The Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) was developed to predict prognosis of patients with follicular lymphoma (FL). However, it was based on different protocols, none of which included rituximab. The current analysis aimed at evaluating the predictive value of the FLIPI for treatment outcome in 362 patients with advanced-stage FL treated front-line with rituximab/CHOP in a prospective trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group. According to the FLIPI, 14% of the patients were classified as low-risk, 41% as intermediate-risk, and 45% as high-risk patients. With a 2-year time to treatment failure (TTF) of 67%, high-risk patients had a significantly shorter TTF as compared with low- or intermediate-risk patients (2-year TTF of 92% and 90%, respectively; P < .001). Our data demonstrate that the FLIPI is able to identify high-risk patients with advanced-stage FL after first-line treatment with rituximab/chemotherapy.

Introduction

The introduction of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab into the treatment of advanced-stage follicular lymphoma (FL) has markedly changed the approach to patients with this disease.1 Despite the overall improvement in treatment outcome by combining rituximab with chemotherapy, response to treatment varies substantially among individual patients.2-4 Thus, treatment recommendations are still difficult and may range from a watch-and-wait strategy to single-agent rituximab or different rituximab chemotherapy combinations up to intensive multimodal concepts including myeloablative therapy followed by autologous stem cell reinfusion.5,6 An important tool for the pretherapeutic assessment of prognosis and the adaptation of treatment strategies in distinct groups of patients has been introduced by the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI). Based on 5 easily evaluable clinical and laboratory parameters (age, Ann Arbor stage, number of nodal areas, LDH, and hemoglobin level) the FLIPI discriminates between 3 major subgroups of patients with FL with regard to overall survival, carrying a low (0-1 risk factors), intermediate (2 risk factors), or high risk (3-5 risk factors).7 The FLIPI was derived from the analysis of patients with FL who were treated in different, mostly multicenter study group protocols. At the time of its assessment rituximab was not established in the first-line treatment of FL and in fact none of the respective regimens contained this agent. Since rituximab has recently been shown to improve the efficacy of antilymphoma chemotherapy substantially when added to various regimens,2,8,9 the combination of rituximab and chemotherapy (R-chemo) has become a widely accepted approach for the first-line therapy of advanced-stage FL.

In order to evaluate the predictive value of the FLIPI in terms of treatment outcome under the conditions of an R-chemotherapy combination, we analyzed a patient cohort of the prospective trial by the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) comparing front-line immunochemotherapy R-CHOP with CHOP.8

Study design

Data collection

The GLSG trial included previously untreated patients age 18 years and older with advanced-stage follicular, mantle cell, or lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma as previously reported.8 Clinical entry criteria were described previously and comprised the need for therapy and Ann Arbor stage III or IV.8 After the trial had shown the superiority of R-CHOP, recruitment was still continued and all patients were assigned to R-CHOP induction. The current analysis included all the registered patients with FL who had received at least one cycle of therapy and were staged at least once for treatment outcome. The trial was approved by the responsible local ethics committees and all patients gave written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Evaluation of treatment outcome

Initial cytoreduction with 4 to 6 cycles of CHOP or R-CHOP was performed as previously described.8 Patients achieving a complete (CR) or partial remission (PR) after induction were offered either consolidating myeloablative therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation or long-term interferon alpha (IFNα) maintenance.10 Response to therapy was evaluated according to the International Working Group Criteria11 after every 2 cycles of induction therapy and 4 weeks after the completion of the last course. Follow-up evaluations were performed every 3 months except for CT scans of previously involved areas, which were repeated every 6 months.

Time to treatment failure (TTF), the main trial efficacy end point, was defined as the interval between the start of treatment and the documentation of stable disease after completion of initial therapy, progressive disease, or death from any cause. Response duration (RD) was calculated from the end of successful (CR or PR) induction therapy to progression or death from any cause. Overall survival (OS) was the time between recruitment and death from any cause.

Statistical analysis

The predictive value of the FLIPI was evaluated in terms of the TTF, which was the primary efficacy parameter of the trial. Secondary parameters were the rate of CR or PR (overall response rate), the RD, and the OS. TTF, overall response rate, RD, and OS were analyzed according to the 3 FLIPI risk groups. If the 3-group comparison showed a significant effect, 2-group comparisons were done on the same significance level according to the closed testing procedure.12 An explorative regrouping of patients according to the number of risk factors aimed at achieving a better discrimination between the risk groups. A multivariate analysis was performed to determine the impact of the FLIPI risk factors (excluding stage, which was III or IV in all patients). The time-to-event variables were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and comparisons of risk groups were done by means of the log-rank test. Two-year event-free survival probabilities were reported, as this value was close to the median follow-up time. Cox regression was performed to calculate hazard ratios as well as 95% confidence intervals (CI), and for the multivariate analysis. Response rates were compared by Fisher exact test. The significance level was 5% for all statistical procedures. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results and discussion

Patients

Between May 4, 2000, and March 1, 2005, 780 patients with advanced-stage FL were included in the trial. From a total of 415 patients treated with R-CHOP, 362 were evaluable for the target parameter TTF, including 75 patients assigned to R-CHOP after the end of randomization in August 2003. Of the 338 patients who were evaluable for the FLIPI, 14% had a low-risk (LR), 41% an intermediate-risk (IR), and 45% a high-risk (HR) score (Table 1). In addition, 268 patients treated with CHOP were evaluable for TTF, and 260 patients for the distribution to FLIPI risk groups, which was similar to the R-CHOP group (12% in LR, 44% in IR, and 45% in HR).

Baseline characteristics of patients analyzed for TTF

Parameter . | R-CHOP,*no. (%) . | CHOP, no. (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 362 | 268 |

| Age, y, median (range) | 56 (24-90) | 57 (21-81) |

| Age 60 years or older | 137 (38) | 103 (38) |

| Male sex | 155 (43) | 141 (53) |

| Stage IV | 248 (70) | 181 (68) |

| B-symptoms present | 143 (40) | 111 (42) |

| LDH > UNL | 104 (29) | 64 (24) |

| Hb < 12 g/dL | 74 (21) | 52 (20) |

| ECOG 2-4 | 22 (6) | 18 (7) |

| No. involved nodal areas > 4 | 221 (64) | 176 (67) |

| No. involved extranodal sites > 1 | 51 (15) | 33 (13) |

| No. FLIPI risk factors | ||

| 1 | 49 (14) | 30 (12) |

| 2 | 138 (41) | 114 (44) |

| 3 | 91 (27) | 80 (31) |

| 4 | 55 (16) | 32 (12) |

| 5 | 5 (1) | 4 (2) |

| FLIPI risk group | ||

| Low risk | 49 (14) | 30 (12) |

| Intermediate risk | 138 (41) | 114 (44) |

| High risk | 151 (45) | 116 (45) |

Parameter . | R-CHOP,*no. (%) . | CHOP, no. (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 362 | 268 |

| Age, y, median (range) | 56 (24-90) | 57 (21-81) |

| Age 60 years or older | 137 (38) | 103 (38) |

| Male sex | 155 (43) | 141 (53) |

| Stage IV | 248 (70) | 181 (68) |

| B-symptoms present | 143 (40) | 111 (42) |

| LDH > UNL | 104 (29) | 64 (24) |

| Hb < 12 g/dL | 74 (21) | 52 (20) |

| ECOG 2-4 | 22 (6) | 18 (7) |

| No. involved nodal areas > 4 | 221 (64) | 176 (67) |

| No. involved extranodal sites > 1 | 51 (15) | 33 (13) |

| No. FLIPI risk factors | ||

| 1 | 49 (14) | 30 (12) |

| 2 | 138 (41) | 114 (44) |

| 3 | 91 (27) | 80 (31) |

| 4 | 55 (16) | 32 (12) |

| 5 | 5 (1) | 4 (2) |

| FLIPI risk group | ||

| Low risk | 49 (14) | 30 (12) |

| Intermediate risk | 138 (41) | 114 (44) |

| High risk | 151 (45) | 116 (45) |

UNL indicates upper normal limit

The R-CHOP cohort included randomized patients and patients assigned to R-CHOP after stop of randomization

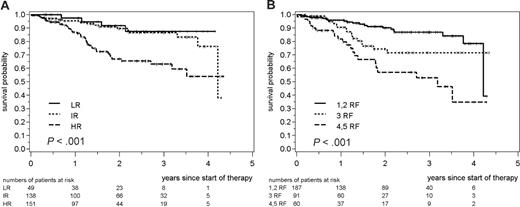

Treatment outcome according to the FLIPI after R-CHOP

After a median follow-up of 20 months, 63 of 362 patients treated with R-CHOP failed from therapy with a 2-year TTF of 80% and the median not yet reached. Patients with a high-risk FLIPI had a 2-year TTF of 67%, which was significantly lower than the 2-year TTFs observed for LR (92%) and IR (90%) patients (P < .001 for the 3-group comparison, Figure 1A). In contrast, LR and IR patients showed an almost identical TTF (P = .62). Compared with the combined low- and intermediate-risk group, patients in the high-risk group had a relative risk for treatment failure of 3.0 (95% CI 1.7 to 5.1).

In the multivariate analysis including the individual FLIPI risk factors, a serum LDH level higher than the upper normal limit (relative risk 2.6; 95% CI 1.5 to 4.5) and a hemoglobin level below 12 g/dL (relative risk 2.5; 95% CI 1.4 to 4.3) were independently associated with a shorter TTF. In contrast, age (≥ 60 years versus < 60 years; relative risk 0.9; 95% CI 0.5 to 1.5) and number of nodal areas (> 4 versus ≤ 4; relative risk 1.5; 95% CI 0.8 to 2.6) did not significantly influence the TTF in our cohort.

The FLIPI also separated HR from IR or LR patients with regard to response duration (RD). The 2-year RD in HR patients was 69% compared with 88% for LR and 89% for IR patients (P < .001; relative risk of HR to LR or IR 3.3; 95% CI 1.8 to 6.0). With regard to postinduction treatment, the index separated the HR from the IR/LR group for the patients treated with consolidating myeloablative therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT; n = 65; relative risk 6.0; 95% CI 1.4 to 25.2) as well as for the patients treated with IFN maintenance (n = 166) or no further therapy (n = 76; relative risk 3.2; 95% CI 1.8 to 5.8). With an overall response rate of 96% in the total cohort, no significant differences between the 3 FLIPI subgroups could be seen (overall response rate of 100% in LR, 97% in IR, and 95% in HR patients; P = .31). With regard to overall survival, no event was observed in 54 LR patients, 2 events were observed in 152 IR patients, and 10 events observed in 166 HR patients, resulting in 2-year OS rates of 100%, 99%, and 92% (P = .012). However, the number of events was still low, given the comparatively short follow-up.

Time to treatment failure of patients with advanced-stage FL treated with front-line R-CHOP. (A) Patients were grouped into 3 different risk groups as previously published (LR, 0 or 1 risk factor; IR, 2 factors; HR, 3-5 factors)7 or (B) analyzed separately according to the number of risk factors (RF) as indicated. The statistical significance between the 3 risk groups is shown.

Time to treatment failure of patients with advanced-stage FL treated with front-line R-CHOP. (A) Patients were grouped into 3 different risk groups as previously published (LR, 0 or 1 risk factor; IR, 2 factors; HR, 3-5 factors)7 or (B) analyzed separately according to the number of risk factors (RF) as indicated. The statistical significance between the 3 risk groups is shown.

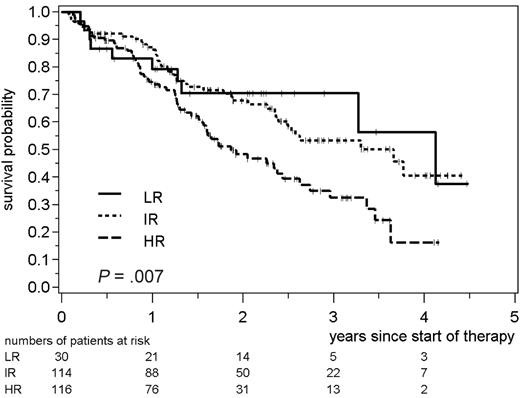

Treatment outcome according to the FLIPI after CHOP

The FLIPI also showed a significant impact on the TTF of 260 patients treated in the CHOP arm of the trial (P = .007). The HR group (n = 116; 2-year TTF 48%) was clearly separated from the IR group (n = 114; 2-year TTF 68%), and from the LR group (n = 30; 2-year TTF 70%, Figure 2). The relative risk for treatment failure of HR FLIPI patients as compared with LR or IR patients was 1.8 (95% CI 1.2 to 2.6). With regard to RD, the FLIPI also separated HR from IR or LR patients (relative risk 2.0; 95% CI 1.4 to 3.1). When the postremission therapy was taken into consideration, the index separated HR patients from the IR/LR patients for the group, which received IFN maintenance (n = 133) or no further therapy (n = 53) after initial cytoreduction (relative risk 2.8; 95% CI 1.4 to 5.4). This separation was not seen in the subgroup of responding patients, which was treated with consolidating ASCT; however, the patient number was limited in this cohort (n = 45; relative risk 2.1; 95% CI 0.55 to 8.0).

Time to treatment failure of patients with advanced-stage FL treated with front-line CHOP. Patients were grouped into 3 different risk groups as previously published (LR, 0 or 1 risk factor; IR, 2 factors; HR, 3-5 factors).7 The statistical significance between the 3 risk groups is indicated.

Time to treatment failure of patients with advanced-stage FL treated with front-line CHOP. Patients were grouped into 3 different risk groups as previously published (LR, 0 or 1 risk factor; IR, 2 factors; HR, 3-5 factors).7 The statistical significance between the 3 risk groups is indicated.

Taken together, the analysis shows that the FLIPI is able to separate HR patients from patients with an IR or LR profile after initial therapy with the rituximab/chemotherapy combination R-CHOP. The discriminative power of the FLIPI after immunochemotherapy was also documented when the postremission therapy was taken into consideration. These observations underline that the FLIPI is a robust tool to identify HR patients in the era of rituximab/chemotherapy approaches and divergent postinduction treatments. Of note, there were no significant differences for the TTF between IR and LR patients treated with R-CHOP induction or CHOP. There might be several reasons such as the relatively small number of patients and events in the LR group due to the inclusion criteria of the trial. Furthermore, this study was based on TTF and not on overall survival and incorporated rituximab into the front-line treatment strategy in comparison to the original report of the FLIPI. In addition, postremission therapy as offered to patients in this study might influence the ability of the FLIPI to discriminate between LR and IR groups.7 However, in an explorative analysis, when patients with 1 or 2 risk factors (55% of the patients), patients with 3 risk factors (27%), and patients with 4 or 5 risk factors (18%) were regrouped, a significant separation of 3 distinct risk groups could be achieved (2-year TTF 90% vs 74% vs 57%, respectively; P < .001, Figure 1B). These results suggest that after rituximab/chemotherapy with its increased antilymphoma activity, a modified definition of risk groups may facilitate the discrimination of LR and IR patient groups with regard to TTF.

Our results are in concordance with recent results of a smaller study (n = 132).13 In this trial patients were treated with R-CVP. The assessment of the FLIPI revealed that HR patients had a median TTP of only 26 months as compared with 39 months for IR patients and a median not reached for LR patients.

Hence, the FLIPI remains a useful tool for the pretherapeutic assessment of treatment outcome and for the development of risk-adapted treatment strategies in patients with FL. It also provides the basis for interstudy comparisons and for judging the impact of different treatment strategies on the outcome of distinct subgroups of patients. The FLIPI therefore promises to facilitate further improvements in FL therapy and is an important step forward toward individualized treatment concepts.

Appendix

The following persons and centers of the GLSG treated and documented the patients:

Guggenberger, Tummes, Weinberg, Praxis Aachen; Groß, v. Weikersthal, Klinikum St. Marien Amberg; Niemann, Steinmetz, St. Nikolaus Stift Hospital Andernach; Hahn, Müller, Praxis Ansbach; Schlimok, Schmid, Zentralklinikum Augsburg; Brudler, Heinrich, Bangerter, Praxis Augsburg; Langer, Meusner, Ubbo-Emmius-Klinik Aurich; Paliege, Majunke, Klinikum Bad Hersfeld; Schüßler, Namberger, Städt. Krankenhaus Bad Reichenhall; Fuss, Frenzel, Wruck, Humaine Klinikum Bad Saarow; Seipelt, Praxis Bad Soden; Schmelz, Steinmaier, Ermstal-Klinik Bad Urach; Nikolaidis, St. Elisabeth Hospital Beckum; Culmann, Höpner, Praxis Bergisch Gladbach; Thiel, Uharek, Charité - Campus Benjamin Franklin Berlin; Hellriegel, Hackenthal, Simon, Krankenhaus am Urban Berlin; Possinger, Siegert, Sezer, Univ.-Klinik Charité/Campus Mitte Berlin; Ludwig, Matylis, Helios Klinikum Berlin, Robert Rössle Klinik Berlin; Koschuth, Kingreen, Praxis Berlin; Schmidt, Schneider, Praxis Berlin; Strohbach, Zuchold, Versorgungszentrum Berlin; Blau, Fachärztin für Innere Medizin Berlin; Weh, Angrick, Franziskus Hospital Gem. Gmbh Bielefeld; Schäfer, Just, Praxis Bielefeld; Schmiegel, Graeven, Universitätsklinik Bochum; Enserweis, Praxis Bochum; Vetter, Fronhoffs, Universitätsklinik Bonn; Ko, Johanniter Krankenhaus Bonn; Wörmann, Jordan, Pies, Städtisches Klinkum Braunschweig; Pflüger, Diekmann, Ev. Diakonie-Krankenhaus Ggmbh Bremen; Obst, Praxis Burgwedel; Hollerbach, Allgemeines Krankenhaus Celle; Lohmann, Krankenhaus Coesfeld; Peter, Carl-Thiem-Klinikum Cottbus; Grünhagen, Praxis Cottbus; Fritze, Rost, Klinikum Darmstadt; Kleinsorge, Praxis Detmold; Pielken, Hagen, St. Johannes Krankenhaus Dortmund; Berger, Lamberts, Knappschaftskrankenhaus Dortmund; Wegener, Terhardt-Kasten, Malteserkrankenhaus St. Anna Duisburg; Dresemann, Lünnemann, Franz-Hospital Dülmen; Schmutz, Hegener-Tschochner, Praxis Düsseldorf; Schütte, Schneider, Artmann, Marien Hospital Düsseldorf; Becker, Meier, Klinikum Emden-Hans Susemil Kh Ggmh Emden; Rösler, Universitätsklinik Erlangen; Eckart, Häcker, Praxis Erlangen; Fuchs, Wehle-Ilka, St.-Antonius-Hospital Eschweiler; Dührsen, Nückel, Klinik und Poliklinik Essen; Saal, Hartwigsen, Benk, St.-Franziskus-Hospital Flensburg; Jäger, Krankenhaus Nordwest Frankfurt; Reiber, Nahler, Praxis Freiburg; Mertelsmann, Finke, Universitätsklinik Freiburg i. Br.; Faßbinder, Höffkes, Klinikum Fulda; Grunst, Lambertz, Schulz, Klinikum Garmisch-Partenkirchen; Brücher, Ababei, Robert-Koch-Krankenhaus Gehrden; Schmitt, Praxis Gerlingen; Schliesser, Praxis Giessen; Hoyer, Bethge, Harzkliniken Goslar; Trümper, Glaß, Binder, Universitätsklinik Göttingen; Thoms, Praxis Grefrath; Dölken, Hirt, Kränzle, Universitätsklinik Greifswald; Scholten, Hanrath, Schlotzhauer, Allgemeines Krankenhaus Hagen; Eimermacher, Lindemann, Kath. Krankenhaus Gem. Gmbh Hagen; Kraus, Hausbrandt, St. Salvator Krankenhaus Halberstadt; Schmoll, Wolf, Universitätsklinik; Hurtz, Rohrberg, Schmidt, Praxis Halle/Saale; Spohn, Praxis Halle/Saale; Schmitz, Nickelsen, Asklepios Klinik St. Georg Hamburg; Zander, Kröger, Renges, Universitätsklinik Hamburg; Bokemeyer, Universitätsklinik Hamburg; Verpoort, Zeller, Praxis Hamburg; Brüllke, Faak, Allgemeines Krankenhaus Barmbek Hamburg; Dürk, Metzner, St.-Marien-Hospital Gem. Gmbh Hamm; Kirchner, Sosada, Klinikum Hannover-Siloah; Leonhardt, Ev. Diakoniewerk Friederikenstift Hannover; Henne, Hämatologie und Internistische Onkologie Hechingen; Ho, Klinik - Innere Medizin V Heidelberg; Porowski, Praxis Heilbronn; Schmitz-Huebner, Lange, Nguyen, Klinikum Kreis Herford; Voigtmann, Schilling, Marienhospital Herne; Hahn, Praxis-Klinik Herne; Freier, Praxis Hildesheim; Pfreundschuh, Universitätsklinik Homburg/Saar; Kruse, Don, St. Ansger Krankenhaus Höxter; Fauser, Klinik für KMT Idar-Oberstein; Verth, Böse, Klinikum Itzehoe Itzehoe; Höffken, Fricke, Wedding, Universitätsklinik Jena; Hahnfeld, Krombholz, Praxis Jena; Mezger, Göckel, St.-Vincentius-Krankenhäuser Karlsruhe; Siehl, Söling, Praxis Kassel; Prümmer, Gatter, Börner, Klinikum Kempten-Oberallgäu Ggmbh Kempten; Kneba, Universitätsklinik Kiel; Kloos, Kreiskrankenhaus Kirchheim; Dormeyer, van Roye, Skm Ev. Stift St. Martin Koblenz; Hallek, Reiser, Universitätsklinik Köln; Schmitz, Steinmetz, Praxis Köln; Helmer, Nowak, Städt. Krankenanstalten Krefeld; Stauch, Praxis Kronach; Karbach, Schröder, Vinzentius-Krankenhaus Landau/Pfalz; Schumann, Schunk, Städt. Krankenhaus Landau/Pfalz Landau/Pfalz; Vehling-Kaiser, Praxis Landshut; Kremers, Täger, Caritas Krankenhaus Lebach; Müller, Praxis Leer; Aldaoud, Schwarzer, Praxis Leipzig; Mantovani, B. Matth, Schulz-Abelius, Städt. Klinikum St. Georg Leipzig; Hartmann, Middeke, Klinikum Lippe-Lemgo Gmbh Lemgo; Heidenreich, Jost, Dreifaltigkeitshospital Lippstadt; Fetscher, Schmelar, Sana Kliniken - Krankenhaus Süd Lübeck; Wagner, Peters, Universitätsklinik Lübeck; Heil, Trebing-Lukas, Klinikum Lüdenscheid; Uppenkamp, Hoffmann, Klinikum der Stadt Ludwigshafen; Weiss, St.-Marien-Krankenhaus Ludwigshafen; Königsmann, Holmer, Universitätsklinik Magdeburg; Kettner, Krötki, Städtisches Klinikum/KH Altstadt Magdeburg; Huber, Fischer, Heß, III. Medizinische Klinik Mainz; Hehlmann, Lengfelder, Kuhn, III. Klinik Mannheim Mannheim; Neubauer, Schwella, Universitätsklinik Marburg; Pfeiffer, Mennicke, Klinikum Memmingen; Ellbrück, Praxis Memmingen; Schwonzen, St.-Walburga-Krankenhaus Meschede; Graeven, Kohl, Verbeek, Kliniken Maria Hilf Gmbh Mönchengladbach; Peschel, Schilling, Klinikum Rechts der Isar der TU München; Forstpointner, Dreyling, Hiddemann, Universitätsklinik München; Hartenstein, Brack, Städt. KH München-Harlaching München; Fromm, Borlinghaus, Sauter, Praxis München; Schlöndorff, Walther, Seybold, Klinikum Innenstadt München; Theml, Schick, Praxis München; Berdel, Universitätsklinik Münster; Wehmeyer, Lerchenmüller, Kratz-Albers, Praxis Münster; Pauw, Städt. Krankenhaus Nettetal; Maurer, v. Bierbrauer, Staedt. Krankenhaus Neunkirchen; Schmidt, Praxis Neunkirchen; Czygan, Lukaskrankenhaus Neuss Neuss; Hoffmann, Praxis Norderstedt; Wilhelm, Wandt, Lechner, Klinikum Nürnberg - 5. Klinik Nürnberg; Schauer, Praxis Nürnberg; Bair, Zellmann, Schlossberg Klinik Oberstaufen; Böck, Ballo, Praxis Offenbach; Henning-Köhne, Metzner, Klinikum Oldenburg Ggmbh; Otremba, Zirpel, Praxis; Wolff, Niemeyer, Brüderkrankenhaus St. Josef Paderborn; Skusa, Asklepios Klinik Parchim; Gmelin, Klinik D. Siloah Krankenhauses Pforzheim; Maschmeyer, Rothmann, Haas, Ernst-Von-Bergmann-Klinik Potsdam; Andreesen, Krause, Mayer, Universitätsklinik Regensburg; Kreuser, Krankenhaus Barmherzige Brüder Regensburg; Günther, Kreiskrankenhaus Reutlingen; Raschke, Jakobi-Krankenhaus Rheine; Krause, Kreiskrankenhaus Rinteln; Huff, Schönberger, Puchtler, Klinikum Rosenheim; Neeck, Krammer-Steiner, Klinikum Südstadt Rostock; Freund, Universitätsklinik Rostock; Lakner, Decker, Praxis Rostock; Baldus, Praxis Rüsselsheim; Preiß, Schmidt, Caritas Klinik St. Theresia Saarbrücken; Daus, Jacobs, Schmits, Praxis Saarbrücken; Gassmann, Gaska, St.-Marien-Krankenhaus Siegen Siegen; Seitz, Käfer, Kreiskrankenhaus Sigmaringen Sigmaringen; Beckers, Siebert, Koller, St.-Lukas-Klinik Solingen-Ohligs; Demandt, Praxis Straubing; Mergenthaler, Schleicher, Katharinenhospital Stuttgart; Aulitzky, Martin, Robert-Bosch-Krankenhaus Stuttgart; Höring, Ehr, Respondek, Praxis Stuttgart; Mergenthaler, Golf, Bürgerhospital Stuttgart; Heidemann, Kaesberger, Diakonieklinikum Stuttgart; Fiechtner, Praxis Stuttgart; Kölbel, Weber, Kirchen, Krankenhaus der Barmherzigen Brüder Trier; Clemens, Mutterhaus der Borromäerinnen Trier; Rendenbach, Praxis Trier; Grundheber, Praxis Trier; Biedermann, Kreisklinik Trostberg; Diers, Twiessel, Marienhospital Vechta; Reiter, Facharzt für Innere Medizin Viersen; Brugger, Funke, Klinik Villingen-Schwenningen Villingen; Brettner, Bias, Kreiskrankenhaus Waldbröl; Dargel, Wilhelm, Harz-Klinikum Wernigerode Gmbh; Kehl, Schmidtova, Evangelisches Krankenhaus Wesel; Frickhofen, Fuhr, Jung, Dr.-H.-Schmidt-Kliniken Wiesbaden; Josten, Klein, Deutsche Klinik f. Diagnostik Ggmbh Wiesbaden; Augener, St.-Willehad-Hospital Wilhelmshaven; Bock, Praxis Wittenberge; Haessner, Heine, Praxis Wolfsburg; Burkhard, Reimann, Praxis Worms; Sandmann, Becker, Kliniken St. Antonius Wuppertal; Maintz, Praxis Würselen; Einsele, Weissinger, Reimer, Universitätsklinik Würzburg; Schlag, Praxis Würzburg; Kreibich, Städtisches Klinikum H. Braun Zwickau.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, May 11, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2006-01-013367.

A complete list of the members of the GLSG appears in “Appendix.”

Supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe (T14/96/Hi 1) and the Deutsches Bundesministerium für Bildung und Familie as part of the Competence Network Lymphomas.

C.B., E.H., M.D., and W.H. wrote the manuscript; C.B., M.D., M.U., and W.H. planned the study and wrote the study protocol; C.B., W.H., M.D., and M.U. treated and documented patients; E.H., J.H., and M.U. monitored the study, performed statistical evaluation, and wrote the study report.

C.B. and E.H. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal