Abstract

T cell–dependent B-cell immune responses induce germinal centers that are sites for expansion, diversification, and selection of antigen-specific B cells. During the immune response, antigen-specific B cells are removed in a process that favors the retention of cells with improved affinity for antigen, a cell death process inhibited by excess Bcl-2. In this study, we examined the role of the BH3-only protein Bim, an initiator of apoptosis in the Bcl-2–regulated pathway, in the programmed cell death accompanying an immune response. After immunization, Bim-deficient mice showed persistence of both memory B cells lacking affinity-enhancing mutations in their immunoglobulin genes and antibody-forming cells secreting low-affinity antibodies. This was accompanied by enhanced survival of both cell types in culture. We have identified for the first time the physiologic mechanisms for killing low-affinity antibody-expressing B cells in an immune response and have shown this to be dependent on the BH3-only protein Bim.

Introduction

Humoral immunity to T cell–dependent antigens is characterized by long-lived memory B cells and antibody-forming cells (AFC), with both populations showing evidence of binding antigen with improved affinity as the response progresses. The generation and preferential survival of antigen-specific B cells with enhanced affinity, a phenomenon known as affinity maturation, is critically dependent on the formation of germinal centers (GC), which provide an environment conducive to B-cell proliferation, immunoglobulin (Ig) variable region gene diversification by somatic hypermutation, and the selective survival of clones with enhanced affinity.1 GC B cells may differentiate into memory B cells or AFCs, whereas those cells deprived of survival signals undergo apoptosis.2,3 B cells emigrate from the GC throughout the response in the form of both memory B cells recirculating in the blood and as AFCs, which home preferentially to the bone marrow in what seems to be an affinity-driven process.4,5 Despite spikes in production associated with immune responses, the overall size of the B- cell memory compartment, comprising both memory B cells and long-lived AFCs, remains relatively constant. Thus, newly generated AFCs have to compete with other newly generated and with preexisting AFCs for limited survival-promoting niches.5 Although not as well defined, the size of the memory compartment is also relatively static, suggesting homeostatic regulation.6 The mechanisms underpinning the homeostasis of these B-cell populations are not fully understood.6

Transgenic expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL has been shown to perturb B-cell immune responses.7,8 Upon immunization with the model antigen NP-KLH ([4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl]acetyl-keyhole limpet hemocyanin), bcl-2 transgenic mice accumulate in their spleens abnormally increased numbers of antigen-specific B cells, with particularly striking increases in memory B cells and AFCs that have not sustained affinity-enhancing mutations.9 This indicates that homeostasis of these cell populations is regulated at least in part by the death of B cells expressing low-affinity antigen receptors, which are unable to compete efficiently for survival signals. In the bone marrow, bcl-2 transgenic mice had essentially normal numbers of AFCs and, as in wild-type (wt) mice, most produced high-affinity antibodies.8,9 This observation led to the conclusion that AFCs are selectively recruited to the bone marrow on the basis of antigen receptor affinity and not simply because of increased survival capacity.8

The “Bcl-2-regulated” (also called “mitochondrial” or “intrinsic”) apoptosis pathway is initiated by BH3 (Bcl-2 homology domain 3)-only proteins (Bad, Bim/Bod, Bid, Bik/Blk/Nbk, Hrk/DP5, Noxa, Bmf, and Puma/Bbc3), a proapoptotic subgroup of the Bcl-2 family in which all have a BH3 domain but lack other Bcl-2 homology regions.10 Individual BH3-only proteins differ in their binding to their pro-survival Bcl-2-like relatives,11 but to kill cells, they all require the action of Bax/Bak (the second proapoptotic subgroup of the Bcl-2 family, which have BH1, BH2 and BH3 domains).10 Among the BH3-only proteins, Bim12 has very prominent functions, because, like Puma but unlike other members, it can bind with high affinity to all pro-survival Bcl-2-like proteins.11 Bim is expressed in many tissues, including lymphoid, myeloid, epithelial, and germ cells.13 Gene targeting experiments have shown that Bim is essential for cytokine deprivation-induced apoptosis of many hematopoietic cell types, hematopoietic cell homeostasis and negative selection of autoreactive T and B cells.14-16

Because Bcl-2 overexpression causes abnormally enhanced survival and in vivo accumulation of memory B cells and AFCs, it seems likely that one or several BH3-only proteins are involved in the apoptosis of these cells during shutdown of a humoral immune response. Bim is an outstanding candidate for this function because it plays a critical role in B-cell development and homeostasis14,16 and is expressed in activated B cells and AFCs.13 Therefore, we analyzed a T cell–dependent humoral immune response in bim−/− mice and found that Bim is essential for the developmentally programmed death of memory B cells and AFCs.

Materials and methods

Mice, antigens, and immunization

All mice were bred and maintained at The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research and all animal procedures were approved by the Royal Melbourne Hospital Animal Ethics Committee. The generation and genotyping of bim−/−,14 bim−/−bad−/−,17 bim−/−bid−/−,18 and vav-bcl-2 transgenic19 mice has been described. The bid−/−20 and vav-bcl-2 transgenic mice19 were generated on an inbred C57BL/6 background. The bim−/− and bad−/− mice were originally generated on a mixed C57BL/6 × 129SV background and were back-crossed onto the C57BL/6 background for 10 or more generations before use in the experiments described here. Mice were immunized with a single intraperitoneal injection of NP (100 μg) conjugated to KLH (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) at a ratio of 13:1 and precipitated onto alum.

Immunofluorescent staining, flow cytometric analysis, cell sorting, and IgVH gene sequencing

Spleen, bone marrow and blood were collected and processed as described previously.4 Single cell suspensions or B220+ enriched cell populations (enriched using MACSORT columns [Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany], with B cell purity verified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis to be > 85%) were stained using the following rat monoclonal antibodies: RA3–6B2 (anti-B220), 331.12 (anti-IgM), 11-26C (anti-IgD), IgG1 X56 (anti-IgG1; BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ), MI/70 (anti-Mac-1), RB6-8C5 (anti-Gr-1), 281.2 (anti-CD138; BD Pharmingen), NIMR-5 (anti-CD38), 1D3 (anti-CD19), and F4/80 (anti-macrophage specific antigen). NP binding was detected as described previously.21 Stained cells were analyzed on a FACStar+ or FACSDiva (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Single antigen-specific B cells were sorted and subjected to VH186.2 gene polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and sequencing as described previously.8

Enzyme-linked immunospot assay

To enumerate AFCs, enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays were performed by titrating spleen- or bone marrow-derived leukocytes into NP20- or NP2-bovine serum albumin-coated cellulose ester-based plates and cultured overnight. Bound anti-NP antibodies were visualized by staining with goat anti-mouse IgG1 antibodies directly coupled with horseradish peroxidase (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) as described by Smith et al,22 and spots were counted with an ELISPOT reader system (Autoimmun Diagnostika, Strassberg, Germany).

Cell death assays

To measure memory B-cell survival in vitro, splenic leukocytes were enriched for B220+ cells (MACS Separation Columns, B220 MicroBeads; Miltenyi Biotec); for AFC survival assays, we used single-cell suspensions of spleen or bone marrow. For both assays, cells were counted and cultured at 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C. At the time points indicated in the Figure legends, cells were subjected to ELISPOT analysis or stained for memory B cells then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and analyzed as described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Student t test. P values of .05 or less were considered significant.

Results

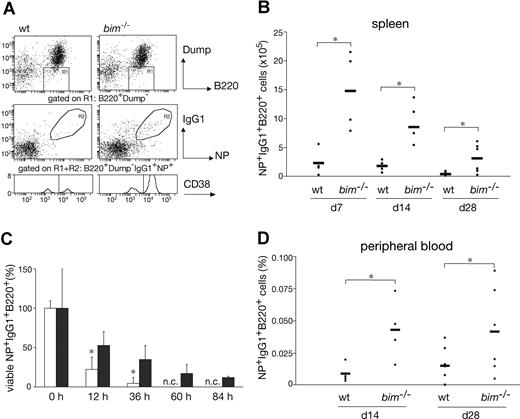

Loss of Bim caused accumulation of antigen-specific B cells due to enhanced survival

To examine the role of Bim in a T-cell–dependent B-cell immune response, bim−/− mice were immunized with NP-KLH and their cellular response monitored after 7, 14, and 28 days. First, we performed immunofluorescent staining with surface marker-specific antibodies and FACS analysis to compare the numbers of NP-specific IgG1+ B cells (IgM−IgD−Gr-1−Mac-1−B220+IgG1+NP+) between wild-type (wt) and bim−/− mice (Figure 1A). In the spleen, we found that, compared with wt controls, bim−/− mice had approximately 3-fold increased percentages and more than 5-fold increased total numbers of IgG1+NP+ B cells at all time points (Figure 1B). Likewise, the percentages of IgG1+NP+ B cells in the peripheral blood were increased by approximately 2- to 3-fold in bim−/− mice (Figure 1D). Because bim−/− mice have approximately 3- to 5-fold higher numbers of blood leukocytes than wt mice (data not shown),14 the total number of antigen-specific B cells in blood is increased by approximately 5- to 10-fold.

Bim-deficiency led to prolonged survival and abnormal accumulation of antigen-specific B cells. Mice (wt and bim−/−) were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg of NP coupled to KLH; 28 days later, leukocytes were collected from the spleen and stained with the indicated antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Viable cells were gated on dump-channel negative (IgM−IgD−Gr-1−Mac-1−) and B220+ cells (R1). Among the cells in R1, those that had switched isotype to IgG1 and possessed the ability to bind the immunizing hapten NP coupled to the fluorescent protein allophycocyanin (APC) result in a population of antigen-specific IgG1+NP+ B cells (R2). These gated cells (R1R2) were then analyzed for CD38 expression to discriminate between memory (CD38high) and GC B cells (CD38low). The total numbers of antigen-specific IgG1+NP+ B cells in the spleen (B) and their percentages in blood (D) were determined as illustrated in (A). Data represent the mean (± SD) of n = 4 to 8 mice; (*P ≤ .05). (C) B220+ enriched B cells from immunized wt (□) and bim−/− (■) mice were cultured for the indicated times in simple medium, harvested, and stained to enumerate antigen-specific IgG1+NP+ B cells as shown in (A). The initial number of viable IgG1+NP+ B cells at time 0 h was set as 100%, and the proportion of viable cells remaining after the different times in culture is displayed (n.c. = no cells). Data represent means (± SD) of n = 3 mice. (*P < .02).

Bim-deficiency led to prolonged survival and abnormal accumulation of antigen-specific B cells. Mice (wt and bim−/−) were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg of NP coupled to KLH; 28 days later, leukocytes were collected from the spleen and stained with the indicated antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Viable cells were gated on dump-channel negative (IgM−IgD−Gr-1−Mac-1−) and B220+ cells (R1). Among the cells in R1, those that had switched isotype to IgG1 and possessed the ability to bind the immunizing hapten NP coupled to the fluorescent protein allophycocyanin (APC) result in a population of antigen-specific IgG1+NP+ B cells (R2). These gated cells (R1R2) were then analyzed for CD38 expression to discriminate between memory (CD38high) and GC B cells (CD38low). The total numbers of antigen-specific IgG1+NP+ B cells in the spleen (B) and their percentages in blood (D) were determined as illustrated in (A). Data represent the mean (± SD) of n = 4 to 8 mice; (*P ≤ .05). (C) B220+ enriched B cells from immunized wt (□) and bim−/− (■) mice were cultured for the indicated times in simple medium, harvested, and stained to enumerate antigen-specific IgG1+NP+ B cells as shown in (A). The initial number of viable IgG1+NP+ B cells at time 0 h was set as 100%, and the proportion of viable cells remaining after the different times in culture is displayed (n.c. = no cells). Data represent means (± SD) of n = 3 mice. (*P < .02).

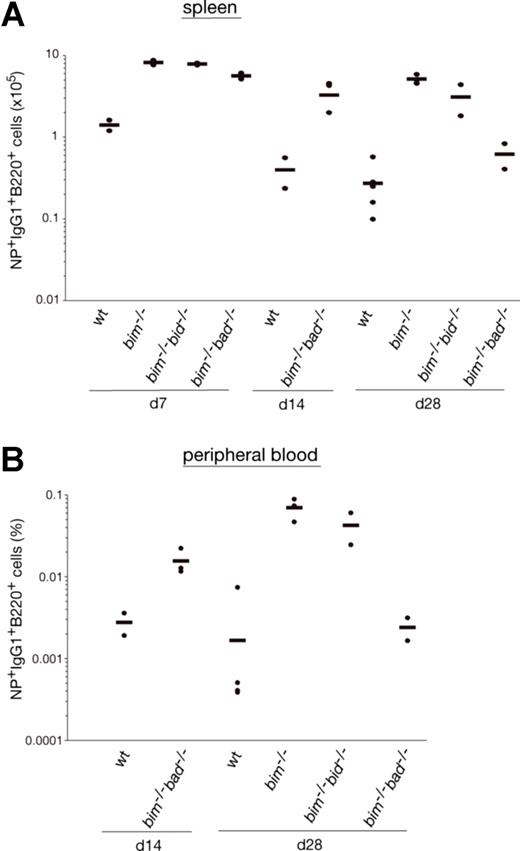

It is widely accepted that apoptosis plays a critical role in the termination of B-cell and T-cell immune responses.23 It therefore seemed likely that loss of Bim caused abnormal accumulation of IgG1+NP+ B cells because it rendered them resistant to the apoptotic stimuli they normally encounter. To address this, we enriched B220+ B cells from the spleen of wt and bim−/− mice at day 14 after NP immunization, cultured them in simple medium (no added cytokines), and measured the survival of the NP-specific IgG1+ B cells (IgM−IgD−Gr-1−Mac-1−B220+IgG1+NP+) by flow cytometric analysis. Antigen-specific B cells from wt mice died very rapidly; only approximately 4% IgG1+NP+ B cells were found alive after 36 hours, and none were found alive after 60 hours of culture. In contrast, bim−/− B cells survived much better; approximately 12% IgG1+NP+ B cells persisted as late as 84 hours (Figure 1C). These results indicate that Bim-dependent apoptosis plays a critical role in the developmentally programmed death of antigen-specific B cells during shutdown of an immune response. Bcl-2 can interact with several proapoptotic BH3-only proteins. Previous studies9 led us to believe that the accumulation of antigen-activated B cells in bcl-2 transgenic mice is greater than that seen in bim−/− mice. This indicates that, in addition to Bim, other proapoptotic factors, most likely other BH3-only proteins, may also contribute to the death of this B-cell population. The BH3-only protein Bad seemed to be a good candidate, because Bad can be activated by cytokine deprivation,24 and mitogen-activated bim−/−bad−/− double-knockout B cells survive better in culture than bim−/− B cell blasts (Priscilla N. Kelly and A.S., manuscript in preparation). However, NP-KLH immunized bim−/−bad−/− and bim−/− mice had comparable numbers of IgG1+NP+ B cells (Figure 2A,B and Figure S2, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Likewise, additional loss of Bid (in bim−/−bid−/− mice) did not exacerbate the defect in B cell deletion seen in bim−/− mice (Figure 2A,B, Figure S2). It therefore seems unlikely that Bid plays a major role in the death of B cells during immune response shutdown. It seems, however, that the combination of loss of Bim and Bad may alter the kinetics of B cell death during the later stages of the immune response and this is currently being investigated.

Bad- or Bid-deficiency did not further enhance the abnormal accumulation of antigen-specific B cells in bim−/− mice. Mice (wt, bim−/−, bim−/−bad−/−, or bim−/−bid−/−) were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg of NP coupled to KLH, and leukocytes were collected from the spleen after 7, 14, and 28 days. Cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated surface marker-specific monoclonal antibodies and gated on IgM−IgD−Gr-1−Mac-1− cells by flow cytometry and analyzed for their proportion of antigen-specific B220+IgG1+NP+ B cells as illustrated in Figure 1A. The total numbers of antigen-specific IgG1+NP+ B cells in the spleen of bim−/−bad−/− and bim−/−bid−/− (A) were determined, and their percentages in the peripheral blood are also shown (B). Each data point represents a mouse: n = 2-3 bim−/−bad−/− mice, n = 2 bim−/−bid−/− mice, n = 3 bim−/−, and n = 3 wt mice.

Bad- or Bid-deficiency did not further enhance the abnormal accumulation of antigen-specific B cells in bim−/− mice. Mice (wt, bim−/−, bim−/−bad−/−, or bim−/−bid−/−) were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg of NP coupled to KLH, and leukocytes were collected from the spleen after 7, 14, and 28 days. Cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated surface marker-specific monoclonal antibodies and gated on IgM−IgD−Gr-1−Mac-1− cells by flow cytometry and analyzed for their proportion of antigen-specific B220+IgG1+NP+ B cells as illustrated in Figure 1A. The total numbers of antigen-specific IgG1+NP+ B cells in the spleen of bim−/−bad−/− and bim−/−bid−/− (A) were determined, and their percentages in the peripheral blood are also shown (B). Each data point represents a mouse: n = 2-3 bim−/−bad−/− mice, n = 2 bim−/−bid−/− mice, n = 3 bim−/−, and n = 3 wt mice.

Bim deficiency inhibited apoptosis of memory B cells in the spleen

It has previously been shown that 4 weeks after immunization with NP-KLH, bcl-2 transgenic mice have an approximately 10- to 20-fold increased memory B cell compartment compared with wt mice.9 Because loss of Bim caused an abnormal accumulation of the total number of antigen-specific B cells in immunized mice (Figure 1), we investigated whether this increase was due to increased GC B cells, memory B cells, or both. We performed FACS analysis to identify antigen-specific B cells (IgM−IgD−Gr-1−Mac-1−B220+IgG1+NP+ as described for Figure 1A) and subdivided them into germinal center B cells and memory B cells according to their levels of CD38 expression.25 Analysis of the spleen revealed that the total numbers of (CD38hi) memory B cells were increased by more than 7-fold in bim−/− mice compared with control mice throughout the experimental period (Figure 3A). Although GC B cells (characterized by low levels of CD38 expression) were proportionally diminished in the bim−/− mice compared with wt mice, their total number was still increased by approximately 4-fold (Figure 3C). This increase also became apparent in histologic examination of the bim−/− spleens, which contained an abnormally high frequency of GC (data not shown). We also determined the proportions of memory and GC-type B cells in the peripheral blood, but, in contrast to the spleen, no significant difference was detected between wt and bim−/− mice; more than 70% of all B cells exhibited a memory phenotype (Figure 3B-D, Figure S1). However, because bim−/− mice have approximately 3- to 5-fold higher numbers of leukocytes than wt mice (data not shown),14 both of these B-cell populations are increased by this factor in the blood of Bim-deficient mice. Taken together, these results show that Bim plays an essential role in regulating the numbers of GC and memory B cells during a humoral immune response.

Bim-deficient mice accumulated abnormally increased numbers of memory B cells. Wild-type and bim−/− mice were immunized with NP. Spleen cells were harvested after 7, 14, and 28 days and analyzed for their content of IgM−IgD−Gr-1−Mac-1−B220+IgG1+NP+ B cells by flow cytometry (as in Figure 1A). Within this cell population, cells with a memory phenotype (CD38high) and GC phenotype (CD38low) were quantified by FACS analysis (as in Figure 1A). The total numbers of memory B cells in the spleen (A; *P < .05), percentages of memory B cells in the blood (B), total numbers of GC B cells in the spleen (C; *P ≤ .05) and the percentages of GC B cells in the blood (D) are indicated. Data represent the mean (± SD) of n = 4 to 8 mice.

Bim-deficient mice accumulated abnormally increased numbers of memory B cells. Wild-type and bim−/− mice were immunized with NP. Spleen cells were harvested after 7, 14, and 28 days and analyzed for their content of IgM−IgD−Gr-1−Mac-1−B220+IgG1+NP+ B cells by flow cytometry (as in Figure 1A). Within this cell population, cells with a memory phenotype (CD38high) and GC phenotype (CD38low) were quantified by FACS analysis (as in Figure 1A). The total numbers of memory B cells in the spleen (A; *P < .05), percentages of memory B cells in the blood (B), total numbers of GC B cells in the spleen (C; *P ≤ .05) and the percentages of GC B cells in the blood (D) are indicated. Data represent the mean (± SD) of n = 4 to 8 mice.

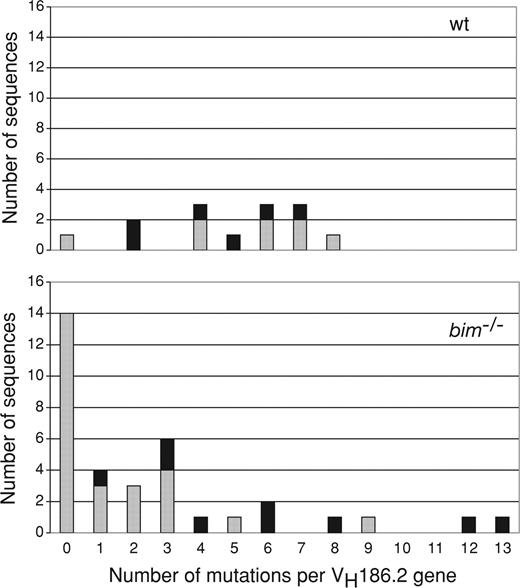

Bim-deficient mice accumulated large numbers of memory B cells with few or no IgVH gene somatic mutations

Bcl-2 overexpression has been shown to affect the process of affinity maturation.8 Because loss of Bim, like Bcl-2 overexpression, inhibits the developmentally programmed death of antigen-activated B cells, we investigated the impact of Bim deficiency on Ig variable gene segment mutation and repertoire selection. GC B cells responding to NP mainly use the VH186.2 gene.26 So we amplified and sequenced rearranged VH186.2-constant region γ1 cDNA from single FACS-sorted splenic B220+NP+IgG1+ cells with a memory phenotype (CD38high) from both wt and bim−/− mice 28 days after immunization. There was a clear difference in both the frequency and distribution of mutations between bim−/− and wt mice (Figure 4). Most strikingly, an unusually large percentage of sequences from bim−/− B cells had zero or one mutation (> 50%) compared with only approximately 7% in wt mice. Accordingly, the average number of mutations per VH186.2 gene was 4.9 in wt B cells but only 2.6 in bim−/− B cells. Moreover, the well-described affinity-enhancing mutation (W33L) in VH186.2 position 33 26 was less frequently detected in bim−/− B cells (25%) than in wt B cells (∼43%) (Table 1). These results show that loss of Bim changes the composition of the memory B-cell compartment but does not prevent somatic hypermutation and production of memory B cells expressing antigen receptors with enhanced affinity. Rather, Bim deficiency causes abnormal preservation of low-affinity antibody-producing memory B cells.

Abnormal persistence of memory B cells with no or only few VH186.2 gene somatic mutations in bim−/− mice. Wild-type and bim−/− mice were immunized with NP-KLH, and after 28 days, single antigen-specific IgG1+NP+ B cells with a memory B cell phenotype (CD38high) were sorted by flow cytometry. The cDNAs of the VH186.2 genes of these cells were amplified by PCR, sequenced, and the frequencies of mutations in wt and bim−/− B cells determined by comparison with the germ-line VH186.2 gene sequence. Distribution of somatic mutations in the VH186.2 genes of wt and bim−/− cells. Column height represents the total number of sequences, and the black portion indicates sequences with mutations giving rise to a tryptophan to leucine exchange at amino acid position 33 (W33L), which is known to lead to enhanced affinity for NP.

Abnormal persistence of memory B cells with no or only few VH186.2 gene somatic mutations in bim−/− mice. Wild-type and bim−/− mice were immunized with NP-KLH, and after 28 days, single antigen-specific IgG1+NP+ B cells with a memory B cell phenotype (CD38high) were sorted by flow cytometry. The cDNAs of the VH186.2 genes of these cells were amplified by PCR, sequenced, and the frequencies of mutations in wt and bim−/− B cells determined by comparison with the germ-line VH186.2 gene sequence. Distribution of somatic mutations in the VH186.2 genes of wt and bim−/− cells. Column height represents the total number of sequences, and the black portion indicates sequences with mutations giving rise to a tryptophan to leucine exchange at amino acid position 33 (W33L), which is known to lead to enhanced affinity for NP.

Summary of VH186.2 sequences from NP-specific IgG+ B cells

| . | wt . | bim−/− . |

|---|---|---|

| Single cell PCR, no. | 24 | 56 |

| Positive PCR, no. | 17 | 41 |

| Positive VH186.2, no. | 14 | 36 |

| Range mutations per VH186.2, no. | 0-8 | 0-13 |

| Sequences with zero mutations, % | 7.1% | 38.9% |

| Average total mutations per VH186.2, no. (SD) | 4.9 (2.3) | 2.6 (3.4) |

| W33L substitution, n/N (%) | 6/14 (42.9%) | 9/36 (25%) |

| CDR1+CDR2, R/S (ratio) | 37/5 (7.4) | 39/5 (7.8) |

| FW1-FW3, R/S (ratio) | 16/10 (1.6) | 33/14 (2.4) |

| . | wt . | bim−/− . |

|---|---|---|

| Single cell PCR, no. | 24 | 56 |

| Positive PCR, no. | 17 | 41 |

| Positive VH186.2, no. | 14 | 36 |

| Range mutations per VH186.2, no. | 0-8 | 0-13 |

| Sequences with zero mutations, % | 7.1% | 38.9% |

| Average total mutations per VH186.2, no. (SD) | 4.9 (2.3) | 2.6 (3.4) |

| W33L substitution, n/N (%) | 6/14 (42.9%) | 9/36 (25%) |

| CDR1+CDR2, R/S (ratio) | 37/5 (7.4) | 39/5 (7.8) |

| FW1-FW3, R/S (ratio) | 16/10 (1.6) | 33/14 (2.4) |

Details of the sequences are summarized comparing wt with bim−/− B-cells.

R/S indicates ratio of replacement to silent mutations in all sequences; CDR, complementary-determining region; FW, framework region.

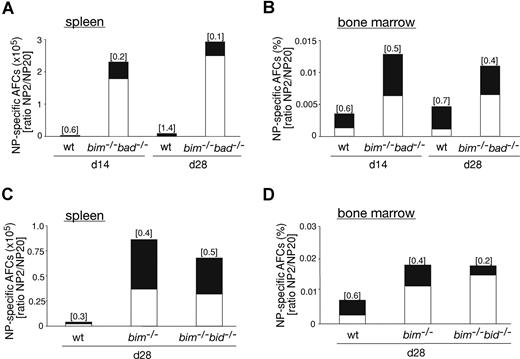

Bim-deficient mice had abnormally elevated numbers of AFCs

Knowing that the GC and memory B-cell compartments are abnormally enlarged in bim−/− mice, we examined whether the AFC population was similarly affected. First, we performed ELISPOT assays to measure the frequency and number of NP-specific IgG1+ AFCs in the spleen and bone marrow of immunized bim−/− and wt animals. The numbers of NP-specific IgG1+ AFCs in the spleen of day 28 immunized bim−/− mice were clearly increased compared with control mice (Figure 5A), particularly given the fact that the input was 106 wt leukocytes and only 105bim−/− leukocytes. Detailed analysis demonstrated that at 14 and 28 days after immunization, bim−/− mice had significantly increased frequencies and total numbers of NP-specific IgG1+ AFCs in both spleen (Figure 5B, top; 13- to 25-fold increase) and bone marrow (Figure 5B, bottom; 2- to 5-fold increase) compared with wt control mice. At day 28, we included bcl-2 transgenic mice in our analysis; remarkably, these animals had even more (∼3-fold) NP-specific IgG1+ AFCs compared with bim−/− mice. We next determined the affinity of the anti-NP antibodies produced using the differential binding to low haptenated (NP2) or high haptenated (NP20) carrier protein to measure the ratio of high-affinity to total (high plus low affinity) anti-NP antibody producing IgG1+ AFCs. This is an established method for analyzing the affinity maturation of the immune response.27 After 14 and 28 days of immunization, spleens of bim−/− mice contained many more (> 10- to 30-fold) AFCs producing low-affinity antibodies compared with wt mice (Figure 5B, top). In contrast, the bone marrow of wt and bim−/− mice had similar frequencies of high-affinity (∼60%-70%) anti-NP AFCs (Figure 5B, bottom). These findings in bim−/− mice are remarkably similar to those previously reported for bcl-2 transgenic mice (see also Figure 5B).8,9 Therefore, loss of Bim results primarily in the abnormal accumulation of low-affinity AFCs in the spleen, but recruitment to the bone marrow still seems to require an affinity-dependent signal. To determine whether this abnormal accumulation of AFCs was associated with abnormally enhanced resistance to apoptosis, we cultured spleen cells from day 14 immunized wt and bim−/− mice in simple medium (no added cytokines) and measured AFC survival by ELISPOT assays. Wt AFCs died very rapidly with only approximately 8% IgG1+NP+ AFCs found alive after 24 hours and approximately 2% after 60 hours of culture. In contrast, bim−/− AFCs survived much better, with approximately 55% IgG1+NP+ B cell alive after 24 hours and approximately 33% as late as 60 hours of culture (Figure 5C). These results indicate that Bim-dependent apoptosis is required for the normal developmentally programmed death of AFCs in the spleen, particularly those AFCs secreting low-affinity antibodies. Given the significantly increased numbers of AFCs in bcl-2 transgenic mice compared with bim−/− mice, it seems likely that other proapoptotic BH3-only proteins also contribute to the death of AFCs. We tested whether Bad or Bid might play a role in this process, but after immunization, bim−/−bad−/− and bim−/−bid−/− mice had numbers of AFCs similar to those of bim−/− mice (Figure 6), although some delay in affinity maturation was evident at day 14 in bim−/−bad−/− mice. This indicates that Bim and Bid probably were not critical for the difference in the programmed death of AFCs that is evident between vav-bcl-2 transgenic and bim−/− mice.

Bim-deficient mice accumulated abnormal numbers of AFCs but still only recruited high-affinity AFCs into the bone marrow. Wild-type and bim−/− mice were immunized with NP-KLH. After 14 or 28 days, spleen and bone marrow were harvested and ELISPOT assays performed to determine the numbers of NP-specific AFCs. (A) The picture shows the total of all IgG1+ NP-specific AFCs (high and low affinity; ie, antibodies capable of binding to NP20) and the high-affinity (ie, antibodies capable of binding to NP2 but not NP20) IgG1+ NP-specific AFCs from the spleen (note: wt input, 106 cells; bim−/− input, 105 cells). (B) Frequencies of NP-specific IgG1+-secreting AFCs in the spleen (left, total cell number) and bone marrow (right, percentage) of wt, bim−/−, and bcl-2 transgenic mice. The total column represents all AFCs (high plus low affinity; ie, binding to NP20) and the high-affinity (antibodies binding to NP2) AFCs are represented by the black proportion of the column. Affinity maturation is calculated as the ratio of NP2/NP20 cells and this is shown on top of each column. Data represent the mean of n = 3 to 9 mice; *P ≤ .008 (spleen) and P ≤ .04 (bone marrow) for both high-affinity and low-affinity anti-NP AFCs. (C) Splenic B cells from NP-KLH immunized wt (white columns) and bim−/− (black columns) mice were cultured in simple medium (no added cytokines) for the indicated times, and ELISPOT assays were performed to enumerate the surviving NP-specific (high-affinity; ie, binding to NP2) AFCs. The number of NP-specific IgG1+ AFCs at time 0 h was set as 100%, and the proportion surviving after the different times in culture is displayed. Data represent mean (± SD) from 4 cultures of 2 mice of each genotype. *P ≤ .02.

Bim-deficient mice accumulated abnormal numbers of AFCs but still only recruited high-affinity AFCs into the bone marrow. Wild-type and bim−/− mice were immunized with NP-KLH. After 14 or 28 days, spleen and bone marrow were harvested and ELISPOT assays performed to determine the numbers of NP-specific AFCs. (A) The picture shows the total of all IgG1+ NP-specific AFCs (high and low affinity; ie, antibodies capable of binding to NP20) and the high-affinity (ie, antibodies capable of binding to NP2 but not NP20) IgG1+ NP-specific AFCs from the spleen (note: wt input, 106 cells; bim−/− input, 105 cells). (B) Frequencies of NP-specific IgG1+-secreting AFCs in the spleen (left, total cell number) and bone marrow (right, percentage) of wt, bim−/−, and bcl-2 transgenic mice. The total column represents all AFCs (high plus low affinity; ie, binding to NP20) and the high-affinity (antibodies binding to NP2) AFCs are represented by the black proportion of the column. Affinity maturation is calculated as the ratio of NP2/NP20 cells and this is shown on top of each column. Data represent the mean of n = 3 to 9 mice; *P ≤ .008 (spleen) and P ≤ .04 (bone marrow) for both high-affinity and low-affinity anti-NP AFCs. (C) Splenic B cells from NP-KLH immunized wt (white columns) and bim−/− (black columns) mice were cultured in simple medium (no added cytokines) for the indicated times, and ELISPOT assays were performed to enumerate the surviving NP-specific (high-affinity; ie, binding to NP2) AFCs. The number of NP-specific IgG1+ AFCs at time 0 h was set as 100%, and the proportion surviving after the different times in culture is displayed. Data represent mean (± SD) from 4 cultures of 2 mice of each genotype. *P ≤ .02.

Additional loss of Bad or Bid did not further increase the abnormally elevated number of high-affinity AFCs and low-affinity AFCs in Bim-deficient mice. Wt, bim−/−, bim−/−bad−/−, or bim−/−bid−/− mice were immunized with NP coupled to KLH. After 14 or 28 days, spleen and bone marrow were harvested, and ELISPOT assays were performed to determine the numbers of NP-specific AFCs. Frequencies of NP-specific IgG1+-secreting AFCs in the spleen of wt and bim−/−bad−/− mice (A, total cell number) or wt, bim−/− and bim−/−bid−/− mice (C, total cell number) and in the bone marrow (B and D, percentage) were determined. The total numbers of AFCs are represented by the overall height of the column (high- plus low-affinity NP-specific AFCs; ie, binding to NP20) and the high-affinity (antibodies binding to NP2) AFCs are represented by the black proportion of the column. The ratio of NP2/NP20 antibody producing cells indicates the affinity maturation, and this is shown on top of each column. Data represent the mean of n = 2-3 bim−/−bad−/− mice, n = 2 bim−/−bid−/− mice, bim−/− = 3 mice, and n = 3 wt mice.

Additional loss of Bad or Bid did not further increase the abnormally elevated number of high-affinity AFCs and low-affinity AFCs in Bim-deficient mice. Wt, bim−/−, bim−/−bad−/−, or bim−/−bid−/− mice were immunized with NP coupled to KLH. After 14 or 28 days, spleen and bone marrow were harvested, and ELISPOT assays were performed to determine the numbers of NP-specific AFCs. Frequencies of NP-specific IgG1+-secreting AFCs in the spleen of wt and bim−/−bad−/− mice (A, total cell number) or wt, bim−/− and bim−/−bid−/− mice (C, total cell number) and in the bone marrow (B and D, percentage) were determined. The total numbers of AFCs are represented by the overall height of the column (high- plus low-affinity NP-specific AFCs; ie, binding to NP20) and the high-affinity (antibodies binding to NP2) AFCs are represented by the black proportion of the column. The ratio of NP2/NP20 antibody producing cells indicates the affinity maturation, and this is shown on top of each column. Data represent the mean of n = 2-3 bim−/−bad−/− mice, n = 2 bim−/−bid−/− mice, bim−/− = 3 mice, and n = 3 wt mice.

Discussion

Apoptotic cell death of antigen-specific lymphocytes plays a critical role in the shutdown of T- as well as B-cell immune responses.28 In this study, we have identified for the first time the physiologic trigger of the apoptotic pathway that regulates the contraction of the antigen-specific B-cell compartment after a T-cell–dependent humoral immune response. Removal of Bim, a proapoptotic BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 protein family, resulted in abnormal accumulation of low-affinity Ig-expressing memory B cells. This highlights the contribution of the apoptotic pathways that are dependent on Bim in the normal selective processes of the GC that generate an appropriately affinity-matured memory B cell population. Bim-deficiency did change the fractions of the memory B-cell population in the spleen and peripheral blood quantitatively but did not prevent somatic hypermutation and the generation of memory B cells, which express antigen receptors with enhanced affinity for the immunogen. Most prominently, loss of Bim led to an abnormal accumulation of low-affinity memory B cells. Thus, Bim seems to be particularly critical for the removal of low-affinity antibody-bearing memory B cells and therefore seems to be necessary for the formation of a normally selected memory B-cell repertoire. The process of affinity maturation still took place within its physiologic location, and the expanded antigen-specific B-cell populations in the blood and spleens of bim−/− mice showed a normal phenotype. This argues against Bim-deficiency permitting the export or accumulation of an abnormal cell type.

Similarly to the removal of memory B cells, the death of low-affinity AFCs in the spleen was also dependent on apoptotic pathways triggered by Bim, and it seems to be particularly critical for the removal of low-affinity antibody-bearing memory B cells. This presumably reflects the apoptotic pathways triggered in these cells by the deprivation of external survival factors.28 It is noteworthy that Bim-deficiency led to an elevated number of low-affinity AFCs in the spleen, but loss of Bim did not affect AFC recruitment to the bone marrow and had no effect on the qualitative composition of the bone marrow AFCs, highlighting the requirements beyond survival for entry into this compartment.8

Previous studies9 led us to believe that bcl-2 transgenic mice have even more antigen-specific B cells (memory B cells as well as AFCs) than bim−/− mice, prompting the hypothesis that other proapoptotic factors, most likely other BH3-only proteins, also play a role in the developmentally programmed death of these cells. The BH3-only protein Bad is known to be activated after cytokine deprivation,24 but bim−/−bad−/− mice, during the early phase of the immune response, had similarly increased numbers of antigen-specific cells compared with bim−/− mice. Bid did not contribute to the death of antigen-specific cells either, as reflected by the observation that bim−/−bid−/− and bim−/− mice had similar numbers of antigen-specific B cells and AFCs. So, which BH3-only proteins might collaborate with Bim in this process? Bik is a possible candidate, because it is induced by antigen receptor cross-linking in B cells,29 but we found no apoptosis defect in bik−/− B cells,30 and bim−/−bik−/− B cells were found to behave similarly to bim−/− B cells both in vitro and in vivo.31 Mice deficient for the BH3-only proteins Noxa,32,33 or Hrk,34 do not exhibit any obvious defects in their immune systems, although no studies on immune responses have so far been reported. Puma may be the best candidate because its loss has been shown to protect B cells and other hemopoietic cell types from apoptosis induced by cytokine deprivation,33,35 and bim−/−puma−/− B cells were found to be as resistant to a range of apoptotic stimuli as bcl-2 transgenic B cells.36 Furthermore, unimmunized bim−/−puma−/− mice have similar concentrations of serum Ig as bcl-2 transgenic animals, which are significantly higher than those found in bim−/− mice.36

Cytokines like BAFF are known to regulate B cell survival by down-regulating Bim via the ERK signaling pathway.37 As demonstrated, the loss of Bim leads to an increased survival of memory B cells and AFCs cultured in the absence of cytokines, such as BAFF or other survival factors. Although it is still not entirely clear which cytokines and other regulatory factors control the survival of antigen-activated B cells and AFCs under physiologic conditions, it seems likely that the death of these cells in vivo during shutdown of an immune response is triggered by a decrease in the levels of such factors, causing the activation of Bim and certain other proapoptotic proteins.

Although we used bim−/− mice to demonstrate that apoptosis of low-affinity germinal center B cells is necessary for the formation of a physiologically selected memory B-cell population, the mechanism of affinity maturation is still controversial. B lymphocytes lacking Bim have been shown to be refractory to apoptosis induced by B-cell receptor ligation in vitro.16 Therefore, the reduction in B-cell receptor stimulation-induced apoptosis of B cells (particularly those with high-affinity BCR) might explain why loss of Bim causes an accumulation of antigen-specific B cells. However, this hypothesis would predict the accumulation of abnormally large numbers of high-affinity B cells and provides no explanation for the dramatic increase of low-affinity B cells found in bim−/− mice. We therefore prefer the model that B cells with low-affinity BCR fail to access niches within germinal centres that produce survival-promoting cytokines and die as a consequence of growth factor deprivation. Because this death is Bim-dependent,14 this would explain the accumulation of low-affinity B cells and AFCs in bim−/− mice.

Finally, this study shows that Bim is critical for apoptosis of germinal center-derived memory B cells and AFCs. Although these results are broadly similar to those obtained with bcl-2 transgenic mice, they are due to the removal of one specific initiator of apoptosis, rather than to overexpression of a global apoptosis inhibitor. As such, they define the physiologically relevant pathway that regulates the homeostasis of antigen-specific B cells during an immune response.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs S. Cory, J.M. Adams, M. Bath, P.N. Kelly, T. Kaufmann, V.M. Dixit, N. Danial, and A. Ranger for gifts of gene targeted and transgenic mice; K. Vella, G. Siciliano, A. Naughton, K. Pioch, N. Iannarella, and J. Allen for expert animal care; B. Helbert and M. Robati for genotyping; Dr F. Battye, V. Milovac, C. Tarlinton, C. Young, and J. Garbe for cell sorting; and Dr S. Mihajlovic, E. Tsui and A. Hasanein for histology.

This work was supported by fellowships and grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to S.F.F.), the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia; programs 257502 and 356202), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (New York; Specialized Center for Research (SCOR) grant 7015), and the National Cancer Institute (National Institutes of Health grants CA80188 and CA43540).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: S.F.F. planned and performed most of the experiments and wrote the manuscript. P.B. contributed essential reagents and ideas and helped with experiments. K.O. and A.L. helped with several experiments. D.T. and A.S. conceived the experimental plan, helped plan experiments, and wrote the manuscript. D.M.T. and A.S. share senior authorship.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dr Andreas Strasser or Dr David M Tarlinton, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, 1G Royal Parade, Parkville, VIC 3050, Australia; e-mail: strasser@wehi.edu.au or tarlinton@wehi.edu.au

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal