Abstract

Erdheim-Chester disease is a rare non-Langerhans histiocytosis with multisystem involvement. To date, there is no standard treatment for this disorder, and more than half of the patients succumb within 3 years. Because interferon-α promotes the terminal differentiation of histiocytes and dendritic cells, we hypothesized that this molecule would be a useful therapy for Erdheim-Chester disease. We therefore treated 3 patients with advanced disease with interferon-α at a starting dose of 3 to 6 × 106 units, which was later reduced, during maintenance, to 1 × 106 units subcutaneous 3 times per week. Marked improvement was noted in all patients, with substantial retro-orbital disease regression within 1 month. Improvement in bone lesions, pain, diabetes insipidus, and other manifestations was gradual over many months. Responses were durable (3+ to 4.5+ years). Our observations suggest that this well-tolerated therapy has a significant effect on the course and outcome of Erdheim-Chester disease.

Introduction

In 1930, William Chester described the first 2 cases of “lipoid granulomatosis,” later renamed Erdheim-Chester disease.1 This illness represents a rare non-Langerhans histiocytosis with particular tropism for connective and adipose tissues. Clinical features range from a focal asymptomatic process to a multisystem, rapidly fatal, infiltrative disease with a total of about 250 cases described in the literature.2-7 Typically, it affects adults of both sexes, with symmetric osteosclerosis of the long bones sparing the epiphyses.2,3 The histiocytes mainly infiltrate bones, pituitary, orbit, retroperitoneum, and central nervous system.2-5 The pathology is characterized by large, foamy, or eosinophilic cytoplasm lipidladen CD68+, CD1a–, and S100– histiocytes lacking any Birbeck granules, and the pathognomonic Touton-like giant cells, which are multinucleated cells with the nuclei organized in a wreathlike ring and a xanthomatous cytoplasm.4,6,8

There is no standard treatment for Erdheim-Chester disease. Unfortunately, about 60% of patients succumb to their disease within 32 months of presentation.2 Of interest, researchers reported that interferon-α results in terminal differentiation of histiocytes and dendritic cells.9,10 We therefore administered interferon-α to 3 patients with Erdheim-Chester disease. This treatment resulted in durable responses, with the longest ongoing at 4 years.

Study design

Patient 1

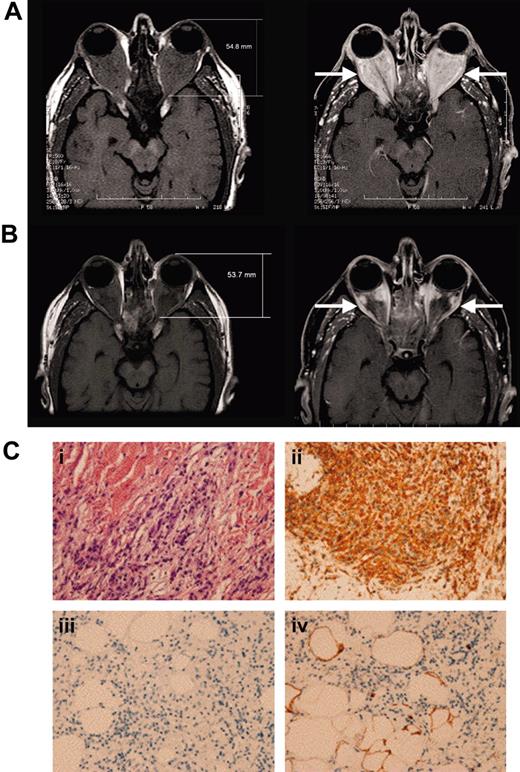

A 55-year-old man with a 4-year history of diabetes insipidus, presented with rapidly decreasing vision, orbital pain, and striking exophthalmos. Previous medical history included hairy-cell leukemia, which had been in complete remission for several years after treatment with 2-chlordeoxyadenosine. The ophthalmologic examination revealed restricted extraocular movements, bilateral visual acuity of 20/30, and a Hertel exophthalmometry measurement of 23 mm (normal, 12-20 mm). Fundal examination suggested compressive optic neuropathy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbit showed massive retrobulbar infiltration (Figure 1A). Bone marrow aspiration and thyroid panels were normal. The patient's vision and orbital pain continued to worsen (20/80 in the right eye and 20/200 in the left eye), with severe bilateral visual field deficit despite high doses of corticosteroids. The diabetes insipidus, ocular symptoms, and the technetium-99m labeled methylene diphosphonate (99mTc-MDP) bone scan findings of diffuse osteosclerosis of the long bones was compatible with the diagnosis of Erdheim-Chester disease. Furthermore, abdominal computed tomography scan revealed perinephric soft tissue infiltrate, and biopsy was consistent with Erdheim-Chester disease (Figure 1C).

The patient was treated with 3 × 106 units subcutaneous interferon-α 3 times per week. Within 1 month he was able to taper off corticosteroids and showed recovery of his visual acuity and visual fields. Repeat MRI of the orbits 3 months later showed substantial improvement.11 The patient's persistent fatigue resolved with a reduction of the interferon-α dose down to 1 × 106 units 3 times per week. Four years later, the patient remains asymptomatic on this maintenance dose. His MRI scan shows further decrease in his retro-orbital mass size and its inflammatory activity (Figure 1B). His diabetes insipidus has also improved with a 87.5% reduction of his daily desmopressin dose.

Patient 2

A 58-year-old man was evaluated for ongoing leg pain, treated diabetes insipidus, and panhypopituitarism. The long bone radiographs of his legs showed bilateral osteosclerosis of the diaphyses and metaphyses sparing the epiphyses of the femur and tibia. A right femur bone biopsy revealed infiltration with diffuse large foamy histiocytes, Touton-like giant cells and lymphocytic aggregates and fibrosis diagnostic of Erdheim-Chester disease. 99mTc-MDP bone scan identified multiple long bone lesions as well as T11 thoracic and L3 lumbar vertebral lesions. Unfortunately, neither radiotherapy to his spine and knees nor strontium-90 radionuclide nor high-dose prednisone halted the ongoing progression of his disabling pain syndrome requiring high-dose opioids. Interferon-α, 3 × 106 units subcutaneous 3 times per week, later decreased to 1 × 106 units because of significant fatigue was very well tolerated and allowed tapering down his opioids within 3 months (Figure 2A). After 2.5 years of interferon-α maintenance therapy, he is pain free and off analgesics, and the follow-up tests show significant improvement of the bone radiographs (Figure 2B).

Retro-orbital and retroperitoneal disease in patient 1. (A) Before interferon-α, extensive retrobulbar soft tissue mass (arrows) is seen on the T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging before (left) and after (right) gadolinium injection. (B) After 4 years of continuous interferon-α treatment, the extent of retrobulbar infiltration (arrows) continues to decrease substantially. (Ci) Perinephric adipose tissue reveals large foamy lipid-laden histiocytes with eosinophilic cytoplasm; (ii) staining positive for CD68, (iii) but staining negative for CD1a; and (iv) staining negative for S100 (< 5% positive). Images were acquired at a magnification of 200 × using a Nikon Microphot-FXA microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) fitted with a 20 × phase-contrast objective lens (PlanApo 20 ×/0.75 NA). Images were captured with a digital camera, model DP-70 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), using DP 12 image-acquisition software (Olympus), DP-70 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), using DP 12 image-acquisition software (Olympus), and image-processing was carried out using Microsoft PowerPoint (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Retro-orbital and retroperitoneal disease in patient 1. (A) Before interferon-α, extensive retrobulbar soft tissue mass (arrows) is seen on the T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging before (left) and after (right) gadolinium injection. (B) After 4 years of continuous interferon-α treatment, the extent of retrobulbar infiltration (arrows) continues to decrease substantially. (Ci) Perinephric adipose tissue reveals large foamy lipid-laden histiocytes with eosinophilic cytoplasm; (ii) staining positive for CD68, (iii) but staining negative for CD1a; and (iv) staining negative for S100 (< 5% positive). Images were acquired at a magnification of 200 × using a Nikon Microphot-FXA microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) fitted with a 20 × phase-contrast objective lens (PlanApo 20 ×/0.75 NA). Images were captured with a digital camera, model DP-70 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), using DP 12 image-acquisition software (Olympus), DP-70 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), using DP 12 image-acquisition software (Olympus), and image-processing was carried out using Microsoft PowerPoint (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Patient 3

A 53-year-old man presented with a bilateral periorbital congestion, erythema, and proptosis. Exophthalmos was confirmed by Hertel exophthalmometry measurements of 27 mm. MRI scan of the orbit showed bilateral intraconal masses with increased signal on T2-weighted images.

Long bone radiographs revealed a localized area of fibrous sclerosis in the distal left fibula. Computed tomography scans of the abdomen demonstrated retroperitoneal fibrosis. Retro-orbital mass biopsy demonstrated Touton giant cells with CD68+, S100–, and CD1a– histiocytic infiltrate, confirming the diagnosis of Erdheim-Chester disease. The patient's visual acuity and exophthalmos worsened despite therapy with methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, and high-dose prednisone and vincristine.

Interferon-α was started, but the initial dose of 6 × 106 units subcutaneous 3 times per week was reduced 6 months later to 3 × 106 units and 4 months afterward to 1 × 106 units because of fatigue. The patient tolerated low-dose interferon-α well and continued on it for an additional 16 months. Therapy was stopped because the patient's eye examination had normalized (Figure 2C). Eight months later, new skin lesions were noted, and biopsy confirmed relapse. Interferon-α was recently restarted, and the patient again demonstrated response.

Response to interferon-α in patients 2 and 3. (A) Morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD; mg/d) needed to manage pain before and after interferon-α therapy. Patient required 120 mg/d opioids before starting interferon-α. After 2 years, he no longer needs opioids. (B) Bone radiograph of the right femur reveals mixed osteosclerotic and osteolytic lesions before treatment. Ongoing improvement is seen after 2 years of treatment with interferon-α. (C) (Top) Bilateral exophthalmos with chemosis, engorged conjunctival vessels, and inferior scleral show (arrows) at presentation. Loss of eyelashes because of recent chemotherapy is noted. (Bottom) Exophthalmos, chemosis, and inferior scleral show (arrows) resolved after 2 years of interferon-α. Eyelashes have grown back.

Response to interferon-α in patients 2 and 3. (A) Morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD; mg/d) needed to manage pain before and after interferon-α therapy. Patient required 120 mg/d opioids before starting interferon-α. After 2 years, he no longer needs opioids. (B) Bone radiograph of the right femur reveals mixed osteosclerotic and osteolytic lesions before treatment. Ongoing improvement is seen after 2 years of treatment with interferon-α. (C) (Top) Bilateral exophthalmos with chemosis, engorged conjunctival vessels, and inferior scleral show (arrows) at presentation. Loss of eyelashes because of recent chemotherapy is noted. (Bottom) Exophthalmos, chemosis, and inferior scleral show (arrows) resolved after 2 years of interferon-α. Eyelashes have grown back.

Approval was obtained from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center institutional review board for these studies. Informed consent was provided in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results and discussion

Erdheim-Chester disease is a rare non-Langerhans histiocytosis of unknown etiology. The outcome of patients with Erdheim-Chester disease is worse than that for Langerhans-cell histiocytosis with 59% of patients in the former group dead after a mean follow-up of 32 months,2 whereas only 9% of patients with the latter disorder have succumbed after a median follow-up of 4 years.12

Numerous treatments have been attempted for this disease.2,6,13,14 Corticosteroids are the traditional first-line treatment and are used to control symptoms, but generally they are either ineffective or only transiently effective.2,6 Bisphosphonates are efficient in treating osteolytic lesions in Langerhans-cell histiocytosis but have only partial or temporary success in the management of bone involvement in Erdheim-Chester disease.15 Chemotherapy can induce transient partial responses but is often ineffective.2,16 Cladribine has been used successfully in adult Langerhans histiocytosis, but its application in Erdheim-Chester disease is limited to 2 patients, one of whom responded.16,17 Radiation, methotrexate, cyclosporine, and azathioprine have not yielded sustained clinical response.3,18-20

We describe the successful treatment of 3 patients with ErdheimChester disease with interferon-α. The initial therapeutic dose of 3 to 6 × 106 units subcutaneous 3 times per week was reduced to 1 × 106 units 3 times per week because of fatigue. This low dose was well tolerated, and response was observed within 1 month with dramatic reduction in the exophthalmos and recovery of vision in 2 patients (cases 1 and 3) whose vision was threatened by progressive disease while on high-dose chemotherapy and/or steroids. Response was also manifested by gradual improvement in diabetes insipidus (cases 1 and 2) and in bone lesions (case 2) (Figure 2).

The mechanism(s) underlying the salutary effects of interferon-α in Erdheim-Chester are unclear but could be due to several of the diverse biologic effects of this agent: maturation and activation of dendritic cells,9,10 immune-mediated (eg, via natural killer cells) destruction of histiocytes, or direct antiproliferative effects.21 There is also anecdotal evidence of clinical therapeutic benefits for interferon-α in other histiocytic disorders (Langerhanscell histiocytosis22 and Rosai-Dorfaman disease23 ).

Erdheim-Chester disease is a rare and difficult-to-treat disease. All 3 of our patients with this disorder achieved a long-lasting response (3+, 3.5, and 4.5+ years) while receiving interferon-α. Our observations suggest that this well-tolerated treatment warrants further application and investigation in this disorder.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 14, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2238.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal