Comment on Solomon, page 978

Measurement of vitamin B12, homocysteine, and methylmalonic acid may not be the ultimate “gold standard” for diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency.

Measurement of the serum vitamin B12 level has been widely used as the standard screening test for cobalamin deficiency. It has, however, long been recognized that because of sensitivity and specificity problems, the test has poor positive and negative clinical predictive value.1,2 In essence, a low serum vitamin B12 level does not always connote cobalamin deficiency, nor does a “normal” serum vitamin B12 level reliably indicate normalcy. Cobalamin is a necessary cofactor for 2 metabolic reactions. In cobalamin deficiency, resulting bottlenecks cause 2 substrates in those reactions, methylmalonic acid and homocysteine, to accumulate. When clinical diagnostic assays to measure these compounds in the serum became available,3 they replaced serum B12 as the “gold standard” for diagnosing cobalamin deficiency. However, some concerns about the use of these assays and the interpretation of their results soon began to emerge4 and some of the gloss began to fade.FIG1

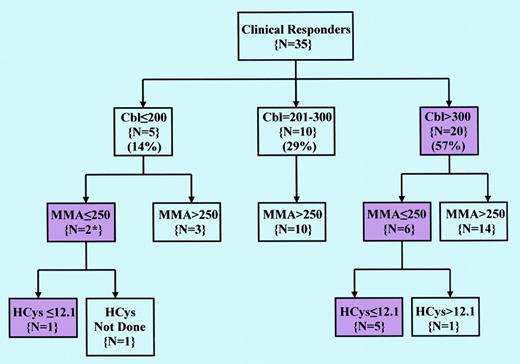

Pattern of Cbl, MMA, and HCys values in patients with clinical responses to Cbl therapy. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 978.

Pattern of Cbl, MMA, and HCys values in patients with clinical responses to Cbl therapy. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 978.

In this issue, Solomon reports the results of a retrospective review of the records of a large group of patients in an ambulatory setting at a staff model HMO over a 10-year period. These patients were evaluated for possible cobalamin deficiency using the standard laboratory tests of serum B12, methylmalonic acid, and homocysteine. The startling and disturbing findings in this study are that all assays showed considerable variability before any treatment was initiated and that the results of these assays taken singly or in combination often did not reliably predict or preclude a response to specific treatment with vitamin B12. Taken at face value and given the general reliance placed on the clinical reliability of these tests for identification of cobalamin deficiency, these findings are extremely troubling. Overdiagnosis of cobalamin deficiency is one thing, carrying with it the negative consequences of possible unnecessary, but essentially innocuous, treatment as well as burdensome cost; missed diagnosis is, quite clearly, a matter of greater gravity, particularly since the risk of formidable devastation from neurologic damage that results from uncorrected cobalamin deficiency is preventable. In 37 of the patients reported by Solomon who responded to pharmacologic doses of vitamin B12, pretreatment values of serum B12 and homocysteine were normal in approximately 1 of every 2 and methylmalonate in 1 of every 4 patients (Figure 1).

Solomon's provocative findings convey an apt and timely caution and may shake up present complacencies. Many have come to accept at face value the glib messages and mantras conveyed by assay kit manufacturers and the enshrined dogmas that permeate the literature that the laboratory identification of clinically significant cobalamin deficiency is a “cake walk.” Indeed, it may be time to carefully reassess a field that is perhaps in a state of confusion and disarray not dissimilar to what existed when radioassays were introduced to replace microbiologic assays for measuring B12. The situation may now be aggravated since the introduction of folic acid fortification of the diet in North America and elsewhere is giving rise to the potential risk of undetected cobalamin deficiency, through “masking” by folate. Moreover, with the virtual disappearance of folate deficiency, cobalamin deficiency has become the most common modifiable cause of hyperhomocysteinemia, with its potential attendant risks of atherothrombosis.

At this stage, it would be prudent to conclude that the currently available assays for identifying or excluding cobalamin deficiency, though potentially useful, should be used with full awareness of their possible limitations, at least until unresolved issues have been settled. Serious questions have been raised about the clinical dependability of the trio of tests variously considered as gold standards for suspicion or confirmation of cobalamin deficiency with a possible devaluation in the currency of all. Nothing gold can stay.5 ▪

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal