The BRCA1 associated C-terminal helicase (BACH1, designated FANCJ) is implicated in the chromosomal instability genetic disorder Fanconi anemia (FA) and hereditary breast cancer. A critical role of FANCJ helicase may be to restart replication as a component of downstream events that occur during the repair of DNA cross-links or double-strand breaks. We investigated the potential interaction of FANCJ with replication protein A (RPA), a single-stranded DNA-binding protein implicated in both DNA replication and repair. FANCJ and RPA were shown to coimmunoprecipitate most likely through a direct interaction of FANCJ and the RPA70 subunit. Moreover, dependent on the presence of BRCA1, FANCJ colocalizes with RPA in nuclear foci after DNA damage. Our data are consistent with a model in which FANCJ associates with RPA in a DNA damage-inducible manner and through the protein interaction RPA stimulates FANCJ helicase to better unwind duplex DNA substrates. These findings identify RPA as the first regulatory partner of FANCJ. The FANCJ-RPA interaction is likely to be important for the role of the helicase to more efficiently unwind DNA repair intermediates to maintain genomic stability.

Introduction

Fanconi anemia (FA) is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by multiple congenital anomalies, progressive bone marrow failure, and high cancer risk.1 Cells from patients with FA exhibit spontaneous chromosomal instability and hypersensitivity to DNA interstrand cross-linking (ICL) agents. Although the precise mechanistic details of the FA/BRCA pathway of ICL repair are not well understood, progress has been made in the identification of the FA proteins that are required for the pathway.2 Among the 13 FA complementation groups from which all the FA genes have been cloned,3 only a few of the FA proteins are predicted to have direct roles in DNA metabolism. One of the recently identified FA proteins, shown to be responsible for complementation of the FA complementation group J,4,–6 is the BRCA1 associated C-terminal helicase (BACH1, designated FANCJ), originally identified as a protein associated with breast cancer. Two females among a cohort of 65 women with early-onset breast cancer were identified carrying 2 independent germ line sequence changes (P47A or M299I) in the FANCJ coding region and normal genotypes for BRCA1 and BRCA2.7 Truncating FANCJ mutations that cause FA in biallelic carriers confer susceptibility to breast cancer in monoallelic carriers.8 Clinically relevant mutations exist in the conserved iron-sulfur cluster of the FANCJ helicase domain.5,9,10 Interaction of FANCJ with BRCA1 and the existence of FANCJ mutations in patients with early-onset breast cancer and patients with FA have clarified that FANCJ exerts a tumor suppressor function

FANCJ has been proposed to function downstream of FANCD2 monoubiquitination, a critical event in the FA pathway.11 Evidence supports a role of FANCJ in a homologous recombination (HR) pathway of double-strand break (DSB) repair.6 DSB repair by HR is important in the late steps of processing ICLs. FA-J cells are hypersensitive to ICL agents,6,12 exhibit diminished BRCA1 foci in untreated cells, and have delayed ionizing radiation (IR)–induced BRCA1 foci.13 FANCJ helicase catalytically unwinds duplex DNA with a 5′ to 3′ directionality, preferentially binds and unwinds forked duplexes, and can unwind the invading strand of a 3-stranded D-loop structure, a key early intermediate of HR repair.9,14

A viable approach to understanding the role of FANCJ is to identify and characterize its interactions with other proteins implicated in HR repair. The BRCA1-FANCJ interaction depends on 2 intact BRCA BRCT repeats and FANCJ phosphorylation15,–17 and is required for DNA damage-induced checkpoint control.18 BRCA1 function at sites of DNA damage involves the assembly of a BRCA1 super complex containing BARD1, FANCJ, BRCA2, and Rad51 that is critical for the S phase checkpoint by inhibiting DNA synthesis at late-firing sites of replication initiation.19 FANCJ probably plays a critical role in HR-mediated DSB repair through its interaction with BRCA1.20

To better understand the roles of FANCJ in pathways of DNA repair, we have investigated its potential interaction with replication protein A (RPA), a single-stranded DNA-binding protein implicated in DNA replication and repair. Our findings show that FANCJ and RPA coimmunoprecipitate with each other and colocalize in nuclear foci after DNA damage or replicational stress. FANCJ and RPA directly bind to each other with high affinity by the RPA70 subunit. Although FANCJ is severely limited in unwinding even a 47 base pair (bp) forked duplex, the presence of RPA enables FANCJ to act as a much more processive helicase. The functional interaction between FANCJ and RPA is specific because the Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA binding (ESSB) protein failed to stimulate FANCJ helicase activity. The FANCJ-RPA complex is probably important for the role of the helicase in genome stability maintenance through its DNA repair function.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Immortalized fibroblasts FA-A (PD220), FA-J (EUFA030), and HeLa were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine at 37°C in 5% CO2. Immortalized FA-D2 (PD20) fibroblasts were grown in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 15% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% l -glutamine at 37°C in 5% CO2. HCC 1937 and BRCA1-reconstituted cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. For BRCA1 knockdown, smartpool BRCA1 siRNA (100 nM; Dharmacon, Chicago, IL) was transfected into HeLa cells using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen), and cells were used 48 hours after transfection. For FANCJ transfections, 3 μg plasmid encoding Myc-tagged FANCJ-WT, FANCJ-M299I, or FANCJ-P47A proteins7 were transfected into FA-J cells with Fugene 6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), and cells were used 36 hours after transfection.

Coimmunoprecipitation experiments

HeLa nuclear extracts (NEs) were prepared from exponentially growing cells as described previously.21 NE (1 mg protein) was incubated with rabbit anti-FANCJ polyclonal antibody (1 μg; Sigma, St Louis, MO), mouse anti-RPA70 monoclonal antibody (1 μg; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), or normal rabbit IgG antibody (1 μg; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) in buffer D (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 100 mM KCl, 10% glycerol) for 2 hours, tumbled with 20 μL protein-G agarose (Roche) for 2 hours at 4°C. Beads were washed with buffer D containing 0.1% Tween-20. Proteins were eluted by boiling in SDS sample buffer, resolved on 10% polyacrylamide Tris-glycine SDS gels, and transferred to PVDF membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Immunoprecipitations from FA mutant and BRCA1-depleted cells were performed using whole-cell lysates prepared as previously described.22 Membranes were probed for FANCJ, RPA, or BRCA1 using rabbit polyclonal anti-FANCJ (1:5000; Sigma), mouse anti-RPA70 monoclonal (1:100; Calbiochem), or mouse monoclonal anti-BRCA1 (Ab-4, 1:50; Oncogene, Seattle, WA) antibodies, respectively. Proteins on immunoblot were detected using ECL Plus (Amersham Biosciences).

Immunofluorescence cellular localization studies

Cells were grown as monolayer on chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY) as described. Mitomycin-C (MMC; 500 ng/mL; Sigma) or hydroxyurea (2 mM; Sigma) was added to the 50% to 80% confluent cultures for 16 hours before harvesting. For IR treatment, cells were irradiated at 10 Gy using Gammacell 40, a 137Cs source emitting at a fixed dose rate of 0.82 Gy/minute (Nordion International, Ottawa, ON) and subsequently incubated at 37°C for 6 hours before harvesting. Cells were fixed with formaldehyde (3.7% Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA) for 15 minutes, washed with PBS, and treated with 0.5% Triton (Sigma) at room temperature for 3 minutes followed by washing with PBS and blocking with 10% goat serum (Sigma) overnight at 4°C. Indirect immunostaining was performed by incubating cells in primary antibodies, rabbit anti-FANCJ polyclonal (1:250; Sigma), and mouse anti-RPA34 Ab-2 monoclonal (1:100; Calbiochem) for 1 hour at 37°C. After washes in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti–mouse IgG (1:400; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) and Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti–rabbit IgG (1:400, Invitrogen) secondary antibodies for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were washed 4 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, mounted with Prolong Gold containing DAPI (Invitrogen), and cured at room temperature in the dark for 24 hours. Immunofluorescence was performed on a Zeiss LSM 510 META inverted Axiovert 200M laser scan microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 oil DIC objective. Images were captured with a CCD camera and analyzed using LSM Browser software (Carl Zeiss). Physical and functional protein interaction assays are described in Document S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article.

Results

In vivo interaction of FANCJ and RPA

To explore whether endogenous FANCJ and RPA reside in a complex in vivo, coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed. Anti-FANCJ antibody precipitated both FANCJ and RPA from HeLa NE (Figure 1A lane 3). Twenty-two percent of the RPA from HeLa NE input (Figure 1A lane 1) was coimmunoprecipitated with FANCJ. Neither FANCJ nor RPA was precipitated when normal rabbit IgG was used (Figure 1A lane 2). Specificity of the FANCJ antibody was shown by using FA-J extracts. RPA failed to be precipitated by the FANCJ antibody (Figure 1A lane 5) despite its presence in FA-J extracts (Figure 1A lane 4). RPA was coimmunoprecipitated with FANCJ from the FA-J–corrected cells by the anti-FANCJ antibody (Figure 1A lane 9), whereas no RPA was precipitated in the control IgG sample (Figure 1A lane 10). The specificity of the FANCJ antibody was verified by the immunoprecipitation of BRCA1 as a positive control from the HeLa extract (Figure 1B). FANCJ and RPA coimmunoprecipitated in the presence of DNaseI or EtBr, albeit slightly reduced with EtBr (Figure 1C), suggesting that DNA is not essential for the interaction.

FANCJ and RPA are associated with each other in vivo and directly interact. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of RPA with FANCJ. FANCJ antibody coprecipitates FANCJ and RPA from HeLa or FA-J–corrected cells but not from the FA-J extracts. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-RPA (bottom) antibodies. (Lane 1) HeLa nuclear extract (15% of input), (lane 2) control immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extract using normal rabbit IgG, (lane 3) immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extract using rabbit anti-FANCJ antibody, (lane 4) FA-J whole-cell extract (WCE; 15% of input), (lane 5) immunoprecipitate from FA-J WCE using rabbit anti-FANCJ antibody, (lane 6) control precipitate from FA-J WCE using normal rabbit IgG, (lane 7) WCE from HeLa included as control for Western detection of FANCJ and RPA, (lane 8) FA-J corrected WCE (15% of input), (lane 9), immunoprecipitate from FA-J–corrected WCE using rabbit anti-FANCJ antibody, and (lane 10) control immunoprecipitate from FA-J–corrected WCE using normal rabbit IgG. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of BRCA1 with FANCJ. FANCJ antibody coprecipitates FANCJ and BRCA1 from HeLa nuclear extract. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-BRCA1 (bottom) antibodies. (Lane 1) HeLa nuclear extract (15% of input), (lane 2) immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extract using rabbit anti-FANCJ antibody, and (lane 3) control immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extract using normal rabbit IgG. (C) FANCJ antibody coprecipitates FANCJ and RPA from HeLa nuclear extracts in the presence of ethidium bromide or DNaseI. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-RPA (bottom) antibodies. (Lane 1) HeLa nuclear extract (15% of input), (lane 2) immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extract using rabbit anti-FANCJ antibody, (lanes 3 and 4) immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extracts in the presence of 2 μg/mL DNaseI or 10 μg/mL ethidium bromide using rabbit anti-FANCJ antibody, and (lane 5) control immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extract using normal rabbit IgG. (D,E) FANCJ and RPA form a complex by direct physical interaction. (D) RPA (96 nM heterotrimer, □) or ESSB (96 nM homotetramer, ■) was coated onto the ELISA plate. After blocking with 3% BSA, the wells were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified recombinant FANCJ protein (0-150 nM) for 60 minutes at 37°C. Wells were aspirated and washed 3 times, and bound FANCJ-WT protein was detected by ELISA with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against FANCJ. (E) Same as described for panel D except 2 μg/mL DNase I or 10 μg/mL ethidium bromide (EtBr) were incubated with RPA (96 nM) and FANCJ (77 nM) during the binding step in the corresponding wells. The values represent the mean of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate with standard deviation (SD) indicated by error bars. (F) FANCJ and RPA interact by the 70-kDa subunit of RPA. Purified RPA, ESSB, and BSA (as indicated above the lanes) were subjected to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 3 identical gels. The proteins bound to membranes were stained with Ponceau S or transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and incubated with either purified FANCJ (+FANCJ) or no protein (−FANCJ). Western blotting with anti-FANCJ antibody was then used to detect the presence of FANCJ on each membrane. The positions of the 70-, 32-, and 14-kDa subunits of RPA are indicated by asterisks. The positions of the molecular mass standards running parallel are shown on the left.

FANCJ and RPA are associated with each other in vivo and directly interact. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of RPA with FANCJ. FANCJ antibody coprecipitates FANCJ and RPA from HeLa or FA-J–corrected cells but not from the FA-J extracts. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-RPA (bottom) antibodies. (Lane 1) HeLa nuclear extract (15% of input), (lane 2) control immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extract using normal rabbit IgG, (lane 3) immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extract using rabbit anti-FANCJ antibody, (lane 4) FA-J whole-cell extract (WCE; 15% of input), (lane 5) immunoprecipitate from FA-J WCE using rabbit anti-FANCJ antibody, (lane 6) control precipitate from FA-J WCE using normal rabbit IgG, (lane 7) WCE from HeLa included as control for Western detection of FANCJ and RPA, (lane 8) FA-J corrected WCE (15% of input), (lane 9), immunoprecipitate from FA-J–corrected WCE using rabbit anti-FANCJ antibody, and (lane 10) control immunoprecipitate from FA-J–corrected WCE using normal rabbit IgG. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of BRCA1 with FANCJ. FANCJ antibody coprecipitates FANCJ and BRCA1 from HeLa nuclear extract. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-BRCA1 (bottom) antibodies. (Lane 1) HeLa nuclear extract (15% of input), (lane 2) immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extract using rabbit anti-FANCJ antibody, and (lane 3) control immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extract using normal rabbit IgG. (C) FANCJ antibody coprecipitates FANCJ and RPA from HeLa nuclear extracts in the presence of ethidium bromide or DNaseI. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-RPA (bottom) antibodies. (Lane 1) HeLa nuclear extract (15% of input), (lane 2) immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extract using rabbit anti-FANCJ antibody, (lanes 3 and 4) immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extracts in the presence of 2 μg/mL DNaseI or 10 μg/mL ethidium bromide using rabbit anti-FANCJ antibody, and (lane 5) control immunoprecipitate from HeLa nuclear extract using normal rabbit IgG. (D,E) FANCJ and RPA form a complex by direct physical interaction. (D) RPA (96 nM heterotrimer, □) or ESSB (96 nM homotetramer, ■) was coated onto the ELISA plate. After blocking with 3% BSA, the wells were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified recombinant FANCJ protein (0-150 nM) for 60 minutes at 37°C. Wells were aspirated and washed 3 times, and bound FANCJ-WT protein was detected by ELISA with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against FANCJ. (E) Same as described for panel D except 2 μg/mL DNase I or 10 μg/mL ethidium bromide (EtBr) were incubated with RPA (96 nM) and FANCJ (77 nM) during the binding step in the corresponding wells. The values represent the mean of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate with standard deviation (SD) indicated by error bars. (F) FANCJ and RPA interact by the 70-kDa subunit of RPA. Purified RPA, ESSB, and BSA (as indicated above the lanes) were subjected to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 3 identical gels. The proteins bound to membranes were stained with Ponceau S or transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and incubated with either purified FANCJ (+FANCJ) or no protein (−FANCJ). Western blotting with anti-FANCJ antibody was then used to detect the presence of FANCJ on each membrane. The positions of the 70-, 32-, and 14-kDa subunits of RPA are indicated by asterisks. The positions of the molecular mass standards running parallel are shown on the left.

FANCJ forms a direct complex with RPA

Enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assays (ELISAs) were used to test for a direct protein-protein interaction. Increasing concentrations of FANCJ were incubated in the presence of 3% BSA with RPA immobilized on microtiter wells, and the bound FANCJ protein was detected immunologically. Colorimetric signal was both dose dependent and saturable (Figure 1D). Specificity of this interaction was shown by the absence of color in wells precoated with ESSB (Figure 1D) or BSA (data not shown). The colorimetric signal from the FANCJ-RPA interaction was resistant to pretreatment of both FANCJ protein and RPA with DNase I (2 μg/mL) or EtBr (10 μg/mL) (Figure 1E), suggesting that a contaminating DNA bridge is not responsible for the signal. Specific binding of FANCJ to RPA was analyzed according to Scatchard binding theory. Data were analyzed by a Hill plot and found to be linear, indicating a single set of binding sites for RPA with FANCJ. The apparent dissociation constant (Kd) was determined to be 9.4 nM.

FANCJ directly binds to RPA70

To identify the subunit(s) of RPA that mediates the interaction with FANCJ, Far Western analysis was performed. RPA was immobilized on a nitrocellulose filter and incubated with purified FANCJ protein. The filter was washed to remove unbound protein, and FANCJ was detected by conventional Western blotting. As controls, the membrane also contained BSA and ESSB. The anti-FANCJ antibody detected a band at the position of the 70-kDa subunit RPA, whereas no band was seen at the positions of either BSA- or ESSB-negative controls or the 32- and 14-kDa RPA subunits (Figure 1F). Immunoreactivity at the position of the 70-kDa RPA subunit was not due to cross-reactivity of the anti-FANCJ antiserum with RPA, becausethis band was absent from the control blot that had been incubated with buffer alone (Figure 1F). We conclude that FANCJ binds to the RPA70 subunit.

FANCJ associates with RPA in a DNA damage-inducible manner

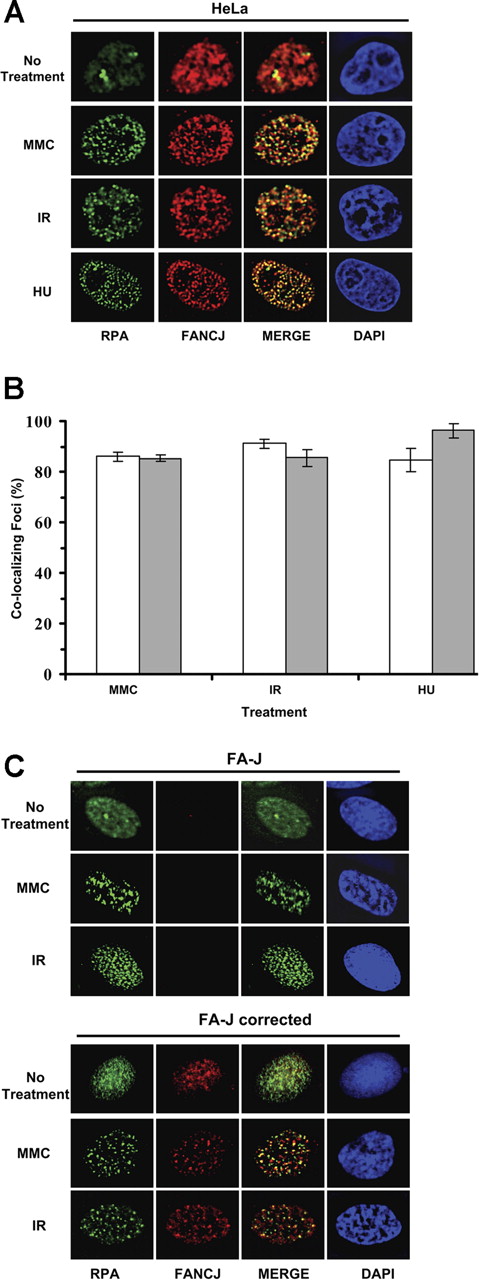

FANCJ and RPA strongly colocalized after DNA damage induced by IR or MMC or replicational stress induced by hydroxyurea (Figure 2A). Approximately 80% of FANCJ and RPA foci colocalized with each other after treatment with IR, MMC, or hydroxyurea (Figure 2B). Specificity of FANCJ antibody was shown by the absence of FANCJ staining in FA-J cells (Figure 2C). RPA foci were observed in FA-J cells after IR or MMC treatment, suggesting that the ability to form RPA foci after DNA damage was intact in the FA-J cells. FANCJ and RPA colocalized after MMC or IR treatment in the corrected FA-J cells (Figure 2C).

DNA damage-inducible colocalization of FANCJ helicase and RPA. (A) HeLa cells were treated with the DNA-damaging agents MMC (500 ng/mL) or hydroxyurea (2 mM) or exposed to 10 Gy IR as described in “Immunofluorescence cellular localization studies” After fixation and permeabilization, cells were incubated with anti-RPA (green) and anti-FANCJ (red) antibodies. After treatment with MMC, hydroxyurea, or IR, RPA localizes in nuclear foci that coincide with FANCJ foci as shown in the overlapped images. The yellow color results from the overlapping of the red and green foci in the merged images. In control untreated cells, RPA and FANCJ staining is diffuse. (B) Quantitation of FANCJ-RPA colocalizing foci as described in panel A. Percentages of RPA foci colocalizing with FANCJ are represented □, and percentages of FANCJ foci colocalizing with RPA are represented (▩). Experimental data are the mean of at least 3 independent experiments with standard deviations indicated by error bars. (C) FA-J vector and FA-J corrected cells were treated with the indicated DNA-damaging agents and processed for immunofluorescence as described above.

DNA damage-inducible colocalization of FANCJ helicase and RPA. (A) HeLa cells were treated with the DNA-damaging agents MMC (500 ng/mL) or hydroxyurea (2 mM) or exposed to 10 Gy IR as described in “Immunofluorescence cellular localization studies” After fixation and permeabilization, cells were incubated with anti-RPA (green) and anti-FANCJ (red) antibodies. After treatment with MMC, hydroxyurea, or IR, RPA localizes in nuclear foci that coincide with FANCJ foci as shown in the overlapped images. The yellow color results from the overlapping of the red and green foci in the merged images. In control untreated cells, RPA and FANCJ staining is diffuse. (B) Quantitation of FANCJ-RPA colocalizing foci as described in panel A. Percentages of RPA foci colocalizing with FANCJ are represented □, and percentages of FANCJ foci colocalizing with RPA are represented (▩). Experimental data are the mean of at least 3 independent experiments with standard deviations indicated by error bars. (C) FA-J vector and FA-J corrected cells were treated with the indicated DNA-damaging agents and processed for immunofluorescence as described above.

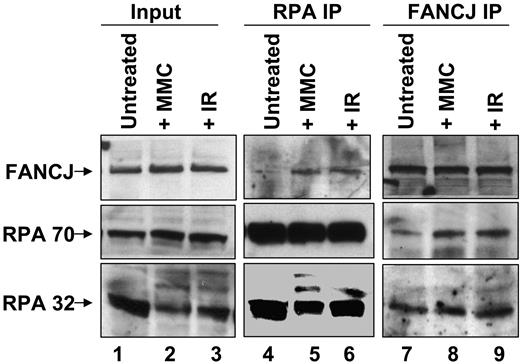

To determine the effect of DNA damage on FANCJ-RPA interaction, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments. The results show that RPA and FANCJ can be reciprocally immunoprecipitated (Figure 3). There was an increased signal for FANCJ in the RPA immunoprecipitates from cells exposed to IR or MMC compared with untreated cells (lanes 5 and 6 versus lane 4). Similarly, there was an increased signal for RPA in the FANCJ immunoprecipitates from damage-treated cells compared with untreated cells (lanes 8 and 9 versus lane 7). These results indicate a DNA damage-inducible association of the two proteins, consistent with their colocalization.

Coimmunoprecipitation of FANCJ and RPA after DNA damage. Nuclear extracts were prepared from HeLa cells that were untreated or exposed to IR (10 Gy) or MMC (500 ng/mL) and immunoprecipitated with anti-FANCJ or anti-RPA antibody as indicated. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-RPA70 or anti-RPA32 (bottom) antibodies.

Coimmunoprecipitation of FANCJ and RPA after DNA damage. Nuclear extracts were prepared from HeLa cells that were untreated or exposed to IR (10 Gy) or MMC (500 ng/mL) and immunoprecipitated with anti-FANCJ or anti-RPA antibody as indicated. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-RPA70 or anti-RPA32 (bottom) antibodies.

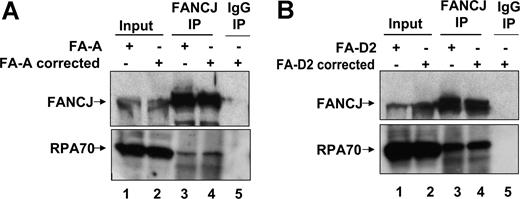

FANCJ-RPA interaction is intact in FA mutant cells

We next asked whether FANCJ-RPA interaction was defective in FA-deficient cells. Because FANCJ is implicated in a downstream event of FANCD2 monoubiquitination, we investigated the possibility that a mutation in an upstream member (core complex protein FANCA) of the FA pathway might affect the interaction of FANCJ and RPA. FANCJ and RPA were coimmunoprecipitated from whole-cell lysate of the FA-A mutant cell line (Figure 4A), suggesting the ability of FANCJ and RPA to be associated with each other is intact in cells that are defective in an event upstream of FANCD2 monoubiquitination. We also examined FA-D2 mutant cells and their corrected counterpart for FANCJ-RPA interaction and show that the two proteins could be coimmunoprecipitated from the whole-cell lysates (Figure 4B).

FANCJ-RPA interaction is intact in FA mutant cells coimmunoprecipitation of FANCJ and RPA in FA-A and FA-D2 cells. Coimmunoprecipitation of RPA with FANCJ in FA-A vector and FA-A corrected cells (A) or FA-D2 vector and FA-D2–corrected cells (B) with the use of FANCJ antibody. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-RPA (bottom) antibodies. Input represents 15% of WCE input for coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Control immunoprecipitate from WCE of FA-A–corrected or FA-D2–corrected cells with the use of normal rabbit IgG is shown in lane 5.

FANCJ-RPA interaction is intact in FA mutant cells coimmunoprecipitation of FANCJ and RPA in FA-A and FA-D2 cells. Coimmunoprecipitation of RPA with FANCJ in FA-A vector and FA-A corrected cells (A) or FA-D2 vector and FA-D2–corrected cells (B) with the use of FANCJ antibody. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-RPA (bottom) antibodies. Input represents 15% of WCE input for coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Control immunoprecipitate from WCE of FA-A–corrected or FA-D2–corrected cells with the use of normal rabbit IgG is shown in lane 5.

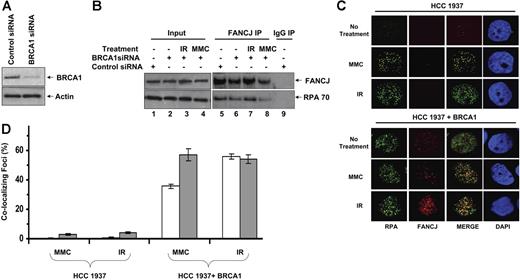

FANCJ-RPA interaction in BRCA1-deficient cells

We next asked whether a deficiency in the FANCJ-interacting partner BRCA1 might affect the interaction of FANCJ and RPA. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed by using control or BRCA1 siRNA-depleted HeLa cells (Figure 5A). FANCJ and RPA were coimmunoprecipitated with each other in the absence or presence of exogenous DNA damage (IR, MMC) under conditions when BRCA1 is depleted (Figure 5B).

Effect of BRCA1 deficiency on the DNA damage-inducible association of FANCJ and RPA in BRCA1-deficient cells. (A) siRNA depletion of BRCA1. WCE of HeLa cells transfected with control or BRCA1 siRNA were probed using an antibody against BRCA1. Actin serves as a loading control. (B) WCEs were prepared from control siRNA or BRCA1 siRNA HeLa cells that were untreated or exposed to IR (10 Gy) or MMC (500 ng/mL) as indicated and immunoprecipitated with FANCJ antibody. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-RPA70 (bottom) antibodies. (C) HCC 1937 cells form RPA but not FANCJ DNA damage-inducible foci. BRCA1 mutant HCC 1937 or reconstituted cells were treated with the DNA-damaging agent MMC (500 ng/mL) or exposed to 10 Gy IR as described in “Immunofluorescence cellular localization studies.” After fixation and permeabilization, cells were incubated with anti-RPA (green) and anti-FANCJ (red) antibodies. (D) Quantitation of FANCJ-RPA colocalizing foci as described in panel C. Percentages of RPA foci colocalizing with FANCJ are represented (□). Percentages of FANCJ foci colocalizing with RPA are represented (▩). Experimental data are the mean of at least 3 independent experiments with SD indicated by error bars.

Effect of BRCA1 deficiency on the DNA damage-inducible association of FANCJ and RPA in BRCA1-deficient cells. (A) siRNA depletion of BRCA1. WCE of HeLa cells transfected with control or BRCA1 siRNA were probed using an antibody against BRCA1. Actin serves as a loading control. (B) WCEs were prepared from control siRNA or BRCA1 siRNA HeLa cells that were untreated or exposed to IR (10 Gy) or MMC (500 ng/mL) as indicated and immunoprecipitated with FANCJ antibody. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-RPA70 (bottom) antibodies. (C) HCC 1937 cells form RPA but not FANCJ DNA damage-inducible foci. BRCA1 mutant HCC 1937 or reconstituted cells were treated with the DNA-damaging agent MMC (500 ng/mL) or exposed to 10 Gy IR as described in “Immunofluorescence cellular localization studies.” After fixation and permeabilization, cells were incubated with anti-RPA (green) and anti-FANCJ (red) antibodies. (D) Quantitation of FANCJ-RPA colocalizing foci as described in panel C. Percentages of RPA foci colocalizing with FANCJ are represented (□). Percentages of FANCJ foci colocalizing with RPA are represented (▩). Experimental data are the mean of at least 3 independent experiments with SD indicated by error bars.

We examined the breast cancer cell line HCC 1937 and its corrected counterpart for FANCJ and RPA staining. HCC 1937 cells are characterized by a mutant BRCA1 species with a truncated C-terminal region affecting the integrity of the second BRCT motif and defective in the interaction with FANCJ.23 In untreated cells as well as HCC 1937 cells exposed to IR or MMC, most cells displayed poor immunofluorescent staining for FANCJ, whereas the reconstituted BRCA1-positive cells displayed normal FANCJ staining (Figure 5C), consistent with an earlier observation by Cantor et al.7 Thus, although RPA foci form well after DNA damage in the breast cancer HCC 1937 cells, FANCJ foci formation is defective. DNA damage-inducible RPA foci were detected in the HCC 1937 cells (Figure 5C), consistent with an earlier observation.24 These results suggest that BRCA1 status affects FANCJ foci formation with its protein partner RPA after DNA damage. FANCJ and RPA colocalized in the reconstituted HCC 1937 cells after IR or MMC (Figure 5C,D).

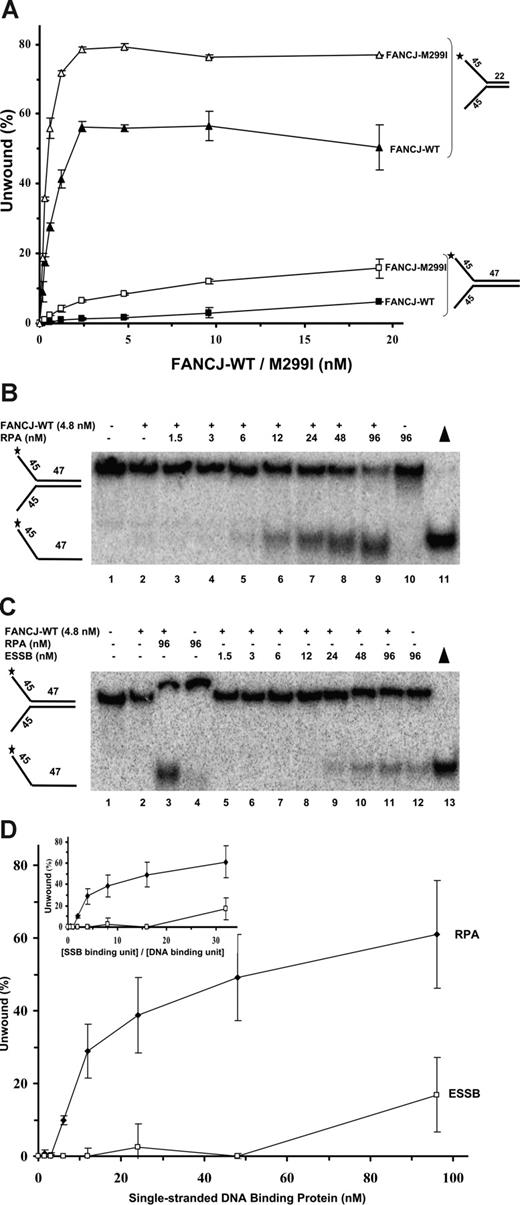

Effect of duplex length on FANCJ helicase activity

To elucidate whether RPA may serve as an auxiliary factor for FANCJ, we examined the ability of FANCJ to unwind preferred forked duplexes of either 22 bp or a longer 47 bp. FANCJ-WT unwound a proportionately greater percentage of the 22-bp forked duplex with increasing protein concentration, achieving approximately 55% of the substrate unwound at 2.4 nM FANCJ-WT (Figure 6A). In comparison, very little (∼1%) of the 47-bp forked duplex was unwound by FANCJ-WT (4.8 nM) and only approximately 6% was unwound by 19.2 nM FANCJ. These results indicate that FANCJ-WT poorly unwinds the 47-bp forked duplex substrate under multiple turnover conditions and suggests that the helicase is not processive.

Limited unwinding reaction catalyzed by FANCJ is stimulated by RPA. (A) FANCJ helicase catalyzes a limited unwinding reaction. Helicase assays were as described,14 using the indicated concentrations of FANCJ-WT or FANCJ-M299I and forked duplex DNA substrates of 22 bp and 47 bp. Incubation was at 30°C for 15 minutes. Reaction products were analyzed by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis. Quantitation of results from helicase assays with standard deviations indicated by error bars. FANCJ-WT, 22 bp, ▲; FANCJ-M299I, 22 bp, △; FANCJ-WT, 47 bp, ■; FANCJ-M299I, 47 bp, □. Percentage of displacement is expressed as a function of FANCJ-WT or FANCJ-M299I protein concentration. (B-D) Stimulation of FANCJ-WT helicase activity by RPA. FANCJ-WT protein (4.8 nM) was incubated with the 47-bp forked duplex in the presence of the indicated concentrations of RPA heterotrimer (B) or ESSB homotetramer (C) under standard helicase reaction conditions. Incubation was at 30°C for 60 minutes. (D) Quantitation of results from helicase assays with SD indicated by error bars. Percentage of displacement is expressed as a function of single-stranded DNA-binding protein concentration (RPA heterotrimer or ESSB homotetramer). (Inset) Quantitation of results with percentage of displacement expressed as a function of the ratio (SSB binding unit)/(DNA-binding unit).

Limited unwinding reaction catalyzed by FANCJ is stimulated by RPA. (A) FANCJ helicase catalyzes a limited unwinding reaction. Helicase assays were as described,14 using the indicated concentrations of FANCJ-WT or FANCJ-M299I and forked duplex DNA substrates of 22 bp and 47 bp. Incubation was at 30°C for 15 minutes. Reaction products were analyzed by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis. Quantitation of results from helicase assays with standard deviations indicated by error bars. FANCJ-WT, 22 bp, ▲; FANCJ-M299I, 22 bp, △; FANCJ-WT, 47 bp, ■; FANCJ-M299I, 47 bp, □. Percentage of displacement is expressed as a function of FANCJ-WT or FANCJ-M299I protein concentration. (B-D) Stimulation of FANCJ-WT helicase activity by RPA. FANCJ-WT protein (4.8 nM) was incubated with the 47-bp forked duplex in the presence of the indicated concentrations of RPA heterotrimer (B) or ESSB homotetramer (C) under standard helicase reaction conditions. Incubation was at 30°C for 60 minutes. (D) Quantitation of results from helicase assays with SD indicated by error bars. Percentage of displacement is expressed as a function of single-stranded DNA-binding protein concentration (RPA heterotrimer or ESSB homotetramer). (Inset) Quantitation of results with percentage of displacement expressed as a function of the ratio (SSB binding unit)/(DNA-binding unit).

A naturally occurring FANCJ-M299I sequence variant with an amino acid substitution in the conserved iron-sulfur cluster of the helicase domain10 displayed a significantly elevated ATPase activity compared with FANCJ-WT.25 We tested whether the elevated ATPase activity of FANCJ-M299I enabled it to unwind longer DNA substrates. FANCJ-M299I unwound a proportionately greater percentage of the 22-bp forked duplex with increasing protein concentrations; however, FANCJ-M299I was more active than FANCJ-WT at all concentrations tested (Figure 6A). For example, approximately 55% of the 22-bp forked duplex substrate was unwound at 0.6 nM FANCJ-M299I, whereas only 27% of the 22-bp substrate was unwound by 0.6 nM FANCJ-WT, consistent with our previous studies that FANCJ-M299I is more active than FANCJ-WT.25

We next evaluated the ability of FANCJ-M299I to unwind the 47-bp forked duplex. Only 2% of the substrate was unwound at 0.6 nM FANCJ-M299I (Figure 6A). Nonetheless, FANCJ-M299I was clearly able to unwind a greater percentage of the 47-bp substrate than FANCJ-WT, achieving approximately 9% substrate unwound at 4.8 nM FANCJ-M299I (Figure 6A). The 47-bp forked duplex was efficiently wound by E coli DNA TraI helicase (R.G. and R.M.B., unpublished data, June 2006), indicating that the substrate can be unwound under FANCJ helicase reaction conditions. These results suggest that FANCJ-M299I unwinds both short and long duplex tracts better than FANCJ-WT; however, even a relatively short duplex length of 47 bp prevents FANCJ-M299I from efficiently unwinding a great percentage of the forked DNA substrate.

Effect of single-stranded DNA-binding proteins on FANCJ helicase activity

We tested FANCJ-WT helicase activity on the 47-bp forked duplex in the presence of increasing RPA concentrations (Figure 6B-D). FANCJ-WT was stimulated by RPA to unwind the 47-bp substrate. At the highest concentration of RPA tested (96 nM), approximately 60% of the substrate was unwound. In comparison, there was little to no detectable unwinding of the DNA substrate by FANCJ-WT in the absence of RPA. To determine whether the stimulation of FANCJ-WT helicase activity by RPA was specific, we evaluated the effect of ESSB on the unwinding reaction catalyzed by FANCJ-WT. ESSB concentrations up to 48 nM homotetramer failed to stimulate FANCJ-catalyzed unwinding of the 47-bp forked duplex (Figure 6C,D). In contrast, 50% of the 47-bp substrate was unwound by FANCJ in the presence of 48 nM RPA heterotrimer (Figure 6B). The only stimulatory effect of ESSB on FANCJ helicase activity was observed at the highest concentration tested (96 nM), which was markedly less than that observed for RPA (Figure 6C,D). ESSB efficiently bound the 47-bp forked duplex substrate under the FANCJ helicase reaction conditions in gel-shift assays (data not shown), indicating that the poor ability of ESSB to stimulate FANCJ helicase was not simply attributed to its inability to bind ssDNA.

To gain insight into the mechanism of stimulation of FANCJ-WT helicase activity by RPA, strand displacement was expressed as a function of the ratio (R) of SSB-binding units per DNA-binding site. This analysis takes into account that 1 ESSB homotetramer binds 35 nt,26 and 1 hRPA heterotrimer binds 30 nt.27 Stimulation of FANCJ helicase activity on the 47-bp forked duplex substrate was first detectable at a 2-fold excess of RPA heterotrimer binding units compared with ssDNA-binding sites for RPA (R = 2) (Figure 6D inset). Approximately 30% of the 47-bp substrate was unwound at an R value of 4. At an R value of 16, the RPA-stimulated FANCJ unwinding reaction attained a value of 48% substrate unwound. In contrast, ESSB failed to stimulate FANCJ helicase at a 16-fold excess of ESSB binding equivalents compared with ESSB-binding sites (Figure 6D inset). An effect of ESSB on FANCJ helicase activity was only detected at a 32-fold excess of ESSB binding units compared with ESSB binding site. Because ESSB so poorly stimulated FANCJ unwinding of the 47-bp duplex substrate suggests that a specific interaction between FANCJ helicase and RPA is responsible for the observed unwinding of the DNA substrate. Furthermore, these results suggest that the stimulation of FANCJ helicase activity by RPA does not only reflect a ssDNA-coating effect of RPA because it was observed that at similar ratios of SSB protein binding equivalents to SSB binding sites, ESSB failed to stimulate FANCJ-WT helicase activity, whereas RPA clearly stimulated DNA unwinding by FANCJ-WT.

We measured the effect of RPA on ssDNA-stimulated ATPase activity of FANCJ. There was no detectable stimulation of FANCJ ATPase activity at all tested RPA concentrations (24-192 nM) (data not shown).

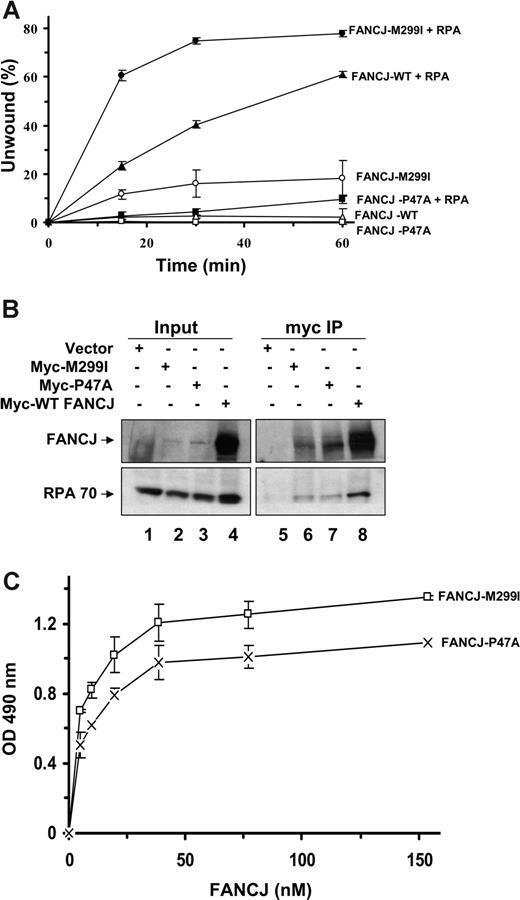

Kinetic comparison of DNA unwinding by FANCJ and sequence variants

We performed kinetic analyses of DNA unwinding reactions catalyzed by FANCJ-WT and its associated polymorphic variants in the presence or absence of RPA (Figure 7A). As expected, in the absence of RPA FANCJ-WT poorly unwound the 47-bp forked duplex during the entire time course. In the presence of RPA, an increasing percentage of the substrate was unwound by FANCJ-WT that was proportional to the time of incubation. When RPA was present, 60% of the 47-bp substrate was unwound by FANCJ-M299I at 15 minutes compared with only 22% substrate unwound by FANCJ-WT. A second naturally occurring polymorphic variant in the ATPase domain, designated FANCJ-P47A, was seriously compromised in its ability to unwind the 47-bp forked duplex in the absence of RPA; however, nearly 10% of the substrate was unwound by FANCJ-P47A in reactions containing RPA (Figure 7A). Thus, FANCJ-P47A helicase activity is stimulated by RPA, but not nearly to the level of unwinding exhibited by FANCJ-WT. However, FANCJ-M299I helicase activity shows an increased rate of DNA unwinding compared with FANCJ-WT in the absence or presence of RPA.

Kinetic analyses of DNA unwinding of the 47-bp forked duplex DNA substrate by FANCJ-WT or FANCJ polymorphic variants in the presence of RPA or ESSB. (A) FANCJ-WT (4.8 nM) or its associated variants (FANCJ-M299I or FANCJ-P47A) was incubated with the 47-bp forked duplex in the absence or presence of 24 nM RPA heterotrimer under standard helicase reaction conditions. Incubation was at 30°C for the indicated times. Quantitation of results from helicase assays with SD are indicated by error bars. FANCJ-WT (△); FANCJ-WT + RPA (▲); FANCJ-M299I (○); FANCJ-M299I + RPA (●); FANCJ-P47A (□); FANCJ-P47A + RPA (■).(B) Coimmunoprecipitation of FANCJ (FANCJ) sequence variants with RPA. FA-J cells were transiently transfected with plasmid DNA encoding Myc-tagged FANCJ-WT, FANCJ-M299I, or FANCJ-P47A, and WCEs were used for coimmunoprecipitation experiments using FANCJ antibody. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-RPA (bottom) antibodies. Input represents 15% of WCE input for coimmunoprecipitation experiments. (C) RPA directly binds to FANCJ variants. RPA (96 nM heterotrimer) was coated onto the ELISA plate. After blocking with 3% BSA, the wells were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified recombinant FANCJ-M299I or FANCJ-P47A protein (0-150 nM) for 60 minutes at 37°C. Wells were aspirated and washed 3 times, and bound FANCJ protein was detected by ELISA using a rabbit polyclonal antibody against FANCJ.

Kinetic analyses of DNA unwinding of the 47-bp forked duplex DNA substrate by FANCJ-WT or FANCJ polymorphic variants in the presence of RPA or ESSB. (A) FANCJ-WT (4.8 nM) or its associated variants (FANCJ-M299I or FANCJ-P47A) was incubated with the 47-bp forked duplex in the absence or presence of 24 nM RPA heterotrimer under standard helicase reaction conditions. Incubation was at 30°C for the indicated times. Quantitation of results from helicase assays with SD are indicated by error bars. FANCJ-WT (△); FANCJ-WT + RPA (▲); FANCJ-M299I (○); FANCJ-M299I + RPA (●); FANCJ-P47A (□); FANCJ-P47A + RPA (■).(B) Coimmunoprecipitation of FANCJ (FANCJ) sequence variants with RPA. FA-J cells were transiently transfected with plasmid DNA encoding Myc-tagged FANCJ-WT, FANCJ-M299I, or FANCJ-P47A, and WCEs were used for coimmunoprecipitation experiments using FANCJ antibody. The blot was probed with rabbit anti-FANCJ (top) and mouse anti-RPA (bottom) antibodies. Input represents 15% of WCE input for coimmunoprecipitation experiments. (C) RPA directly binds to FANCJ variants. RPA (96 nM heterotrimer) was coated onto the ELISA plate. After blocking with 3% BSA, the wells were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified recombinant FANCJ-M299I or FANCJ-P47A protein (0-150 nM) for 60 minutes at 37°C. Wells were aspirated and washed 3 times, and bound FANCJ protein was detected by ELISA using a rabbit polyclonal antibody against FANCJ.

To evaluate whether RPA interacts with FANCJ variants, we performed anti-Myc coimmunoprecipitation experiments from lysates of FA-J cells transfected with the corresponding Myc-tagged wild-type or FANCJ variant (Figure 7B). Expression of the M299I or P47A mutant protein was reduced compared with FANCJ-WT, as shown by the input. However, RPA was coimmunoprecipitated in cells transfected with M299I or P47A, suggesting that RPA is associated with either variant in cell extracts. To determine whether the FANCJ variants can directly bind RPA, we performed ELISA assays with the purified recombinant proteins (Figure 7C). Both M299I and P47A mutant proteins interacted with RPA similar to FANCJ-WT, with Kd values of 5.3 and 7.4 nM, respectively.

Discussion

Understanding the role of FANCJ in cellular DNA metabolism and how FANCJ dysfunction leads to tumorigenesis requires a comprehensive investigation of its catalytic mechanism and molecular functions in DNA repair. In this study, we identified RPA as the first regulatory partner of the FANCJ helicase. We found that RPA localizes with FANCJ in a DNA damage-inducible manner, coprecipitates with FANCJ from nuclear extracts, and stimulates FANCJ helicase activity in a specific manner. A key property of DNA helicases is their ability to unwind long duplexes. Certain DNA helicases (eg, RecBCD,28 TraI29 ) can processively unwind DNA tracts of thousands of base pairs, whereas UvrD helicase only unwinds long DNA duplexes in a protein concentration-dependent manner.30 In contrast, the human RecQ helicases WRN and BLM can only unwind DNA substrates of 100 bp or less in the absence of an auxiliary factor.31 Even on a preferred forked duplex DNA substrate, FANCJ acts inefficiently to unwind a 47-bp duplex, suggesting that FANCJ is specifically tailored to act on short duplex substrates that it might encounter during a process associated with DNA repair or replication restart. Alternatively, FANCJ could be associated with RPA as an accessory factor to facilitate FANCJ unwinding of longer DNA duplexes that is required during cellular DNA metabolic processing events. These two possibilities are not mutually exclusive. Given the potential involvement of FANCJ in more than one aspect of ICL repair with FA proteins as well as DSB repair, it will be of interest to determine the role(s) and DNA unwinding mode(s) of FANCJ in different subcomplexes involved in these pathways.

RPA was identified in a multiprotein nuclear complex (BRAFT) containing 5 FA core complex proteins (A, C, E, F, and G), BLM, and topoisomerase IIIα32 ; however, to our knowledge the assignment of FANCJ to this or any other multiprotein complex is not yet reported. A BRCA1-associated genome surveillance complex containing a number of DNA repair or signaling proteins, including MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, ATM, BLM, and RAD50-MRE11-NBS1, and DNA replication factor C was identified.33 It will be of interest to characterize the functional activities of FANCJ protein complexes. Our results indicate that FANCJ probably resides in a protein subcomplex with RPA.

The functional interaction and mechanism whereby RPA stimulates FANCJ helicase activity is specific as evidenced by the inability of ESSB to enhance FANCJ unwinding. A specific functional interaction between FANCJ and RPA is further supported by our demonstration of their physical interaction mediated by RPA70, a feature that is also characteristic of the interaction of RPA with human RecQ helicases (WRN,34,35 BLM,36 RECQ137 ).

WRN and BLM interact with RPA70 through functionally conserved domains of the helicases that do not display extensive sequence homology.31 The WRN-interacting domain and ssDNA-binding domain of RPA overlap with each other,31,38 suggesting that ssDNA and WRN protein-binding domains of RPA70 are functionally intertwined. In addition to RPA loading a DNA-processing protein such as helicase on to ssDNA, RPA interaction with some helicases may enable them to actively place RPA on ssDNA as it emerges from the helicase complex.39 Protein partners of RPA, such as helicases, may trade places on ssDNA by binding to RPA and mediating conformational changes that alter the ssDNA-binding properties of RPA. The order for sequential loading of FANCJ and RPA to unwind a DNA intermediate is particularly interesting and challenging to decipher because the precise role of FANCJ in the multistep FA pathway is not known.

Formation of the FA core complex and FANCD2 monoubiquitination is intact, suggesting that the FANCJ functions downstream in the FA pathway.11 However, FANCD2 monoubiquitination is required for its association with chromatin and subnuclear localization with BRCA1, RAD51, MRE11-RAD50-NBS1, RPA, PCNA, and BRCA2, suggesting a connection of the upstream and downstream events of the FA pathway in which FANCJ operates.40 Unwinding of a DNA structure associated with a stalled replication fork by FANCJ may enable HR or nonhomologous end-joining repair proteins to access the damaged site and facilitate ICL repair.11 FANCJ recognizes a D-loop structure and catalytically unwinds the invading strand, irrespective of tail status, in vitro.14 This action of FANCJ may be interpreted as a potential hindrance to some aspect of recombinational repair. It is likely that the role of FANCJ in terms of its catalytic function is better understood in the context of its interacting partners, such as RPA which improves its ability to unwind longer DNA duplexes. However, RPA does not enable FANCJ to unwind a Holliday junction (R.G. and R.M.B., unpublished data, April 2006), another key HR intermediate, suggesting that other structure-specific helicases such as the RecQ enzymes,41 are responsible for resolving these structures. The reported direct binding of FANCD2 to Holliday junctions42 may facilitate its subsequent resolution through branch-migrating helicases and resolving enzymes. Understanding how the classic FA proteins prevent replication fork-associated DSBs and maintain genomic stability will require the characterization of functional FA protein interactions and the assembly of models for the pathways from these biochemical findings.

FANCJ and RPA colocalize in nuclear foci after DNA damage and replicational stress, suggesting that they may collaborate with each other and other components of DSB repair to facilitate recombinational repair of frank DSBs or DSBs induced by stalled or arrested replication forks. RPA, but not FANCJ, formed DNA damage-inducible foci in BRCA1 mutant HCC 1937 cells. Thus, although BRCA1 was reported to be associated with RPA after IR treatment,24 FANCJ does not form foci with RPA well after IR or MMC. The importance of BRCA1 for colocalization of FANCJ and RPA after MMC damage is consistent with the hypersensitivity of BRCA1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts to MMC accompanied by defective MMC-induced Rad51 foci and aberrant S-phase arrest.43 Together, these results suggest a role of BRCA1 in HR during S phase to repair MMC-induced ICLs that involve the concerted action of FANCJ and RPA.

Although FANCJ and RPA are associated with each other in FA mutant cell lines, it is possible that FANCJ and RPA function noncooperatively in DNA repair centers that operate when the FA pathway is dysfunctional. FANCJ and RPA may be important for functions independent of the FA core complex. FANCJ helicase activity was shown to be essential for its function in restoring ICL resistance.12 RPA is implicated in signaling at stalled replication forks in which the accumulated ssDNA is bound by RPA, creating a signal for activation of the ATR-dependent checkpoint response.44 In the future, it will be important to address the role of FANCJ interactions with DNA repair factors such as RPA that modulates its catalytic activity to understand its proposed roles in DNA repair or DNA damage signaling that are either dependent or independent of the FA pathway.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund for FA-A (PD220), FA-C (PD331), and FA-D2 (PD20) cells and Dr Hans Joenje (Utrecht Medical Center, the Netherlands) for FA-J EUFA030 cells. We thank Dr Fred Indig (NIA-NIH) for assistance with microscopy.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging.

Authorship

Contribution: R.G. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; S.S. performed research and analyzed data; J.A.S. and M.K.K. contributed valuable reagents; S.B.C. contributed valuable reagents and wrote the paper; and R.M.B. designed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

R.G. and S.S. contributed equally to this study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Robert M. Brosh Jr, Laboratory of Molecular Gerontology, NIA, NIH, 5600 Nathan Shock Drive, Baltimore, MD 21224; e-mail:BroshR@grc.nia.nih.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal