Comment on Amadori et al, page 27

Treatment failure in older adults with AML is due to leukemia cell drug resistance as well as death due to infection. The EORTC and GIMEMA groups addressed these problems in a randomized trial using growth factors both during and after induction chemotherapy.

Combinations of pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, cellular pharmacologic, cytokinetic, and other factors contribute to treatment failure in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The problem is particularly critical in the large group of older patients with AML in whom complete remission rates are about 50%, with long-term disease-free survival in less than 10% of patients entered on clinical trials. These results have not improved in the past 15+ years and it is likely that results in patients entered on trials are superior to the outcome in the larger universe of older patients with AML, given the selection criteria of performance status and adequate organ function imposed by such trials.

Given the ability to recruit large numbers of patients with hematologic malignancies in Europe (in striking contrast to what is now feasible in the United States), the large study from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) and Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell'Adulto (GIMEMA) groups reported in this issue of Blood employed an ambitious 2×2 factorial randomization, simultaneously addressing the supportive care problem of prolonged neutropenia as well as the more interesting question of recruitment of cytokinetically quiescent leukemia cells by simultaneous administration of growth factors with the chemotherapy. There is substantial in vitro data to support this “priming” approach, which is designed to coax the small but critical subpopulation of leukemia stem cells into cell cycle and then blow them to kingdom come.

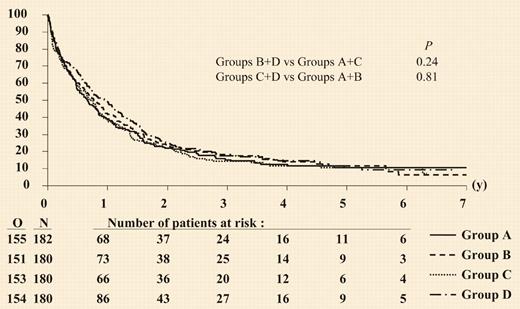

As with other previously published randomized studies,1-4 myeloid growth factors administered after the completion of chemotherapy produced modest shortening of the duration of neutropenia with no effect on complete remission (CR) rates, death during induction, CR duration, or overall survival. Although the CR rate was higher in the pooled results from the 2 groups that received the growth factor as “priming,” this was due almost entirely to the group who received the granulocyte–colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) both during and after the chemotherapy. There was, however, no effect on event-free survival, disease-free survival, or overall survival, and as shown in the figure, the overall results are unfortunately reminiscent of all other trials in older patients with AML.FIG1

Duration of overall survival according to randomized treatment group. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 27.

Duration of overall survival according to randomized treatment group. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 27.

The authors appropriately point out that most studies evaluating CSF priming also produced disappointing results, although there were some differences in study design, patient populations, and the timing and type of growth factors used. I hope that clinicians/statisticians will not succumb to the highly contagious metanalysis virus in an attempt to tease out a modest difference, because such an effort is unlikely to advance our understanding of the mechanism of treatment failure or to advance the treatment of AML.

It is unknown whether the biologic goal of leukemia cell recruitment was actually achieved and whether this might have correlated with response. Indeed, it is not really possible to determine whether the subpopulation of leukemia stem cells was perturbed by the stimulation or whether it continued to lie low, raising its head after the threat of chemotherapy had passed. AML is also a remarkably heterogeneous disease with new molecular markers such as FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT3) mutations and partial duplication of the mixed-lineage leukemia gene (MLL) and increased brain and acute leukemia cytoplasmic gene (BAALC) expression as but some of the changes affecting drug resistance and outcome in ways that are not understood. It may be naive to consider that cytokinetic manipulation will affect these potentially different disorders in the same way.

Significant improvements in outcome with new agents are more likely to derive from focused attacks, once the pathogenesis of different molecular subtypes of leukemia are better elucidated. Given the poor and stagnant outcome in older patients with AML, it is imperative that screening trials with new approaches be done rapidly and efficiently, advancing only the most promising findings to large phase 3 trials, with as little redundancy as possible among these trials. ▪

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal