Dyskeratosis congenita (DC) is a multisystem bone marrow failure syndrome characterized by a triad of mucocutaneous abnormalities and an increased predisposition to malignancy. X-linked DC is due to mutations in DKC1, while heterozygous mutations in TERC (telomerase RNA component) and TERT (telomerase reverse transcriptase) have been found in autosomal dominant DC. Many patients with DC remain uncharacterized, particularly families displaying autosomal recessive (AR) inheritance. We have now identified novel homozygous TERT mutations in 2 unrelated consanguineous families, where the index cases presented with classical DC or the more severe variant, Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson (HH) syndrome. These TERT mutations resulted in reduced telomerase activity and extremely short telomeres. As these mutations are homozygous, these patients are predicted to have significantly reduced telomerase activity in vivo. Interestingly, in contrast to patients with heterozygous TERT mutations or hemizygous DKC1 mutations, these 2 homozygous TERT patients were observed to have higher-than-expected TERC levels compared with controls. Collectively, the findings from this study demonstrate that homozygous TERT mutations, resulting in a pure but severe telomerase deficiency, produce a phenotype of classical AR-DC and its severe variant, the HH syndrome.

Introduction

Dyskeratosis congenita (DC) is a genetically and clinically heterogeneous inherited bone marrow (BM) failure syndrome that is classically characterized by a mucocutaneous triad of abnormal skin pigmentation, nail dystrophy, and leukoplakia, as well as a wide range of other cutaneous abnormalities.1 The X-linked recessive form of DC was linked to mutations in DKC1, which encodes the highly conserved multifunctional protein dyskerin.2,,,,–7 Dyskerin associates with a subclass of small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) through the RNAs H/ACA domain.8,–10 These 2 molecules ultimately form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex with the additional proteins GAR1, NHP2, and NOP10.11,–13 This complex has at least 2 significant biologic functions. First, it is responsible for the pseudouridylation of ribosomal RNA at residues specified by the snoRNA contained within the RNP.14 Second, in addition to these pseudouridylation functions, the vertebrate version of this RNP complex associates with a reverse transcriptase (RT) to form the telomerase complex.15,–17

Telomeres are unique tandem repeat structures located at the ends of linear eukaryotic chromosomes.18 Their presence serves many functions including prevention of chromosome end-to-end fusion, maintenance of chromosomal stability, and prevention of chromosomal degradation.19 Telomerase is a specialized RNP complex that elongates the G-rich telomeric repeats.20,21 It is proposed that telomerase acts after DNA replication where this specialized enzyme extends the leading DNA strand, reestablishing the 3′ overhang that is lost during normal cell division due to end processing and the “end replication problem.”22,23 The 2 essential components of this telomerase RT are the RNA component (TERC) that contains the RNA template that the RT (TERT) uses to synthesize 6-bp repeats on the 3′ terminal end of telomeric DNA.24 As the telomerase complex also requires dyskerin, the possibility that mutations in other components of the telomerase complex could cause DC was raised.25 Heterozygous TERC mutations have subsequently been characterized in a subset of patients with autosomal dominant (AD) DC, as well as other related BM failure syndromes, suggesting that disruption of the telomerase complex results in defective hematopoiesis.26,,,,,,,,–35 The deletions and base-pair substitutions that have been identified in TERC have been shown to alter telomerase function via haploinsufficiency of the resulting telomerase complex through either loss of catalytic function or dissociation of the telomerase complex itself. The more recent discovery that heterozygous TERT mutations also result in a disease resembling AD-DC raises the question of whether telomerase catalytic activity is the critical function that is disrupted in these BM failure syndromes.34,36,,–39

During our investigations into telomerase dysfunction in the DC registry (DCR), we have found that a rare subset of DC patients has heterozygous TERT mutations. We note, however, that these mutant alleles are not always fully penetrant and do not always segregate with the disease in an AD fashion.33,37 We have now identified 2 consanguineous families in which novel TERT mutations are segregating and that result in affected homozygous children. In this paper, we describe the clinical features of these 2 families and the functional characterization of these homozygous TERT mutations. The findings from these 2 families demonstrate that homozygous TERT mutations resulting in a “pure” telomerase deficiency can produce a phenotype of classical autosomal recessive (AR) DC and its severe variant, the Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson (HH) syndrome.

Patients, materials, and methods

Screening of patients within the DC Registry

Clinical and genetic information has been collected from 277 DC families worldwide.33 Approval for these studies was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Hammersmith Hospital National Health Service (NHS) Trust and Barts and The London NHS Trust. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. To date, the TERT gene has been screened for mutation in 148 cases of DC in which the genetic basis is unknown, and 23 of these appeared to show an AR pattern of inheritance. The 2 families characterized in this paper have been entered into the DC Registry (DCR) as each index case had clinical features that led to a diagnosis of either DC or HH.33 Mutation screening of the TERT gene was performed by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (dHPLC) as described previously.37 DNA fragments that displayed an abnormal pattern of elution in this analysis were reamplified and subjected to direct sequence analysis by BigDye chain termination cycle sequencing and fragment analysis on the 3700 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) to identify the genetic defect. Mutations identified were confirmed by sequencing the reverse strand.

TERT plasmid constructs and mutagenesis

The pcDNA3.1− wild-type (WT) TERC and pcDNA3.1+ WT TERT plasmids were constructed as previously described.30 Both TERT cDNA mutations were produced using the QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) where 2 complementary overlapping primers were designed to contain the mutation to be induced in the TERT cDNA insert (2431C→T, described by Lingner et al40 : forward gacgtcttcctaTgcttcatgtgcca and reverse tggcacatgaagcAtaggaagacgtc; c2701C→T: forward ggtgaacttgTggaagacagtggtga and reverse tcaccactgtcttccAcaagttcacc; where the mutated base is highlighted in bold italics). For each TERT variant, 125 ng of the appropriate forward and reverse mutagenesis primers was added to 1× reaction buffer, 10 ng WT p3.1+TERT, 2% dNTP mix, 6% QuikSolution mix, and 1.25 units PfuTurbo DNA polymerase. Each reaction was denatured at 95°C for 1 minute, cycled 18 times at 95°C for 50 seconds, 60°C for 50 seconds, and 68°C for 11 minutes, and completed with an extension cycle for 7 minutes at 68°C. Competent DH5α cells were then transformed with the resulting DpnI-treated DNA (to remove the original WT plasmid template) following the manufacturer's instructions. Resulting colonies from each transformation were selected for plasmid DNA extraction (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and the TERT cDNA coding sequence of each construct was verified.

Telomerase reconstitution in transfected WI-38 VA13 cells

Confluent WI-38 VA13 cells (human “fibroblast-like” cells, which can be grown in the laboratory and do not express telomerase) were plated out at 2 × 106/10 cm2 plate in antibiotic-free Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Sigma, St Louis, MO). TERT plasmid titration experiments showed that 50 ng TERT plasmid per transfection was in the middle of the telomere repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) linear range (data not shown). Therefore a total of 50 ng p3.1+TERT plasmid was mixed with 8 μg WT p3.1−TERC plasmid and 8 μg phRL-TK (luciferase internal control; Promega, Madison, WI) and made up to 24 μg total DNA with p3.1− vector backbone in 1.5 mL serum-free DMEM. In some experiments, 25 ng of each mutated p3.1+TERT plasmid was mixed with 25 ng WT p3.1+TERT plasmid. Each plasmid mix was transfected into the telomerase-negative cells using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD) and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 overnight.30 After 24 hours, the medium was changed to DMEM containing 10% FCS and the cells were collected 48 hours after transfection. The cells were split into 1× CHAPS buffer for TRAP analysis, 1× lysis buffer for luciferase analysis, and RTL buffer (Qiagen) for RNA extraction and subsequent cDNA preparation.

TRAP analysis

The TRAP lysates were assayed for protein concentration using a DC protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), normalized to 650 ng/μL, and diluted 1:10, 1:40, and 1:160 using 1× CHAPS buffer prior to TRAP analysis. TRAP lysates were analyzed using the TRAPese telomerase detection kit (Intergen, Burlington, MA) as previously described.30 The resulting TRAP products were separated on 12.5% acrylamide-0.5× TBE gels and exposed to X-ray film. TRAP activities were derived from comparing densitometry reading of a specific TRAP ladder repeat from each serial dilution of mutant samples with those from WT samples of at least 3 separate transfection and subsequent TRAP experiments using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). The luciferase lysates were analyzed to ensure concordant transfection efficiency within each transfection experiment using the Renilla luciferase assay protocol (Promega) as previously described.30

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction on TRAP samples

RNA samples were HhaI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) digested and DNaseI (Promega) treated to remove any contaminating genomic or plasmid DNA. The samples were then reverse transcribed by Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) RT (Invitrogen) into cDNA with random hexamer primers using standard procedures. TERC and ABL mRNA expression was determined using the ABI PRISM 3700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) using primers and probes described elsewhere.41,42 Each quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction was prepared in Taqman Universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) containing 2 μL cDNA with either 300 nM TERC primers and 200 nM TERC probe or 100 nM ABL primers and 300 nM ABL probe. Baselines and thresholds were automatically set by the software and used after manual inspection. Samples were normalized using the ABL data, and each result was expressed as a relative percentage compared with the WT sample. PCR efficiencies for each probe set were derived from standard curves using a dilution series covering a 7-log range starting from one randomly selected undiluted cDNA sample (R2 = 0.9987 and R2 = 0.9996 for ABL and TERC, respectively). We selected ABL as a control gene in these experiments because it is the most widely used and validated for quantitative measurements in peripheral blood samples, being the gene of choice in leukemia minimal residual disease (MRD) studies. A multicenter study has shown that, in contrast to other control genes, the ABL gene transcript was similarly expressed in normal and leukemic samples, reflecting considerably different proliferation states.43 We have also validated the use of the ABL probe to 2 other Taqman probes (GAPDH and HPRT) using our own samples, which gave concordant data to that seen with ABL (data not shown). All reactions were run in duplicate or triplicate.

Telomere length measurement

Telomere length was measured by Southern blot analysis using a subtelomeric probe from chromosome 7 (pTelBam8) as previously described.44 The size of peak signal intensity was determined using Gel Blot Pro software (UVP, Upland, CA). Unaffected siblings and spouses in families in which DKC1, TERC, or TERT mutations have been characterized were used as age-matched healthy controls. A linear regression line was calculated for telomere length against age in these healthy individuals. This value was then used to determine the age-adjusted telomere length of affected individuals by expressing the difference between the observed length and the predicted telomere length from the linear regression line (Δtel) as previously described.45

Telomere lengths have also been measured by quantitative PCR on a 7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using primer pairs and PCR conditions as previously described.46 Briefly, 2 measurements were made in triplicate on each DNA sample, one to determine the telomere repeat copy number (T) and another to determine single copy gene (36B4) copy number (S). A reference DNA sample was serially diluted on each plate so that relative quantities of T and S could be determined from standard curves. T/S ratios were expressed relative to a single DNA, and correspond to the relative telomere lengths of each DNA sample.

Quantitative real-time-PCR on primary material

Total RNA was prepared from whole blood using the QIAamp RNA blood mini kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions including an additional DNase1 treatment step. As described in “Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction in TRAP samples,” the resulting RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA and TERC and ABL mRNA expression was determined. Standard curves were generated for each analysis where ABL expression was used as the endogenous control for each cDNA sample and TERC expression was calculated as a TERC/ABL ratio.47 For each data point, the TERC and ABL quantities were measured in triplicate and the mean values were used to establish the TERC/ABL ratio. The reproducibility of the assay was assessed by comparing the TERC/ABL ratio determined from 2 different dilutions of 15 randomly selected samples. Measurements on these 2 dilutions showed very good correlation (R2 = 0.984). All differences between healthy controls and the mutation groups for the TERC/ABL ratio were compared using the Mann-Whitney test.

Results

Clinical presentation of 2 consanguineous families with novel homozygous TERT mutations

The index case of family A was a 13-year-old Libyan girl from a consanguineous marriage (II:4 in Figure 1). She was underweight and short for her age. Investigations showed that she had a hypocellular BM and thrombocytopenia. Her low platelet count was treated initially with prednisolone. This treatment was changed to oxymetholone (an anabolic steroid) on referral to the United Kingdom as by this time she had trilineage hematopoietic defect producing pancytopenia (Table 1). The combination of cutaneous abnormalities observed by physicians in Libya and BM failure led to the diagnosis of putative constitutional aplastic anemia (CAA). Further clinical investigation in our department established that the index case had café-au-lait spots on her trunk and reticulated pigmentation on the nape of the neck. She was also found to have “bluish discoloration” on the tongue with areas of leukoplakia, thin nails on the hands, but more significant nail dystrophy on the toes (Figure 2). Blood analysis at this time found raised IgG but normal IgA and IgM levels, as well as a reduction in all blood lineages but no blasts (Table 1). Chromosomal breakage analysis was found to be normal, ruling out Fanconi anemia (FA). The presence of mucocutaneous features (reticulate skin pigmentation, nail dystrophy, and leukoplakia) in the index case (Figure 2) together with the trilineage BM failure (Table 1) led to the diagnosis of DC. Clinical investigations on the rest of the family found that, while clinically asymptomatic with normal blood counts (Table 1), her parents and an older sister had some mild abnormalities (highlighted in Figure 1). The death of an older sister was from unknown causes at 6 years of age.

The inheritance of novel homozygous TERT mutations. The index case of each consanguineous family is highlighted by an arrow. Inheritance of a single mutated TERT allele in male and female members is indicated by half black squares or circles. Presence of a wild-type TERT allele in male and female members is indicated by half white squares or circles. Therefore the parents in both families are heterozygous for their respective TERT mutation, while the 2 affected female patients, are homozygous mutant for their respective TERT mutation (a solid black circle), suggesting that both the R811C and R901W TERT mutations segregate in these 2 families in an autosomal recessive manner. Solid gray circles or squares indicate that these samples were not available for screening. Specific clinical symptoms of interest are highlighted underneath the age of each individual.

The inheritance of novel homozygous TERT mutations. The index case of each consanguineous family is highlighted by an arrow. Inheritance of a single mutated TERT allele in male and female members is indicated by half black squares or circles. Presence of a wild-type TERT allele in male and female members is indicated by half white squares or circles. Therefore the parents in both families are heterozygous for their respective TERT mutation, while the 2 affected female patients, are homozygous mutant for their respective TERT mutation (a solid black circle), suggesting that both the R811C and R901W TERT mutations segregate in these 2 families in an autosomal recessive manner. Solid gray circles or squares indicate that these samples were not available for screening. Specific clinical symptoms of interest are highlighted underneath the age of each individual.

Features of families with AR inheritance of homozygous TERT mutations

| . | Position . | Age, y . | Status . | Hb level, g/L . | Wbc count, ×109/L . | Platelet count, ×109/L . | MCV level, fl . | Δtel, kb . | TERC/ABL ratio* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family A:† DC clinical phenotype | |||||||||

| I:1 | Mother | 53 | Het | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| I:2 | Father | 57 | Het | 161 | 6.09 | 149 | 92 | n/a | n/a |

| II:1 | Sister | 28 | Het | 144 | 6.0 | 317 | 86 | n/a | n/a |

| II:4 | Index | 13 | Hom | 84‡ | 3.8 | 19 | 101 | n/a | 7.5 |

| Family B:† HH clinical phenotype | |||||||||

| I:1 | Mother | 31 | Het | 139 | 5.2 | 189 | 93 | −2.2 | 4.1 |

| I:2 | Father | 36 | Het | 154 | 5.8 | 206 | 96 | −2.3 | 3.9 |

| II:1 | Brother | 7 | Normal | 139 | 6.8 | 309 | 88 | +1.2 | 4.7 |

| II:2 | Index | 3 | Hom | 113§ | 3.1 | 21 | 103 | −6.5 | 8.0 |

| . | Position . | Age, y . | Status . | Hb level, g/L . | Wbc count, ×109/L . | Platelet count, ×109/L . | MCV level, fl . | Δtel, kb . | TERC/ABL ratio* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family A:† DC clinical phenotype | |||||||||

| I:1 | Mother | 53 | Het | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| I:2 | Father | 57 | Het | 161 | 6.09 | 149 | 92 | n/a | n/a |

| II:1 | Sister | 28 | Het | 144 | 6.0 | 317 | 86 | n/a | n/a |

| II:4 | Index | 13 | Hom | 84‡ | 3.8 | 19 | 101 | n/a | 7.5 |

| Family B:† HH clinical phenotype | |||||||||

| I:1 | Mother | 31 | Het | 139 | 5.2 | 189 | 93 | −2.2 | 4.1 |

| I:2 | Father | 36 | Het | 154 | 5.8 | 206 | 96 | −2.3 | 3.9 |

| II:1 | Brother | 7 | Normal | 139 | 6.8 | 309 | 88 | +1.2 | 4.7 |

| II:2 | Index | 3 | Hom | 113§ | 3.1 | 21 | 103 | −6.5 | 8.0 |

Hb indicates hemoglobin; Wbc, white blood cell; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; Δtel, observed-expected telomere length; DC, dyskeratosis congenita; HH, Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome; Het, heterozygous; Hom, homozygous; and n/a, not available.

Relative units of quantitative real-time (QRT)-PCR analysis: normal range is 1.1 to 15.5; mean is 4.68; standard deviation is 3.78.

Family A: c2431C→T, pArg811Cys (R811C); Family B: c2701C→T, pArg901Trp (R901W).

On oxymetholone.

After red blood transfusion.

Clinical presentation in family A. Photographs of index case of family A with a homozygous R811C TERT mutation showing (A) reticulate skin pigmentation, (B) leukoplakia of tongue, and (C) nail dystrophy. Significant areas are highlighted by white arrows.

Clinical presentation in family A. Photographs of index case of family A with a homozygous R811C TERT mutation showing (A) reticulate skin pigmentation, (B) leukoplakia of tongue, and (C) nail dystrophy. Significant areas are highlighted by white arrows.

The index case of family B was a 3-year-old girl with an Iranian-Jewish ethnic background who is also from a consanguineous marriage (II:2 in Figure 1). She was found to have cerebellar hypoplasia, early BM failure, and leukoplakia after further investigations to elucidate her failure to thrive. Microcephaly, gastrointestinal abnormalities (dysphagia), learning disabilities, and developmental delay were also noted. FA was ruled out early on and in view of the above combination of abnormalities she was diagnosed to have HH syndrome, the severe variant of DC. Clinical investigation of the rest of the family found that they were clinically asymptomatic with normal blood counts (Table 1). The index case went on to develop progressive trilineage hematopoietic BM failure with a profound thrombocytopenia (Table 1).

Identification of 2 novel homozygous TERT mutations

Since the index cases were female, it was highly improbable that DKC1 would be mutated in these 2 families. Consanguinity in both families suggested an AR-DC inheritance pattern, although AD-DC could not be disregarded, as disease anticipation may support the lack of clinical phenotype in the first generations.48 AD-DC due to TERC mutations was subsequently ruled out when screening analysis found that both index cases had WT TERC genes (data not shown). As the core telomerase complex contains TERT and TERC, and in light of the recent heterozygous TERT mutations identified in DC families,33,35,,,–39 TERT was an obvious candidate disease-associated gene in these families.

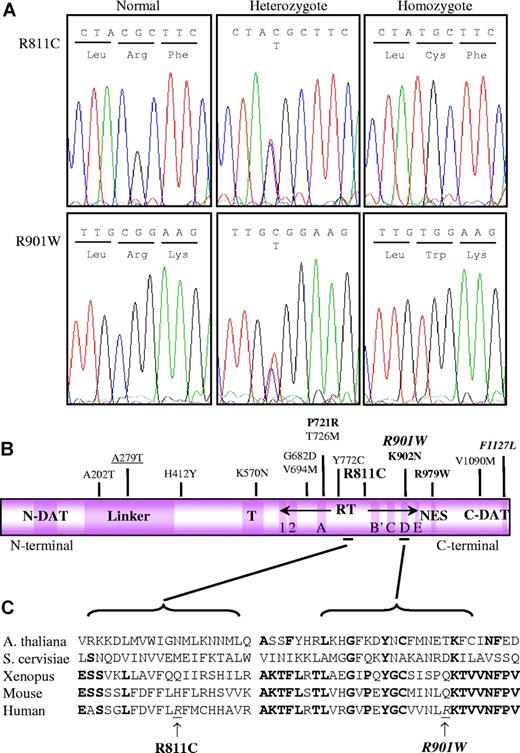

Initial dHPLC screening of the father of family A indicated that he was heterozygous for a mutation in exon 8 of the TERT gene. Subsequent DNA sequence analysis in family A revealed a homozygous c2431C→T nucleotide change in the index case (Figure 3A). This resulted in a pArg811Cys (R811C) substitution in the nonconserved region of the RT domain (Figure 3B). In family B, dHPLC screening of the index case revealed a subtle abnormality in exon 11 of the TERT gene. The index case of family B had a homozygous 2701C→T nucleotide change (Figure 3A) that resulted in a pArg901Trp (R901W) substitution in the conserved D motif of the RT domain (Figure 3B). Neither of these homozygous TERT mutations has been identified as either a homozygous or heterozygous mutation in any of the other 158 subjects of mixed ethnic origin who we have investigated or in any of the other reported TERT screens, including one of 282 control subjects,33,35,,,–39 suggesting these single base-pair substitutions are unlikely to be rare polymorphisms. The segregation of each TERT mutation was confirmed by dHPLC and direct DNA sequence analysis that showed that the parents are heterozygous for their specific mutation and that the presence of the homozygous single base change segregated with the disease phenotype (Figure 1). As the rest of the family members appear asymptomatic in family B, it suggests that the novel R901W TERT mutation induces the clinical phenotype through an AR inheritance pattern.

Genetic characterization of the 2 homozygous TERT mutations. (A) Sequence changes in the TERT gene from both families are shown. Direct DNA sequence analysis shows normal, heterozygous, and homozygous patterns, giving rise to the R811C and R901W substitutions as indicated. (B) A schematic representation of the TERT protein indicates the location of the 2 amino acid substitutions. Conserved domains are indicated by the dark purple boxes, while areas of low conservation are in light purple. Characterized heterozygous mutations and the 2 novel homozygous TERT variants are shown above the linear protein. Their respective clinical phenotypes are indicated as follows: HH in bold italics, DC in bold, AA/MDS in normal text, and polymorphic mutations are underlined. (C) Two regions in the RT domain containing the R811C and R901W substitutions have been expanded below and the amino acid sequence for 5 species aligned. The homozygous mutations (underlined italics) are arrowed. The alignment was carried out by MultAlin.49 The Entrez TERT protein sequences used are as follows: NP_003210 for human, NP_033380 for mouse, AAG43537 for Xenopus laevis, S53396 for Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and T51517 for Arabidopsis thaliana.50 Interestingly, neither amino acid position is highly conserved between the different species. N-DAT/C-DAT indicates N-terminal/C-terminal dissociates activities of telomerase domains; T, telomerase-specific domain; RT, reverse-transcriptase domain; and NES, nuclear export signal domain.

Genetic characterization of the 2 homozygous TERT mutations. (A) Sequence changes in the TERT gene from both families are shown. Direct DNA sequence analysis shows normal, heterozygous, and homozygous patterns, giving rise to the R811C and R901W substitutions as indicated. (B) A schematic representation of the TERT protein indicates the location of the 2 amino acid substitutions. Conserved domains are indicated by the dark purple boxes, while areas of low conservation are in light purple. Characterized heterozygous mutations and the 2 novel homozygous TERT variants are shown above the linear protein. Their respective clinical phenotypes are indicated as follows: HH in bold italics, DC in bold, AA/MDS in normal text, and polymorphic mutations are underlined. (C) Two regions in the RT domain containing the R811C and R901W substitutions have been expanded below and the amino acid sequence for 5 species aligned. The homozygous mutations (underlined italics) are arrowed. The alignment was carried out by MultAlin.49 The Entrez TERT protein sequences used are as follows: NP_003210 for human, NP_033380 for mouse, AAG43537 for Xenopus laevis, S53396 for Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and T51517 for Arabidopsis thaliana.50 Interestingly, neither amino acid position is highly conserved between the different species. N-DAT/C-DAT indicates N-terminal/C-terminal dissociates activities of telomerase domains; T, telomerase-specific domain; RT, reverse-transcriptase domain; and NES, nuclear export signal domain.

Novel TERT amino acid substitutions reduce telomerase activity and telomere lengths

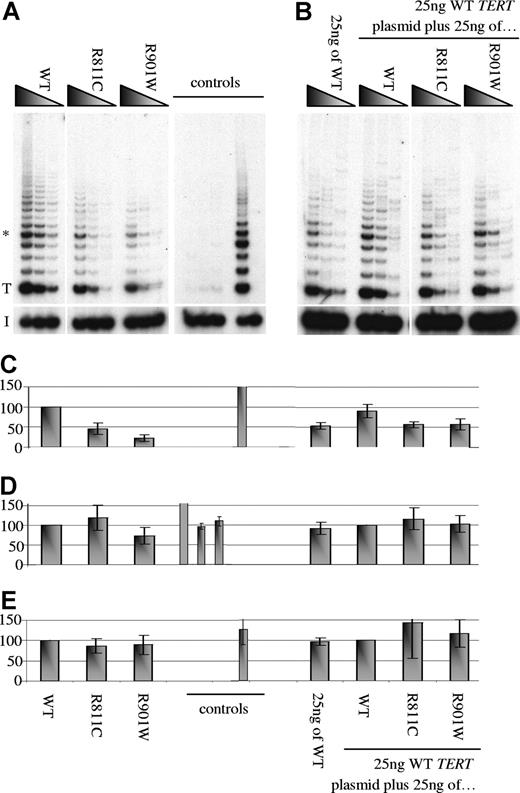

It was not possible to measure telomerase activity in primary cells such as lymphocytes because of lack of appropriate primary material. To determine the consequences of the homozygous amino acid substitutions on telomerase activity, these 2 TERT mutations were transfected into telomerase-negative WI38 cells and the resulting lysates analyzed in reconstituted TRAP assays. The resulting telomerase activity was found to be reduced for R811C (less than 50%) and R901W (less than 25%), respectively, compared with WT controls (Figure 4A). While the index cases were homozygous, their parents were heterozygous for these mutations, yet appeared asymptomatic or mildly suggestive of DC (Figure 1). Since previous reports have suggested that heterozygous TERT mutations can induce disease,33,35,,,–39 we investigated the possibility that these 2 TERT mutations were capable of inducing a dominant-negative effect. When the mutated TERT plasmid was mixed in equal amounts with WT TERT, the resulting telomerase activity was found to be more than 50% of WT activity (Figure 4B). This indicates that the presence of either amino acid substitution was capable of reducing telomerase activity, but there is no inhibition of the WT TERT by the mutated isoform. The in vitro analysis therefore suggests that there is no significant dominant-negative effect of these TERT mutations. However, this assay cannot totally exclude the possibility of any minor dominant-negative effect that might occur in heterozygotes with this mutation in vivo.

Reconstitution of telomerase activity of TERT mutations in vitro. (A) The presence of the TERT amino acid substitutions reduces reconstituted telomerase activity in vitro. (B) There is no evidence of a dominant-negative effect. Serial dilutions of each transfected lysate were assayed as described in “Quantitative real-time-PCR on primary material.” The control panel contains 2 sets of data: the first triplet contains mock transfection, luciferase plasmid alone, and luciferase with WT TERC plasmid lysates, which were expected to yield no telomerase activity but similar luciferase levels; the second half shows HeLa (+) and heat-inactivated HeLa (−) lysates. T and I denote the start of the TRAP ladder and the corresponding internal control, respectively. (C) Densitometry readings using the triplicate band highlighted with * in panel A were analyzed.34 The means and SD from 3 separate transfection and subsequent TRAP experiments are shown. (D) Luciferase levels (expressed as a percentage of counts/μg protein compared with the WT sample) and (E) TERC levels (normalized using ABL and expressed as a relative percentage compared with the WT sample) were concordant among lysates analyzed from 3 separate transfection and TRAP analysis experiments. The amino acid substitutions are shown above the panels and below the graphs.

Reconstitution of telomerase activity of TERT mutations in vitro. (A) The presence of the TERT amino acid substitutions reduces reconstituted telomerase activity in vitro. (B) There is no evidence of a dominant-negative effect. Serial dilutions of each transfected lysate were assayed as described in “Quantitative real-time-PCR on primary material.” The control panel contains 2 sets of data: the first triplet contains mock transfection, luciferase plasmid alone, and luciferase with WT TERC plasmid lysates, which were expected to yield no telomerase activity but similar luciferase levels; the second half shows HeLa (+) and heat-inactivated HeLa (−) lysates. T and I denote the start of the TRAP ladder and the corresponding internal control, respectively. (C) Densitometry readings using the triplicate band highlighted with * in panel A were analyzed.34 The means and SD from 3 separate transfection and subsequent TRAP experiments are shown. (D) Luciferase levels (expressed as a percentage of counts/μg protein compared with the WT sample) and (E) TERC levels (normalized using ABL and expressed as a relative percentage compared with the WT sample) were concordant among lysates analyzed from 3 separate transfection and TRAP analysis experiments. The amino acid substitutions are shown above the panels and below the graphs.

Investigation of telomere lengths (Figure 5; Table 1) shows that the index case from family B has one of the shortest telomere lengths that we have observed in our cohort of patients (DCR). It lies well below the best-fit-line and outside the 95% deviation area of the normal range (black diamond in Figure 5A). The asymptomatic heterozygous R901W parents lie within the 90% deviation area of the normal range (gray diamonds in Figure 5A), and it is therefore possible to speculate that the presence of significantly short telomere lengths in the index case is a result of inheriting shorter-than-expected telomeres from both parents. If this were the case, the homozygous WT brother would also have shorter-than expected telomere lengths. Interestingly, the brother from family B has a telomere length that lies above the best-fit-line but within the 68% deviation from the normal range (white diamond in Figure 5A). To confirm this result, relative telomere lengths were also investigated in family B using a quantitative PCR assay in which a ratio between telomere repeat copy number (T) and single copy gene copy number (S) is determined.46 In a random selection of 26 high-quality DNA samples, we found that T/S ratios obtained from this assay showed significant correlation with the telomere length measured by Southern blot analysis (Figure 5C). We observe that the index case with the R901W mutation has a T/S ratio below the normal range, the heterozygous parents have low-normal T/S ratios, and the unaffected sibling has a relatively high T/S ratio (Figure 5D).

Telomere length analysis in family B. (A) Healthy subjects are indicated by ○. The best-fit-line through this normal range is shown as a black line that corresponds to the equation Y = 17.821 − 0.0407X. Deviation from the best-fit-line has been highlighted as a dark gray box for 68%, a lighter gray box for 90%, and the palest gray box for 95%. The healthy brother is highlighted as a ◇, while the heterozygous R901W parents are ⧫ and the homozygous R901W index case is a ◆. (B) The Δtel values from healthy subjects from panel A (n = 112) are represented on a linear graph and compared with the R901W family (family B). (C) A random selection of subjects (n = 26) was also analyzed using the T/S ratio method45 and plotted to show the relationship to their TRF measurements in panel A. A linear trend line was added for correlation analysis (R2 = 0.6917). (D) Family B was also analyzed using the T/S ratio method and compared with the healthy subjects from panel C.

Telomere length analysis in family B. (A) Healthy subjects are indicated by ○. The best-fit-line through this normal range is shown as a black line that corresponds to the equation Y = 17.821 − 0.0407X. Deviation from the best-fit-line has been highlighted as a dark gray box for 68%, a lighter gray box for 90%, and the palest gray box for 95%. The healthy brother is highlighted as a ◇, while the heterozygous R901W parents are ⧫ and the homozygous R901W index case is a ◆. (B) The Δtel values from healthy subjects from panel A (n = 112) are represented on a linear graph and compared with the R901W family (family B). (C) A random selection of subjects (n = 26) was also analyzed using the T/S ratio method45 and plotted to show the relationship to their TRF measurements in panel A. A linear trend line was added for correlation analysis (R2 = 0.6917). (D) Family B was also analyzed using the T/S ratio method and compared with the healthy subjects from panel C.

Investigations into TERC levels were also carried out. These results show that the amount of TERC is high in both homozygous index cases (Figure 6; Table 1). This is in contrast to DC patients with hemizygous DKC1 mutations, where TERC levels in peripheral blood are significantly reduced compared with healthy individuals (t test: P < .001 compared with controls; Figure 6). Interestingly, patients with heterozygous P721R TERT mutations33 have TERC levels in a similar range to healthy controls (t test: P = .17 compared with controls; Figure 6). Meanwhile, both sets of heterozygous TERT parents and the homozygous healthy brother have TERC levels near the mean value (Figure 6; Table 1). These results demonstrate that while low TERC levels are a consistent feature of X-linked DC, subjects studied with heterozygous TERT mutations have normal TERC levels and, although numbers are small at present, the 2 homozygous TERT patients have raised TERC levels.

TERC levels in peripheral blood samples. The TERC/ABL transcript ratio is shown for a group of healthy individuals (○), P721R and R901W TERT heterozygotes (⧫ and  , respectively), TERT homozygotes (▴ for R811C and ■ for R901W), and patients with DKC1 mutations (•). The family with the heterozygous P721R TERT mutation and those with DKC1 mutations33 are shown for comparison. The numbers of samples in each group is given below along with their corresponding t test value, if appropriate.

, respectively), TERT homozygotes (▴ for R811C and ■ for R901W), and patients with DKC1 mutations (•). The family with the heterozygous P721R TERT mutation and those with DKC1 mutations33 are shown for comparison. The numbers of samples in each group is given below along with their corresponding t test value, if appropriate.

TERC levels in peripheral blood samples. The TERC/ABL transcript ratio is shown for a group of healthy individuals (○), P721R and R901W TERT heterozygotes (⧫ and  , respectively), TERT homozygotes (▴ for R811C and ■ for R901W), and patients with DKC1 mutations (•). The family with the heterozygous P721R TERT mutation and those with DKC1 mutations33 are shown for comparison. The numbers of samples in each group is given below along with their corresponding t test value, if appropriate.

, respectively), TERT homozygotes (▴ for R811C and ■ for R901W), and patients with DKC1 mutations (•). The family with the heterozygous P721R TERT mutation and those with DKC1 mutations33 are shown for comparison. The numbers of samples in each group is given below along with their corresponding t test value, if appropriate.

Discussion

These are the first reports of homozygous amino acid substitutions in TERT. They result in a clinical phenotype of either classical DC or HH, which is a severe variant of DC. They also represent the first genetic characterization of any case of AR-DC/HH. Individuals with heterozygous TERT mutations published to date33,35,,,–39 do not have the features of nail dystrophy and skin pigmentation abnormalities that have been observed in the index cases described here. This study therefore shows that a clinical phenotype close to classical DC can be produced in patients with homozygous mutations in TERT and can be associated with a “pure telomerase defect.” This defect is highlighted by the presence of very short telomeres observed in the index case of family B. The reduced telomerase activity observed in the TRAP assays for both novel mutations suggests that the index cases in both of these 2 families would have less than 50% of normal telomerase activity in vivo.

TERT is a member of a large family of nucleic acid–dependent polymerases with conserved primary sequence motifs. While the tertiary structure of the TERT RT domain is unknown, telomerase-specific areas have been located in both the N- and C- termini peptide regions.51,–53 Key residues in the TERT peptide (Figure 3B), termed the RT motifs, were found to alter RT catalytic function and reduce telomerase activity.54,55 The R811C amino acid substitution is positioned within the RT domain but in a section of low conservation (Figure 3C). The amino acid at position 811 in human TERT has no specific feature linking it to the equivalent amino acid in other species (ie, charge, aromatic ring, etc). The R901W amino acid substitution is also located in the RT domain but it is within the highly conserved D motif (Figure 3C). It lies beside the perfectly conserved K902 amino acid that was found to be mutated in another DC family,36 although the R901 amino acid itself is not highly conserved between the 5 species investigated. Of the 2 mutations that we have identified here, the R901W substitution resulted in a lower telomerase activity and is associated with a more severe clinical phenotype (HH). It is possible that homozygous mutations in highly conserved residues would be lethal as these would be predicted to result in negligible telomerase activity in vivo, and therefore would be incapable of maintaining normal growth and development.

DC is a genetically heterogeneous genetic disorder.56 But regardless of the inheritance pattern, progressive loss of cellular renewal associated with short telomeres has been observed. In cells from patients with X-linked recessive DC, lower TERC levels have been observed along with short telomeres.25,57 Haploinsufficiency of TERC leads to the AD inheritance of DC.26,33 This also appears to be the case with heterozygous inheritance of mutated TERT.33,35,,,–39 In this paper, we demonstrate that homozygous TERT mutations lead to reduced telomerase activity, shorter-than-expected telomeres, and a suggested increase of TERC levels. It has been documented that both X-linked DC and AD-DC may arise due to limitation of TERC levels.57,58 Our study now shows that classical DC can also arise due to severe deficiency of TERT, but that low TERC levels do not appear to be a uniform feature of DC. Indeed the index cases of both families with homozygous TERT mutations were found to have raised TERC levels reflecting possible feedback mechanisms to compensate for the severe TERT deficiency. Therefore it seems that impaired telomerase function through dyskerin, TERC, or TERT defects is sufficient to induce a DC clinical phenotype.

It is noteworthy that some of the heterozygous individuals in these families had subtle features of DC (Figure 1). While the heterozygous R901W parents in family B had relatively short telomeres but were asymptomatic, the parents in family A had mild nail or skin pigmentation abnormalities. As there is a 20-year age difference between these 2 sets of parents, it is possible that the clinical features in family B simply require more time to develop, in a similar manner to the disease anticipation observed in AD-DC TERC families.48 We also note that while the presence of the homozygous R901W TERT mutation led to a significant reduction in telomere length, this shortening appeared to be reversed when the R901W alleles were absent, as the unaffected healthy sibling has relatively long telomeres.

The clinical observations seen in heterozygous individuals of both families are consistent with previous reports of a variable range of presentation in individuals carrying heterozygous TERT mutations.33,35,,,–39 The mild but variable phenotypic expression in part probably reflects the position of the different mutations within the TERT molecule as well as the effect of other environmental and/or genetic factors and therefore the various functional consequences that they might have on TERT activity, stability, or accumulation. The fact that as a group these heterozygotes are usually phenotypically mild compared with the classical presentation of DC, which we see in the homozygous index cases described here, highlights the dosage effect of having 1 versus 2 mutant TERT alleles.

It is unusual, but not unprecedented, for mutations in the same gene to give rise to both dominant and recessive forms of the same disease. The situation we describe here in TERT is partly analogous to β-thalassemia where heterozygous mutations usually produce only mild hematologic abnormalities, but may on occasion give rise to a dominant β-thalassemia.59 In contrast, those individuals with biallelic mutations in the β-globin gene usually present with a severe hematologic phenotype necessitating regular blood transfusion therapy. The situation with mutations to the telomerase complex is complicated, however, by the phenomenon of disease anticipation in which the dominant disease appears to worsen through successive generations. However, it is clear that the heterozygous TERC and TERT families published to date never have a clinical phenotype as severe as seen in X-linked DC and AR-DC, particularly with respect to the cutaneous features. This is in contrast to the cases with the homozygous TERT mutations described here where the phenotype closely mimics that observed in X-linked DC. This therefore highlights that a severe telomerase deficiency alone is capable of producing a classical and severe DC phenotype.

In conclusion, we describe the first clinical and functional characterization of families with homozygous TERT mutations. The findings of this study elucidate the first genetic characterization of AR-DC/HH syndrome and show that a “pure” but severe telomerase deficiency due to constitutional homozygous TERT mutations can produce a classical phenotype of DC.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

Work in this laboratory is supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council.

We thank our colleagues Nahla Abbas, Natalie Killeen, David Stevens, and Kate Sullivan for their technical assistance throughout our research on dyskeratosis congenita. The ABL primers and probes were a kind gift from Dr J. Kaeda of the Minimal Residual Disease laboratory, Hammersmith Hospital, London, United Kingdom. We also thank all the patients and their clinicians for supporting the Dyskeratosis Congenita Registry, which makes it possible to carry out this research.

Wellcome Trust

Authorship

Contribution: A.M. performed plasmid mutagenesis, transfections, TRAP analysis, and Taqman on TRAP samples and was the main author; A.W. performed dHPLC screening and QRT-PCR analysis. H.T. provided the source of one family's clinical data; Y.M. performed QRT-PCR analysis; M.K. and R.B. performed additional experimental preparation and analysis; T.V. performed sequence analysis and telomere length analysis and was the assisting author; I.D. provided the source of one family's clinical data, was the laboratory head, and was the assisting author.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tom Vulliamy, Academic Unit of Paediatrics, Institute of Cell and Molecular Science, Barts and The London, Queen Mary's School of Medicine and Dentistry, The Blizard Building, 4 Newark Street, London, E1 2AT, United Kingdom; e-mail:t.vulliamy@qmul.ac.uk.