Diverse receptors, including Fcγ receptors and β2 integrins (complement receptor-3 [CR3], CD11b/CD18), have been implicated in phagocytosis, but their distinct roles and interactions with other receptors in particle engulfment are not well defined. CD44, a transmembrane adhesion molecule involved in binding and metabolism of hyaluronan, may have additional functions in regulation of inflammation and phagocytosis. We have recently reported that CD44 is a fully competent phagocytic receptor that is able to trigger ingestion of large particles by macrophages. Here, we investigated the role of coreceptors and intracellular signaling pathways in modulation of CD44-mediated phagocytosis. Using biotinylated erythrocytes coated with specific antibodies (anti-CD44–coated erythrocytes [Ebabs]) as the phagocytic prey, we determined that CD44-mediated phagocytosis is reduced by 45% by a blocking CD11b antibody. Further, CD44-mediated phagocytosis was substantially (42%) reduced in CD18-null mice. Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that CD11b is recruited to the phagocytic cup. The mechanism of integrin activation and mobilization involved activation of the GTPase Rap1. CD44-mediated phagocytosis was also sensitive to the extracellular concentration of the divalent cation Mg2+ but not Ca2+. In addition, buffering of intracellular Ca2+ did not affect CD44-mediated phagocytosis. Taken together, these data suggest that CD44 stimulation induces inside-out activation of CR3 through the GTPase Rap1.

Introduction

Complement receptor-3 (CR3, Mac1, CD11b/CD18) is a member of the β2 integrin family of adhesion receptors, which includes CR4 (CD11c/CD18) and LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18). These heterodimeric transmembrane receptors, composed of an α chain (CD11a, CD11b, or CD11c) and the common β2 chain (CD18), are expressed exclusively on cells of hematopoietic origin. CR3 is multifunctional and is known to be involved in leukocyte adhesion, diapedesis, and phagocytosis.1 Unlike phagocytosis mediated by Fc receptors, CR3-mediated phagocytosis is regulated by the activation state of the receptor. On quiescent (resting) leukocytes and monocytes, CR3 is capable of binding but not ingesting iC3b-coated phagocytic prey. In contrast, prior activation of leukocytes by diverse agents such as phorbol ester2 and extracellular matrix proteins such as fibrinogen3,–5 activates CR3 and renders it capable of particle ingestion (phagocytosis).

While many studies of phagocytosis have used artificial particles such as erythrocytes or latex beads opsonized with monospecific ligands as phagocytic prey, microbial pathogens such as bacteria and fungi express multiple ligands on their cell surfaces that can be recognized by phagocytes.6,7 The simultaneous engagement of multiple receptors on the host cell by the pathogen ensures that diverse cellular signaling pathways are activated, and the resultant cellular response will therefore reflect a composite of the effects of activation of the different receptors. Examples of cross-talk between receptors include activation of CR3, other complement receptors, mannose receptors, and scavenger receptors by pathogens such as Leishmania donovani8,–10 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.11,12 Previous studies have provided evidence that FcγR-derived signals induce activation of CR3.13,14 Specifically, FcγR stimulation in macrophages promotes CR3 clustering into high-avidity complexes in phagocytotic cups by a mechanism involving release of integrins from their cytoskeletal constraints, thus enhancing their lateral diffusion.14

CD44 is a transmembrane receptor involved in the binding and metabolism of hyaluronan. We have recently reported that CD44 is also a bona fide phagocytic receptor15 effective at recognition and ingestion of hyaluronan-coated and anti-CD44 antibody–coated phagocytic prey. Other reports have implicated CD44 in the host response to bacterial infection.16,,–19 For example, CD44-deficient mice display enhanced pulmonary inflammation in response to Escherichia coli pneumonia, possibly related to defective neutrophil or macrophage function.20 In addition, lipopolysaccharide treatment induces enhanced surface expression of CD44 in human monocytes by a c-Jun N-terminal kinase–dependent pathway.21 Components of the bacterial cell wall are also known to up-regulate the expression of Fcγ and CR3 receptors,22,23 leading to enhanced phagocytic efficiency.

CD44 is also known to interact with the β2 integrin LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18) in lymphocytes24,–26 and in colon cancer cells,27 and with β1 integrins in human gastric adenocarcinoma and colorectal cancer cells.28 Monoclonal antibodies directed against CD44 induce lymphocyte aggregation by increasing the avidity of LFA-1 integrins to ICAM-1.26 However, whether CD44 can modulate the activation state of other integrins such as CD11b (CR3) is unknown.

In this study, we sought to define whether CD44 functionally interacts with CR3 and modulates phagocytosis. To accomplish this, we studied the role of CR3 in phagocytosis of anti-CD44–coated erythrocytes (Ebabs) in macrophages. We explored whether direct physical interactions occur between CR3 and CD44, and considered the possibility that CD44 engagement leads to inside-out activation of CR3.

Materials and methods

Approval for this study was obtained from the University of Toronto Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell culture

RAW 264.7 cells (American Type Tissue Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured in DMEM with 4 mM l-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). CD44−/−29 and CD18−/− mice30 were generated as previously described. The double knockouts were obtained by mating CD18- and CD44-null mice. The double knockouts were genotyped and shown to lack expression of both CD18 and CD44 protein as determined by Western blot analysis (not illustrated). Resident peritoneal macrophages from these mice were isolated, plated on glass coverslips, and cultured in DMEM. The next day, cells were washed and prepared for phagocytosis as detailed in “Phagocytosis assay of Ebabs.”

Construction of Ebabs as phagocytic prey

Anti-CD44–coated prey were constructed as recently reported15 according to the method of Hoffman et al.31 Briefly, erythrocytes were incubated with EZ-Link-Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were then incubated with ExtrAvidin (Sigma-Aldrich Canada, Oakville, ON) for 30 minutes. Finally, the cells were incubated with biotinylated rat anti-mouse CD44 (clone: IM7) or rat nonimmune isotype matched IgG2b (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) for 1 hour at 37°C. IgG- and iC3b-coated prey were constructed in an analogous manner.15 Briefly, 100 μL sheep erythrocytes (10% solution; Cappel, West Chester, PA) was incubated with 2 μL rabbit anti-sheep erythrocyte IgG (Cappel) for 1 hour. For the iC3b-coated prey, 100 μL sheep erythrocytes (10% solution; Cappel) was incubated with 40 μL rabbit anti-sheep erythrocyte IgM (Cedarlane Laboratories, Hornby, ON) for 1 hour at 37°C on a rotator. To induce complement activation, the cells were incubated in 33% C5-deficient human serum/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution (Sigma-Aldrich Canada).

Phagocytosis assay of Ebabs

RAW 264.7 or primary murine macrophages were cultured in 6-well plates on 25-mm acid-washed glass coverslips. The cells were washed twice with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) followed by addition of the phagocytic prey at a ratio of 20:1 and allowed to interact and bind to the macrophages for 5 minutes at 37°C. The coverslips were washed to remove unbound prey and incubated at 37°C for an additional 15 minutes to allow phagocytosis to proceed. The assays were terminated by cooling the cells and by washing with ice-cold PBS (calcium- and magnesium-free). The phagocytic efficiency was quantified as the phagocytic index (number of prey ingested per 100 cells).

Phagocytosis of iC3b-coated erythrocytes required preincubation of the phagocytes with 100 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma-Aldrich Canada) for 10 minutes to facilitate adhesion. Following incubation, hypotonic lysis of the extracellular erythrocytes was achieved by addition of water for 30 seconds, followed by immediate replacement with calcium- and magnesium-free PBS. The coverslips were mounted on Attofluor cell chambers (Invitrogen Canada, Burlington, ON), and quantification of phagocytosis was conducted using a Leica DMIRB inverted microscope equipped with a 100×/1.3 NA oil-immersion objective lens (Leica Microsystems, Jena, Germany).

Divalent cation chelation

EDTA and EGTA (Sigma-Aldrich Canada) were used to chelate divalent cations. In the first set of experiments (Figure 1A-C), the HBSS used contained 1.5 mM of the divalent cations Ca2+ and Mg2+ with traces of Mn2+ (denoted as HBSS+/+). A 3-mM solution of either EDTA or EGTA was made using the HBSS+/+ solution with the pH adjusted to 7.4. Phagocytosis was allowed to proceed as described with the cells suspended in HBSS containing 3 mM EDTA or EGTA as indicated. Where indicated, cells were pretreated with the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump inhibitor thapsigargin (Sigma-Aldrich Canada) for 10 minutes in HBSS+/+ solution.

In the second set of experiments (Figure 1D), phagocytosis was studied in HBSS solution without added Ca2+ or Mg2+ and containing 0.5 mM EDTA (denoted HBSS−/−). Where indicated, 2 mM Ca2+, Mg2+, or Mn2+ (Sigma-Aldrich Canada) were added to the HBSS−/− solution. As EDTA and divalent cations form a 1:2 complex, these conditions will result in a concentration of free cation of 1.0 mM. Phagocytosis was studied under these conditions. Control experiments were done in HBSS+/+ and HBSS+/+ containing 3 mM EDTA.

Neutrophil isolation and rosetting assay

Human neutrophils were isolated from whole blood obtained by venipuncture and anticoagulated with citrate. Dextran sedimentation and discontinuous plasma-Percoll gradients were used as previously described.32 Neutrophils were resuspended in HBSS+/+ and then stimulated with 100 nM PMA for 15 minutes. Cells were subsequently incubated for 20 minutes with iC3b-coated prey. The neutrophils were then cytocentrifuged (Shandon CytoSpin II; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to a glass slide and stained with Hemacolor according to manufacturer's instructions (EMD Chemicals, San Diego, CA). The cells were then examined by light microscopy and images acquired using a Leica DMRA2 fluorescent microscope equipped with a 63×/1.32 oil immersion objective lens and the standard filter sets (Leica Microsystems). Digital images were acquired through a Qimaging Retiga EX camera (Qimaging, Burnaby, BC) and processed using OpenLab 4.0 software (Improvision, Lexington, MA).

Hyaluronan modulation of CR3-mediated phagocytosis

Cells were plated on glass coverslips the day prior to the experiments. Cells were washed twice with PBS then resupended in HBSS. Cells were pretreated with either PMA (100 nM; Sigma-Aldrich Canada) or hyaluronan (15 μg/mL, 150 μg/mL, or 1.5 mg/mL rooster comb hyaluronan; Sigma-Aldrich Canada) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Following pretreatment, the iC3b phagocytosis assay was allowed to proceed as described in “Phagocytosis assay of Ebabs.”

Blocking CR3 and effects of phorbol ester treatment

A total of 5 μg/mL anti-CD11b or isotype control antibodies (BD Biosciences Pharmingen; clone: M1/70) was preincubated with the RAW cells 30 minutes prior to phagocytosis. The cells were washed, and phagocytosis was allowed to proceed as described (Figure 2A). Where indicated, (Figure 6A,B), cells were pretreated with various concentrations of PMA as indicated (Sigma-Aldrich Canada) for 20 minutes prior to phagocytosis.

Immunoprecipitation

The cells were lysed in a Tris-containing buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 1% Triton X-100, 120 mM NaCl, 1% aprotinin, 1 mM PMSF, and Roche cocktail mini protease inhibitor). The cell lysates were subject to centrifugation at 16 000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was precleared with Pansorbin A (Sigma-Aldrich Canada) for 10 minutes at 4°C, followed by addition of anti-CD44 or anti-CD18 antibody (1 μg/100 μg of protein; BD Biosciences Pharmingen) and incubated for 1 hour at 4°C. Subsequently, 50 μL of prewashed protein A/G–Sepharose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were added to the supernatant and incubated over night at 4°C. The beads were washed twice and proteins were eluted by boiling in nonreducing Laemmli sample buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Whole-cell lysates and CD44 and CD18 immunoprecipitates were blotted with anti-CD44 and anti-CD18 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) antibodies. In some experiments, the specified receptor was cross-linked with primary biotinylated antibodies (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) and secondary avidin (Sigma-Aldrich Canada) for 10 minutes each prior the lysis (Figure 3A).

Immunofluorescence

Colocalization studies were conducted in RAW macrophages stained with biotinylated anti-CD44 for 20 minutes on ice followed by avidin-Cy3 (Sigma-Aldrich Canada) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (Canemco, Saint Laurent, QC) and stained with anti-CD11b Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (BD Biosciences Pharmingen). Quiescent cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, then stained with biotinylated anti-CD44 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) followed by avidin-CY3 (Sigma-Aldrich Canada) and addition of anti-CD11b Alexa Fluor 488 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen). CD11b recruitment to the CD44 phagocytic cup was performed on RAW cells using an anti-CD11b Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated antibody for 20 minutes on ice. Cells were warmed to 37°C, CD44 Ebabs were allowed to settle on the macrophages, and phagocytosis was allowed to proceed. The cells were then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and mounted on a slide using Dako mounting medium (Dako Canada, Mississaga, ON). Fluorescent images were captured using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope equipped with a 100 ×/1.4 oil immersion objective lens, standard laser lines, and filter sets. Digital images were processed with LSM acquisition software v.3.2.

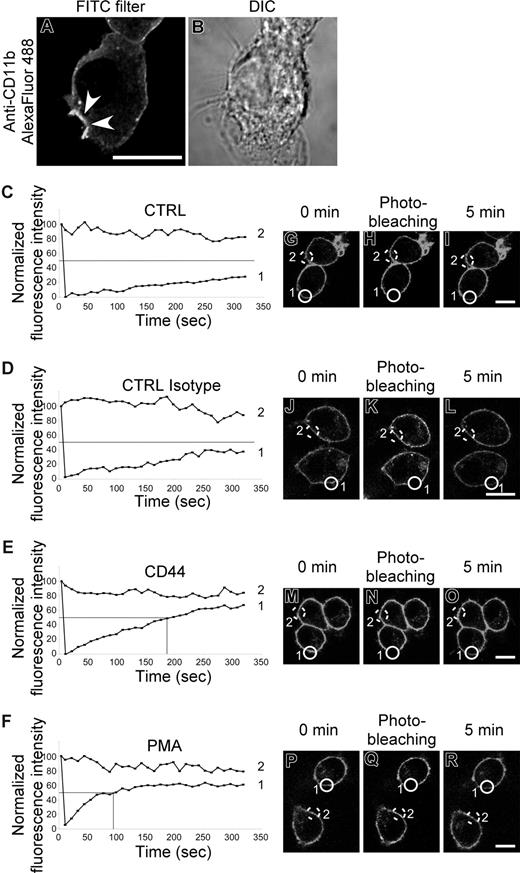

CD11b photobleaching

RAW macrophages were preincubated with Alexa Fluor 488–labeled CD11b (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) for 30 minutes on ice. Fluorescence recovery of the photobleached area was compared in resting cells and in cells treated with PMA (100 nM; Sigma-Aldrich Canada), isotype control, and CD44 antibody (BD Biosciences Pharmingen). Primary biotinylated antibodies or PMA were added for 10 minutes on ice. The cells were warmed to 37°C, and avidin was added. Photobleaching occurred immediately after the addition of the avidin (Sigma-Aldrich Canada), and the fluorescence recovery was recorded for 5 minutes. At least 2 cells were analyzed per experiment, 1 for control and 1 subject to photobleaching. Fluorescent images were captured using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope equipped with a 100×/1.4 oil immersion objective lens, standard laser lines, and filter sets. Digital images were processed with LSM acquisition software v.3.2.

Flow cytometry

The CD11b expression was measured by plating RAW macrophages on 5-cm Petri dishes the day prior to the experiment. Fluorescent pink amino functional latex beads (Spherotech, Libertyville, IL) were coated with 200 μg/mL hyaluronan (Sigma-Aldrich Canada) in PBS rotating for 1 hour at room temperature. The cells were washed twice with HBSS containing HEPES and then incubated with the fluorescent beads (ratio of 5:1) for 45 minutes at 37°C. The dishes were washed with cold PBS and CR3 was stained with Alexa Fluor 488 anti-CD11b (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) for 15 minutes at 4°C. The cells were then scraped and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACScan; Becton Dickinson, Palo Alto, CA). Controls included cells that had ingested fluorescent beads and then stained using an irrelevant isotype matched Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated antibody. The fluorescent beads allowed us to separate the cells that phagocytosed or bound a prey from the cells that had not.

Human peripheral blood was obtained by venipuncture, and erythrocytes were lysed with hypotonic saline for 30 seconds. The remaining cells were washed and then incubated with 5 μg/mL CD44 or isotype control antibody (5 minutes at 4°C; BD Biosciences Pharmingen) followed by addition of a secondary (cross-linking) antibody (5 μg/mL for 10 minutes at 37°C; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). PMA (1 μM; Sigma-Aldrich Canada) was used as a positive control, and unstimulated cells were used as a negative control. The cells were then fixed using fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) lysis solution (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were incubated for 1 hour with a FITC-conjugated CR3 antibody (eBioscience, San Diego, CA; clone: CBRM1/5) that recognizes the high-affinity state of human CR3. Cells were washed twice and resuspended in PBS. The fluorescence intensity of the monocyte population, the latter determined by side and forward light-scattering properties, was evaluated by flow cytometry (FACScan) as a measure of the CR3 high-affinity state.

Rap1 activation

The level of activated Rap1 was determined using a “pull-down” assay as previously described.33 Briefly, GST-RAL–transformed bacteria were grown to an optical density of 0.6. Bacteria were lysed (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, and Roche complete mini protease inhibitor) and GST-RAL–purified using glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich Canada). RAW cells were stimulated with 5 μg/mL CD44 or isotype control antibody (5 minutes at 4°C; BD Biosciences Pharmingen), followed by cross-linking with secondary antibody (5 μg/mL for 10 minutes at room temperature; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). PMA (1 μM) was used as a positive control. The cells were lysed (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% NP40, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and Roche complete mini protease inhibitor), and then 500 μg of cell lysate was added to 500 μg of GST-RAL prebound to glutathione agarose beads and rotated for 2 hours at 4°C. The preparations were subject to centrifugation at 50g and washed 5 times. The pellets were resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer. Western blotting with anti-Rap1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was then performed.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc analysis by Turkey-Kramer using StatView (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was considered for P values less than .05. Densitometry analysis was performed using National Institutes of Health (NIH) Image J (version 1.47; Bethesda, MD). The Western blots were scanned with an optical scanner (AGFA DuoScan f40) using the software provided by the manufacturer (AGFA Canada, Toronto, ON).

Results

Sensitivity of CD44 phagocytosis to divalent cation

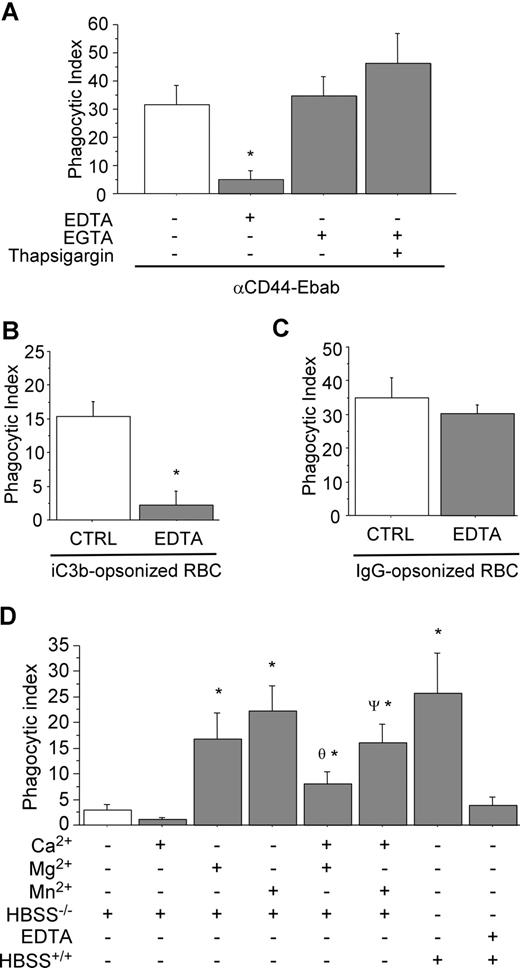

To elucidate the importance of divalent cations in CD44-mediated phagocytosis, RAW cells were incubated in medium containing either EDTA or EGTA prior to and during phagocytosis. The EDTA-based solution was used to chelate divalent cations, including Mg2+, Ca2+, Mn2+, and Zn2+. As illustrated in Figure 1A, CD44-mediated phagocytosis was strongly inhibited under this condition. By contrast, CD44-mediated phagocytosis proceeded normally in an EGTA-containing solution used here to selectively chelate Ca+2. (It is noteworthy that EGTA preferentially binds Ca+2 with a significantly greater affinity than the other divalent cations.) These results indicate that extracellular Ca2+ is not required for CD44-mediated phagocytosis. For comparison, Fcγ- and CR3-mediated phagocytosis were also studied in presence of EDTA (Figure 1B,C). These experiments revealed that CR3-mediated phagocytosis was highly sensitive to the presence of EDTA, while Fcγ-mediated phagocytosis was not, confirming previous reports.34

CD44-mediated phagocytosis is magnesium dependent. (A) CD44 phagocytosis was assessed in the presence of the divalent cation chelators EDTA or EGTA (3 mM) or thapsigargin (10 μM) as indicated. * indicates significantly different from the other conditions (P < .05). Data are shown as the means plus or minus standard error (SE); n = 6. (B,C) Control experiments examining CR3-mediated phagocytosis (B) and Fcγ-mediated phagocytosis (C) in the presence or absence of 3 mM EDTA. * indicates different from the other (P < .05). Data are shown as the means plus or minus SE; n = 6. (D) Efficiency of CD44-mediated phagocytosis in the presence of individual divalent cations. * indicates different from buffer control; θ different from (HBSS−/− + Mg2+); ψ different from (HBSS−/− + Mn2+) (P < .05). Data are shown as the means plus or minus SE; n = 6.

CD44-mediated phagocytosis is magnesium dependent. (A) CD44 phagocytosis was assessed in the presence of the divalent cation chelators EDTA or EGTA (3 mM) or thapsigargin (10 μM) as indicated. * indicates significantly different from the other conditions (P < .05). Data are shown as the means plus or minus standard error (SE); n = 6. (B,C) Control experiments examining CR3-mediated phagocytosis (B) and Fcγ-mediated phagocytosis (C) in the presence or absence of 3 mM EDTA. * indicates different from the other (P < .05). Data are shown as the means plus or minus SE; n = 6. (D) Efficiency of CD44-mediated phagocytosis in the presence of individual divalent cations. * indicates different from buffer control; θ different from (HBSS−/− + Mg2+); ψ different from (HBSS−/− + Mn2+) (P < .05). Data are shown as the means plus or minus SE; n = 6.

We next studied the role of the individual divalent cations Ca2+, Mg2+, and Mn2+. Using medium supplemented with these cations alone or in combination, we observed that CD44-mediated phagocytosis was highly sensitive to the presence of Mg2+ and Mn2+ in the extracellular medium (Figure 1D). By contrast, depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores using thapsigargin did not influence CD44-mediated phagocytosis (Figure 1A). Interestingly, inclusion of Ca2+ in the buffer resulted in modest inhibition of CD44-mediated phagocytosis (similar results were obtained with Fcγ-mediated phagocytosis; data not shown). Further, the presence of extracellular Ca2+ antagonized the effects of Mg2+ or Mn2+ alone (Figure 1D). Taken together, these observations provide strong evidence that CD44-mediated phagocytosis is dependent on the presence of extracellular Mg2+ or Mn2+, but not extracellular Ca2+.

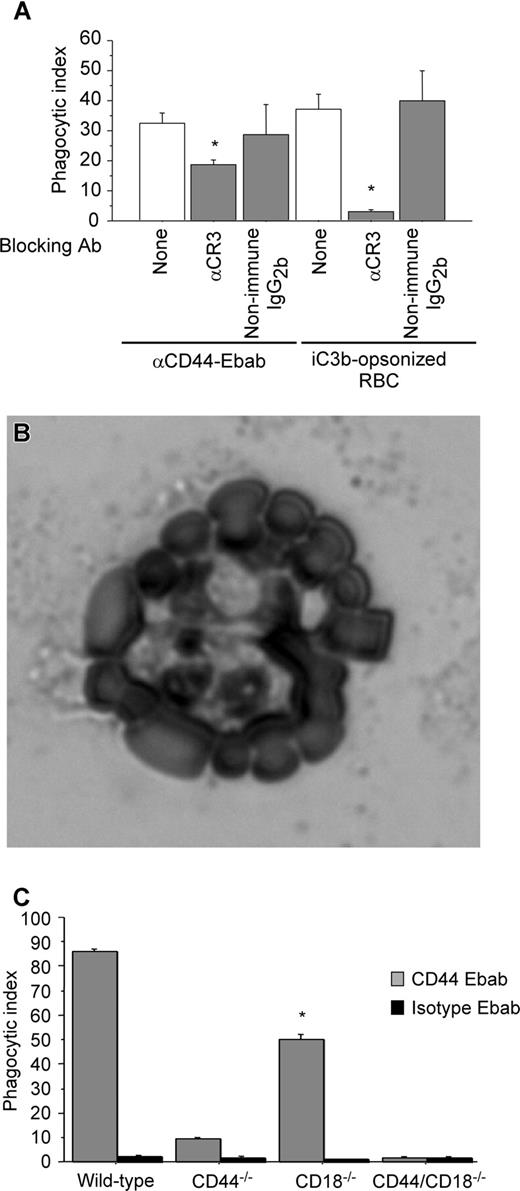

CR3-blocking antibody decreases CD44-mediated phagocytosis

We next sought to determine the mechanism by which Mg2+ regulated CD44-mediated phagocyosis. As there is no evidence of a direct action of Mg2+ on CD44 function, we considered a possible role of the β2 integrin CR3 in CD44-mediated phagocytosis because of the known Mg2+ sensitivity of integrins. To investigate this hypothesis, we used a blocking antibody against CR3 (CD11b) as a pretreatment and examined CD44 phagocytic efficiency. Under these conditions, there was a 45% decrease in CD44 phagocytic efficiency compared with untreated (control) cells (Figure 2A). Importantly, the binding of the CD44 Ebabs was not affected under these conditions. To confirm the specificity of the antibody and of the iC3b-coated prey, we noted that treatment with the blocking anti-CR3 antibody completely abolished CR3-mediated phagocytosis. In addition, we performed a rosetting assay with PMA-stimulated human neutrophils to confirm that the phagocytic prey were indeed coated with iC3b (Figure 2B). (Note that after PMA stimulation, neutrophils express high levels of CR3, the receptor for iC3b.35 ) While C3dg is a possible byproduct of the iC3b-coating method, C3dg does not bind CR3.36 Thus, the combination of the positive rosetting assay with human neutrophils and inhibition by the blocking CR3 antibody in murine macrophages provides strong evidence that iC3b is the primary species on the surface of the phagocytic prey.

The presence of functional CR3 is important in CD44-mediated phagocytosis. (A) Efficiency of phagocytosis of CD44 Ebabs and iC3b-opsonized erythrocytes by RAW macrophages preincubated with buffer control or blocking CR3 antibody or nonimmune isotype control antibody. * indicates different from the buffer only and nonimmune IgG2b (P < .05). Data are shown as the means plus or minus SE; n = 6. (B) Transmitted light image of human neutrophils binding iC3b-opsonized sheep red blood cells forming a rosette. (C) Efficiency of phagocytosis of CD44 Ebabs and isotype Ebabs by CD44−/−, CD18−/−, CD44−/−/CD18−/− (double-knockout), and wild-type peritoneal macrophages. * indicates different from wild-type peritoneal macrophages (P < .01). Data are shown as the means plus or minus SE; n = 6.

The presence of functional CR3 is important in CD44-mediated phagocytosis. (A) Efficiency of phagocytosis of CD44 Ebabs and iC3b-opsonized erythrocytes by RAW macrophages preincubated with buffer control or blocking CR3 antibody or nonimmune isotype control antibody. * indicates different from the buffer only and nonimmune IgG2b (P < .05). Data are shown as the means plus or minus SE; n = 6. (B) Transmitted light image of human neutrophils binding iC3b-opsonized sheep red blood cells forming a rosette. (C) Efficiency of phagocytosis of CD44 Ebabs and isotype Ebabs by CD44−/−, CD18−/−, CD44−/−/CD18−/− (double-knockout), and wild-type peritoneal macrophages. * indicates different from wild-type peritoneal macrophages (P < .01). Data are shown as the means plus or minus SE; n = 6.

To corroborate the role of CR3 in CD44-mediated phagocytosis using an independent system, we used peritoneal macrophages from CD18-null mice and compared CD44-mediated phagocytosis in wild-type, CD44-null, and CD18/CD44-null macrophages (the absence of CD18 means that there is no functional CR3 on the macrophages). In CD18-null macrophages, CD44-mediated phagocytosis was significantly diminished (phagocytic index of 49.7) compared with wild-type (phagocytic index of 85.9, a 42% decrease; Figure 2C). Phagocytosis was further diminished in CD44−/− and in CD18−/−/CD44−/− (double-knockout) macrophages. Considered together, these data provide strong evidence for the importance of CR3 in CD44-mediated phagocytosis.

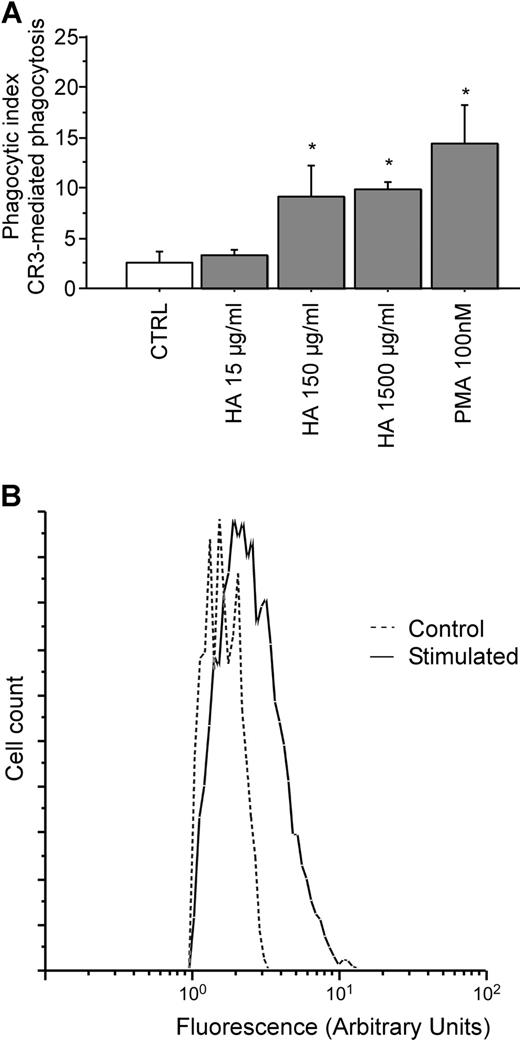

Hyaluronan stimulates CR3-mediated phagocytosis

To study the mechanism of interaction between CD44 and CR3, CD44 was ligated (stimulated) with hyaluronan, and the effects on CR3 activation were compared with the effects of PMA, a known activator of CR3. The extent of activation of the integrin was measured using a CR3-mediated phagocytosis assay. Figure 3A demonstrates that CD44 stimulation by soluble hyaluronan is sufficient to enhance phagocytosis of iC3b-coated prey to a level comparable to that observed after PMA stimulation in RAW macrophages. Hyaluronan stimulation resulted in a phagocytic index of 3.3%, 9.1%, and 9.9%, respectively for increasing concentrations of hyaluronan of 15 μg/mL, 150 μg/mL, and 1.5 mg/mL. By comparison, stimulation of CR3-mediated phagocytosis with 100 nM PMA resulted in a phagocytic index of 14.4%. Finally, exposure of RAW macrophages to hyluronan-coated beads resulted in a 58% increase in CR3 (CD11b) surface expression as assessed by flow cytometry (Figure 3B). These observations support the notion that ligation and activation of CD44 induces activation of CR3.

Pretreatment with soluble hyaluronan increases efficiency of CR3-mediated phagocytosis by RAW macrophages. (A) The efficiency of phagocytosis of iC3b-opsonized erythrocytes by RAW macrophages preincubated with either PMA or hyaluronan at the indicated concentrations for 30 minutes at 37°C is illustrated. * indicates different from the control (P < .05). The data are shown as the means plus or minus SE; n = 6. (B) Fluorescence intensity of RAW macrophages that did not bind or internalize beads (Control; ----) versus macrophages that did bind or internalize hyaluronan-coated beads (Stimulated; —). Data are shown as the logarithmic mean of fluorescent intensity of the Alexa Fluor 488 anti-CD11b antibody. Data are representative of n = 4 independent experiments.

Pretreatment with soluble hyaluronan increases efficiency of CR3-mediated phagocytosis by RAW macrophages. (A) The efficiency of phagocytosis of iC3b-opsonized erythrocytes by RAW macrophages preincubated with either PMA or hyaluronan at the indicated concentrations for 30 minutes at 37°C is illustrated. * indicates different from the control (P < .05). The data are shown as the means plus or minus SE; n = 6. (B) Fluorescence intensity of RAW macrophages that did not bind or internalize beads (Control; ----) versus macrophages that did bind or internalize hyaluronan-coated beads (Stimulated; —). Data are shown as the logarithmic mean of fluorescent intensity of the Alexa Fluor 488 anti-CD11b antibody. Data are representative of n = 4 independent experiments.

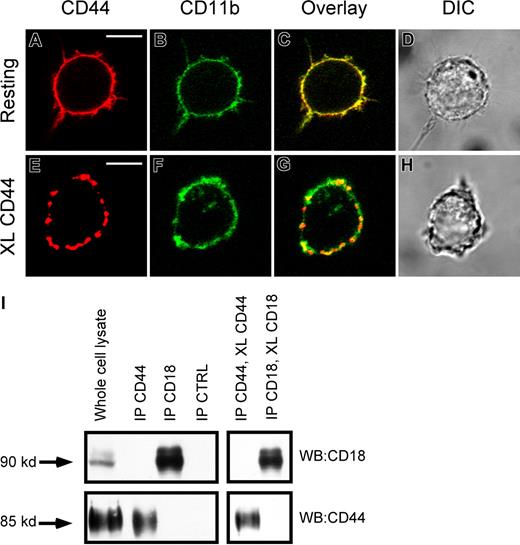

CR3 and CD44 do not physically interact on macrophages

One possible explanation for the involvement of CR3 in CD44-mediated phagocytosis is a physical interaction between these 2 receptors. To investigate this, we used a combination of immunofluorescence microscopy and immunoprecipitation. Immunofluorescence analysis of these receptors on resting cells demonstrated that both receptors were diffusely distributed on the plasma membrane, and that there was a significant amount of overlap (yellow) in their distribution (Figure 4A-D). Cross-linking CD44 with biotinylated antibody followed by avidin cross-linking induced aggregation of CD44 on the cell surface (Figure 4E). In addition, cross-linking CD44 resulted in a degree of spatial colocalization of the aggregated CD44 with CD11b (CR3), providing evidence for physical proximity between these 2 receptors and an increase in the mobility of CR3 (Figure 4C vs 4G). However, using coimmunoprecipitation, we were unable to detect a specific physical interaction between CD44 and CR3 in either the resting state or after antibody cross-linking of CD44 (Figure 4I). We conclude that while there is physical proximity between CD44 and CD18, there is no direct interaction between the 2 receptors under these conditions.

Lack of evidence of physical interaction between CD44 and CR3 (CD11b/CD18). (A,B) Immunofluorescence images of CD44 (red) CD11b (green) of resting RAW macrophages. (C,D) Overlay and direct interference contrast (DIC) images. (E,F) Immunofluorescence of CD44 (red) and CD11b (green) of CD44 cross-linked RAW macrophages. (G,H) Overlay and DIC images. XL indicates cross-linking. Scale bars represent 5 μm. (I) As determined by Western analysis of CD44 and CD18 immunoprecipitates, no detectable binding of the other molecule was observed in the immune complexes. Images are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Lack of evidence of physical interaction between CD44 and CR3 (CD11b/CD18). (A,B) Immunofluorescence images of CD44 (red) CD11b (green) of resting RAW macrophages. (C,D) Overlay and direct interference contrast (DIC) images. (E,F) Immunofluorescence of CD44 (red) and CD11b (green) of CD44 cross-linked RAW macrophages. (G,H) Overlay and DIC images. XL indicates cross-linking. Scale bars represent 5 μm. (I) As determined by Western analysis of CD44 and CD18 immunoprecipitates, no detectable binding of the other molecule was observed in the immune complexes. Images are representative of 3 independent experiments.

CD44 stimulation induces CR3 activation

Lack of physical interaction between CD44 and CR3 led us to consider another possibility that there was “inside-out” activation of CR3 by CD44 stimulation. To investigate this, we examined the recruitment of CR3 to the CD44 phagocytic cup as an indication of increased mobility of the receptor. An increase in lateral mobility of CR3 in the plasma membrane is known to be a key step in signaling of CR3-mediated phagocytosis.37 As shown in Figure 5A, CR3 (CD11b) immunostaining is enhanced at the membrane surrounding the phagocytic prey, consistent with recruitment of CR3 to the phagocytic cup and an increase in mobility of the receptor. To examine this process in more detail, we used fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) analysis to confirm the increase in CR3 mobility. Stimulation of CD44 by cross-linking antibody increased the recovery rate of CR3 after photobleaching compared with control antibody (Figure 5C-R). The time to reach 50% of the original fluorescence intensity (t1/2) is illustrated on the graphs as a solid line. In cells treated with either buffer alone or isotype control, the fluorescence was slow to recover and did not return to 50% of the starting value, even by 350 seconds. In contrast, the t1/2 was reached at 178 seconds and 89 seconds for CD44 and PMA stimulation, respectively, in the experiment illustrated. The t1/2 (recovery time) from 3 independent experiments was more than 350 seconds for untreated control and isotype control antibody, 165 (± 23) seconds for CD44, and 108 (± 15) seconds for PMA. These results support the premise that CD44 signaling increases the mobility of CR3 and thus enhances the efficiency of CD44 phagocytosis.

CR3 (CD11b/CD18) mobility increases after CD44 stimulation. (A,B) Confocal fluorescent and transmitted light images of RAW macrophages stained with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-CD11b prior to CD44-mediated phagocytosis of Ebabs. Arrowheads represent the phagocytic cup. Scale bar represents 5 μm. (C-F) Graphic representation of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of CD11b Alexa Fluor 488 after photobleaching. Cells were untreated (CTRL) or stimulated with antibody (CTRL isotype and CD44) or with 100 nM PMA. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (G-R) Fluorescent images of RAW macrophages stained with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-CD11b before and immediately after photobleaching and then 5 minutes after photobleaching. Scale bar represents 5 μm. The lines labeled 1 or 2 in panels C-F represent the fluorescence intensity over time of the circles in the corresponding fluorescent images (G-R); 1 being the bleached cell and 2 being the control cell.

CR3 (CD11b/CD18) mobility increases after CD44 stimulation. (A,B) Confocal fluorescent and transmitted light images of RAW macrophages stained with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-CD11b prior to CD44-mediated phagocytosis of Ebabs. Arrowheads represent the phagocytic cup. Scale bar represents 5 μm. (C-F) Graphic representation of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of CD11b Alexa Fluor 488 after photobleaching. Cells were untreated (CTRL) or stimulated with antibody (CTRL isotype and CD44) or with 100 nM PMA. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (G-R) Fluorescent images of RAW macrophages stained with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-CD11b before and immediately after photobleaching and then 5 minutes after photobleaching. Scale bar represents 5 μm. The lines labeled 1 or 2 in panels C-F represent the fluorescence intensity over time of the circles in the corresponding fluorescent images (G-R); 1 being the bleached cell and 2 being the control cell.

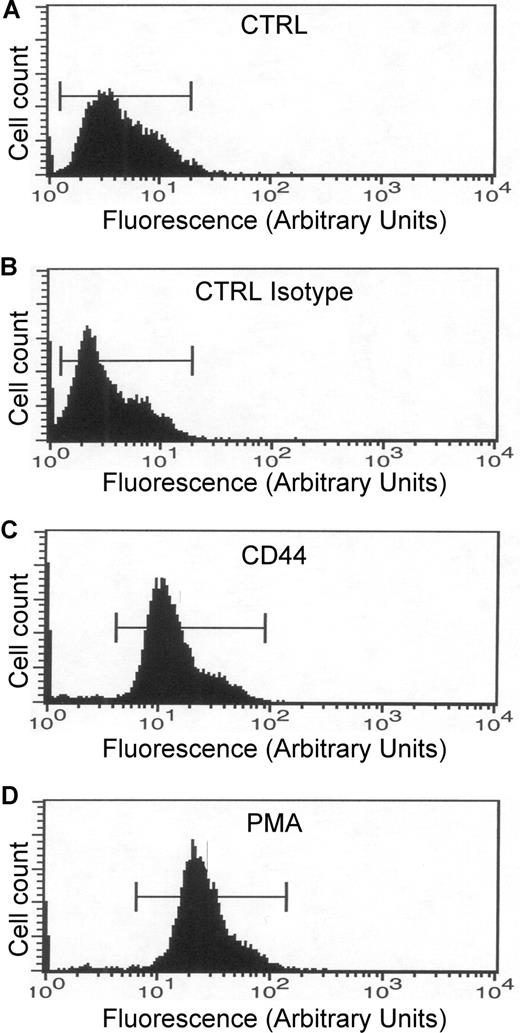

An increase in CR3 affinity for its ligand could also explain the increase in phagocytic efficiency mediated by CD44. To assess the affinity state of CR3, human monocytes were stimulated with CD44 antibody, and the activation state of the receptor was quantified by flow cytometry using a FITC-conjugated antibody that recognizes the high-affinity state of CR3. This analysis revealed that treatment of cells with the anti-CD44 antibody or with PMA increased the state of activation of CR3 dramatically compared with buffer or isotype controls (Figure 6). These results support the hypothesis that activation of CD44 induced inside-out activation of CR3.

CD44 stimulation increases CR3 affinity. (A-D) Flow cytometric analysis of human monocytes. All samples were incubated with the antibody that recognizes the high-affinity state of CR3. (A) CTRL indicates nonstimulated cells. (B) CTRL Isotype indicates cells stimulated with the isotype antibody. (C) CD44 indicates cells stimulated with the CD44 antibody. (D) PMA indicates cells stimulated with 1 μM PMA. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

CD44 stimulation increases CR3 affinity. (A-D) Flow cytometric analysis of human monocytes. All samples were incubated with the antibody that recognizes the high-affinity state of CR3. (A) CTRL indicates nonstimulated cells. (B) CTRL Isotype indicates cells stimulated with the isotype antibody. (C) CD44 indicates cells stimulated with the CD44 antibody. (D) PMA indicates cells stimulated with 1 μM PMA. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

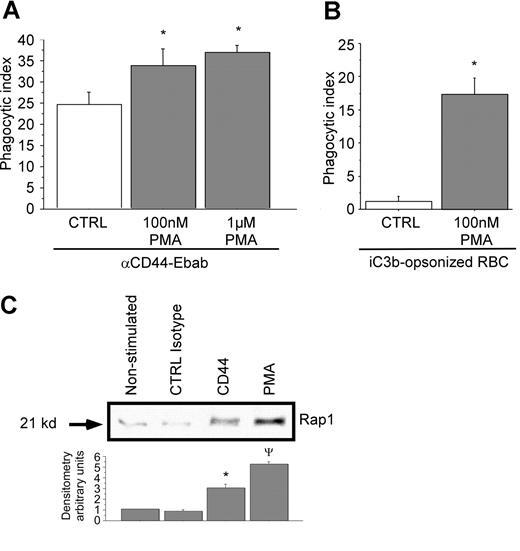

To bolster the concept that CR3 can facilitate CD44-mediated phagocytosis, RAW macrophages were stimulated with the integrin activator PMA. Stimulation with the phorbol ester has been shown to increase integrin mobility and affinity in part by activating the GTPase Rap1.38 In this experiment, pretreatment of RAW macrophages with increasing concentrations of PMA enhanced CD44-mediated phagocytosis (Figure 7A). CR3-mediated phagocytosis with and without PMA was monitored in parallel as an internal control (Figure 7B). These studies demonstrate that the activation state of integrins can modulate CD44-mediated phagocytosis.

Rap1 is activated by cross-linking of CD44 with activating antibody. (A,B) RAW macrophages were treated or not with PMA at the indicated doses prior to phagocytosis of (A) CD44 Ebabs or (B) iC3b-coated prey. * indicates different from the nontreated cells (P < .05). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SE; n = 6. (C) GST-RAL pull-down of activated Rap1 followed by Western analysis of RAW macrophages stimulated or not with PMA, isotype control, or anti-CD44 antibody (representative of 3 independent experiments), followed by densitometry analyses of anti-Rap1 Western blots using Image J 1.47 software. Data are expressed as the ratio of expression of Rap1 relative to nonstimulated control. * indicates different from CTRL isotype and PMA; ψdifferent from CTRL isotype and CD44 (P < .05). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SE; n = 3.

Rap1 is activated by cross-linking of CD44 with activating antibody. (A,B) RAW macrophages were treated or not with PMA at the indicated doses prior to phagocytosis of (A) CD44 Ebabs or (B) iC3b-coated prey. * indicates different from the nontreated cells (P < .05). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SE; n = 6. (C) GST-RAL pull-down of activated Rap1 followed by Western analysis of RAW macrophages stimulated or not with PMA, isotype control, or anti-CD44 antibody (representative of 3 independent experiments), followed by densitometry analyses of anti-Rap1 Western blots using Image J 1.47 software. Data are expressed as the ratio of expression of Rap1 relative to nonstimulated control. * indicates different from CTRL isotype and PMA; ψdifferent from CTRL isotype and CD44 (P < .05). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SE; n = 3.

As mentioned above, the inside-out activation of CR3 by PMA has been shown to involve the GTP-binding protein Rap1.38 This in turn initiates signals that induce internalization of CR3.39,40 To test the possibility that CD44 can activate CR3 through Rap1, we used a Rap1 “pull-down” assay. This assay is based on the capability of the RAL-binding domain to bind activated Rap1 (Rap1-GTP). In this assay, we compared the activating capability of CD44 antibody to an isotype control and to PMA. These studies revealed an increase in Rap1-GTP after CD44 stimulation compared with isotype control antibody or to quiescent cells (Figure 7C). Quantitative (densitometric) analysis revealed that there was a 3-fold increase in activated Rap1 under these conditions. Together, these data strongly support an “inside-out” activation process of CR3 initiated by CD44 stimulation.

Discussion

In this manuscript, we provide evidence that CD44 acts in concert with CR3 to promote CD44-mediated ingestion of particles. In this regard, CD44 is comparable with other pattern-recognition receptors that synergize to function in host defense. For example, the CD11b subunit of CR3 can physically associate with and modulate signals from Fcγ receptors.41,,–44 In addition, a number of other receptors work in concert when they interact with more complex prey such as bacteria that present multiple ligands to the phagocytic cell. For example, CD36 can mediate binding and internalization of Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus via recognition of lipotechoic acid and in addition acts cooperatively with the Toll-like receptors TLR2 and TLR6 to initiate macrophage cytokine production.45 Other examples of cooperative interactions of receptors involved in phagocytosis include the macrophage mannose receptor and DC-SIGN,46 Dectin-1 and TLR2,47 and CD91/calreticulin and signal regulatory inhibitory protein α (SIRPα) in collectin-dependent phagocytosis.48 Indeed, this seems to be a common paradigm that has evolved in cells of the innate immune system and reflects the importance of multiple signals (inputs) into the system with built in redundancy as a “safety net” for these vital processes.

The presence of functional CR3 components (CD11b/CD18) are an important part of CD44-mediated phagocytosis as demonstrated in the experiment with CD18-null mice. Thus, the observed dependence of CD44-mediated phagocytosis on the presence of Mg2+-like cations can be explained by the requirement of activation of CR3 that in turn modulates CD44-mediated phagocytosis. There is precedent for divalent cation involvement in CD44 signaling.49 Vivers et al suggested that CD44 activation had both divalent cation–dependent and –independent components. In their experiments, blockade of CD32 on the apoptotic cells resulted in CD44-mediated phagocytosis becoming divalent cation–dependent. In the current manuscript, we provide a plausible explanation for the divalent cation–dependent pathway—that is, the essential involvement of CR3 as the divalent cation-dependent step. In our studies, we provide strong evidence indicating the importance of either magnesium or manganese in CD44-mediated phagocytosis. The chelation of magnesium by EDTA severely reduces CD44 phagocytosis, while conversely, the addition of magnesium to an HBSS−/− solution rescues the phagocytic properties of CD44 (Figure 1D). Magnesium is an essential cofactor for CR3-mediated events, as it induces signaling and activates the high-affinity state of the receptor.50,51 There is also precedent for activation of integrins via associated or accessory receptors; ligation of Fcγ receptors induces alterations in the affinity state of CD11b and its accumulation in the phagocytic cup, thereby modulating phagocytosis.14 There is also evidence that integrins can modulate phagocytosis in other systems. For example, treatment of cells with an anti- αvβ3 integrin antibody resulted in suppression of phagocytosis of fibronectin.52 In the latter study, the use of an antibody against αvβ3 completely abolished phagocytosis (but not binding) of fibronectin via a mechanism involving α5β1 integrins. The mechanism of this suppressive effect was postulated to involve protein kinase C.

Immunoprecipitation studies of CD44 and CR3 (CD11b) failed to demonstrate a direct interaction between CR3 and CD44, suggesting an indirect mechanism of action. Our studies provide evidence that the mechanism by which CD44 activates CR3 is via an inside-out signaling pathway. Recent studies have firmly established that Rap1 regulates the inside-out activation of integrins.38,39,53,54 Integrin activity is regulated through various mechanisms, including recruitment to the plasma membrane from intracellular stores (change in receptor number), redistribution and clustering at sites of cell adhesion (change in receptor avidity), and conformational changes (change in receptor affinity). Evidence from diverse sources indicates that Rap1 may regulate recycling, avidity, and affinity of integrins that are associated with the actin cytoskeleton.38,39,54,55 Our studies provide evidence that the signaling pathways controlling inside-out activation of CR3 during CD44-mediated phagocytosis involve the GTP-binding protein Rap1. The increase in CR3 mobility induced by CD44 stimulation is most likely attributable to the activation of Rap1. Rap1 is part of the integrin activation pathway involving the focal adhesion kinase family member Pyk2 and other PMA-activated protein kinases.56 In leukocytes, CD44 signaling is mediated by Src family kinases and Pyk2 phosphorylation, leading to cytoskeletal alterations and cell spreading.57 Pyk2 phosphorylation is also induced during phagocytosis of Yersinia by macrophages, a bacteria containing lipopolysaccharide that can mimic some aspects of hyaluronan structure and thus binds CD44.58 β1 integrins (CD29) are known receptors for Yersinia; they promote the removal of the pathogens in macrophages via binding of invasin, a protein expressed on the bacterial cell surface.59,60 The full mechanism is still elusive but appears to involve small GTPases such as Rho, CDC42, and Rac, as well as effectors like WASp and the Arp2/3 complex.60 The presence of the cytosolic domain of the β1 (but not the α) chain was also proven to be critical.61

Interaction of CD44 and β2 integrins during phagocytosis has not been described previously. Other reports describe the interaction of CD44 variant isoforms (but not CD44s) and β1 integrins during binding of osteopontin on cancer cells.28,62 These studies imply an inside-out activation of β1 integrins by CD44 ligation. There is also evidence that antibody binding to CD44 induces the binding of LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18) to intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM) in T cells and in gastrointestinal cancer cells.26,27 In these studies, cross-linking CD44 or addition of a 35-mer hyaluronan fragment induced inside-out activation of integrins via a mechanism involving Src-family kinases. Other pathogenic bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa,63,64 P multocida,65 and group A Streptococcus66 have capsular polysaccharides that contain hyaluronic acid; ligation of CD44 by these bacterially associated ligands may serve as a primary trigger for integrin activation, leading to enhanced bacterial phagocytosis. In contrast, the phagocytic capacity of CD44 in bacterial phagocytosis seems to be variable and depends on the specific microorganism and phagocytic cell type studied. Recently, Rousschop et al investigated the potential of CD44 in urothelial infection mediated by E coli.67 In this study, they observed that the presence of CD44 increased the binding of E coli and facilitated the transmigration of the pathogens into the bladder and kidneys.67

Calcium present in the extracellular environment is tightly controlled by the surrounding cells and systemically in complex organisms by the kidneys and bones. The role of extracellular calcium in phagocytosis is, in general, thought to be relatively minor, although apparent discrepancies exist in the literature.68,69 As 1 example, microglial cell phagocytosis of amyloid-β peptide was diminished in the absence of extracellular calcium (removed by EDTA).68 In another example, the absence of calcium decreased the binding affinity of integrins to human serum albumin–coated plastic, but did not interfere with ingestion of sheep erythrocytes coated with iC3b fragments.69 In the current study, the absence of extracellular calcium actually increased the efficiency of CD44-mediated phagocytosis. This might be explained in part via changes in intracellular calcium because both EDTA and EGTA can also affect intracellular calcium levels over time.70,71 In our experiments using medium that was replenished with Ca2+ and Mg2+ and containing EDTA (Figure 2A), the phagocytic efficiency was lower than in HBSS containing both Ca2+ and Mg2+ but without EDTA. We suspect that the presence of EDTA is responsible for this apparent discrepancy. In this regard, EDTA also chelates Zn2+, Cr2+, Fe2+, and other divalent cations. Indeed, the affinity of EDTA for Zn2+ is much greater than for Ca2+ or Mg2+.72 Importantly, Zn2+ has recently been implicated in the control of inflammation and phagocytosis.73,74

In summary, we have provided strong evidence suggesting that the mechanism of CD44-mediated phagocytosis involves inside-out signals transmitted to CR3 through Rap1. In turn, these signals lead to an increase in the mobility of CR3, possibly via alterations in the actin cytoskeleton, and to an increase in the high-affinity state of CR3 in a magnesium-dependent manner. CR3 is then recruited to the phagocytic cup, where it binds to surface proteins present on the phagocytic prey. Finally, the phagocytic machinery attracted by CD44 and CR3 enacts uptake of the prey. This model does not, however, exclude the possibility that CD44 can function in conjunction with other receptors such as tetraspanins or other low-affinity phagocytic receptors.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation to G.D. and S.G. C.M.D. is supported by an NIH operating grant. G.D. is the recipient of a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair. S.G. holds the Pitblado Chair in Cell Biology from the Hospital for Sick Children.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: E.V. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; R.M. performed research; V.K. performed research; V.C. performed research; C.-W.C. helped design research; C.M.D. contributed vital new reagents and analytical tools; J.P. performed research; S.G. designed research and helped write the paper; and G.P.D. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gregory P. Downey, K701b, Academic Affairs, National Jewish Medical and Research Center, 1400 Jackson St, Denver, CO 80206; e-mail:downeyg@njc.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal