = 13; A.v.R., unpublished data, October 2005). In contrast to anti-CD123 antibody and similar to anti–CLL-1 antibody, internalization of anti-CD33 occurs upon binding to the receptor.29 However, CD33 is not specific for AML stem cells; expression has been shown on normal stem cells.11 In our own experience too, CD33 is highly expressed on normal CD34+CD38− stem cells, both in resting NBM (median, 84%; range, 16%-100%; n = 9) and in RBM (61%, 79%, and 95% in 3 different BM samples). These observations might offer part of the explanation for the considerable hematologic toxicity in patients undergoing anti-CD33 therapy,30 part of which is certainly due to its effect on normal CD33+ progenitors,31,32 and, maybe even more importantly, on CD34+CD38− stem cells in normal bone marrow.11

CD44 has recently been described as a target on leukemic CD34+CD38− stem cells. It was shown that the activating antibody H90 results in differentiation of cells and in a major reduction of engraftment in NOD/SCID mice.9 However, CD44 is also weakly expressed on normal CD34+CD38− cells9 and on more differentiated hematopoietic cells. Regenerating bone marrow was not evaluated. Moreover, the different CD44 isoforms are expressed on many different tissues.10

An alternative approach to specifically target leukemic stem cells is inhibition of the proteasome. Normal CD34+ progenitor/stem cells do not express NF-κB, whereas CD34+CD38−CD123+ cells in AML do.33 The proteasome inhibitor MG-132, a well-known inhibitor of NF-κB, has been proposed for stem cell–targeted therapy.33 In vitro there is synergism between this NF-κB inhibitor and a conventional chemotherapeutic agent, idarubicin.34 Also, parthenolide, has been proposed to selectively target leukemic stem cells while sparing normal hematopoietic cells.35

Internalization has been described for CLL-1 after incubation with the antibody.12 However it is unlikely that the anti–CLL-1 antibody as such will have antileukemic effect, since Moab binding to the CLL-1+ HL60 cells had no effect on cell proliferation using a tritium-thymidine assay, while culturing normal CD34+ cells in a long-term culture system in the presence of anti–CLL-1 antibody has no effect on CFU-E and CFU-GM colony formation (data not shown). Also, CLL-1 labeling of cells did not influence engraftment of AML CD34+ cells in NOD/SCID mice (not shown). It is thus unlikely, although still unknown, that induction of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and complement-dependent cytotoxicity via CLL-1 will be an effective targeting mechanism. However, the putative function of CLL-1 in signal transduction13,14 might offer possibilities that can be translated in therapeutic applications. Another promising therapeutic strategy would be to couple a toxic moiety to the anti–CLL-1 antibody; if such a complex is internalized after antigen binding this would result in cell death after antigen-mediated uptake.

Anti–CLL-1 antibody–mediated therapy might be effective in CD34− AML as well, because CLL-1 expression is high in blast cells of CD34− AML (median, 96%; range, 15%-100%; n = 11; including 3 AML FAB M3). In the absence of a CD34+CD38− compartment, the side population (SP) defined by Hoechst staining is the most likely candidate36 to contain leukemic stem cells, which we indeed found in 6 of 9 CD34− AML patients. Preliminary results indicate that CLL-1 is indeed expressed on SP cells of 6 of 6 patients (median, 64%; range, 46%-100%). Also, other myeloid malignancies, such as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), show CLL-1 expression on the CD34+ cells.12

In conclusion, CLL-1 is a marker that is expressed on AML CD34+CD38− stem cells and not on normal CD34+CD38− cells under all conditions of treatment and disease. In 3 patients tested, we found that CD34+CLL-1+ cells repopulate in sublethally irradiated NOD/SCID mice, indicating that they contain leukemia-initiating cells. The use of anti–CLL-1 for the detection of minimal residual disease would offer an attractive approach, in addition to the established MRD frequency assessments, both as a prognostic marker and to guide time points for therapeutic intervention. Moreover, these unique properties might be exploited for the development of effective antibody conjugates for stem cell–directed therapy.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Floortje Kessler for assistance with the CFU-MK assay and Rob Dee (Sanquin Research, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) for performing qPCR of t(8;21). The Department of Cardiac Surgery and the patients are acknowledged for providing healthy bone marrow samples.

Authorship

Contribution: A.v.R. designed part of the research, performed the main part of the experiments and data analysis, and wrote the paper; G.A.M.S.D. designed part of the research; A.K. performed part of the experiments; E.J.R. designed part of the research and performed part of the experiments; N.F. guided and carried out part of the research and data analysis and reviewed the paper; B.M. performed part of the experiments; M.S.W. performed part of the experiments; S.Z. guided part of the research and reviewed the paper; G.J.O. was responsible for the availability of clinical samples and reviewed the paper; and G.J.S. designed and guided the main part of the study and was the main reviewer of the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gerrit Jan Schuurhuis, VU University Medical Center, Department of Hematology, CCA 4.28, De Boelelaan 1117, 1081 HV Amsterdam; e-mail:gj.schuurhuis@vumc.nl.

![Figure 5. Colony-forming capacity of CLL-1–defined CD34 subpopulations in normal bone marrow. CD34+CD38+CLL-1− and CD34+CD38+CLL-1+ subpopulations were purified from NBM cells. Cell input was 2500 cells/mL for BFU-Es/CFU-GMs. Cell input for CFU-MKs was 5000 cells/mL. The number of colonies was determined after 14 days of culture. ■ shows the output of the CD34+CD38+CLL-1+ population; ▒, the CD34+CD38+CLL-1− population. The error bars show the standard deviation. Two (CFU-MK) and 3 (burst-forming unit–erythroid [BFU-E]/CFU-GM) independent experiments were performed, each in duplicate.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/110/7/10.1182_blood-2007-03-083048/2/m_zh80200708200005.jpeg?Expires=1769086813&Signature=cE0L7SaCqypDDWowJE8he15m8po6FKCPtzhrKXCvZ6tXpycU2M0zAzf8cvAM4uJQXd-opyxd1oiIM4YJYbskQFxp3xehRe1PptForRk-HH~VPGVaYAI-Kif6xVBNwLVwfof4nt2ePMQ7~ExDWRaJOGHeZ0D07JkXS-FdPl2BgdYTOYmTl-8EQo175X819RYkuZE~O~WRFWR~G98VW2sdwOFmJN5hKD2B5~R-1JN2VnnMkDehq92f2uGp3ml2aWsRnIBiyfigH58xEBvX~tQ4jj65nkO35ETRzvD-paLzq7ZEan28zwSMQnyzvNoZ9JaYXwVVkIaKKD4TtnFrumwQuw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal