Abstract

The t(11;18)(q21;q21) translocation is a specific marker for Helicobacter pylori–independent status of low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. However, there are no reliable markers to predict tumor response to H pylori eradication in patients without t(11;18)(q21;q21). Nuclear expression of BCL10 and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) was recently found to be closely associated with H pylori–independent status of the high-grade counterpart of gastric MALT lymphoma, which usually lacks t(11;18)(q21;q21). This study examined whether these 2 markers can also predict H pylori–independent status of low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas without t(11; 18)(q21;q21). Sixty patients who underwent successful H pylori eradication for low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas were included. Forty-seven (78.3%) patients were negative for t(11;18)(q21;q21); among them, 36 (76.6%) were H pylori dependent and 11 (23.4%) were H pylori independent. Nuclear expression of BCL10 was significantly higher in H pylori–independent than in H pylori–dependent tumors (8 of 11 [72.7%] vs 3 of 36 [8.3%]; P < .001). Nuclear expression of NF-κB was also significantly higher in H pylori–independent than in H pylori–dependent tumors (7 of 11 [63.6%] vs 3 of 36 [8.3%]; P < .001). Further, nuclear translocation of BCL10 and NF-κB was observed in 12 of the 13 patients with t(11;18)(q21;q21), and all these 12 patients were H pylori independent. In summary, nuclear expression of BCL10 or NF-κB is predictive of H pylori–independent status of low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma with or without t(11;18)(q21; q21).

Introduction

Gastric mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma represents the most common type of MALT lymphoma and is characterized by its close association with Helicobacter pylori infection.1,2 Eradication of H pylori by antibiotics cures approximately 70% of this tumor.3 Although t(11;18)(q21;q21) is one of the most important predictors of H pylori independence in low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas, only 50% to 70% of H pylori–independent low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas harbor this genetic aberration.4-6 In other words, 30% to 50% of H pylori–independent low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas have no reliable markers to predict their H pylori–independent status. Therefore, identification of other easily detected molecular markers that can provide high sensitivity in predicting H pylori–independent status of low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas without t(11;18)(q21;q21) is mandatory.

Several genetic changes are implicated in the development of gastric MALT lymphoma. One of the most important genetic aberrations, t(1;14)(p22;q32) juxtaposes the BCL10 gene of chromosome 1p to the immunoglobulin gene locus of chromosome 14q and results in strong expression of a truncated BCL10 protein in the nuclei and cytoplasm.7,8 However, most MALT lymphomas with BCL10 nuclear localization do not have genetic aberrations of t(1;14)(p22;q32) or other BCL10 gene mutations.9-12 Surprisingly, BCL10 nuclear expression was found to be more closely associated with the genetic aberration t(11;18)(q21;q21), which is a specific marker for H pylori independence of low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma.13 In B lymphocyte, BCL10 is an intracellular protein that positively regulates lymphocyte proliferation by linking antigen receptor stimulation to activate nuclear kappa factor B (NF-κB) signaling.14,15 Moreover, the chimeric protein of t(11; 18)(q21;q21) itself leads to constitutive NF-κB activity through self-oligomerization of the baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR) domain of the API2 molecule.16 Because NF-κB is known to mediate cell survival and antiapoptotic signals,17 it has been speculated that its up-regulation may contribute to the malignant transformation of H pylori–independent growth of MALT lymphomas.

Recently, we demonstrated that a substantial portion of high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas remain H pylori dependent and can be cured by H pylori eradication.18 We also clarified that nuclear translocation of BCL10 or NF-κB is the pivotal molecular determinant of H pylori independence in high-grade gastric MALT lymphoma and that coexpression of these 2 markers in the nuclei is frequent.19 Given that t(11;18)(q21;q21) rarely occurs in high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas,20,21 it is reasonable to speculate that nuclear translocation of BCL10 and NF-κB may also be useful for predicting H pylori–independent status of low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas that lack t(11;18)(q21;q21).

In this study, we analyzed the genetic aberration of t(11;18)(q21; q21) and the expression patterns of BCL10 and NF-κB in 37 H pylori–dependent and 23 H pylori–independent low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas. We found that nuclear expression of these 2 markers is highly useful in predicting H pylori–independent status of low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas with or without t(11;18)(q21;q21).

Patients and methods

Patients, treatment, and evaluation of tumors

Sixty patients who had participated in a prospective study of H pylori eradication for localized low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas and had subsequently had their gastric H pylori infection eradicated, as defined by negative results for biopsy urease test, histology, and bacterial culture, were included in this study. The diagnosis of low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma was made according to the histologic criteria described by Chan et al.22 Tumors were characterized by the presence of predominantly low-grade centrocytelike cell infiltrates and lymphoepithelial lesions and the absence of confluent clusters or sheets of large cells resembling centroblasts or lymphoblasts and of predominantly high-grade lymphoma cells. Histopathologic characteristics of all tumor specimens were independently reviewed by 2 experienced hematopathologists. Staging was classified according to Musshoff's modification of the Ann Arbor staging system.23

At the beginning of the study, the H pylori eradication regimen consisted of amoxicillin 500 mg and metronidazole 250 mg 4 times a day with either bismuth subcitrate 120 mg 4 times a day or omeprazole 20 mg twice a day for 4 weeks, but it was changed after March 1996 to amoxicillin 500 mg 4 times a day, clarithromycin 500 mg twice a day, and omeprazole 20 mg twice a day for 2 weeks. Patients were scheduled to undergo first follow-up upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination 4 to 6 weeks after the completion of antimicrobial therapy, and follow-up was then repeated every 6 to 12 weeks until histologic evidence of remission was found. At each follow-up examination, 4 to 6 biopsy specimens were taken from the antrum and body of the stomach for the evaluation of H pylori infection, and a minimum of 6 biopsy specimens were taken from each of the tumors and suspicious areas for histologic evaluation. Diagnosis of H pylori infection was based on histologic examination, biopsy urease test, and bacterial culture. Tumor regression after eradication therapy was histologically evaluated according to the criteria of Wotherspoon et al.24 Tumors that resolved to Wotherspoon grade 2 or less after successful H pylori eradication were considered H pylori dependent. Tumors that had objective evidence of progression any time during follow-up or tumors that failed to show histologic regression 12 months after successful H pylori eradication were considered H pylori independent.5

The Institutional Review Board at National Taiwan University Hospital approved the prospective clinical trial, the pathologic review, and the genetic studies of archived tumor tissues. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Immunohistochemistry and confocal laser scanning microscopy

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections cut at a thickness of 4 μm were deparaffinized and rehydrated through xylenes and a graded alcohol series. After antigen retrieval by heat treatment in 0.1 M citrate buffer at pH 6.0, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 3% H2O2. Briefly, slides were incubated for 30 minutes in 2.5% normal donkey serum or goat serum. The slides were then incubated overnight at 4°C either with polyclonal goat anti–human BCL10 (1:10; sc-9560; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or polyclonal rabbit anti–human RelA (p65; 1:100; sc-7151; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and were incubated with secondary antibodies (BCL10, donkey anti–goat immunoglobulin; RelA, goat anti–rabbit immunoglobulin; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Finally, antibody binding was detected by the avidin-biotin-peroxidase method. Reaction products were developed using 3′, 5′-diaminobenzidine (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) as a substrate for peroxidase. Sections were counterstained with Mayer hematoxylin. All washes were performed in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4). Staining was considered positive for BCL10 or NF-κB when the protein was detected in more than 10% of tumor cells with nuclear staining.9,12 Reactive spleen and lymph node tissue sections were used as controls.

For double-immunolabeling studies, fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled donkey anti–goat immunoglobulin G (IgG) or rhodamine-labeled goat anti–rabbit IgG was incubated as a secondary antibody for 60 minutes at room temperature in the dark. The sections were further evaluated under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (model TC-SP; Leica, Heidelberg, Germany) equipped with argon and argon-krypton laser sources.

Multiplex reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction for the API2-MALT1 fusion transcript

Total cellular RNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues using an Ambion RNA isolation kit (AMS Biotechnology, Oxon, United Kingdom). Briefly, 2 to 3 pieces of 10-μm paraffin sections were deparaffinized in xylene. The tissue was digested with proteinase K (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) for 1 hour at 45°C and solubilized in a guanidinium-based buffer. RNA extracted from the paraffin-embedded tissues was analyzed for API2-MALT1 fusion using multiplex reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as described previously.21 RNA was subjected to first-round multiplex 1-tube RT-PCR, then to second-round nested multiplex PCRs (3 parallel: second PCR-A, second PCR-B, and second PCR-C). The final PCR products were run on 3% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The band size ranged from 80 to 179 bp. PCR of low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma samples known to possess API2-MALT1 fusion was used as a positive control. Beta-actin (190 bp) was amplified in parallel as an internal control. Where indicated, PCR products of the API2-MALT1 transcript were directly sequenced or were cloned into a vector (TOPO TA Cloning Kit; Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) and sequenced with vector primers using dye-labeled terminators (BigDye Terminators; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and analyzed on a DNA sequencer (model 310; Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analysis

Fisher exact test and the χ2 test were used to analyze the correlation between the H pylori–independent status of MALT lymphomas and the translocation t(11;18)(q21;q21) and expression patterns of BCL10 and NF-κB.

Results

Patients and tumor response to H pylori eradication

Thirty-seven patients were H pylori dependent, and 23 patients had H pylori–independent tumors. Clinicopathologic features of these patients and their tumor responses to H pylori eradication are summarized in Table 1. The median duration between H pylori eradication and complete histologic remission was 2.6 months (range, 0.9-17 months), and 34 of 37 (91.9%) patients did so within 12 months of H pylori eradication. The median duration between H pylori eradication and commencement of other treatments for the 23 H pylori–independent patients was 13 months (range, 4-27 months). Eight patients who had persistent or increasing epigastric discomfort and endoscopically or pathologically documented progressive tumors during regular follow-up were considered H pylori independent and were started with salvage treatments within 12 months of H pylori eradication. At a median follow-up of 69.2 months (range, 12-124 months), 35 patients who had achieved complete histologic remission after eradication of H pylori were alive and free of lymphoma. Two patients experienced histologic relapse.

Clinicopathologic features of patients and tumor responses to H pylori eradication

. | Complete remission . | No remission . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients (%) | 37 (61.6) | 23 (38.4) | NS |

| Age, y | |||

| Median (range) | 57 (35-84) | 56 (36-74) | NS |

| Sex, no. (%) | |||

| Male | 15 (40.5) | 11 (47.8) | NS |

| Female | 22 (59.5) | 12 (52.2) | |

| Stage by EUS and CT, no. (%) | |||

| Mucosa/submucosa | 26 (70.3) | 16 (69.6) | NS |

| Muscularis propria/serosa | 11 (29.7) | 7 (30.4) | |

| API2-MALT1, no. (%) | |||

| Positive | 1 (2.7) | 12 (52.2) | < .001 |

| Negative | 36 (97.3) | 11 (47.8) | |

| BCL10 expression, no. (%) | |||

| Cytoplasmic | 34 (91.9) | 3 (13.1) | < .001 |

| Nuclear/cytoplasmic | 3 (8.1) | 20 (86.9) | |

| NF-κB expression, no. (%) | |||

| Cytoplasmic | 34 (91.9) | 4 (17.4) | < .001 |

| Nuclear/cytoplasmic | 3 (8.1) | 19 (82.6) |

. | Complete remission . | No remission . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients (%) | 37 (61.6) | 23 (38.4) | NS |

| Age, y | |||

| Median (range) | 57 (35-84) | 56 (36-74) | NS |

| Sex, no. (%) | |||

| Male | 15 (40.5) | 11 (47.8) | NS |

| Female | 22 (59.5) | 12 (52.2) | |

| Stage by EUS and CT, no. (%) | |||

| Mucosa/submucosa | 26 (70.3) | 16 (69.6) | NS |

| Muscularis propria/serosa | 11 (29.7) | 7 (30.4) | |

| API2-MALT1, no. (%) | |||

| Positive | 1 (2.7) | 12 (52.2) | < .001 |

| Negative | 36 (97.3) | 11 (47.8) | |

| BCL10 expression, no. (%) | |||

| Cytoplasmic | 34 (91.9) | 3 (13.1) | < .001 |

| Nuclear/cytoplasmic | 3 (8.1) | 20 (86.9) | |

| NF-κB expression, no. (%) | |||

| Cytoplasmic | 34 (91.9) | 4 (17.4) | < .001 |

| Nuclear/cytoplasmic | 3 (8.1) | 19 (82.6) |

EUS indicates endoscopic ultrasonography; CT, computed tomography; NS, not significant.

API2-MALT1 fusion transcript of t(11;18)(q21;q21)

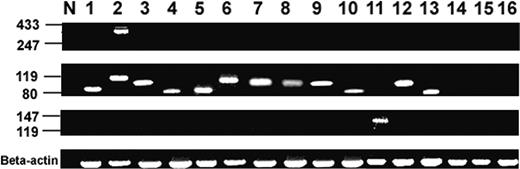

The API2-MALT1 fusion transcript for t(11;18)(q21;q21) was detected in 13 (21.7%) patients (Figure 1). Sequencing analysis of the RT-PCR products confirmed the presence of API2-MALT1 fusion transcript in all 13 patients, and the characteristics of all API2-MALT1 fusion variants were in keeping with those reported previously.21

Detection of t(11;18)(q21;q21) by multiplex RT-PCR of the API2-MALT1 fusion transcript. Blots from top to bottom: second PCR-A, second PCR-B, second PCR-C, and beta-actin mRNA amplification. Lane N, negative control (normal lymph node). Lanes 1 to 12, H pylori–independent MALT lymphomas (positive). Lane 13, H pylori–dependent MALT lymphoma (positive). Lanes 14 to 16, H pylori–dependent MALT lymphomas (negative).

Detection of t(11;18)(q21;q21) by multiplex RT-PCR of the API2-MALT1 fusion transcript. Blots from top to bottom: second PCR-A, second PCR-B, second PCR-C, and beta-actin mRNA amplification. Lane N, negative control (normal lymph node). Lanes 1 to 12, H pylori–independent MALT lymphomas (positive). Lane 13, H pylori–dependent MALT lymphoma (positive). Lanes 14 to 16, H pylori–dependent MALT lymphomas (negative).

Correlation of nuclear expression of BCL10 and NF-κB with tumor response to H pylori eradication in low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma without t(11;18)(q21;q21)

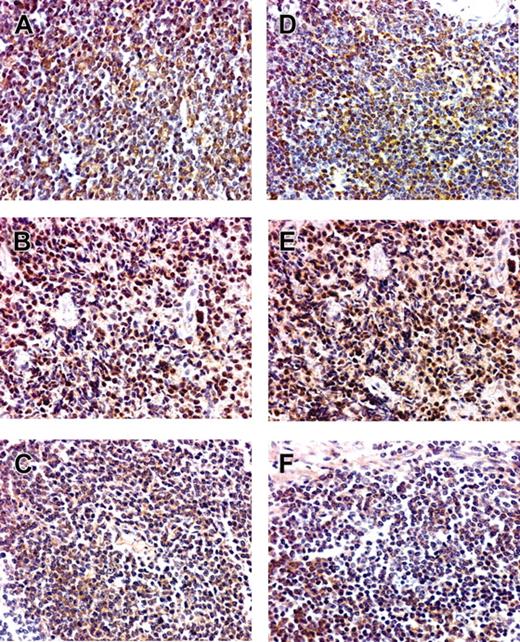

Among the 47 patients without t(11;18)(q21;q21), the frequency of nuclear expression of BCL10 was significantly higher in H pylori–independent than in H pylori–dependent tumors (8 of 11 [72.7%] vs 3 of 36 [8.3%]; P < .001) (Table 1; Figure 2). The frequency of nuclear expression of NF-κB was also significantly higher in H pylori–independent tumors than in H pylori–dependent low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas (7 of 11 [63.6%] vs 3 of 36 [8.3%]; P < .001) (Table 1). Nuclear coexpression of these 2 markers was seen in 4 tumors examined by confocal microscopy. The nuclear expression of BCL10 had a sensitivity of 72.7% and a specificity of 91.7% in predicting H pylori independence of low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas without t(11;18)(q21;q21). The nuclear expression of NF-κB had a sensitivity of 63.6% and a specificity of 91.7% in predicting H pylori independence of low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas without t(11;18)(q21;q21).

Correlation of nuclear expression of BCL10 and NF-κB with tumor response to H pylori eradication in patients with low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma patients t(11;18)(q21;q21)

As expected, 12 (92.3%) of the 13 patients with t(11;18)(q21;q21) had H pylori–independent lymphoma. The MALT lymphoma of all these 12 patients had nuclear translocation of both BCL10 and NF-κB (Figure 3). The only tumor with the genetic aberration of t(11;18)(q21;q21) but a cytoplasmic location of BCL10 and NF-κB was H pylori dependent.

BCL10 and NF-κB protein expression in low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas with and without t(11;18)(q21;q21). (A-C) BCL10. (D-F) NF-κB. (A,D) Nuclear BCL10 and NF-κB expression in H pylori–independent patients with t(11;18)(q21;q21). (B,E) Nuclear BCL10 and NF-κB expression in H pylori–independent patients without t(11;18)(q21;q21). (C,F) Cytoplasmic BCL10 expression and NF-κB expression in H pylori–dependent patients. Original magnification, × 400. An Olympus BX40 microscope equipped with 10×/0.25 and 40×/0.65 objective lenses (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to visualize images. Pictures were taken with an Olympus DP11 camera, and Adobe Photoshop 6.0 was used to zoom images to their present magnitude (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

BCL10 and NF-κB protein expression in low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas with and without t(11;18)(q21;q21). (A-C) BCL10. (D-F) NF-κB. (A,D) Nuclear BCL10 and NF-κB expression in H pylori–independent patients with t(11;18)(q21;q21). (B,E) Nuclear BCL10 and NF-κB expression in H pylori–independent patients without t(11;18)(q21;q21). (C,F) Cytoplasmic BCL10 expression and NF-κB expression in H pylori–dependent patients. Original magnification, × 400. An Olympus BX40 microscope equipped with 10×/0.25 and 40×/0.65 objective lenses (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to visualize images. Pictures were taken with an Olympus DP11 camera, and Adobe Photoshop 6.0 was used to zoom images to their present magnitude (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

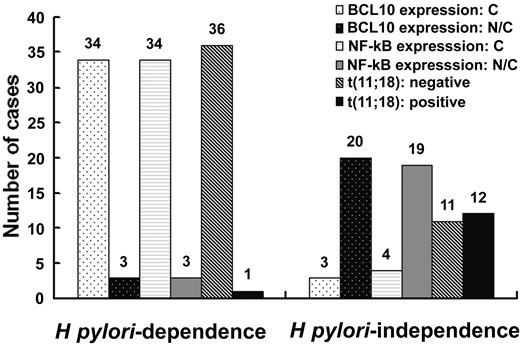

Correlation between H pylori independence and API2-MALT1 fusion transcript and nuclear expression of BCL10 and NF-κB. Number of patients in individual subgroups is indicated at the top of the corresponding histogram.

Correlation between H pylori independence and API2-MALT1 fusion transcript and nuclear expression of BCL10 and NF-κB. Number of patients in individual subgroups is indicated at the top of the corresponding histogram.

Correlation of nuclear expression of BCL10 and NF-κB with tumor response to H pylori eradication in all patients with low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma

As a single variable, the frequency of nuclear expression of BCL10 was significantly higher in H pylori–independent than in H pylori–dependent tumors (20 of 23 [86.9%] vs 3 of 37 [8.1%]; P < .001). The frequency of nuclear expression of NF-κB was also significantly higher in H pylori–independent than in H pylori–dependent tumors (19 of 23 [82.6%] vs 3 of 37 [8.1%]; P < .001). The sensitivity in predicting H pylori independence of low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas was 86.9% for nuclear expression of BCL10 and 82.6% for nuclear expression of NF-κB. The specificity in predicting H pylori independence of low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas was 91.9% for nuclear expression of either BCL10 or NF-κB (Table 1; Figure 4).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that nuclear expression of BCL10 and nuclear expression of NF-κB are 2 highly useful markers for predicting the H pylori–independent status of low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas with or without t(11;18)(q21;q21).

t(11;18)(q21;21) results in the expression of a chimeric protein with the amino terminal of the API2 fusing the carboxyl terminal MALT125 and is closely associated with the H pylori–independent state of low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma.4,5 In a large retrospective study, t(11;18)(q21;21) was detected in 60% of stage IE H pylori–independent low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas.5 These results are in line with our observation that t(11;18)(q21;21) was found in only half of H pylori–independent, early-stage low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas. For the other half of H pylori–independent tumors, other predictive markers should be pursued.

In our previous studies, we showed that nuclear translocation and coexpression of BCL10 and NF-κB were closely associated with the H pylori–independent status of high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas, which usually lack t(11;18)(q21;q21).19 In this study, we extended this finding to include low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma lacking t(11;18)(q21;q21). That a proportion of low-grade MALT lymphomas lacking t(11;18)(q21;q21) express nuclear BCL10 has also been observed by several other groups of investigators, though the relationship with H pylori independence was not described.26,27 BCL10 contains a caspase recruitment domain (CARD) and a C-terminal serine- and threonine-rich domain.7,8 Recent evidence indicates that the up-regulation of B-cell antigen receptor signaling triggers the activation of protein kinase C β and thereby results in the phosphorylation of CARMA1 (also known as CARD11 or BIMP1), leading to BCL10 oligomerization.14,28,29 BCL10 then activates NF-κB by MALT1 and ubiquitin-conjugating, enzyme-dependent IκB kinase ubiquitination.30 As NF-κB is activated, it translocates to the nucleus and results in the production of cytokines and growth factors that are important for cellular activation, proliferation, and survival of B cells.17 In the present study, nuclear expression of NF-κB was closely associated with the aberrant nuclear expression of BCL10 in H pylori–independent low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. This finding is in line with our previous study reporting that nuclear translocation of NF-κB was highly predictive of H pylori–independent status in high-grade gastric MALT lymphoma.19 Additional investigation of the molecular interaction and biologic consequences of nuclear translocation of BCL10 and NF-κB in gastric MALT lymphoma is needed.

Nuclear translocation of BCL10 and NF-κB was observed in all but 1 instance of t(11;18)(q21;q21) in this series, and this exception occurred in a patient who had a rare H pylori–dependent, t(11;18)(q21; q21)–positive tumor. This finding implies that nuclear translocation of BCL10 and NF-κB may even be more specific than t(11;18)(q21;q21) in predicting H pylori independence for gastric MALT lymphoma. Interestingly, the fusion transcript of this patient comprised the amino terminal API2 with 3 intact BIR domains and the carboxy terminal MALT1 region containing an intact caspaselike domain but no immunoglobulinlike domain (data not shown). Indeed, the fusion products with an intact immunoglobulinlike domain have been shown to be more potent activators of NF-κB than those without an immunoglobulinlike domain.16,29 Whether the patterns of fusion transcripts of t(11;18)(q21;q21) may contribute to nuclear translocation of NF-κB or BCL10 and thereby affect H pylori–independent transformation of the tumor remains to be clarified.

This study did not examine other rare genetic aberrations that may relate to nuclear BCL10 expression. However, several recent studies detected t(1;14)(p22;q32) in less than 5% of low-grade MALT lymphomas.9,31 Indeed, 30% to 40% of gastric MALT lymphomas lacking both t(11;18)(q21;q21) and t(1; 14)(p22;q32) showed a moderate degree of nuclear expression of BCL10.31 Moreover, a recent study of 71 patients with gastric MALT lymphoma found that none harbored t(1;14)(p22;32),32 suggesting that the latter genetic aberration is so rare that it may not be useful as a predictor. Because immunohistochemical staining for detection of BCL10 or NF-κB nuclear expression is not only specific and sensitive in predicting H pylori–independent status but also much more feasible for the daily practice of general pathology laboratories, it is an invaluable method to help select the best first-line treatment for patients with low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma.

Scheme of the relationship between H pylori independence and API2-MALT1 fusion transcript and protein expression of BCL10 and NF-κB. n indicates the number of patients in individual subgroups; N, nuclear expression; C, cytoplasmic expression.

Scheme of the relationship between H pylori independence and API2-MALT1 fusion transcript and protein expression of BCL10 and NF-κB. n indicates the number of patients in individual subgroups; N, nuclear expression; C, cytoplasmic expression.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, April 21, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0004.

Supported by research grants NSC91-3112-B-002-009, NSC92-3112-B-002-027, and NSC93-3112-B-002-007 from the National Science Council; NHRI-CN-CA9201S, 92A084, and 93A059 from the National Health Research Institutes; and NTUH 93-N012 and NTUH 94S155 from National Taiwan University Hospital, Taiwan.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal