Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) was found to replicate in monocytes/macrophages particularly in patients with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. This study was undertaken to determine whether HIV facilitates HCV infection of native human macrophages in vitro. Monocytes/macrophages were collected from healthy donors, infected with HIV M-tropic molecular clone, and then exposed to HCV-positive sera. Presence of positive and negative HCV RNA strands was determined with a novel strand-specific quantitative real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Preceding as well as near-simultaneous infection with HIV made the macrophages more susceptible to infection with HCV; in particular, an HCV RNA–negative strand was detectable almost exclusively in the setting of concomitant HIV infection. Furthermore, HCV RNAload correlated with HIV replication level in the early stage of infection. The ratio of positive to negative strand in macrophages was lower than in control liver samples. HIV infection was also found to facilitate HCV replication in a Daudi B-cell line with engineered CD4 expression. It seems that HIV infection can facilitate replication of HCV in monocytes/macrophages either by rendering cells more susceptible to HCV infection or by increasing HCV replication. This could explain the presence of extrahepatic HCV replication in HIV-coinfected individuals.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is common in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)–positive patients and each of these infections may affect the other. Thus, several recent reports found an association between HCV coinfection and progression of HIV disease.1-4 It was also reported that HIV infection accelerates the development of severe liver disease.5-8 Paradoxically, the recent reduction in mortality and morbidity among HIV-infected patients could have contributed to the emergence of HCV as a significant pathogen in this population.9

HCV was originally thought to be a strictly hepatotropic virus, but there is mounting evidence that it can also replicate in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), particularly in patients with HIV infection. The infected cells were reported to contain an HCV RNA–negative strand, which is a viral replicative intermediate, and viral genomic sequences were often found to be distinct from those found in serum and liver.10-13 Furthermore, it was also reported that human T- and B-cell lines are capable of supporting HCV infection in vitro14,15 and some viral strains were found to be lymphotropic both in vitro and in vivo in infected chimpanzees.16

Extrahepatic replication of HCV could be facilitated by immunosuppression. For example, the presence of HCV replication was documented in hematopoietic cells inoculated into the severe combined immunodeficiency mice17 and in PBMCs from patients after, but not before, liver transplantation.18 However, there is also evidence that HCV replication may be directly enhanced by the presence of HIV,19,20 and in a previous study the presence of viral replicative forms in lymph nodes and PBMCs did not correlate with CD4 count.21 One of the possibilities is that HIV infection renders PBMCs more susceptible to infection with HCV.

Within the population of PBMCs, the cells harboring replicating virus have been identified as belonging to T-cell and B-cell lineage and monocytes/macrophages.22-24 Infection of macrophages could be consequential: it was reported that chronic HCV infection is associated with an allostimulatory defect and impaired maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells.24-26 Although replication of HCV in macrophages in HIV-coinfected patients is likely, it is unclear whether HIV facilitates this infection indirectly, as a consequence of immunosuppression, or whether there is also some direct effect at play.

The current study provides evidence that HIV facilitates HCV infection of native human macrophages in vitro. The presence of HCV replication was determined by a newly developed strand-specific quantitative real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay.

Patients, materials, and methods

Biologic samples

Sera used for macrophage infections were drawn from 30 HCV-infected patients who presented for clinical care at participating centers. These patients were HCV RNA positive and hepatitis G virus (HGV) RNA negative in serum; all were anti-HIV negative and none received any anti-HCV antiviral therapy prior to blood drawing. The mean viral load of HCV RNA in these patients was 2.2 × 106 copies/mL (range, 1.4 × 106 copies/mL to 2.9 × 106 copies/mL). Twenty-one patients were infected by HCV genotype 1b and 9 were infected by the 1a strain.

Stock preparation of HIV macrophage strain

The HIV infectious stock was prepared by transfecting HeLa cells with the M-tropic pAD8 molecular clone (gift of K. T. Jeang, National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD). In short, cells were grown to 50% to 60% confluency in a T25 flask and transfected with 5 μg plasmid DNA using 30 μL FuGene 6 reagent (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN) following manufacturer's recommendations. Supernatants were harvested 48 hours after transfection and HIV was quantified by reverse transcription (RT) assay.27 In brief, 20 μL of cell culture supernatant was added to 30 μL cocktail (50 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane] Cl, pH 7.8; 63 mM KCl; 4.2 mM MgCl2; 0.08% Nonidet P-40; 0.85 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid]; 4.2 μg/mL polyA; 0.13 μg/mL oligo dT; 4 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]; 2 μL/mL [32P] thymidine triphosphate [TTP]) and incubated for 2 hours at 37° C. Five microliters of the reaction mix was spotted onto diethylamino ethanol (DEAE) paper, fixed twice in 2 × SSC for 30 minutes, and added to 5 mL of scintillation fluid. Counts per mL were read in a scintillation counter (Beckman LS 6000SC; Beckman Coulter, Hialeah, FL); 105 counts per minute (cpm) were used for each macrophage culture (105 cells), since in initial experiments this quantity of virus resulted in infection of 100% of cultures. This quantity corresponded to 108 viral copies as determined by Cobas HIV-1 Monitor Test (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) commercial assay.

Macrophage culture and infection with HIV and HCV

Monocytes/macrophages were collected from healthy donors, isolated by centrifugation over density gradient (Ficoll-Hypaque; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Cells were washed 3 times with Mg2+- and Ca2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) and analyzed by microscopy and flow cytometry to make sure they were free of granulocytes and platelets. To separate macrophages from other cells, PBMCs were resuspended in 10 mL RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco/BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and incubated in plastic 6-well cell culture dishes (Costar, Cambridge, MA), 1.5 mL of suspension per well. After incubation at 37° C for 4 hours, nonadhering cells were removed by washing 4 times with PBS, while adhering cells (approximately 105 cells/well) were maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS. After 24 hours, the cells were exposed for 4 hours to M-tropic HIV and washed 3 times with PBS. After 7 days, the presence of active HIV infection was confirmed by p24 and HIV RNA testing of the supernatant, and the macrophages were incubated for 4 hours with HCV-positive serum diluted 1:10 or 1:1000 in RPMI 1640. Subsequently, the cells were washed 3 times with PBS, and the supernatant containing HIV was added back into the culture. Macrophage cultures were maintained in RPMI with 10% FBS. Half of culture medium was changed every 2 or 3 days and the cultures were terminated 2 weeks after HCV infection. A parallel set of control experiments closely followed the above procedure with the exception that cells were mock infected with HIV. RNA was extracted from cells, 250 μL of cell culture supernatant and 100 μLof serum by means of a modified guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol/chloroform technique using a commercially available kit (TRIZOL LS; Gibco/BRL) and dissolved in 20 μL of water. Five microliters of this RNA solution was used for RT-PCR.

In another set of experiments designed to study the effect of near-simultaneous HIV/HCV exposure, macrophages were cultured for 24 hours, after which they were incubated for 4 hours with M-tropic HIV, washed 3 times with PBS, and immediately incubated for 4 hours with HCV-positive serum diluted 1:10 in RPMI 1640. In parallel control experiments, cells were mock infected with HIV before exposure to HCV. Macrophage cultures were terminated 2 weeks after HIV/HCV exposure.

Strand-specific RT-PCR

Strand specificity of our RT-PCR for the detection of 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) HCV RNA–negative and –positive strands was ascertained by conducting cDNA synthesis at a high temperature with the thermostable enzyme Tth. A detailed description of the assay and sequence of primers was published previously.13,28 In brief, the cDNA was generated in 20 μLof reaction mixture containing 50 pM of sense primer, 1 × RT buffer (Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT), 1 mM MnCl2, 200 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), and 5 U Tth (Perkin Elmer). After 20 minutes at 70° C, Mn2+ were chelated with 8 μL of 10 × EGTA (ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid) chelating buffer (Perkin Elmer), 50 pM of antisense primer was added, the volume was adjusted to 100 μL, and the MgCl2 concentration was adjusted to 2.2 mM. For the detection of positive strands, the primers were added in reverse order. The amplification was performed in Perkin Elmer GenAmp PCR System 9600 thermocycler as follows: initial denaturing for 1 minute at 94° C, followed by 20 cycles of 94° C for 15 seconds, 58° C for 30 seconds, and 72° C for 30 seconds. Two microliters of the final product was directly added into the second-round real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR employed LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche Applied Sciences) and nested primer set.29 Each amplification was followed by melting curve analysis to ensure that a single-size product was amplified and no significant primers-dimers were present. In addition, amplification products were run on agarose gel to confirm the correct product size. Amplification was run in LightCycler (Roche Diagnostics) as follows: initial denaturation and activation of enzyme for 10 minutes at 95° C, followed by 35 cycles of 95° C for 30 seconds, 55° C for 5 seconds, and 72° C for 30 seconds. The above strand-specific assay was capable of detecting approximately 100 genomic equivalent (eq) molecules of the correct strand while unspecifically detecting at least 108 genomic eq of the incorrect strand. Appropriate measures, described elsewhere,13,28 were employed to prevent and detect contamination. Negative controls included macrophages from uninfected subjects and normal sera.

Quantification of HIV RNA by real-time RT-PCR

Amplification was performed using primers specific for the gag gene of HIV. Extracted RNA was incubated for 30 minutes at 37° C in 15 μL of reaction mixture containing 25 pM of antisense primer (5′ CTG AAG GGT ACT AGT AGT TCC TGC TAT GTC ACT T 3′; nucleotides [nt's] 1488 to 1521 of pAD8 clone), 1 × PCR buffer II (Perkin Elmer), 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM dNTP, and 10 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase. The enzyme was deactivated by heating to 99° C for 10 minutes. Two microliters of the RT product were directly added into the real-time PCR mix containing 25 pM of the sense primer (5′ GGA CAT CAA GCA GCC ATG CAA ATG TT 3′; nt's 1366 to 1391). The LightCycler cycling conditions were identical to those used for HCV RNA amplification. Each amplification was followed by melting curve and agarose gel analysis. Synthetic RNA template was generated by “run-off” transcription of cloned PCR products as described previously.28

Detection of proviral HIV DNA by PCR

DNA was extracted from 2 × 104 cells using a commercially available kit (IsoQuick; Orca Research Inc, Bothell, WA) and added directly into the real-time PCR mix. Primes and cycling conditions were identical to those applied for HIV RNA quantification. As tested on serially diluted plasmid template, this assay was capable of detecting approximately 10 template copies and remained linear up to 108 genomic eq (not shown).

Staining of macrophages for p24 HIV antigen and HCV NS3

Macrophages were removed from cell culture plates by gently scraping with a rubber policeman, suspended in PBS (pH 7.5), and counted. Approximately 104 cells were cytospun on a positively charged slide, dried, fixed in 1.5% H2O2/ethanol (EtOH), and permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X-100. After washing in PBS the slides were incubated for 1 hour with anti-p24 antibodies (KC57-FITC; Beckman Coulter) diluted 1:15, washed 3 times with PBS, and 1000 cells were counted under confocal microscope.

For the detection of nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) in infected cells, we employed monoclonal antibody marketed by Novocastra Laboratories (Newcastle, England). Cells were placed on positively charged slides and dried in 42° C for 1 hour, after which they were fixed in 1.5% H2O2 /methanol for 10 minutes and washed with running water. To unmask the antigens, the slides were placed in a pressure cooker and boiled for 10 minutes in the presence of 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Next, the slides were washed twice with 1 × PBS, placed in diluted normal serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 20 minutes, washed in PBS again, and incubated for 1 hour with the primary antibody diluted 1:25. The slides were then again washed in PBS and incubated for 30 minutes with antimouse biotinylated secondary antibody followed by 30 minutes incubation in avidin-biotin complex solution (VECTASTAIN Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories). Finally, the slides were incubated in diaminobenzidine (DAB; DAB Peroxidase Substrate Kit; Vector Laboratories).

HCV genotypes were determined by direct sequencing of the NS5B region.30 HCV RNA was quantified in sera using branched DNA assay (Quantiplex HCV-RNA 2.0; Roche Diagnostics). Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 9.0 package (Chicago, IL). Means were compared by the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test and paired data were compared by Wilcoxon matched pairs test; correlations were tested by Spearman rank test. Proportions were analyzed by Fisher exact test.

Results

Establishment of real-time quantitative RT-PCR for strand-specific detection of HCV RNA

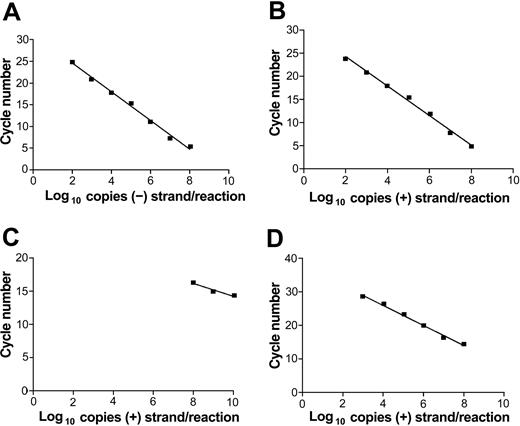

Our previous strand-specific RT-PCR assay was not quantitative and the quantity and ratio of positive and negative HCV RNA strands could be determined only semiquantitatively by serial dilutions.29 The current assay closely follows the original one for RT step and first-round amplification. However, the amplification is limited to 20 cycles, after which 2 μL of the first-round reaction is directly added into the second-round real-time PCR reaction. Since the strand specificity is dependent on the high-temperature RT step, the specificity of the assay is not changed with respect to the previous assay. Figure 1A-B shows that the nested assay was capable of detecting a wide range of synthetic HCV RNA genomic eq molecules (from 102 to 108) while maintaining linearity and remaining strand specific (Figure 1C). The sensitivity of this assay was approximately 10-fold higher than that of the single-round real-time RT-PCR using MMLV reverse transcriptase for the RT step (Figure 1D).

Real-time strand-specific quantitative assay for the detection of HCV RNA–negative and –positive strands. Reverse transcription was done at 70° C using thermostable enzyme Tth and the first round of PCR amplification was limited to 20 cycles. The nested round employed LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche Diagnostics). (A) Detection of negative-strand HCV RNA synthetic template. (B) Detection of positive-strand HCV RNA synthetic template. (C) Specificity of the assay for the detection of negative-strand HCV RNA: reverse transcription was done with positive-sense primer using serial dilution of positive-strand HCV RNA as template. (D) Nonnested real-time PCR detection of HCV RNA–positive strand using MMLV for the reverse transcription step.

Real-time strand-specific quantitative assay for the detection of HCV RNA–negative and –positive strands. Reverse transcription was done at 70° C using thermostable enzyme Tth and the first round of PCR amplification was limited to 20 cycles. The nested round employed LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche Diagnostics). (A) Detection of negative-strand HCV RNA synthetic template. (B) Detection of positive-strand HCV RNA synthetic template. (C) Specificity of the assay for the detection of negative-strand HCV RNA: reverse transcription was done with positive-sense primer using serial dilution of positive-strand HCV RNA as template. (D) Nonnested real-time PCR detection of HCV RNA–positive strand using MMLV for the reverse transcription step.

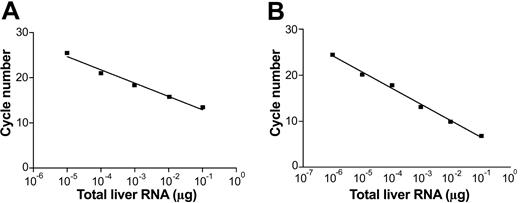

To test the performance of the assay on biologic samples, we used human liver samples, which are supposed to contain both positive and negative HCV RNA strands. Figure 2 shows a typical performance of our assay on RNA extracted from an autopsy liver of an HCV/HIV-coinfected patient. As can been seen, the assay remained linear over the range of 6 10-fold dilutions (from 10–1 to 10–7 μg of liver RNA). Table 1 provides the data on quantity of positive (+) and negative (–) HCV RNA strands in 5 respective livers from HCV-infected patients. Dilutions of synthetic strands of HCV RNA were used as standards. The ratio of (+) to (–) strand ranged from 17 to 90 (mean, 52.7).

Real-time strand-specific quantitative assay for the detection of HCV RNA–negative and –positive strands in liver tissue. One microgram of total RNA was extracted from an infected liver and serially diluted in water; one μg of RNA extracted from uninfected liver was added to each dilution to keep the quantity of RNA constant. (A) Detection of HCV RNA–negative strand: sense primer present in the reverse transcription step. (B) Detection of HCV RNA–positive strand: negative-antisense primer present in the reverse transcription step.

Real-time strand-specific quantitative assay for the detection of HCV RNA–negative and –positive strands in liver tissue. One microgram of total RNA was extracted from an infected liver and serially diluted in water; one μg of RNA extracted from uninfected liver was added to each dilution to keep the quantity of RNA constant. (A) Detection of HCV RNA–negative strand: sense primer present in the reverse transcription step. (B) Detection of HCV RNA–positive strand: negative-antisense primer present in the reverse transcription step.

The quantity and ratio of positive (+) and negative (-) HCV RNA strands in 5 autopsy liver samples as determined by quantitative real-time PCR

Liver ID . | + strand/μg RNA . | - strand/μg RNA . | +/- ratio . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.70 × 104 | 5.20 × 103 | 16.7 |

| 2 | 2.32 × 106 | 2.60 × 104 | 89.2 |

| 3 | 9.46 × 107 | 1.91 × 106 | 49.5 |

| 4 | 4.97 × 107 | 2.37 × 106 | 20.9 |

| 5 | 4.09 × 108 | 4.68 × 106 | 87.4 |

Liver ID . | + strand/μg RNA . | - strand/μg RNA . | +/- ratio . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.70 × 104 | 5.20 × 103 | 16.7 |

| 2 | 2.32 × 106 | 2.60 × 104 | 89.2 |

| 3 | 9.46 × 107 | 1.91 × 106 | 49.5 |

| 4 | 4.97 × 107 | 2.37 × 106 | 20.9 |

| 5 | 4.09 × 108 | 4.68 × 106 | 87.4 |

Infection of native human macrophages with HCV in vitro: facilitation of infection by HIV

The newly established strand-specific assay was employed to determine the presence and quantity of HCV replication in native human macrophages and to elucidate whether infection with HIV would facilitate subsequent infection with HCV. Monocytes/macrophages were collected from healthy donors and after 24 hours of culture were infected with the HIV M-tropic pAD8 molecular clone. At one week, the cells were incubated with 30 different moderate titer (< 3 × 106 copies/mL) HCV-positive sera, which were diluted 1:10; 20 of these sera were also tested at dilution 1:1000. The macrophages were cultured for another 2 weeks, after which RNA was extracted. As seen in Table 2, preceding infection with HIV made the macrophages more susceptible to infection with HCV and/or facilitated HCV replication. In particular, an HCV RNA–negative strand was detectable almost exclusively in the setting of concomitant HIV infection.

Detection of HCV RNA-positive and -negative strands in HIV-positive and HIV-negative macrophage cultures

. | Serum 1:10 . | . | Serum 1:1000 . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | HIV negative . | HIV positive . | HIV negative . | HIV positive . | ||

| HCV RNA (+) | 14/30 | 20/30 | 5/20 | 9/20 | ||

| HCV RNA (-) | 3/30* | 16/30 | 0/20* | 7/20 | ||

. | Serum 1:10 . | . | Serum 1:1000 . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | HIV negative . | HIV positive . | HIV negative . | HIV positive . | ||

| HCV RNA (+) | 14/30 | 20/30 | 5/20 | 9/20 | ||

| HCV RNA (-) | 3/30* | 16/30 | 0/20* | 7/20 | ||

P < .02 by Fisher exact test.

The mean concentration of positive-strand HCV RNA in HIV-positive cultures was higher than in HIV-negative cultures (15 650 ± 7532 vs 7446 ± 5930 copy equivalents/105 cells; P < .05). Interestingly, in contrast to liver tissue, the ratio of positive to negative strand was lower (mean, 5.1; range, 13-0.3). This could point toward differences in replication between liver and extrahepatic sites, or, alternatively, there may be relative dominance of negative strand in the early stages of replication.

Reactions detecting viral-negative strands were unlikely to represent false-positive results because nonspecific detection of the incorrect strand might be expected when the latter is present at a concentration of at least 108 genomic eq/reaction. However, the concentration of HCV RNA in samples containing viral-negative strands was no more than 105 genomic eq/reaction.

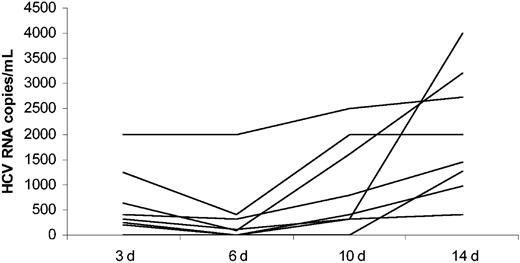

To confirm the presence of HCV replication, HCV RNA was quantified in sequentially collected supernatants from 8 cultures, in which a viral-negative strand was detectable. As shown in Figure 3, there was an overall increase in HCV RNA quantity over the time in every one of 8 analyzed cultures. Interestingly, there was an initial drop in HCV RNA quantity between day 3 and day 6 in the majority of cultures, which probably reflected the presence of serum-derived virus early on and subsequent increase in macrophage viral replication. The increase in HCV RNA quantity over the time of infection was statistically significant (P < .01 by Wilcoxon signed rank test).

Quantitative detection of HCV RNA by real-time RT-PCR in cell culture supernatants from HIV/HCV-coinfected macrophage cultures. Supernatants were collected at day (d) 3, 6, 10, and 14 after exposure to 8 different HCV-positive sera.

Quantitative detection of HCV RNA by real-time RT-PCR in cell culture supernatants from HIV/HCV-coinfected macrophage cultures. Supernatants were collected at day (d) 3, 6, 10, and 14 after exposure to 8 different HCV-positive sera.

To analyze the outcome of near-simultaneous infection, macrophages were exposed in close succession to HIV and HCV or exposed to HCV only (“Patients, materials, and methods”). The cultures were terminated after 2 weeks and the presence of HCV RNA–positive and –negative strands was determined in cell extracts. As shown in Table 3, in all parallel experiments the titer of HCV RNA was higher in cells exposed to HIV (P = .03 by Wilcoxon matched pairs test). An HCV RNA–negative strand was detected in 4 of 6 HIV/HCV-coinfected cultures and in none of the HIV-negative cultures (P = .06).

Quantitative detection of HCV RNA-positive strand in native macrophage cultures exposed to HCV-positive sera either alone or in combination with exposure to HIV

Infecting sera . | Serum 1 . | Serum 2 . | Serum 3 . | Serum 4 . | Serum 5 . | Serum 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV RNA in HIV positive, eq/105 cells | 500 | 1580* | 400* | 7900* | 1800 | 1250* |

| HCV RNA in HIV negative, eq/105 cells | 0 | 0 | 0 | 640 | 560 | 460 |

Infecting sera . | Serum 1 . | Serum 2 . | Serum 3 . | Serum 4 . | Serum 5 . | Serum 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV RNA in HIV positive, eq/105 cells | 500 | 1580* | 400* | 7900* | 1800 | 1250* |

| HCV RNA in HIV negative, eq/105 cells | 0 | 0 | 0 | 640 | 560 | 460 |

Presence of HCV RNA-negative strand

To determine whether similar phenomenon of facilitation of HCV infection by HIV would be present in a different experimental system, we employed Daudi cells (Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]–transformed lymphocytes B), which are susceptible to HCV infection.14 However, as Daudi cells are not susceptible to HIV, we used a Daudi cell line with engineered expression of CD4.31 The cells were infected with pNL4-3–derived HIV, and, after 24 hours, exposed to 6 different HCV-positive sera. The cultures were tested after 8 days (HIV-related apoptosis precluded longer infections). In a parallel experiment, cells were exposed to HCV-positive sera only (no HIV infection). As seen in Table 4, in all 6 parallel cell cultures the titer of HCV RNA load was higher in the HIV-coinfected cells. This difference reached statistical significance (P = .03).

Quantitative detection of HCV RNA-positive strand in HIV-positive and HIV-negative Daudi CD4+ cells exposed to 6 different HCV-positive sera

Infecting sera . | Serum 1 . | Serum 2 . | Serum 3 . | Serum 4 . | Serum 5 . | Serum 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV RNA in HIV positive, eq/105 cells | 1900 | 440 | 2600 | 4620 | 450 | 2900 |

| HCV RNA in HIV negative, eq/105 cells | 560 | 0 | 960 | 590 | 310 | 400 |

Infecting sera . | Serum 1 . | Serum 2 . | Serum 3 . | Serum 4 . | Serum 5 . | Serum 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV RNA in HIV positive, eq/105 cells | 1900 | 440 | 2600 | 4620 | 450 | 2900 |

| HCV RNA in HIV negative, eq/105 cells | 560 | 0 | 960 | 590 | 310 | 400 |

Correlation between HIV and HCV

To elucidate a more clear correlation between HIV and HCV infection, 16 additional macrophage cultures were established using sera, which were found to be infective in the previous experiments. Ten of these cultures were found to be HCV infected as determined by the presence of HCV RNA–positive and –negative strands in cell extracts and these cultures were analyzed further. HIV RNA was measured in cell culture supernatants using real-time RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 4A, this assay was capable of detecting approximately 100 genomic eq molecules of the synthetic RNA template and remained linear up to 109 genomic eq. Figures 4B, 4C, and 4D show correlation between HCV RNA load in cells and HIV RNA quantity in supernatant at time 0, 7, and 14 days, respectively, where time 0 corresponds to the day of HCV exposure. There was a statistically significant positive correlation between HCV RNA load and HIV RNA quantity at time 0 (r = 0.96; P < .01 by Spearman rank correlation test) but not at 7 or 14 days. As shown in Figure 4E-F, the HCV RNA load in cells may have been negatively influenced by the quantity of proviral DNA and the proportion of cells expressing p24 at 14 days, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Correlation between quantitative parameters of HIV and HCV infection in macrophage cultures. (A) Amplification of synthetic HIV RNA template with real-time quantitative RT-PCR: the assay detected 100 template copies and remained linear up to 109 template copies. (B-D) Relationship between HCV RNA cellular load at 2 weeks and HIV RNA quantity in culture supernatant at time 0 (B; right before exposure to HCV), 7 days (C), and 14 days (D) after HCV exposure. There was significant correlation (r = 0.96; P < .01) for HCV RNA and HIV RNA quantity at time 0. (E) Relationship between quantity of HCV RNA and proviral HIV DNA in cells at 2 weeks. (F) Relationship between the quantity of HCV RNA in cells and the percent of cells expressing p24 at 2 weeks. All correlations were calculated by nonparametric Spearman rank test.

Correlation between quantitative parameters of HIV and HCV infection in macrophage cultures. (A) Amplification of synthetic HIV RNA template with real-time quantitative RT-PCR: the assay detected 100 template copies and remained linear up to 109 template copies. (B-D) Relationship between HCV RNA cellular load at 2 weeks and HIV RNA quantity in culture supernatant at time 0 (B; right before exposure to HCV), 7 days (C), and 14 days (D) after HCV exposure. There was significant correlation (r = 0.96; P < .01) for HCV RNA and HIV RNA quantity at time 0. (E) Relationship between quantity of HCV RNA and proviral HIV DNA in cells at 2 weeks. (F) Relationship between the quantity of HCV RNA in cells and the percent of cells expressing p24 at 2 weeks. All correlations were calculated by nonparametric Spearman rank test.

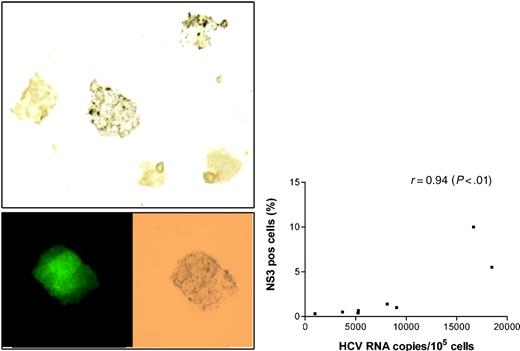

As another way of confirming the presence of active infection, macrophages from the above 10 experiments were stained with monoclonal anti-NS3. These particular antibodies were successfully employed by other groups for liver tissue staining and were recently used for demonstrating persistent HCV infection in immortalized B-cell lines.32 Controls consisted of the same macrophages infected with HIV only (no HCV exposure) and 4 cell cultures in which macrophages were exposed to HCV-positive sera, but subsequent analysis did not detect HCV RNA. The proportion of positively stained cells ranged from 0.3% to 10% (see Figure 5A for an example of positive stain) and this proportion correlated with the HCV RNA viral load measured in the cells (r = 0.94, P < .01; Figure 5B). All control cells infected with HIV only, as well as those exposed to HCV but without subsequent evidence of infection, were negative. Importantly, HCV-infected cells were also positive for p24 staining (Figure 5A).

Staining of HIV/HCV-coinfected macrophages for HCV and HIV antigens. (A) Infected macrophages stained with monoclonal antibodies against nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) and visualized with DAB. Two of 5 macrophages shown demonstrate brown granular cytoplasmic staining (original magnification, × 400). Cell shown in the bottom insert is positive for both p24 (left) and NS3 (right). (B) Relationship between HCV RNA cellular load at 2 weeks and the proportion of cells staining for NS3 (r = 0.94; P < .01 by Spearman rank test).

Staining of HIV/HCV-coinfected macrophages for HCV and HIV antigens. (A) Infected macrophages stained with monoclonal antibodies against nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) and visualized with DAB. Two of 5 macrophages shown demonstrate brown granular cytoplasmic staining (original magnification, × 400). Cell shown in the bottom insert is positive for both p24 (left) and NS3 (right). (B) Relationship between HCV RNA cellular load at 2 weeks and the proportion of cells staining for NS3 (r = 0.94; P < .01 by Spearman rank test).

Discussion

In a previous study we reported the presence of viral replicative forms in monocytes/macrophages from HCV-infected patients.22 The current study extends these findings by demonstrating that native human macrophages are susceptible to HCV infection in vitro and that HIV facilitates this infection. We showed that after exposure to HCV RNA–positive sera in vitro, cultured macrophages can retain HCV RNA for 2 weeks and viral-negative–strand RNA is commonly detected. While the mere presence of HCV RNA in phagocytic cells could come, at least theoretically, from virions entrapped inside these cells or adsorbed on their surface, detection of viral-negative strand argues for the presence of genuine viral replication. Importantly, there was an increase in HCV RNA load in cell culture supernatant over the time of infection, and we also demonstrated the presence of NS3 in cells exposed to HCV-positive sera. Furthermore, there was a highly significant positive correlation between the proportion of infected cells detectable by immunostaining and HCV RNA load in cell extracts.

The mechanisms by which HIV facilitates HCV infection are unclear at present. Positive correlation between HIV viral load at the time of HCV exposure and subsequent level of HCV replication suggests that HIV infection may increase the susceptibility of macrophages to HCV infection perhaps by activation of these cells. No such relationship was evident for HIV measured at 7 and 14 days, and high HIV replication could have even inhibited HCV replication at the late stage of infection, perhaps by taxing cell resources necessary for HCV replication.

Facilitation of extrahepatic HCV replication by HIV could have clinical implications. It has been shown that concomitant HIV infection facilitates vertical33-35 and horizontal36 transmission of HCV and these effects were largely attributed to the enhancement of HCV replication in the setting of immunodeficiency. However, in the only published study analyzing the role of extrahepatic HCV replication in vertical transmission, the presence of both positive and negative viral strands in PBMCs strongly correlated with transmission of infection to infants.37 In the light of our findings demonstrating a facilitating role of HIV for HCV macrophage infection, it is likely that children acquire infection from their mothers through infected cells, probably macrophages. This mechanism would be similar to perinatal transmission of HIV, which involves macrophage-tropic HIV-1 variants.38,39 In a recent study encompassing 75 women, multivariate analysis revealed that local HIV viremia and the presence of HCV RNA in serum were the only independent predictors of HCV RNA in genital tract secretions. Significant (> 600 IU/mL) HCV viremia in cervical lavage samples was present only in HIV-coinfected women.40

In liver cells supporting HCV replication, negative-RNA strands were reported to be detected at a level 1 to 2 logs lower than the levels of positive strands.28,41 Our current study using a novel real-time quantitative PCR confirmed these findings with respect to liver, however, the ratio was lower in macrophages suggesting different replication dynamics in these cells. Infection of monocytes/macrophages by HCV is not unexpected, as these cells are known to be permissive to a wide range of viruses, including some other flaviviruses.42

In summary, our results suggest that HIV infection can facilitate extrahepatic replication of HCV in human macrophages. This could explain the phenomenon of relatively common presence of extrahepatic HCV replication in HIV-coinfected individuals.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, January 22, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2923.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant DA13760 and a grant from Palumbo Charitable Trust.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal