Comment on Hirakawa et al, page 2392

From Hollywood actors to a family at the beach, seldom has a scientific study held such broad potential implications as those found in a paper by Hirakawa and colleagues. Sunburn and wrinkles have always been considered the obligate consequences of short- and long-term unprotected exposure to the sun and the UVB rays it contains. However, Hirakawa et al have raised a question: are all of the effects of photosensitivity just the necessary consequence of our skin's ability to heal? Or is there something more to these red welts, blisters, and premature aging?

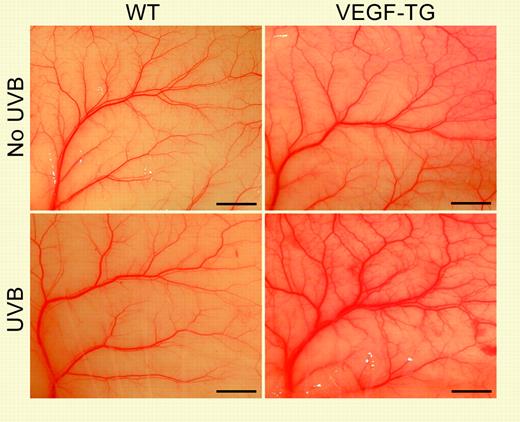

Addition of VEGF expressed from a transgene cassette (VEGF-TG) sensitizes the skin to long-term low-dose UVB exposure. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2392.

Addition of VEGF expressed from a transgene cassette (VEGF-TG) sensitizes the skin to long-term low-dose UVB exposure. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2392.

This study focuses on the roles of the multi-talented vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene in skin photosensitivity. Ultraviolet B (UVB) exposure has been known to induce a proangiogenic epidermal environment by activating several vessel-inducing growth factors (including VEGF) while simultaneously reducing the expression of at least one prominent angiogenic inhibitor. To test whether VEGF specifically contributes to photosensitivity, VEGF protein was added either as expression from a transgenic cassette or through the direct addition of a localized VEGF protein source. In both cases, the animals responded by altering vessel function and development. But when these animals were also exposed to UVB, the addition of VEGF sensitized the skin to the effects of acute photoexposure, yielding a sunburnlike response under conditions where the control animals showed no ill effects. In addition, these same VEGF transgenic animals, when chronically exposed to a low dose of UVB, displayed wrinkles and other effects as observed in photo-induced premature aging of the skin; in contrast, wild-type animals treated in parallel showed no such effect. Could VEGF, this protein critical for a normal wound healing response, instead be contributing to our rather specific and largely detrimental epidermal response upon exposure to UVB?

To specifically test this, Hirakawa and colleagues asked whether the addition of a VEGF antibody could ameliorate skin photosensitivity. Simple injection of this VEGF-inhibiting protein blocked the effects of acute UVB exposure. Of critical note, this effect did not reduce the ability of these animals to undergo post-UVB repair. These 2 parts of the study thus show that VEGF is both necessary and sufficient for photosensitivity of the skin.

What is the mechanism of VEGF-mediated photosensitivity? This is not clear. VEGF is only a part of the endogenous proangiogenic response to UVB. Or perhaps this sensitivity is simply a balance, as in the inflammation process, where precocious activation can be as much a part of clinical symptoms as the exogenous causal agent. The implications go well beyond sunburn: does this UVB-based activation of VEGF and the proangiogenic environment it confers contribute to the increased risk of skin cancer?

Antiangiogenic therapies, many focused on VEGF, are in the pipeline for the treatment of cancer and other ailments where the growth of new vasculature is a key component of the disease. Will topical application of a drug originally designed to treat chronic diseases like metastatic cancer help those of us who have had too much fun in the sun? Stay tuned. ▪

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal