Abstract

Proteins secreted by activated platelets can adhere to the vessel wall and promote the development of atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Despite this biologic significance, however, the complement of proteins comprising the platelet releasate is largely unknown. Using a proteomics approach, we have identified more than 300 proteins released by human platelets following thrombin activation. Many of the proteins identified were not previously attributed to platelets, including secretogranin III, a potential monocyte chemoattractant precursor; cyclophilin A, a vascular smooth muscle cell growth factor; calumenin, an inhibitor of the vitamin K epoxide reductase-warfarin interaction, as well as proteins of unknown function that map to expressed sequence tags. Secretogranin III, cyclophilin A, and calumenin were confirmed to localize in platelets and to be released upon activation. Furthermore, while absent in normal vasculature, they were identified in human atherosclerotic lesions. Therefore, these and other proteins released from platelets may contribute to atherosclerosis and to the thrombosis that complicates the disease. Moreover, as soluble extracellular proteins, they may prove suitable as novel therapeutic targets.

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease influenced by circulating cells, including platelets.1 Endothelial dysfunction, an early event in this process, leads to platelet adhesion, which in turn leads to several steps in the development of atherosclerosis, including leukocyte infiltration.2 Furthermore, inhibition of platelet adhesion reduces leukocyte accumulation and attenuates the progression of atherosclerotic lesions in the cholesterol-fed apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE–/–) mouse.3 Platelets may mediate such effects through products released following adhesion and activation. Indeed, platelet-derived chemokines such as platelet factor 4 (PF4) are found in atherosclerotic plaques where they express biologic activities that may contribute to several aspects of the disease.3,4

Platelets contain a number of preformed, morphologically distinguishable storage granules—α-granules, dense granules, and lysosomes—the contents of which are released upon platelet activation.5 Platelets also release 2 distinct membrane vesicle populations during activation: cell surface–derived microvesicles and exosomes of endosomal origin.6 Microvesicles have a protein content similar to the activated plasma membrane and have procoagulant and inflammatory functions.7 On the other hand, exosomes are released following fusion of subclasses of α-granules and multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and their function remains unknown.6 Exosomes are secreted by a multitude of other cells including those of hematopoietic lineage, such as cytotoxic T cells,8 antigen-presenting B cells,9 and dendritic cells,10 where they play an immunoregulatory role.11 Proteomic analysis of exosomes secreted from various cell types has revealed the presence of ubiquitous proteins such as tubulin, actin, and actin-binding proteins, as well as cell type–specific proteins.12,13

Secreted platelet proteins act in an autocrine or paracrine fashion to modulate cell signaling. Several of the proteins (eg, growth arrest specific gene 6 [GAS-6], factor V) are prothrombotic, whereas others (eg, platelet-derived growth factor [PDGF]), regulate cell proliferation.14 Platelets also release several immune modulators such as platelet basic protein whose proteolytic product is neutrophil-activating peptide 2 (NAP-2),15 in addition to adhesion proteins such as platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) that may support leukocyte migration.16 Thus, the platelet releasate contains factors of major significance in the development of atherothrombosis. Here, we used a comprehensive proteomics approach to isolate, separate, and identify the contents of the platelet releasate, a fraction highly enriched for platelet granular and exosomal contents, and we demonstrate the presence of several of these proteins in human atherosclerotic lesions.

Patients, materials, and methods

Platelet aggregation and isolation of supernatant fraction

Washed platelets were prepared and aggregations performed with 0.5 U/mL thrombin, as previously described.17 Following aggregation, platelets were removed by centrifuging sequentially twice at 1000g for 10 minutes and harvesting the supernatant. The supernatant was further subjected to ultracentrifugation for 1 hour at 4°C at 50000gmax using a 50.4 Ti rotor (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA) to remove microvesicles. The purity of the releasate fraction was confirmed by the absence of platelet membrane–specific protein αIIb and the signaling protein focal adhesion kinase (FAK; results not shown).

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

The methods for sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting were as previously described.17 Protein concentration was measured according to Bradford, and the same amount of protein (40 μg) loaded onto each well. For total platelet lysate this was equivalent to about 1.5 × 107 platelets and for releasate about 8 × 108 platelets. The primary monoclonal antibody to thrombospondin clone p10 (1:1000 dilution) and polyclonal antigoat (C-19) antibody to secretogranin III were purchased from Chemicon International (Hampshire, United Kingdom) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Heidelberg, Germany), respectively. The polyclonal antirabbit antibody to calumenin was a kind gift from Dr Reidar Wallin (Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC). The polyclonal antirabbit antibody against cyclophilin A was from Upstate Biotechnology (Milton Keynes, United Kingdom). Antimouse, antigoat, and antirabbit secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP) antibodies were obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Fluorescence was detected using West Pico Supersignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce).

Two-dimensional electrophoresis

Two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE) was performed as previously delineated,17 with the following minor modifications. A total of 400 μg released protein (∼ 8 × 109 platelets) was focused for 100 000 volt hours (Vh) on 18-cm, pI 3-10 immobiline dry strips using the Multiphor Isoelectric Focusing Unit (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) and then sealed on top of 10% polyacrylamide gels (20 × 20 cm). Protein spots were visualized using a G-250 colloidal Coomassie blue dye (Sigma, Dublin, Ireland).

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

In-gel digestion and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) was carried out as earlier outlined.17,18 Spectra were analyzed by searching with the publicly available search algorithm Mascot (http://www.matrixscience.com/cgi/search_form.pl?FORMVER=2&SEARCH=PMF) using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and SwissProt databases.19

Multidimensional protein identification technology and liquid chromatography-ion trap MS

Approximately 300 μg protein (∼ 6 × 109 platelets) was precipitated overnight with 5 volumes of ice-cold acetone followed by centrifugation at 21 000g for 20 minutes. The pellet was solubilized in 8 M urea, 50 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane)–HCl, pH 8.5, at 37°C for 2 hours and reduced by addition of 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by carboxyamidomethylation with 5 mM iodoacetamide for 1 hour at 37°C. The samples were diluted to 4 M urea with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.5, and digested with a 1:150 molar ratio of endoproteinase Lys-C at 37°C overnight. The next day, the mixtures were further diluted to 2 M urea with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.5, supplemented with calcium chloride to a final concentration of 1 mM, and incubated overnight with Poroszyme-immobilized trypsin beads at 30°C with rotating. The resulting peptide mixtures were solid-phase extracted with SPEC-Plus PT C18 cartridges (Ansys Diagnostics; Lake Forest, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions and stored at –80°C until further use.

A fully automated 7-cycle, 14-hour multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT) chromatographic procedure was set up essentially as described.20,21 Briefly, a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) quaternary pump was interfaced with an LCQ DECA XP ion trap tandem mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan, San Jose, CA). A 150-μm internal diameter fused silica capillary microcolumn (Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ) was pulled to a fine tip using a P-2000 laser puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and packed with 10-cm of 5-μm Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 resin (Agilent Technologies, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and then with 6 cm of 5-μm Partisphere strong cation exchange resin (Whatman, Clifton, NJ). Samples were loaded manually onto separate columns using a pressure vessel and chromatography was performed as described.22 The SEQUEST algorithm was used to identify proteins from tandem mass spectra.23 The ion state, XCorr, and DCn criteria to yield less than 1% false-positive identification were used.24

Affymetrix RNA analysis

Total RNA was isolated from highly purified platelet preparations, pooled, and hybridized to the Affymetrix HG-U95Av2 array, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Only samples that were positive by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for platelet-specific proteins (GPIIb, GPIIIa and the low abundance CD151) and were negative for white cell markers (CD53 and δ chain of the T-cell antigen receptor–associated T3 complex) were pooled for analysis. Average difference values were scaled and transformed in accordance with the Gene Expression Atlas (http://expression.gnf.org/cgibin/index.cgi).25 For comparison to proteomic data, Affymetrix probe sets were mapped to UniGene clusters (build 157, November 2002).

Confocal microscopy

Glass slides were coated with 20 μg/mL fibrinogen in buffer A (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) at 37°C for 2 hours and subsequently blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 hour. The platelets were resuspended in a modified Tyrode buffer (130 mM NaCl, 10 mM trisodium citrate, 9 mM NaHCO3, 6 mM dextrose, 0.9 mM MgCl2, 0.81 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4) at a concentration of 20 to 30 × 105/μL and allowed to adhere to the blocked slides for the indicated time, prior to fixation for 7 minutes in ice-cold methanol. Slides were then permeabilized in ice-cold acetone for 2 minutes and blocked with normal goat serum or BSA at room temperature for 30 minutes. The slides were incubated with primary antibody (antibodies as for Western blotting) for 45 minutes and then a fluorescent secondary antibody (Alexa 488–conjugated goat antirabbit or mouse antigoat) for 10 minutes. These slides were visualized using an argon laser at 488 nm. For dual-stained images, the slides were incubated with anti-CD41 monoclonal antibody (IgG1; clone SZ22; Beckman Coulter, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) for an additional 45 minutes and then a fluorescent Alexa 546–conjugated goat antimouse secondary for 10 minutes. Control procedures included unstained cells to allow for autofluorescence, secondary antibody only, and primary antibodies with 2 differentially labeled secondaries to check for nonspecific fluorescence. All images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 510 Confocal Microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry

Samples of arterial tissue were obtained from patients with atherosclerosis at the time of surgery for carotid or peripheral vascular disease (n = 5) and fixed in formal saline for immunohistochemistry analysis.26 The study was approved by the Irish Medicines Board and the Ethics Committee of Beaumont Hospital, Dublin, and all patients gave written informed consent. All patients were undergoing surgical revascularization for peripheral vascular disease or carotid endarterectomy. Normal arterial sections were obtained from young individuals who had no gross or microscopic evidence of atherosclerosis. Sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and for proteins of interest, as described previously.26 Primary antibodies were as for Western blotting and confocal microscopy. Antirabbit PF4 polyclonal antibody (Ab1488P) was from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). Monoclonal anti-α smooth muscle actin (mouse IgG2a isotype) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Tallaght, Ireland).26

Results

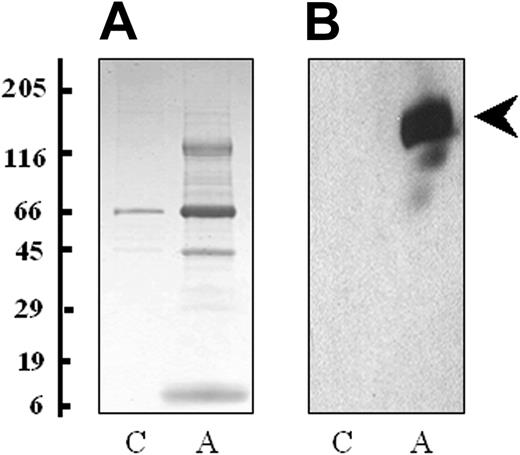

Platelets were isolated by differential centrifugation and stimulated with 0.5 U/mL thrombin for 3 minutes to achieve maximum release of all granule contents (α, dense, and lysosomal).27 It is expected that the secretion profile of platelets would change depending on the agonist, although this may be more quantitative than qualitative. To visualize the proteins released from thrombin-activated platelets, the releasate fraction was harvested by centrifugation and separated using one-dimensional SDS-PAGE. A considerably higher concentration of protein was found in the thrombin-activated sample, particularly between the molecular weights of 5 and 15 kDa, 30 and 50 kDa, and 120 and 180 kDa (Figure 1A). Western blot analysis demonstrated thrombospondin (p10), a known secreted protein, only in the activated releasate lane (Figure 1B). Flow cytometry for P-selectin (CD62), an α-granule marker protein, showed a 3-fold increase in platelet expression following treatment with thrombin, indicative of α-granule membrane fusion and exocytosis. Western blotting for the signaling protein FAK and the membrane protein αIIb were performed on platelet lysates and platelet supernatant fractions. These proteins were not found in the platelet supernatant fractions indicating that platelet cell lysis had not occurred and microvesicles were not present in the preparation (data not shown).

Proteins released by platelets following thrombin activation. (A) The proteins from the supernatant of nonactivated (C) and thrombin-activated platelets (A) were solubilized in SDS reducing buffer, separated by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE (4%-20% gradient gel) and stained with colloidal Coomassie blue. (B) A duplicate of the gel was probed with a monoclonal antibody to thrombospondin (clone p10). Molecular weight markers are indicated.

Proteins released by platelets following thrombin activation. (A) The proteins from the supernatant of nonactivated (C) and thrombin-activated platelets (A) were solubilized in SDS reducing buffer, separated by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE (4%-20% gradient gel) and stained with colloidal Coomassie blue. (B) A duplicate of the gel was probed with a monoclonal antibody to thrombospondin (clone p10). Molecular weight markers are indicated.

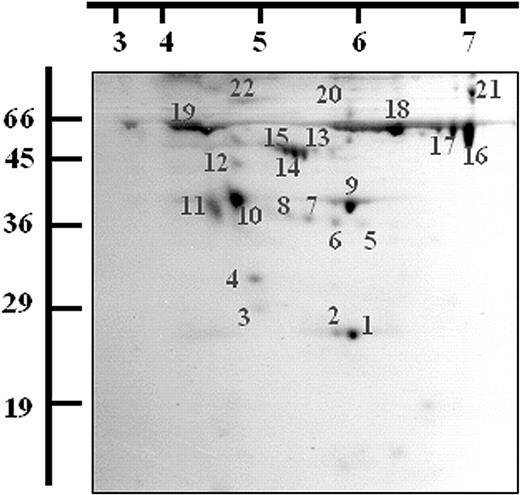

Twenty-two protein spots were excised and digested with trypsin following 2-dimensional (2-D) gel electrophoresis of the activated platelet releasate and staining with Coomassie blue. The resulting peptides were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS and the proteins identified using Mascot. The identifications were accepted if they represented the highest-ranking hit, had MOWSE scores over 64, and if the sequence coverage was at least 15% to 30% (depending on protein size).28 The protein identities, sequence coverage, and MOWSE probability scores obtained for the each of the 22 spots are detailed in Table 1 and Figure 2. Nine different proteins were identified from the 22 spots, several being isomeric forms of the same protein (Figure 2).

Proteins released from thrombin-activated platelets identified by MALDI-TOF MS

Spot no. . | Protein identity . | Accession no. . | Molecular weight, Mr . | Isoelectric point, pl . | Sequence coverage, % . | MOWSE score . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Apo A1 fragment | CAA00975 | 28 061 | 5.27 | 59 | 232 |

| 2 | Apo A1 fragment | CAA00975 | 28 061 | 5.27 | 46 | 125 |

| 3 | 14-3-3 protein ζ/δ | 1QIBA | 26 297 | 4.99 | 38 | 116 |

| 4 | TMP4-ALK fusion oncoprotein type 2 | Q9HBZ0 | 27 570 | 4.77 | 29 | 102 |

| 5 | Haptoglobin | AAC27432 | 38 722 | 6.14 | 25 | 91 |

| 6 | Haptoglobin | AAC27432 | 38 722 | 6.14 | 36 | 151 |

| 7 | Haptoglobin | AAC27432 | 38 722 | 6.14 | 30 | 137 |

| 8 | Haptoglobin | AAC27432 | 38 722 | 6.14 | 36 | 140 |

| 9 | Actin | CAA27396 | 39 446 | 5.78 | 54 | 158 |

| 10 | Osteonectin | O08953 | 35 129 | 4.81 | 37 | 127 |

| 11 | Osteonectin | O08953 | 35 129 | 4.81 | 37 | 119 |

| 12 | Thrombospondin | CAA32889 | 133 261 | 4.71 | 15 | 111 |

| 13 | α1-antitrypsin | CAA00206 | 44 291 | 5.36 | 21 | 120 |

| 14 | αj-antitrypsin | CAA00206 | 44 291 | 5.36 | 21 | 109 |

| 15 | α1-antitrypsin | CAA00206 | 44 291 | 5.36 | 21 | 120 |

| 16 | Serum albumin | CAA00298 | 68 588 | 5.67 | 30 | 194 |

| 17 | Serum albumin | 1AO6A | 676 090 | 5.63 | 27 | 161 |

| 18 | Serum albumin | CAA00298 | 68 588 | 5.67 | 27 | 159 |

| 19 | Albumin | CAA01216 | 68 425 | 5.67 | 29 | 154 |

| 20 | Serum albumin | 1AO6A | 67 690 | 5.63 | 25 | 164 |

| 21 | Serum albumin | 1AO6A | 67 690 | 5.63 | 17 | 90 |

| 22 | Albumin | AA64922 | 53 416 | 5.69 | 33 | 150 |

Spot no. . | Protein identity . | Accession no. . | Molecular weight, Mr . | Isoelectric point, pl . | Sequence coverage, % . | MOWSE score . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Apo A1 fragment | CAA00975 | 28 061 | 5.27 | 59 | 232 |

| 2 | Apo A1 fragment | CAA00975 | 28 061 | 5.27 | 46 | 125 |

| 3 | 14-3-3 protein ζ/δ | 1QIBA | 26 297 | 4.99 | 38 | 116 |

| 4 | TMP4-ALK fusion oncoprotein type 2 | Q9HBZ0 | 27 570 | 4.77 | 29 | 102 |

| 5 | Haptoglobin | AAC27432 | 38 722 | 6.14 | 25 | 91 |

| 6 | Haptoglobin | AAC27432 | 38 722 | 6.14 | 36 | 151 |

| 7 | Haptoglobin | AAC27432 | 38 722 | 6.14 | 30 | 137 |

| 8 | Haptoglobin | AAC27432 | 38 722 | 6.14 | 36 | 140 |

| 9 | Actin | CAA27396 | 39 446 | 5.78 | 54 | 158 |

| 10 | Osteonectin | O08953 | 35 129 | 4.81 | 37 | 127 |

| 11 | Osteonectin | O08953 | 35 129 | 4.81 | 37 | 119 |

| 12 | Thrombospondin | CAA32889 | 133 261 | 4.71 | 15 | 111 |

| 13 | α1-antitrypsin | CAA00206 | 44 291 | 5.36 | 21 | 120 |

| 14 | αj-antitrypsin | CAA00206 | 44 291 | 5.36 | 21 | 109 |

| 15 | α1-antitrypsin | CAA00206 | 44 291 | 5.36 | 21 | 120 |

| 16 | Serum albumin | CAA00298 | 68 588 | 5.67 | 30 | 194 |

| 17 | Serum albumin | 1AO6A | 676 090 | 5.63 | 27 | 161 |

| 18 | Serum albumin | CAA00298 | 68 588 | 5.67 | 27 | 159 |

| 19 | Albumin | CAA01216 | 68 425 | 5.67 | 29 | 154 |

| 20 | Serum albumin | 1AO6A | 67 690 | 5.63 | 25 | 164 |

| 21 | Serum albumin | 1AO6A | 67 690 | 5.63 | 17 | 90 |

| 22 | Albumin | AA64922 | 53 416 | 5.69 | 33 | 150 |

Protein identifications were generated from the MASCOT database. The validity of the matches was quantified using MOWSE probability score. The percentage of the protein sequence matched by the generated peptides (the sequence coverage) was also documented.

Two-dimensional electrophoresis of the releasate fraction from thrombin-activated platelets. A total of 400μg of the releasate fraction from thrombin-activated platelets was separated by 2-DE and stained with Coomassie blue dye. Spots were excised and digested with trypsin and the resulting peptides were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. A representative gel is shown and the proteins identified are listed (see Table 1). Molecular weight markers and pI values are indicated.

Two-dimensional electrophoresis of the releasate fraction from thrombin-activated platelets. A total of 400μg of the releasate fraction from thrombin-activated platelets was separated by 2-DE and stained with Coomassie blue dye. Spots were excised and digested with trypsin and the resulting peptides were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. A representative gel is shown and the proteins identified are listed (see Table 1). Molecular weight markers and pI values are indicated.

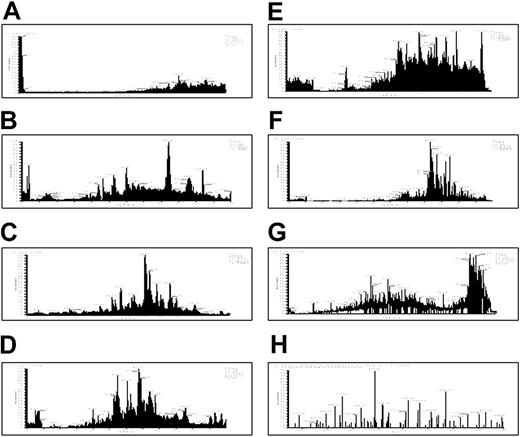

We then used multidimensional liquid chromatography (LC) coupled with electrospray MS to further characterize the platelet releasate. The released protein fraction from thrombin-activated platelets was digested with trypsin and the resulting peptides loaded under pressure onto a nanocapillary column containing both strong cation exchange and reverse-phase materials.29 Seven successive salt elutions and HPLC cycles were used to separate the peptides (Figure 3A-G). The thrombin-activated releasates of pooled donors were analyzed using identical cycle conditions in 3 independent experiments. More than 300 proteins were identified, with 81 observed in 2 or 3 experiments (Table 2). Seventy percent of these 81 were identified in all 3 experiments. Reproducibility of identification for a repeat analysis of a single sample was about 80%. This suggests that about 20% of the variation in the results arises from missed identifications due to saturation of the MudPIT analysis, whereas about 10% may represent donor-to-donor variation.

Seven-step MudPIT. (A-G) The releasate from thrombin-activated platelets was digested with trypsin and the resulting peptides were separated using strong cation exchange and reverse-phase chromatography before introduction into an ion trap mass spectrometer. This figure displays the resulting chromatograms from the 2-dimensional-LC tandem MS. Chromatograms in panels A to G represent 7 successive salt elutions from an HPLC column. (H) A representative tandem MS spectrum is shown for a peptide from thrombospondin that was identified using SEQUEST.

Seven-step MudPIT. (A-G) The releasate from thrombin-activated platelets was digested with trypsin and the resulting peptides were separated using strong cation exchange and reverse-phase chromatography before introduction into an ion trap mass spectrometer. This figure displays the resulting chromatograms from the 2-dimensional-LC tandem MS. Chromatograms in panels A to G represent 7 successive salt elutions from an HPLC column. (H) A representative tandem MS spectrum is shown for a peptide from thrombospondin that was identified using SEQUEST.

Summary of 81 proteins from the thrombin-activated platelet releasate identified using MudPIT

Name . | Accession no. . | Known platelet protein . | Known to be released/exocytosed . | Function . | mRNA rank in platelets . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROTEINS IN THE PLATELET RELEASATE KNOWN TO BE RELEASED FROM PLATELETS | ||||||||||

| Thrombospondin 1 | TSP1_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | On secretion, can bind αIIbβ3, αvβ3, and GPIV. Can potentiate aggregation by complexing with fibrinogen and becoming incorporated into fibrin clots. | 213 | |||||

| Fibrinogen α chain | FIBA_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Cofactor in platelet aggregation. Endocytosed into platelets from plasma. | 632 | |||||

| Fibrinogen γ chain | FIBG_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Cofactor in platelet aggregation. Endocytosed into platelets from plasma. | — | |||||

| Platelet basic protein | SZ07_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Proteolytic cleavage yields the chemokines β-thromboglobulin and neutophil-activating peptide (NAP) 2. | 23 | |||||

| PF4 | PLF4_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Platelet-specific chemokine with neutrophil-activating properties. | 8 | |||||

| Serum albumin | ALBU_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Major plasma protein secreted from the liver into the blood. Endocytosed into platelets from plasma. | — | |||||

| Endothelial cell multimerin | ECM_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Carrier protein for platelet factor V/Vα. | — | |||||

| SPARC (osteonectin) | SPRC_MOUSE | Yes | From platelet α-granules | On secretion, forms a specific complex with thrombospondin. | 14 | |||||

| α-actinin I | AAC1_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Actin-binding and actinin cross-linking protein found in platelet α-granules. Interacts with thrombospondin on the platelet surface. | 171 | |||||

| α1-antitrypsin | A1AT_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Acute phase protein, similar to complement, inhibits proteinases. | — | |||||

| Fibrinogen β chain | FIBB_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Cofactor in platelet aggregation. Endocytosed into platelets from plasma. | — | |||||

| Factor V | FA5_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Cofactor that participates with factor Xa to activate prothrombin to thrombin. | — | |||||

| Secretory granule proteoglycan core protein | PGSG_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Function unknown. Associates and coreleased with inflammatory mediators such as PF4. | 343 | |||||

| Thymosin β-4 | TYB4_MOUSE | Yes | From platelets α-granules | G actin—binding protein. Functions as an antimicrobial peptide when secreted. | 5 | |||||

| Fructose biphosphate aldolase | ALFA_MOUSE | Yes | From platelets and exosomes from dendritic cells | Glycolytic enzymes that convert fructose 1,6-bis phosphate to glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate and dihydroxy acetone phosphate. | 79 | |||||

| Clusterin | CLUS_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Not clear. Possibly platelet-derived apolipoprotein J participates in short-term wound repair and chronic pathogenic processes at vascular interface. | 1 | |||||

| Coagulation factor XIIIA chain | F13A_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Coagulation protein involved in the formation of the fibrin clots. | 19 | |||||

| Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 | TIM1_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Interacts with metalloproteinases and inactivates them. Stimulates growth and differentiation of erythroid progenitors, dependent on disulfide bonds. | 112 | |||||

| Platelet glycoprotein V | GPV_HUMAN | Yes | Cleaved from platelet surface | Part of the GPIb-IX-V complex on the platelet surface. Cleaved by the protease thrombin during thrombin-induced platelet activation. | — | |||||

| von Willebrand factor | VWF_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Binds GPIb-IX-V. | 2465 | |||||

| Amyloid β-A4 protein (protease nexin II | A4_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Exhibits potent protease inhibitor and growth factor activity. May play a role in coagulation by inhibiting factors XIa and IXa. | 379 | |||||

| Latent transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-binding protein isoform 1S | LTBS_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Subunit of the TGF-β1 complex secreted from platelets. | — | |||||

| α-Actinin 2 | AAC2_MOUSE | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Actin-binding and actinin cross-linking protein found in platelet α-granules. Interacts with thrombospondin on the platelet surface. | — | |||||

| Latent TGF-β—binding protein 1L | O88349 | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Subunit of the TGF-β1 complex secreted from platelets. | 617 | |||||

| Proactivator polypeptide | SAP_HUMAN | Yes | From lysosomes | Activator proteins for sphingolipid hydrolases (saposins) that stimulate the hydrolysis of sphingolipids by lysosomal enzymes. | 147 | |||||

| Platelet glycoprotein 1b α chain | GPBA_HUMAN | Yes | Cleaved from platelet surface (glycocalicin) | Surface membrane protein of platelets that participates in formation of platelet plug by binding A1 domain of von Willebrand factor. | 26 | |||||

| Vitamin K—dependent protein S | PRTS_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Cofactor to protein C in the degradation of coagulation factors Va and VIIIA. | 1810 | |||||

| PF4 variant | PF4V_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Platelet-specific chemokines with neutrophil-activating properties. | 346 | |||||

| α2-macroglobulin | A2MG_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Acute phase protein, similar to compliment, inhibits proteinases. | * | |||||

| α-actinin 4 | AAC4_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Actin-binding and actinin cross-linking protein found in platelet α-granules. Interacts with thrombospondin on the platelet surface. | 467 | |||||

| SECRETORY PROTEINS IN THE PLATELET RELEASATE NOT PREVIOUSLY IDENTIFIED IN PLATELETS | ||||||||||

| Vitamin D—binding protein | VTDB-HUMAN | No | From liver to plasma | Carries vitamin D sterols. Prevents actin polymerization. Has Tlymphocyte surface association. | — | |||||

| β2-microglobulin | B2MG_HUMAN | No | Exosomes from dendritic cells, B cells, enterocytes, tumor cells, and T cells | Is the β chain of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecule. | 3 | |||||

| Hemoglobin α chain | HBA_HUMAN | No | Exosomes from dendritic cells and phagosomes in macrophages | Oxygen transport. Potentiates platelet aggregation through thromboxane receptor. | 21 | |||||

| Plasminogen | PLMN_HUMAN | Yes | From kidney into plasma | Dissolves fibrin in blood clots, proteolytic factor in tissue remodeling, tumor invasion, and inflammation. | — | |||||

| Serotransferrin | TRFE_HUMAN | Yes | From liver into plasma | Precursor to macromolecular activators of phagocytosis (MAPP), which enhance leukocyte phagocytosis via the FcγRII receptor. | — | |||||

| Pyruvate kinase, M2 isozyme | KPY2_MOUSE | Yes | B-cell exosomes | Involved in final stage of glycolysis. Presented as an autoantigen by dendritic cells. | 61 | |||||

| Actin, aortic smooth muscle | ACTA_HUMAN | Yes | Exosomes from B cells, dendritic cells, enterocytes, and mastocytes | Major cytoskeletal protein. | — | |||||

| Actin | ACTB_HUMAN | Yes | Exosomes from B cells, dendritic cells, enterocytes, and mastocytes | Major cytoskeletal protein. External function unknown. | 11 | |||||

| 14-3-3 protein ζ/δ | 143Z_MOUSE | Yes | Exosomes from dendritic cells and phagosomes in macrophages | External function unknown. Involved intracellularly in signal transduction, however, may have a role in regulating exocytosis. | 63 | |||||

| Hemopexin | HEMO_HUMAN | No | From liver to plasma | Haem-binding protein with metalloproteinase domains. | — | |||||

| Hemoglobin β chain | HBB_HUMAN | No | From liver to plasma and phagosomes from macrophages | Oxygen transport. | 9 | |||||

| Peptidyl-prolyl-cis isomerase A (cyclophilin A) | CYPH_MOUSE | No | From smooth muscle cells | Cellular protein with isomerase activity. Secreted vascular smooth muscle cell growth factor. | 116 | |||||

| Calumenin | CALU_MOUSE | No | From many cells, including fibroblast and COS cells | An inhibitor of the vitamin K epoxide reductase-warfarin interaction. | 1816 | |||||

| Adenylyl cyclase—associated protein 1 (CAP 1) | CAP1_MOUSE | No | Phagosomes from macrophages | Contains a WH2 actin-binding domain (as β-thymosin 4). Known to regulate actin dynamics. May mediate endocytosis. | 174 | |||||

| Tubulin | TBA1_HUMAN | Yes | Exosomes from dendritic cells and phagosomes from macrophages | Cytoskeletal protein involved in microtubule formation. | 33 | |||||

| Apolipoprotein A-1 | APA1_HUMAN | Yes | From liver to plasma, from monocytes and exosomes of dendritic cells | Role in high-density lipoprotein binding to platelets. | — | |||||

| Compliment C3 | CO3_HUMAN | No | From liver cells and monocytes | Activator of the compliment system. Cleaved to α, β, and γ chains normally prior to secretion and is a mediator of the local inflammatory response. | * | |||||

| Transthyretin | TTHY_HUMAN | No | From choroid plexus into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) | Thyroid hormone—binding protein secreted from the choroid plexus and the liver into CSF and plasma, respectively. | — | |||||

| Cofilin | COF1_MOUSE | Yes | Exosome from dendritic cells | Actin demolymerization/regulation in cytoplasm. | 31 | |||||

| Profilin | PRO1_MOUSE | Yes | Exosome from dendritic cells | Actin demolymerization/regulation in cytoplasm. | 70 | |||||

| Secretogranin III | SG3_MOUSE | No | From neuronal cells | Unclear; possibly involved in secretory granule biogenesis. May be cleaved into active inflammatory peptide like secretogranin II. | * | |||||

| Phosphoglycerate kinase | PGK1_MOUSE | Yes | From tumor cells | Glycotic enzyme. Secreted from tumor cells and involved in angiogenesis. | 378 | |||||

| α-IB glycoprotein | AIBG_HUMAN | No | From many cell including white blood cells | Found in plasma, not clear, possibly involved in cell recognition as a new member of the immunoglobulin family. | * | |||||

| Compliment C4 precursor | CO4_HUMAN | No | From many cells including white blood cells | Activator of the compliment system. Cleaved normally prior to secretion, its products mediate the local inflammatory response. | — | |||||

| Prothrombin | THRB_HUMAN | No | From liver to plasma | Converts fibrinogen to fibrin and activates coagulation factors including factor V. | 2143 | |||||

| Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | G3P2_HUMAN | Yes | From B-cell exosomes and phagosomes from macrophages | Mitochondrial enzyme involved in glycolysis. May catalyze membrane fusion. | 60 | |||||

| α1-acid glycoprotein | A1AH_HUMAN | No | From liver to plasma | Modulates activity of the immune system during the acute phase reaction. Binds platelet surface. | — | |||||

| Gelsolin | GELS_HUMAN | Yes | Secreted isoform released from liver and adipocytes | Two isoforms, a cytoplasmic actin modulating protein and a secreted isoform involved in the inflammatory response. | 438 | |||||

| PROTEINS IN THE PLATELET RELEASATE NOT PREVIOUSLY REPORTED TO BE RELEASED FROM ANY CELL | ||||||||||

| Calmodulin | CALM_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Known to regulate calcium-dependent acrosomal exocytosis in neuroendocrine cells. | 55 | |||||

| Pleckstrin | PLEK_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | A substrate for protein kinase C, its phosphorylation is important for platelet secretion. | 532 | |||||

| Nidogen | NIDO_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Glycoprotein found in basement membranes, interacts with laminin, collagon, and integrin on neutrophils. | — | |||||

| Fibrinogen-type protein | Q8VCM7 | No | No evidence | Similar to fibrinogen. | — | |||||

| Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 2 | GDIS_MOUSE | Yes | No evidence | Regulates the GDP/GTP exchange reaction of Rho proteins. Regulates platelet aggregation. Involved in exocytosis in mast cells. | 97 | |||||

| Rho GTPase activating protein | Q92512 | Yes | No evidence | Promotes the intrinsic GTP hydrolysis activity of Rho family proteins. Involved in regulating myosin phosphorylation in platelets. | * | |||||

| Transgelin | TAG2_HUMAN | No | No evidence | Actin-binding protein. Loss of transgelin expression important in early tumor progression. May serve as a diagnostic marker for breast and colon cancer. | 7 | |||||

| Vinculin | VINC_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Actin-binding protein. | 44 | |||||

| WD-repeat protein | WDR1_HUMAN | No | No evidence | Actin-binding protein. | 127 | |||||

| Superoxide dismutase (SOD) | SODC_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Important enzyme in cellular oxygen metabolism, role for SOD-1 in inflammation. | 1730 | |||||

| 78-kDa glucose-related protein | GR78_MOUSE | No | No evidence | Chaperone in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) involved in inhibition of secreted coagulation factors thus reducing prothrombotic potential of cell. | — | |||||

| Bromodomain and PHD finger-containing protein 3 (fragment) | BRF3_HUMAN | No | No evidence | Unknown. | * | |||||

| Titin | Q8WZ42 | Yes | No evidence | Anchoring protein of actinomyosin filaments. Role in secretion of myostatin. | — | |||||

| Similar to hepatocellular carcinoma-associated antigen 59 | Q99JW3 | No | No evidence | Tumor marker. | — | |||||

| FKSG30 | Q9BYX7 | No | No evidence | Actin-binding protein. | * | |||||

| RNA-binding protein | Q9UQ35 | No | No evidence | RNA-binding protein. | — | |||||

| Hypothetical protein | Q9BTV9 | No | No evidence | Unknown. | 1744 | |||||

| Intracellular hyaluronan-binding protein p57 | Q9JKS5 | No | No evidence | Unknown. | — | |||||

| Hypothetical protein | Y586_HUMAN | No | No evidence | Unknown. | * | |||||

| Filamin fragment (hypothetical 54-kDa protein) | Q99KQ2 | Yes | No evidence | Unknown. | — | |||||

| Filamin | FLNA_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Actin-binding protein. Essential for GP 1b-α anchorage at high shear. Substrate for caspase-3. | 43 | |||||

| Talin | TALI_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Actin-binding protein that binds to integrin-β3 domain. | 17 | |||||

| Zyxin | ZYX_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Associates with the actin cytoskeleton near adhesion plaques. Binds α actinin and VASP. | 145 | |||||

Name . | Accession no. . | Known platelet protein . | Known to be released/exocytosed . | Function . | mRNA rank in platelets . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROTEINS IN THE PLATELET RELEASATE KNOWN TO BE RELEASED FROM PLATELETS | ||||||||||

| Thrombospondin 1 | TSP1_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | On secretion, can bind αIIbβ3, αvβ3, and GPIV. Can potentiate aggregation by complexing with fibrinogen and becoming incorporated into fibrin clots. | 213 | |||||

| Fibrinogen α chain | FIBA_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Cofactor in platelet aggregation. Endocytosed into platelets from plasma. | 632 | |||||

| Fibrinogen γ chain | FIBG_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Cofactor in platelet aggregation. Endocytosed into platelets from plasma. | — | |||||

| Platelet basic protein | SZ07_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Proteolytic cleavage yields the chemokines β-thromboglobulin and neutophil-activating peptide (NAP) 2. | 23 | |||||

| PF4 | PLF4_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Platelet-specific chemokine with neutrophil-activating properties. | 8 | |||||

| Serum albumin | ALBU_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Major plasma protein secreted from the liver into the blood. Endocytosed into platelets from plasma. | — | |||||

| Endothelial cell multimerin | ECM_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Carrier protein for platelet factor V/Vα. | — | |||||

| SPARC (osteonectin) | SPRC_MOUSE | Yes | From platelet α-granules | On secretion, forms a specific complex with thrombospondin. | 14 | |||||

| α-actinin I | AAC1_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Actin-binding and actinin cross-linking protein found in platelet α-granules. Interacts with thrombospondin on the platelet surface. | 171 | |||||

| α1-antitrypsin | A1AT_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Acute phase protein, similar to complement, inhibits proteinases. | — | |||||

| Fibrinogen β chain | FIBB_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Cofactor in platelet aggregation. Endocytosed into platelets from plasma. | — | |||||

| Factor V | FA5_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Cofactor that participates with factor Xa to activate prothrombin to thrombin. | — | |||||

| Secretory granule proteoglycan core protein | PGSG_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Function unknown. Associates and coreleased with inflammatory mediators such as PF4. | 343 | |||||

| Thymosin β-4 | TYB4_MOUSE | Yes | From platelets α-granules | G actin—binding protein. Functions as an antimicrobial peptide when secreted. | 5 | |||||

| Fructose biphosphate aldolase | ALFA_MOUSE | Yes | From platelets and exosomes from dendritic cells | Glycolytic enzymes that convert fructose 1,6-bis phosphate to glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate and dihydroxy acetone phosphate. | 79 | |||||

| Clusterin | CLUS_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Not clear. Possibly platelet-derived apolipoprotein J participates in short-term wound repair and chronic pathogenic processes at vascular interface. | 1 | |||||

| Coagulation factor XIIIA chain | F13A_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Coagulation protein involved in the formation of the fibrin clots. | 19 | |||||

| Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 | TIM1_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Interacts with metalloproteinases and inactivates them. Stimulates growth and differentiation of erythroid progenitors, dependent on disulfide bonds. | 112 | |||||

| Platelet glycoprotein V | GPV_HUMAN | Yes | Cleaved from platelet surface | Part of the GPIb-IX-V complex on the platelet surface. Cleaved by the protease thrombin during thrombin-induced platelet activation. | — | |||||

| von Willebrand factor | VWF_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Binds GPIb-IX-V. | 2465 | |||||

| Amyloid β-A4 protein (protease nexin II | A4_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Exhibits potent protease inhibitor and growth factor activity. May play a role in coagulation by inhibiting factors XIa and IXa. | 379 | |||||

| Latent transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-binding protein isoform 1S | LTBS_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Subunit of the TGF-β1 complex secreted from platelets. | — | |||||

| α-Actinin 2 | AAC2_MOUSE | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Actin-binding and actinin cross-linking protein found in platelet α-granules. Interacts with thrombospondin on the platelet surface. | — | |||||

| Latent TGF-β—binding protein 1L | O88349 | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Subunit of the TGF-β1 complex secreted from platelets. | 617 | |||||

| Proactivator polypeptide | SAP_HUMAN | Yes | From lysosomes | Activator proteins for sphingolipid hydrolases (saposins) that stimulate the hydrolysis of sphingolipids by lysosomal enzymes. | 147 | |||||

| Platelet glycoprotein 1b α chain | GPBA_HUMAN | Yes | Cleaved from platelet surface (glycocalicin) | Surface membrane protein of platelets that participates in formation of platelet plug by binding A1 domain of von Willebrand factor. | 26 | |||||

| Vitamin K—dependent protein S | PRTS_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Cofactor to protein C in the degradation of coagulation factors Va and VIIIA. | 1810 | |||||

| PF4 variant | PF4V_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Platelet-specific chemokines with neutrophil-activating properties. | 346 | |||||

| α2-macroglobulin | A2MG_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Acute phase protein, similar to compliment, inhibits proteinases. | * | |||||

| α-actinin 4 | AAC4_HUMAN | Yes | From platelet α-granules | Actin-binding and actinin cross-linking protein found in platelet α-granules. Interacts with thrombospondin on the platelet surface. | 467 | |||||

| SECRETORY PROTEINS IN THE PLATELET RELEASATE NOT PREVIOUSLY IDENTIFIED IN PLATELETS | ||||||||||

| Vitamin D—binding protein | VTDB-HUMAN | No | From liver to plasma | Carries vitamin D sterols. Prevents actin polymerization. Has Tlymphocyte surface association. | — | |||||

| β2-microglobulin | B2MG_HUMAN | No | Exosomes from dendritic cells, B cells, enterocytes, tumor cells, and T cells | Is the β chain of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecule. | 3 | |||||

| Hemoglobin α chain | HBA_HUMAN | No | Exosomes from dendritic cells and phagosomes in macrophages | Oxygen transport. Potentiates platelet aggregation through thromboxane receptor. | 21 | |||||

| Plasminogen | PLMN_HUMAN | Yes | From kidney into plasma | Dissolves fibrin in blood clots, proteolytic factor in tissue remodeling, tumor invasion, and inflammation. | — | |||||

| Serotransferrin | TRFE_HUMAN | Yes | From liver into plasma | Precursor to macromolecular activators of phagocytosis (MAPP), which enhance leukocyte phagocytosis via the FcγRII receptor. | — | |||||

| Pyruvate kinase, M2 isozyme | KPY2_MOUSE | Yes | B-cell exosomes | Involved in final stage of glycolysis. Presented as an autoantigen by dendritic cells. | 61 | |||||

| Actin, aortic smooth muscle | ACTA_HUMAN | Yes | Exosomes from B cells, dendritic cells, enterocytes, and mastocytes | Major cytoskeletal protein. | — | |||||

| Actin | ACTB_HUMAN | Yes | Exosomes from B cells, dendritic cells, enterocytes, and mastocytes | Major cytoskeletal protein. External function unknown. | 11 | |||||

| 14-3-3 protein ζ/δ | 143Z_MOUSE | Yes | Exosomes from dendritic cells and phagosomes in macrophages | External function unknown. Involved intracellularly in signal transduction, however, may have a role in regulating exocytosis. | 63 | |||||

| Hemopexin | HEMO_HUMAN | No | From liver to plasma | Haem-binding protein with metalloproteinase domains. | — | |||||

| Hemoglobin β chain | HBB_HUMAN | No | From liver to plasma and phagosomes from macrophages | Oxygen transport. | 9 | |||||

| Peptidyl-prolyl-cis isomerase A (cyclophilin A) | CYPH_MOUSE | No | From smooth muscle cells | Cellular protein with isomerase activity. Secreted vascular smooth muscle cell growth factor. | 116 | |||||

| Calumenin | CALU_MOUSE | No | From many cells, including fibroblast and COS cells | An inhibitor of the vitamin K epoxide reductase-warfarin interaction. | 1816 | |||||

| Adenylyl cyclase—associated protein 1 (CAP 1) | CAP1_MOUSE | No | Phagosomes from macrophages | Contains a WH2 actin-binding domain (as β-thymosin 4). Known to regulate actin dynamics. May mediate endocytosis. | 174 | |||||

| Tubulin | TBA1_HUMAN | Yes | Exosomes from dendritic cells and phagosomes from macrophages | Cytoskeletal protein involved in microtubule formation. | 33 | |||||

| Apolipoprotein A-1 | APA1_HUMAN | Yes | From liver to plasma, from monocytes and exosomes of dendritic cells | Role in high-density lipoprotein binding to platelets. | — | |||||

| Compliment C3 | CO3_HUMAN | No | From liver cells and monocytes | Activator of the compliment system. Cleaved to α, β, and γ chains normally prior to secretion and is a mediator of the local inflammatory response. | * | |||||

| Transthyretin | TTHY_HUMAN | No | From choroid plexus into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) | Thyroid hormone—binding protein secreted from the choroid plexus and the liver into CSF and plasma, respectively. | — | |||||

| Cofilin | COF1_MOUSE | Yes | Exosome from dendritic cells | Actin demolymerization/regulation in cytoplasm. | 31 | |||||

| Profilin | PRO1_MOUSE | Yes | Exosome from dendritic cells | Actin demolymerization/regulation in cytoplasm. | 70 | |||||

| Secretogranin III | SG3_MOUSE | No | From neuronal cells | Unclear; possibly involved in secretory granule biogenesis. May be cleaved into active inflammatory peptide like secretogranin II. | * | |||||

| Phosphoglycerate kinase | PGK1_MOUSE | Yes | From tumor cells | Glycotic enzyme. Secreted from tumor cells and involved in angiogenesis. | 378 | |||||

| α-IB glycoprotein | AIBG_HUMAN | No | From many cell including white blood cells | Found in plasma, not clear, possibly involved in cell recognition as a new member of the immunoglobulin family. | * | |||||

| Compliment C4 precursor | CO4_HUMAN | No | From many cells including white blood cells | Activator of the compliment system. Cleaved normally prior to secretion, its products mediate the local inflammatory response. | — | |||||

| Prothrombin | THRB_HUMAN | No | From liver to plasma | Converts fibrinogen to fibrin and activates coagulation factors including factor V. | 2143 | |||||

| Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | G3P2_HUMAN | Yes | From B-cell exosomes and phagosomes from macrophages | Mitochondrial enzyme involved in glycolysis. May catalyze membrane fusion. | 60 | |||||

| α1-acid glycoprotein | A1AH_HUMAN | No | From liver to plasma | Modulates activity of the immune system during the acute phase reaction. Binds platelet surface. | — | |||||

| Gelsolin | GELS_HUMAN | Yes | Secreted isoform released from liver and adipocytes | Two isoforms, a cytoplasmic actin modulating protein and a secreted isoform involved in the inflammatory response. | 438 | |||||

| PROTEINS IN THE PLATELET RELEASATE NOT PREVIOUSLY REPORTED TO BE RELEASED FROM ANY CELL | ||||||||||

| Calmodulin | CALM_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Known to regulate calcium-dependent acrosomal exocytosis in neuroendocrine cells. | 55 | |||||

| Pleckstrin | PLEK_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | A substrate for protein kinase C, its phosphorylation is important for platelet secretion. | 532 | |||||

| Nidogen | NIDO_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Glycoprotein found in basement membranes, interacts with laminin, collagon, and integrin on neutrophils. | — | |||||

| Fibrinogen-type protein | Q8VCM7 | No | No evidence | Similar to fibrinogen. | — | |||||

| Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 2 | GDIS_MOUSE | Yes | No evidence | Regulates the GDP/GTP exchange reaction of Rho proteins. Regulates platelet aggregation. Involved in exocytosis in mast cells. | 97 | |||||

| Rho GTPase activating protein | Q92512 | Yes | No evidence | Promotes the intrinsic GTP hydrolysis activity of Rho family proteins. Involved in regulating myosin phosphorylation in platelets. | * | |||||

| Transgelin | TAG2_HUMAN | No | No evidence | Actin-binding protein. Loss of transgelin expression important in early tumor progression. May serve as a diagnostic marker for breast and colon cancer. | 7 | |||||

| Vinculin | VINC_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Actin-binding protein. | 44 | |||||

| WD-repeat protein | WDR1_HUMAN | No | No evidence | Actin-binding protein. | 127 | |||||

| Superoxide dismutase (SOD) | SODC_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Important enzyme in cellular oxygen metabolism, role for SOD-1 in inflammation. | 1730 | |||||

| 78-kDa glucose-related protein | GR78_MOUSE | No | No evidence | Chaperone in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) involved in inhibition of secreted coagulation factors thus reducing prothrombotic potential of cell. | — | |||||

| Bromodomain and PHD finger-containing protein 3 (fragment) | BRF3_HUMAN | No | No evidence | Unknown. | * | |||||

| Titin | Q8WZ42 | Yes | No evidence | Anchoring protein of actinomyosin filaments. Role in secretion of myostatin. | — | |||||

| Similar to hepatocellular carcinoma-associated antigen 59 | Q99JW3 | No | No evidence | Tumor marker. | — | |||||

| FKSG30 | Q9BYX7 | No | No evidence | Actin-binding protein. | * | |||||

| RNA-binding protein | Q9UQ35 | No | No evidence | RNA-binding protein. | — | |||||

| Hypothetical protein | Q9BTV9 | No | No evidence | Unknown. | 1744 | |||||

| Intracellular hyaluronan-binding protein p57 | Q9JKS5 | No | No evidence | Unknown. | — | |||||

| Hypothetical protein | Y586_HUMAN | No | No evidence | Unknown. | * | |||||

| Filamin fragment (hypothetical 54-kDa protein) | Q99KQ2 | Yes | No evidence | Unknown. | — | |||||

| Filamin | FLNA_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Actin-binding protein. Essential for GP 1b-α anchorage at high shear. Substrate for caspase-3. | 43 | |||||

| Talin | TALI_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Actin-binding protein that binds to integrin-β3 domain. | 17 | |||||

| Zyxin | ZYX_HUMAN | Yes | No evidence | Associates with the actin cytoskeleton near adhesion plaques. Binds α actinin and VASP. | 145 | |||||

Eighty-one proteins were identified using MudPIT from the thrombin-stimulated platelet supernatant fraction. Spectra were identified using the SEQUEST program and a composite mouse and human database (NCBI July 2002 release) in 3 replicate experiments. Information on their functions and whether they are secretory proteins are provided. Also indicated is whether these proteins have a corresponding platelet mRNA. The rank of abundance of the message is denoted numerically in the last column.

— indicates levels below the threshold for detection on the Affymetrix microarray; *, not present on Affymetrix microarray.

Thirty-seven percent of the proteins identified were previously reported to be released from platelets including thrombospondin,30 PF4,31 osteonectin,32 metalloproteinase inhibitor 1,33 and transforming growth factor.34 Another 35% are known to be released from other secretory cells. These include cofilin, profilin, 14-3-3 ζ and actin from dendritic cells,12 peptidyl-prolyl-cis isomerase (cyclophilin A) from smooth muscle cells,35 phosphoglycerate kinase from fibrosarcoma cells,36 and β2-microglobulin37 and vitamin D–binding protein38 from the liver. The remaining proteins are not known to be released from any cell type with several mapping to expressed sequence tags (ESTs) of unknown function (Table 2). Additionally, 75 of the 81 released proteins were matched to UniGene clusters, 68 of which had corresponding Affymetrix probe sets. Of these 68 array-comparable proteins, messages for 46 (68%) were detected in the platelet mRNA (J.P.M. et al, manuscript submitted; Table 2).

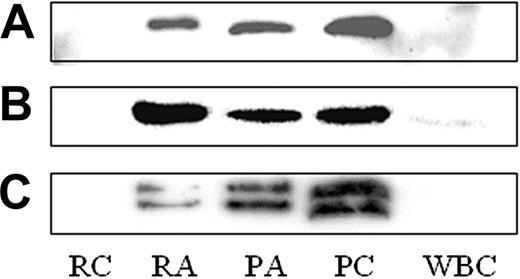

We focused on 3 proteins, secretogranin III (SgIII), cyclophilin A, and calumenin, which are not known to be present in or released from platelets. SgIII (Figure 4C), cyclophilin A (Figure 4B), and calumenin (Figure 4A) were found by Western blot in resting (PC) and thrombin-activated platelet lysates (PA), as well as in the supernatant of thrombin-activated platelets (RA; Figure 4). Neither SgIII nor calumenin was detected in a crude leukocyte lysate (white blood cells [WBCs]), although cyclophilin A was present in low amounts (Figure 4). These 3 proteins were identified in P-selectin–positive platelets by flow cytometry (data not shown) and in CD41+ platelets adhering to fibrinogen-coated slides using confocal microscopy (Figure 5B). No staining was observed in platelets stained for secondary antibody only (Figure 5C).

Western blot for calumenin, cyclophilin A, and secretogranin III. The presence of calumenin (A), cyclophilin 4 (B), and secretogranin III (C) was confirmed in lysates from control (platelet control, PC) and thrombin-activated (platelet activated, PA) platelets, as well as the thrombin-activated releasate (releasate activated, RA). These proteins were not found in the supernatant from unactivated platelets (releasate control, RC). In addition, SgIII and calumenin were not detected in a crude leukocyte lysate (WBC), although cyclophilin 4 was present in low amounts.

Western blot for calumenin, cyclophilin A, and secretogranin III. The presence of calumenin (A), cyclophilin 4 (B), and secretogranin III (C) was confirmed in lysates from control (platelet control, PC) and thrombin-activated (platelet activated, PA) platelets, as well as the thrombin-activated releasate (releasate activated, RA). These proteins were not found in the supernatant from unactivated platelets (releasate control, RC). In addition, SgIII and calumenin were not detected in a crude leukocyte lysate (WBC), although cyclophilin 4 was present in low amounts.

Confocal microscopy for calumenin, cyclophilin A, and secretogranin III. (A) Platelets were adhered to fibrinogen-coated slides for 5 (platelets resting) and 60 minutes (platelets activated and spread). A granular staining pattern similar to thrombospondin was observed for cyclophilin A and secretogranin III at both time points, whereas a more diffuse pattern was observed for calumenin. (B) Activated platelets labeled with CD41 and a rhodamine-labeled secondary antibody, and dual stained with antibodies to secretogranin III, cyclophilin A, and calumenin (labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]–conjugated secondary antibodies). (C) Secondary antibodies alone. Original magnification × 63.

Confocal microscopy for calumenin, cyclophilin A, and secretogranin III. (A) Platelets were adhered to fibrinogen-coated slides for 5 (platelets resting) and 60 minutes (platelets activated and spread). A granular staining pattern similar to thrombospondin was observed for cyclophilin A and secretogranin III at both time points, whereas a more diffuse pattern was observed for calumenin. (B) Activated platelets labeled with CD41 and a rhodamine-labeled secondary antibody, and dual stained with antibodies to secretogranin III, cyclophilin A, and calumenin (labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]–conjugated secondary antibodies). (C) Secondary antibodies alone. Original magnification × 63.

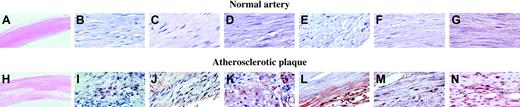

Sections of arterial tissue from 5 patients with atherosclerosis were examined using immunohistochemistry.26 The results from a representative patient are shown (Figure 6). Low-power hematoxylin and eosin staining of normal (A) and atherosclerotic plaque (H) are provided for orientation of these sections. Atherosclerotic but not normal artery stained for the platelet-specific proteins PF4 (Figure 6J) and CD41 (Figure 6I). SgIII (Figure 6L) and calumenin (Figure 6M) were also expressed widely in the plaque, whereas vascular smooth muscle cells in the lesion, identified by staining for actin (Figure 6G,N), stained for cyclophilin A (Figure 6K). None of the proteins were found in normal artery (Figure 6B-F).

Immunohistochemistry of normal and atherosclerotic tissue. Immunohistochemistry for each of the 3 proteins was performed on sections of arterial tissue from 5 patients with atherosclerosis. The results from one representative patient are shown. Low-power hematoxylin and eosin staining of normal (A) and atherosclerotic plaque (H). Platelet incorporation into the plaques was demonstrated by staining for the platelet-specific proteins PF4 (J) and CD41 (I). Secretogranin III (L) and calumenin (M) were widely expressed in the plaque, whereas vascular smooth muscle cells in the lesion, identified by smooth muscle actin staining (G,N), stained for cyclophilin A (K). No staining for secretogranin III, calumenin, or cyclophilin A was observed in sections of normal artery (B-F). Original magnification × 2.5 (A, H); × 63 (B-G, I-N).

Immunohistochemistry of normal and atherosclerotic tissue. Immunohistochemistry for each of the 3 proteins was performed on sections of arterial tissue from 5 patients with atherosclerosis. The results from one representative patient are shown. Low-power hematoxylin and eosin staining of normal (A) and atherosclerotic plaque (H). Platelet incorporation into the plaques was demonstrated by staining for the platelet-specific proteins PF4 (J) and CD41 (I). Secretogranin III (L) and calumenin (M) were widely expressed in the plaque, whereas vascular smooth muscle cells in the lesion, identified by smooth muscle actin staining (G,N), stained for cyclophilin A (K). No staining for secretogranin III, calumenin, or cyclophilin A was observed in sections of normal artery (B-F). Original magnification × 2.5 (A, H); × 63 (B-G, I-N).

Discussion

We identified more than 300 proteins in the platelet releasate; a fraction highly enriched for platelet granular and exosomal contents. This list included proteins of relatively low (eg, thrombospondin) and high (eg, platelet glycoprotein V) isoelectric point, as well as low (eg, PF4) and high (eg, von Willebrand factor) molecular mass. Of the 81 proteins observed in 2 or 3 repeat experiments, 30 (37%) are known to be released from platelets including multimerin, thrombospondin, and PF4. Integral membrane proteins, such as αIIb and known signaling proteins, were not represented, suggesting that the identified fraction is relatively specific and enriched for secreted and exosomal proteins.

Fifty-one (63%) of the proteins identified were not known to be released from platelets. A possible explanation for the presence of these proteins is contamination of the releasate with intracellular platelet proteins released by platelet lysis. However, the absence of major signaling proteins argues against this. Furthermore, 28 (35%) of the identified proteins are proteins that are released by other secretory cells (Table 2). For example, a number of the platelet releasate proteins identified, including tubulin and adenylyl cyclase–associated protein (CAP 1) are found in macrophage phagosomes.39 Other proteins identified in the releasate fraction may be involved in the process of exocytosis, for example, calmodulin.40 Furthermore, neither vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP) nor syntaxins, which are present in high amounts in platelets,41 appear in the releasate.

Twenty-three (28%) proteins in the releasate are not reported to be released from any cell type. Several map to ESTs of unknown function. However, of 81 proteins found consistently in the platelet releasate, 46 were detected at the mRNA level in platelets (J.P.M. et al, manuscript submitted; Table 2). Remarkably, 18 of the 50 most abundant platelet messages were represented in the releasate. Protein synthesis in the platelet is limited42 and the platelet transcriptome may largely reflect that of the parent megakaryocyte.43 The messages for many secreted proteins may, therefore, be transcribed in the megakaryocyte and passed to the daughter platelet cells. Other proteins released that do not have a corresponding mRNA may be endocytosed by platelets, for instance, fibrinogen44 and albumin.45 Although the detection of hemoglobin messages in platelet RNA might point to contamination of the platelet preparations, our platelet RNA results are in close agreement with those of Gnatenko et al,46 whose comparison of the transcriptomes from platelets, erythrocytes, and whole blood suggests that mRNAs for hemoglobin are present in platelets.

A number of cytoskeletal and actin-binding proteins were found in the thrombin-activated releasate. Changes in the actin cytoskeleton on platelet activation play an important role in granule movement and exocytosis and many ubiquitous actin-binding proteins interact with endosomes and lysosomes.47 Moreover, α-actinin and thymosin-β4 are known to be released from platelet α-granules,48 where they bind thrombospondin and exhibit antimicrobial activity, respectively.49 Many of the other actin-binding proteins identified are released from other cells including profilin, cofilin, actin, and tubulin from exosomes of dendritic cells.12 Interestingly, the widely expressed intermediate filament protein vimentin is secreted by activated macrophages, where it is involved in bacterial killing and the generation of oxidative metabolites.50

Five mitochondrial proteins were identified including pyruvate kinase, fructose biphosphate aldolase, phosphoglycerate kinase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and superoxide dismutase. The most straightforward explanation for these proteins would be mitochondrial contamination; however, 2 of the most abundant mitochondrial proteins, fumarate hydratase and aconitase, are not present in our preparation.51 Although there are no reports of superoxide dismutase secretion, pyruvate kinase and GAPDH are released from B cells,13 fructose biphosphate aldolase is released from dendritic cells,12 and phosphoglycerate kinase is released from tumor cells.36

Three proteins, SgIII, cyclophilin A, and calumenin, not previously recognized to be present in or released by platelets, were examined further because they are of potential interest in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. These 3 proteins were localized to platelets by Western blotting, confocal microscopy, flow cytometry, and, for cyclophilin A and calumenin, by microarray analysis of mRNA. Although absent from normal artery, these 3 proteins were found in human atherosclerotic plaque. These lesions also stained for CD41 and PF4, 2 platelet-specific proteins. We have previously demonstrated CD41 staining as a marker for platelets in the atherosclerosis of the ApoE–/– model.52 In addition, PF4 and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) have been found to colocalize in atherosclerotic lesions, especially in macrophage-derived foam cells, as PF4 binds to oxidized LDL and may contribute to its uptake.53

SgIII is a member of the chromogranin family of acidic secretory proteins, previously shown only to be localized to storage vesicles of neuronal and endocrine cells.54,55 Secreteogranin II, a close homolog also found in our platelet releasate (n = 1; see the online data supplement), is present in neuroendocrine storage vesicles and is the precursor of the neuropeptide secretoneurin, which has a tissue distribution and function similar to the proinflammatory neuropeptides, substance P and neuropeptide Y. Secretoneurin stimulates monocyte adhesion to the vessel wall followed by their transendothelial migration.56 Whether cleavage products of SgIII play a similar role is unknown.

Cyclophilins are peptidyl-propyl cis-trans-isomerases that act intracellularly both as catalysts and chaperones in protein folding57 and have extracellular signaling functions such as the induction of chemotaxis and adhesion of memory CD4 cells.58 Recently, cyclophilin A was found to be secreted by vascular smooth muscle cells in response to oxidative stress, where it acted in an autocrine manner to stimulate extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) activation and vascular smooth muscle proliferation.35 Therefore, cyclophilin A released from activated platelets may stimulate the migration and proliferation of smooth muscle cells, a process implicated in the development of atherosclerosis.

The third protein, calumenin, belongs to the CREC family of calcium-binding proteins and was recently found to be secreted from early melanosomes, which are closely related to platelet dense granules.59 Calumenin has a chaperone function in the endoplasmic reticulum, but little is known about its extracellular function.60 It has, however, been shown to bind to serum amyloid P component, which is also released from platelets (Table 2).61 Calumenin inhibits the activity of vitamin K–dependent γ-carboxylation62 responsible for the activation of coagulation factors and proteins such as matrix Gla protein (MGP).63 Both calumenin and warfarin target the enzyme vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR), an integral membrane complex, which converts vitamin K to its hydroquinone form, a cofactor for the enzyme γ-carboxylase, thus inhibiting the γ-carboxylation.62 Mice deficient in MGP, which inhibits bone morphogenetic protein activity, develop complete ossification of the aorta, presumably as a result of unopposed osteogenic activity on vascular mesenchyme.64 Because MGP function requires γ-carboxylation in the aortic vessel wall, warfarin treatment and, indeed, presumably, calumenin deposition in atherosclerotic plaques, may promote vascular calcification by blocking vitamin K–dependent γ-carboxylation and hence MGP activity.65

In conclusion, platelet adhesion contributes to the development of atherosclerosis, possibly through proteins released from platelets on activation. SgIII, cyclophilin A, and calumenin are potential candidates given their known biologic activity, and such extracellular platelet proteins may prove suitable as therapeutic targets. Indeed, inhibition of platelet-derived proteins, such as CD40 ligand, reduces the development of atherosclerosis in mice.66 Thus, the targeting of selected secreted platelet proteins may provide a novel means of modifying atherosclerosis without the risk associated with direct inhibition of platelet adhesion.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 20, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2804.

Supported in part by a fellowship from Enterprise Ireland (P.B.M.), research grants from the Health Research Board of Ireland (P.B.M., O.B., and D.J.F.), and the Higher Education Authority of Ireland (D.J.F., G.C., and D.J.C.). G.C. and D.J.C. are recipients of Science Foundation Ireland awards (grants no. 02/IN.1/B117 and 02/CE.1/B141). T.K. and A.E. are supported by the Research Council of Canada.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We would like to thank Gerardene Meade, Pamela Connolly, Michelle Dooley, and Dermot Cox for technical assistance with confocal microscopy and flow cytometry.

![Figure 5. Confocal microscopy for calumenin, cyclophilin A, and secretogranin III. (A) Platelets were adhered to fibrinogen-coated slides for 5 (platelets resting) and 60 minutes (platelets activated and spread). A granular staining pattern similar to thrombospondin was observed for cyclophilin A and secretogranin III at both time points, whereas a more diffuse pattern was observed for calumenin. (B) Activated platelets labeled with CD41 and a rhodamine-labeled secondary antibody, and dual stained with antibodies to secretogranin III, cyclophilin A, and calumenin (labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]–conjugated secondary antibodies). (C) Secondary antibodies alone. Original magnification × 63.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/103/6/10.1182_blood-2003-08-2804/6/m_zh80060458180005.jpeg?Expires=1769983327&Signature=vF7oBGm5o7XX4bmOcjDn1M06~EwbHNKKT4XZh6V1qminHrvsox9vbA3zQF6PSsQoSV6OLvjv3M~JMiTp-VZqpIFJrE8CfbVitP3G9Tquiw9-ynyGdJlIpqq~L-DBIJ~agw8UP6ShFUDknxMpoQWl6b6~2A~auJ7KN0EBxwfpE39rMIcMg8tQmkwuV~OX7ToIFd0c5Js~C8tKllEgjBKLaVIZCmQ7qF~IxXYU8v8NugQyStK~7tnyluTfVtRUnPojlB8cXkfDB3zoxgCo19NWq7agOMZ~0mn8s6776rIiXcKV9DPGiAl~KnujFqW5CVvBb0O1-0Q5TekxUmtFAnOFMw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal