Comment on Jordan et al, page 735

Jordan and colleagues present a perforin deficiency–dependent model for virus-induced HLH in mice, highlighting IFN-γ as the only cytokine relevant for major clinical characteristics and mortality in mice.

What would happen in a bullfight if the matador lacked weapons against his self-made outrageous enemy? Since the original clinical description of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) called Morbus Farquhar,1 it has become obvious that hyperinflammation is not guided by T-H1/T-H2 counterregulation.2,3 Today, 3 laboratory findings are clearly associated with HLH. First is a long list of inflammatory as well as anti-inflammatory cytokines, none of which has been unequivocally shown to either initiate or expand systemic hyperinflammation in vivo. Second is hemophagocytosis by macrophages, leading to cytopenia and a high incidence of infections and secondary inflammatory illness. Third, functional and genetic studies have proven that natural killer (NK) deficiency by mutated perforin or Munc13-4 predispose for the manifestations of familial HLH.4,5

In an animal model that combines familial and secondary HLH, Jordan and colleagues infected perforin-deficient C57Bl/6 mice with a prevalence of CD8+ lymphocytes with a virus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus strain WE (LCMV-WE), and successfully induced hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis presenting with a complete pattern of clinical and laboratory features in human disease. This animal model focuses our view of essential mediators to interferon-γ (IFN-γ). Unlimited IFN-γ production in these virus-infected mice caused massive phagocytosis, concomitant anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia, as well as the quantifiable infiltration of vital organs with macrophages. Moreover, IFN-γ and CD8+ lymphocytes are the common denominators to cause rapid death in these mice by day 12 following infection; by neutralizing LCMV antibodies (Jordan and colleagues [Figure 6F]), blocking IFN-γ (Jordan and colleagues [Figure 4B]), and depleting of CD8+ cells (Jordan and colleagues [Figure 4A]), survival can be improved. However, blocking of other cytokines, including IL-12 and IFN-α, or depletion of CD4 or NK1.1 had no effect. Recombinase activating gene (RAG) deficiency did not lead to HLH following LCMV-WE infection, but RAG/perforin double deficiency prevented the manifestation of HLH.FIG1

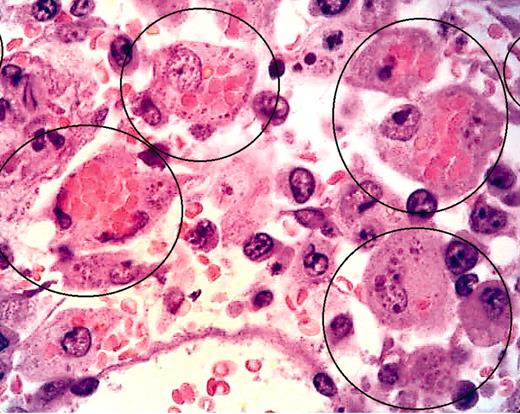

LCMV-infected pfp–/– mice display histopathologic features of HLH. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 735.

LCMV-infected pfp–/– mice display histopathologic features of HLH. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 735.

Importantly, these observations open novel therapeutic tools to treat human HLH in addition to the current immunosuppressive regimen using corticosteroids, cyclosporin A, and the apoptosis-inducing drug etoposide. Results presented in the mouse model support the view that perforin-mutated mice are devoid of any down-regulative effects that are present in wild-type mice treated by chronic antigenic stimulation, since granule-dependent cellular cytotoxicity is essential for controlling hyperactivated antigen-presenting cells (Jordan and colleagues [Figure 7]).

The current model mirrors the fatal course in a bullfight using consecutive paintings by Pablo Picasso originating in 1959, some years later than the original description of hemophagocytic syndromes in families by Farquhar and Claireaux.1 In this analogous scenario, infections may sensitize and weaken macrophages like picadors (as the subordinators of the matador) do when they lance the bull (toro) in the back of his neck during the first section of the fight (faena). Then, the excitement of the crowd in the arena and the matador presenting his strength to the bull, with its head dropped to the level of the bullfighter, are comparable with high amounts of interferon released by NK and T cells to maximally activate the macrophage. In the second section of the faena, so-called banderillas, barbed colored sticks, are stabbed into the bull's neck to maintain its state of fury and aggression. From the results presented, the molecular equivalents of such banderillas that perpetuate macrophage activation are not yet defined but have to be postulated. In a bullfight, the matador kills the toro, after exchanging the long straight sword he uses to position his cape for a smaller one with a curved end that he hides behind his cape. So far we do not know for sure whether perforin is the hidden weapon that wild-type animals use to control hemophagocytosis by macrophages/dendritic cells. The hidden sword may well be a molecule counterregulating IFN-γ, since IL-10 can already be ruled out as a candidate.6 In a more general context of inflammatory diseases, including sepsis and septic shock associated with acquired NK deficiency, this animal model will be of exemplary value.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal