Abstract

Multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) is a lymphoproliferative disorder associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infection among persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Treatment often includes chemotherapy, and progression to non-Hodgkin lymphoma frequently occurs. MCD is characterized in part by active HHV-8 replication, and many of the symptoms of MCD may be attributable to viral gene products. We describe the effect of ganciclovir on the clinical and virologic course of MCD in a series of 3 case reports. Two patients experienced a reduction in the frequency of episodic flares of MCD and detectable HHV-8 DNA with intravenous or oral ganciclovir, whereas the third patient recovered from an acute episode of renal and respiratory failure with intravenous ganciclovir therapy. These data provide in vivo evidence for the utility of antiviral agents against HHV-8 in the management of MCD.

Introduction

Multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) is a lymphoproliferative disorder associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infection among patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).1 The disease is characterized by recurrent lymphadenopathy, fevers, and hepatosplenomegaly,2 and frequent progression to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.3 Although no standard of care for the treatment of MCD has been established, symptomatic recurrences are often treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy,4 corticosteroids,5 interferon,6 or anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies.7 No therapy has been shown to significantly reduce exacerbations or to prevent long-term sequelae.

HHV-8 DNA has been detected more frequently and in higher quantity in the peripheral blood of patients with MCD.8-10 Molecular analysis of HHV-8–infected lymphocytes from patients with MCD shows a high degree of HHV-8 lytic gene activity,11 as well as viral interleukin-6, a product of ongoing HHV-8 replication.12 We report the successful symptomatic treatment of 3 patients with MCD with ganciclovir and present virologic evidence for inhibition of HHV-8 replication with ganciclovir.

Patients, materials, and methods

Case 1

A 37-year-old man with advanced HIV was admitted to the intensive care unit with fever, respiratory failure, and acute renal insufficiency. He had been hospitalized twice in the past 3 months for fever of unknown origin accompanied by pancytopenia and diffuse lymphadenopathy. His most recent laboratories were notable for 85 CD4+ T cells/mL (0.085 × 109/L) and more than 500 000 copies of HIV RNA/mL plasma. He was not taking antiretroviral therapy. A lymph node biopsy obtained during the previous hospitalization was interpreted as “reactive,” although spindle cells (CD34+ and CD31+) that stained positive for HHV-8 orf73 DNA by using in situ hybridization were noted. Broad-spectrum antibiotics, mechanical ventilation, and hemodialysis were initiated without significant clinical improvement.

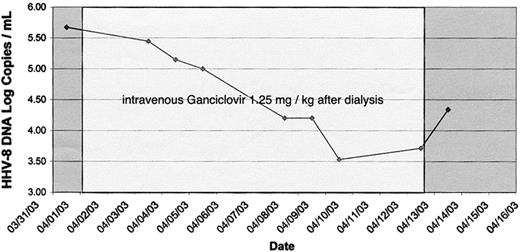

On hospital day 7, 500 000 copies of HHV-8 DNA were detected in 1 mL plasma by real-time polymerase chain reaction by using primers to the orf73 region (forward, 5′-CCA GGA AGT CCC ACA GTG TTC-3′; reverse, 5′-GCC ACC GGT AAA GTA GGA CTA GAC-3′) and the appropriate positive and negative controls.13,14 Additional laboratories revealed 11 110 white blood cells (WBCs) per mL (11.11 × 109/L) and a high-sensitivity c-reactive protein (CRP) of 104 mg/L. Therapy with 1.25 mg/kg intravenous ganciclovir daily after dialysis was started. A rapid improvement in oxygenation, resolution of diffuse airspace opacities on chest roentgenograms, and defervescence was observed, coincident with a decline in plasma HHV-8 DNA (Figure 1). Reduction in HHV-8 viremia was accompanied by a decrease in CRP; on day 4 of ganciclovir the CRP was 66 mg/L and on day 10 it had declined to 39 mg/L. On the 10th day of treatment with ganciclovir, candidemia from a femoral dialysis catheter resulted in a cerebral mycotic aneurysm. Antifungal therapy was initiated, and in light of a decline in WBCs to a nadir of 3920 cells per mL (3.92 × 109/L), ganciclovir was discontinued on day 12 of administration. Despite antifungal therapy, the patient died on the 30th hospital day.

Case 2

A 38-year-old HIV-seropositive man reported fevers, fatigue, dysphagia, and enlarging masses in his neck, axilla, and groin for 1 week. He had been diagnosed with HIV 6 years prior to presentation, declined antiretroviral therapy, and had a CD4 count of 66 cells/mL (0.066 × 109/L) and plasma HIV RNA level of 62 000 copies/mL 15 months prior to the onset of symptoms.

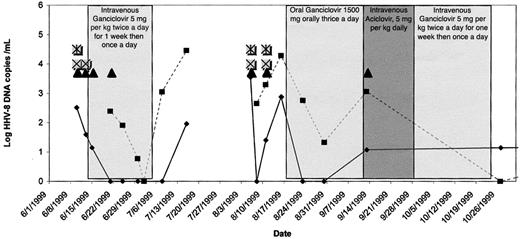

On physical examination, the patient was febrile, had marked hepatosplenomegaly and diffuse lymphadenopathy, and had a Kaposi sarcoma (KS) lesion on the left foot. A lymph node biopsy demonstrated MCD. Immunofluorescence assay detected serum antibodies to latent and lytic HHV-8 antigens, and 325 copies of HHV-8 DNA/mL were detected in plasma (Figure 2). Intravenous ganciclovir, 5 mg/kg twice daily for 1 week and then once daily, led to a rapid resolution of fever, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly; no change in his KS lesion was appreciated. Plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) HHV-8 DNA became undetectable over the course of 4 weeks, at which time ganciclovir was discontinued.

Clinical and virologic course of patient 2. ▪ indicates peripheral blood mononuclear cells; ♦, plasma; ▴, fever; ⊠, lymphadenopathy; *, night sweats.

Clinical and virologic course of patient 2. ▪ indicates peripheral blood mononuclear cells; ♦, plasma; ▴, fever; ⊠, lymphadenopathy; *, night sweats.

For 2 months the patient remained asymptomatic, but then again presented with similar symptoms. Oral ganciclovir, 1500 mg thrice daily, again led to clearance of HHV-8 DNA from the plasma over 1 month, although low levels of HHV-8 DNA persisted in PBMCs. After 1 month, he was hospitalized with aseptic meningitis and was empirically treated with intravenous acyclovir. Ganciclovir was discontinued, and low-level plasma HHV-8 viremia was detected. Intravenous ganciclovir was restarted, but 1 month later, the patient discontinued all medications. Two months after discharge, HHV-8 DNA was again detected in PBMCs.

Three additional episodes of MCD “flares,” consisting of fever, lymphadenopathy, and night sweats, ensued over the next year. Each episode was accompanied by HHV-8 plasma viremia. Elevated CRP (as high as 90 mg/L, returning to normal levels between episodes) and interleukin-6 levels (241 pg/mm3 during the second hospitalization) were observed. Treatment with intravenous ganciclovir led to resolution of symptoms. A third episode of MCD was treated successfully with 7 days of valganciclovir 900 mg orally twice daily, followed by 14 days once daily. Cytopenia was not observed at any point during therapy with ganciclovir or valganciclovir. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was also started at this time. Over the next 18 months, the patient had a CD4 count of more than 200 (0.2 × 109/L) and undetectable plasma HIV RNA, and no subsequent flares of MCD occurred.

Case 3

A 35-year-old Somali woman presented to the clinic, complaining of fatigue, swollen lymph nodes, and night sweats. She had been diagnosed with HIV 8 years prior to presentation, when her CD4 count was found to be 386 cells/mL (0.386 × 109/L) and plasma HIV RNA was 35 000 copies/mL. She took nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and on presentation her CD4 count was 740 cells/mL (0.740 × 109/L), with no HIV RNA detected in plasma. Surgical excision of an inguinal lymph node revealed MCD; latent and lytic antibodies to HHV-8 were present in the serum. Oral valacyclovir was initiated at a dose of 2 g twice daily, but the patient continued to have recurrences of MCD approximately every 6 weeks over the next year. Valacyclovir was discontinued and oral cyclophosphamide was initiated. However, intractable nausea and vomiting resulted in its discontinuation.

Over the next 3 years, she suffered with intermittent bouts of fever, lymphadenopathy, and fatigue, lasting between 5 and 12 days, recurring at 6- to 8-week intervals. HIV infection was well controlled, with a CD4 count remaining more than 1000 cells/mL (1 × 109/L), without detectable HIV RNA in the plasma. Between episodes, qualitative plasma HHV-8 PCR was negative and CRP was 0.97 mg/L. During a particularly severe MCD flare, a repeat CRP was elevated at 120 mg/L, and HHV-8 DNA was detected in plasma. Valganciclovir was started at 900 mg orally twice daily, and symptoms resolved over 48 hours. After completing a total of 7 days of twice daily valganciclovir and an additional 14-day course of once daily therapy, no subsequent flares of MCD have been observed over the past 12 months.

Results

We describe 3 patients with HIV and HHV-8 with clinical improvement in the symptoms of MCD after ganciclovir treatment. Several previous studies suggested that HHV-8–related diseases might be amenable to treatment with antiviral medications. Early population-based studies found the risk of developing KS was significantly lower among persons treated with ganciclovir or foscarnet for cytomegalovirus retinitis.15,16 Antiviral use was associated with reduced HHV-8 viremia coincident with the improvement in clinical symptoms in KS,17 the hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS),18,19 and primary effusion lymphoma (PEL).20 Cidofovir resulted in improvement in MCD and HHV-8 viremia when administered in conjunction with chemotherapy and a monoclonal antibody to interleukin-6,7 whereas foscarnet was ineffective in a patient with MCD who died of disseminated KS shortly after its administration.21

Our study provides preliminary evidence for the importance of ongoing HHV-8 replication in the pathophysiology of MCD. We found symptomatic flares of MCD to be consistently accompanied by HHV-8 viremia, as shown in previous studies.7-9,22 Furthermore, improvement in symptoms mirrored the reduction in HHV-8 plasma or PBMC DNA quantity associated with ganciclovir therapy. If the symptoms of MCD were mediated by either HHV-8 viral gene products or the immune response to viral replication, then the use of antiviral agents would seem appropriate. HHV-8–related disease that may result from the survival or proliferation of latently infected cells, such as KS or PEL, would not be expected to respond to antiviral agents. This situation may be analogous to infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the closest related human herpesvirus to HHV-8. Antivirals may help prevent the development of EBV-related B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders that are characterized by latent EBV and polyclonal tumors23 but have little role in their treatment, a situation analogous to KS.24 Conversely, the response to acyclovir has been documented in fulminant infectious mononucleosis25 and the HPS26,27 in which replication of EBV may play a larger role in the disease process, perhaps analogous to the role of HHV-8 in MCD.

Patient 2 responded to 3 different preparations of ganciclovir, including oral ganciclovir, intravenous ganciclovir, and valganciclovir. Although the dosing of parenteral ganciclovir and oral valganciclovir should have resulted in equivalent levels of ganciclovir in the blood, the dose of oral ganciclovir required to achieve the same levels, approximately 4000 mg thrice daily, is not feasibly administered to patients because of high pill burden and gastrointestinal toxicity. Neither patient in our study responded to preparations of acyclovir, which is consistent with existing in vitro and in vivo studies that have shown no efficacy of acyclovir against HHV-828 or KS.15,29 It is unclear how valganciclovir has led to a long-lasting remission of MCD and clearance of HHV-8 viremia in patient 3, given that the eradication of herpesviruses with antiviral agents is not possible. Although the amount of time since the final episode of MCD occurred is limited in both patients 2 and 3, both intervals represent the longest period during which the patients have remained symptom free. Patient 2 experienced a significant rise in CD4 cells and drop in HIV plasma RNA level with adherence to HAART coincident with his remission of MCD during his third course of treatment with ganciclovir, although patient 3 had little change in her already robust CD4 cell count throughout the course of the study. There appears to be no clear association between immunologic and virologic response to HAART and remission of MCD symptoms.30

Discussion

It remains unknown whether remission of clinical symptoms and/or HHV-8 viremia will be associated with a reduction in the progression to lymphoma. Administration of valganciclovir can result in anemia, neutropenia, and diarrhea,31 and emergence of viral resistance to valganciclovir is a potential concern. Formal controlled trials will be needed to evaluate case series.

Although infection with HHV-8 is common among individuals with HIV infection,32 MCD is an uncommon clinical consequence of HHV-8 infection, making the study of treatment challenging. On the basis of the growing evidence for the activity of ganciclovir and its derivatives against HHV-8 and an increasing understanding of the role of HHV-8 replication in the pathogenesis of HHV-8–related diseases, future studies should be directed at appropriate usage and timing of antiviral medications in the prevention of clinical disease associated with HHV-8 infection. The possibility that antineoplastic chemotherapeutic agents and their associated morbidities could be avoided for the treatment of MCD, as suggested by our study, deserves further investigation.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 13, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1721.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (grants AI 054162 [C.C.], P01 AI30731, U19 AI31448 [M.H., A.W., L.C.], and AI 01839 [W.G.N.]) and the Joel Meyers Infectious Disease Scholarship Grant (C.C.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal