Abstract

The recent sequencing of a number of genomes has raised the level of opportunities for studies on proteins. This area of research has been described with the all-embracing term, proteomics. In proteomics, the use of mass spectrometric techniques enables genomic databases to be used to establish the identity of proteins with relatively little data, compared to the era before genome sequencing. The use of related analytical techniques also offers the opportunity to gain information on regulation, via posttranslational modification, and potential new diagnostic and prognostic indicators. Relative quantification of proteins and peptides in cellular and extracellular material remains a challenge for proteomics and mass spectrometry. This review presents an analysis of the present and future impact of these proteomic technologies with emphasis on relative quantification for hematologic research giving an appraisal of their potential benefits.

Proteomics: a definition

The fundamental role of proteins in supporting life was recognized in the early stages of biologic research. The name “protein,” derived from the Greek term, proteios, meaning “the first rank,” was used for the first time by Berzelius in 1838 to illustrate the importance of these molecules. The multivariate functions of specific cells, from movement to mitosis, are regulated by (very) approximately 9000 specialized protein types per nucleated cell. Posttranslational modifications (PTMs, such as sulfation, phosphorylation, farnesylation, hydroxylation, methylation, glycosylation)1 create microheterogeneity within a specific protein population, which adds to this complexity.

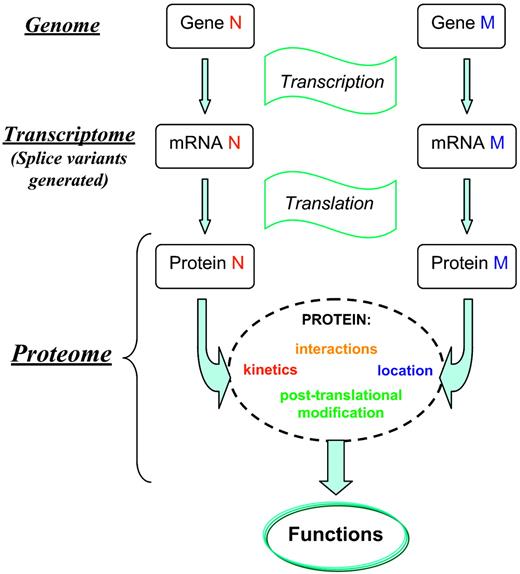

The array of proteins found within the cell, their interactions and modifications hold the key to understanding biologic systems. This is encapsulated in the term “proteome.” It can be defined as the protein population of a cell, characterized in terms of localization, PTM, interactions, and turnover, at any given time. The proteome is fundamentally dynamic and has an inherent complexity that surpasses that of the genome or the mRNA complement found within a cell (transcriptome; Figure 1). The development of DNA microarray technology allowed the analysis of gene expression at the mRNA level. Therefore, transcriptomics provides information about the degree of gene activity in individual tissues and the relationship to cell function, development stage, response to external stimuli, and disease.2,3 Although transcriptome data reflect the genome's objectives for protein synthesis, they do not provide information about the finalization of those objectives. Proteome analysis provides a view of biologic processes at their level of occurrence, thereby offering a better understanding of the physiologic and pathologic states of an organism, and becoming an important step in the development and validation of diagnostics and therapeutics. Studies of the correlation between transcriptome and proteome data have illustrated both satisfactory as well as poor correlations between the mRNA and protein concentration and turnover.4-6 The description of processes underlying hematopoietic cell development, leukemogenesis, and the functional activity of mature cells will be enhanced by application of proteomic approaches for protein characterization, study of protein-protein interaction, and, in particular, relative quantification. Here, the most effective and readily available techniques for relative sample analysis are described and their application to hematology explored.

Progression from genome to proteome. When a gene is expressed, the coding DNA strand is transcribed into an mRNA, which is edited by intron excision and the joining of exons. At the transcriptome level, the study of mRNA expression by a genome at a given time is routinely performed using microarray analysis.89 Proteins are synthesized and may undergo cotranslational and posttranslational modification processes that are often involved in the formation of the functionally active structure of the protein. A given mRNA sequence can give rise to more than one protein. This figure illustrates aspects of this process. Although some of the observed properties of an organism can be correlated with the activity of a single gene, most of the time these are determined by the joint action of many gene products. It is only at the proteome level that the gene exerts its “function.” The operation and the functions of a living cell are usually the result of proteome dynamics. Protein-protein interactions are often responsible for the regulation of cellular metabolism (enzymes), maintenance of architectural features (structural proteins), and transfer and processing of information (signal and regulatory proteins). Because proteome analysis provides a view of the biologic processes at their level of occurrence, proteomics offers a better understanding than genomics of cell cycle, cell death, development stage, cell function, and cellular responses to external stimuli and disease. Proteomics has become an important step in the development and validation of diagnostics and therapeutics.90

Progression from genome to proteome. When a gene is expressed, the coding DNA strand is transcribed into an mRNA, which is edited by intron excision and the joining of exons. At the transcriptome level, the study of mRNA expression by a genome at a given time is routinely performed using microarray analysis.89 Proteins are synthesized and may undergo cotranslational and posttranslational modification processes that are often involved in the formation of the functionally active structure of the protein. A given mRNA sequence can give rise to more than one protein. This figure illustrates aspects of this process. Although some of the observed properties of an organism can be correlated with the activity of a single gene, most of the time these are determined by the joint action of many gene products. It is only at the proteome level that the gene exerts its “function.” The operation and the functions of a living cell are usually the result of proteome dynamics. Protein-protein interactions are often responsible for the regulation of cellular metabolism (enzymes), maintenance of architectural features (structural proteins), and transfer and processing of information (signal and regulatory proteins). Because proteome analysis provides a view of the biologic processes at their level of occurrence, proteomics offers a better understanding than genomics of cell cycle, cell death, development stage, cell function, and cellular responses to external stimuli and disease. Proteomics has become an important step in the development and validation of diagnostics and therapeutics.90

Separation procedures and gel electrophoresis-based quantification for proteomics

Most techniques currently used in proteomics use a variety of fractionation and separation steps prior to analysis by mass spectrometry (MS). Sample preparation and fractionation (see Dreger7 and Huber et al8 ) are beyond the limits of this review, but their importance at different stages of a proteome study is not to be underestimated and some examples of commonly used techniques are introduced throughout this review. Sample fractionation can be performed according to compound type (see “PTM of proteins” and “SELDI-ToF MS and the search for disease markers”) or subcellular organelle localization (this section). Separation steps can be used at the protein level, as well as at the peptide level. Typical experiments include affinity separation methods, 1- or 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis, or 1- or 2-dimensional chromatographic separation.

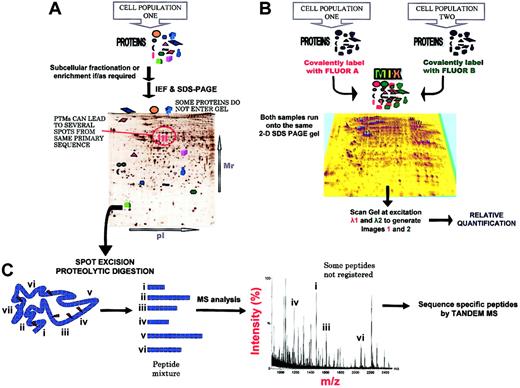

Two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2-DE) was initially described by O'Farrell in 1975 and has evolved markedly as one of the core technologies for the analysis of complex protein mixtures extracted from biologic samples. The proteins are separated in 2 steps according to 2 independent properties (isoelectric point [pI] and molecular weight [MW]). Görg and coworkers9 initiated the use of immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips for the first dimension of 2-DE (isoelectric focusing), increasing the reproducibility and resolution of the separation (Figure 2A).

The 2-DE gel-based methods in proteomics. (A) Most techniques currently used in proteomics involve the separation of the vast number of proteins present in a cell or tissue at a given time prior to analysis by MS and recognition and characterization using bioinformatics techniques. The protein separation can be performed at the protein or peptide level. One widespread methodology is 2-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2-D SDS-PAGE), which separates proteins according to their isoelectric points and molecular weights. One advantage of this approach is the ability to separate differentially posttranslationally modified forms of the same protein. A key disadvantage is that complete coverage of the proteome cannot be achieved, because some proteins will not enter the gel. Relative quantification of proteins between samples was in the past achieved by intergel comparisons following staining (Table 1). (B) The recently deployed technique of fluorescence 2-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis (2-D DIGE) for the relative quantification of proteins from up to 3 cell states on the same gel offers a greater reproducibility than previous approaches. Prior to the 2-D SDS-PAGE separation, the samples are covalently labeled with succinimidyl esters of different cyanide dyes (Cy2, Cy3, and Cy5). The N-hydroxy-succinimidyl esters undergo nucleophilic substitution reaction with the lysine ϵ amine groups to give an amide. The samples are then mixed together and separated on the same 2-D SDS-PAGE gel. The gel is scanned at the different excitation frequencies, the images merged, and the difference in protein abundance calculated. However, to maintain the solubility of the proteins during the electrophoretic separation, 2-D DIGE12 requires that only 1% to 2% of the lysine residues be derivatized (the derivatization increases the hydrophobicity of the proteins). Recently, a new set of dyes intended to fluorescently label all cysteine residues within a protein have been made available and these offer greater sensitivity.91 (C) Following separation, the protein spot is usually excised, subjected to in-gel enzymatic proteolysis, and analyzed by MS, usually MALDI-MS. The MALDI peptide fingerprint is often sufficient for confident protein recognition. For further confirmation, amino acid sequence information, or recognition of low-abundance proteins, tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis is performed, generally using electrospray (ES) ionization. A prevalent method that separates proteins at the peptide level is liquid chromatography (LC), usually used in conjunction with MS/MS (LC-MS/MS).

The 2-DE gel-based methods in proteomics. (A) Most techniques currently used in proteomics involve the separation of the vast number of proteins present in a cell or tissue at a given time prior to analysis by MS and recognition and characterization using bioinformatics techniques. The protein separation can be performed at the protein or peptide level. One widespread methodology is 2-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2-D SDS-PAGE), which separates proteins according to their isoelectric points and molecular weights. One advantage of this approach is the ability to separate differentially posttranslationally modified forms of the same protein. A key disadvantage is that complete coverage of the proteome cannot be achieved, because some proteins will not enter the gel. Relative quantification of proteins between samples was in the past achieved by intergel comparisons following staining (Table 1). (B) The recently deployed technique of fluorescence 2-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis (2-D DIGE) for the relative quantification of proteins from up to 3 cell states on the same gel offers a greater reproducibility than previous approaches. Prior to the 2-D SDS-PAGE separation, the samples are covalently labeled with succinimidyl esters of different cyanide dyes (Cy2, Cy3, and Cy5). The N-hydroxy-succinimidyl esters undergo nucleophilic substitution reaction with the lysine ϵ amine groups to give an amide. The samples are then mixed together and separated on the same 2-D SDS-PAGE gel. The gel is scanned at the different excitation frequencies, the images merged, and the difference in protein abundance calculated. However, to maintain the solubility of the proteins during the electrophoretic separation, 2-D DIGE12 requires that only 1% to 2% of the lysine residues be derivatized (the derivatization increases the hydrophobicity of the proteins). Recently, a new set of dyes intended to fluorescently label all cysteine residues within a protein have been made available and these offer greater sensitivity.91 (C) Following separation, the protein spot is usually excised, subjected to in-gel enzymatic proteolysis, and analyzed by MS, usually MALDI-MS. The MALDI peptide fingerprint is often sufficient for confident protein recognition. For further confirmation, amino acid sequence information, or recognition of low-abundance proteins, tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis is performed, generally using electrospray (ES) ionization. A prevalent method that separates proteins at the peptide level is liquid chromatography (LC), usually used in conjunction with MS/MS (LC-MS/MS).

Visualization methods for protein detection following 1-DE or 2-DE separation represent a critical step in quantitative proteome analysis.10 Methods available vary in limit of detection, dynamic range, and compatibility with analysis by MS (Table 1). Although autoradiography, following prelabeling of the cells with 35S or 32P, is the most sensitive detection method, with a wide dynamic range, this technique is restricted to living cells and is not suitable for tissue samples. Detection of proteins using fluorescence labeling, such as SYPRO Ruby,11 has gained increased popularity and offers a wide linear dynamic range, detection of nanogram amounts of protein, end-point staining times (staining times can be varied without overdeveloping) resulting in higher reproducibility, and has the advantage of not requiring viable cells capable of taking up radiolabeled chemicals. Equivalently, the use of succinimidyl esters of the fluorescent cyanide (Cy) dyes to label α amines of peptides and the ϵ amino groups of lysine residues on proteins prior to 2-DE is a welcome advance offering relatively good sensitivity. Fluorescent Cy3, Cy5, or Cy2 dye-prelabeled protein samples can all be run on the same 2-DE gel, allowing for intragel relative quantification of proteins from 2 or 3 preparations, a technique known as difference in-gel electrophoresis or DIGE12 (Figure 2B). We have used this approach with chronic myeloid leukemia CD34+ cells using 1 × 106 cells/sample, visualizing approximately 1000 protein spots per 2-DE gel. This cell population (> 95% CD34+) gave intersample variation in spot patterns (< 5% of total spot number) in 6 samples analyzed. Changes of as little as 30% in protein expression levels could be reproducibly detected (S. Griffiths, C. A. Evans, and A.D.W., unpublished observations, August 2003), offering a sensitive means of detecting proteomic changes. The DIGE approach provides an instrumentally undemanding alternative to methods that use differential stable isotope labeling and can be coupled to on-line liquid chromatographytandem MS for the detection of drug or growth factor effects on specific proteins in cells.13 A new cyanide dye derivative that labels cysteine residues has now been produced and offers enhanced sensitivity12 (Table 1); the effect of variable cysteine content of different protein types must, however, be noted.

Methods of protein detection for gel-based proteomics

Visualization method . | Limit of detection, ng . | Dynamic range . | Detection . | No. of samples/gel . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colloidal Coomassie blue | 8-10 | 20-fold | Densitometry | 1 | Compatible with analysis by MS. |

| Linear response restricted to high ng amounts of protein | This method, which uses tricholoroacetic acid and alcohol in the staining solution, results in esterification of aspartic and glutamic side chain carboxyl groups, complicating the interpretation of the mass spectra. | ||||

| Silver | 2-10 | 8-to 10-fold | Densitometry | 1 | Some protocols compatible with analysis by MS. |

| Linear response restricted to low ng amounts of protein | Staining times and reaction temperatures are critical for reproducibility. | ||||

| Zinc-imidazole | 5-10 | Linear response restricted to high ng to μg amounts of protein | Densitometry | 1 | Compatible with analysis by MS. |

| Reverse staining allows higher protein recovery. | |||||

| Rapid (5-15 minutes). | |||||

| Sample overloading decreases the capacity of distinguishing between different bands (1-DE) or spots (2-DE). | |||||

| Cy3, Cy5 | 5-10 | 1000-fold | Fluorescent | 2-3 | Compatible with analysis by MS. |

| Linear response on wide range | Allows for both intragel and intergel relative quantification of protein spots from samples. | ||||

| SYPRO Ruby | 1-8 | 1000-fold | Fluorescent | 1 | Compatible with analysis by MS. |

| Linear response on wide range | Rapid. | ||||

| Staining time is not critical and can be varied from experiment to experiment without overdeveloping. |

Visualization method . | Limit of detection, ng . | Dynamic range . | Detection . | No. of samples/gel . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colloidal Coomassie blue | 8-10 | 20-fold | Densitometry | 1 | Compatible with analysis by MS. |

| Linear response restricted to high ng amounts of protein | This method, which uses tricholoroacetic acid and alcohol in the staining solution, results in esterification of aspartic and glutamic side chain carboxyl groups, complicating the interpretation of the mass spectra. | ||||

| Silver | 2-10 | 8-to 10-fold | Densitometry | 1 | Some protocols compatible with analysis by MS. |

| Linear response restricted to low ng amounts of protein | Staining times and reaction temperatures are critical for reproducibility. | ||||

| Zinc-imidazole | 5-10 | Linear response restricted to high ng to μg amounts of protein | Densitometry | 1 | Compatible with analysis by MS. |

| Reverse staining allows higher protein recovery. | |||||

| Rapid (5-15 minutes). | |||||

| Sample overloading decreases the capacity of distinguishing between different bands (1-DE) or spots (2-DE). | |||||

| Cy3, Cy5 | 5-10 | 1000-fold | Fluorescent | 2-3 | Compatible with analysis by MS. |

| Linear response on wide range | Allows for both intragel and intergel relative quantification of protein spots from samples. | ||||

| SYPRO Ruby | 1-8 | 1000-fold | Fluorescent | 1 | Compatible with analysis by MS. |

| Linear response on wide range | Rapid. | ||||

| Staining time is not critical and can be varied from experiment to experiment without overdeveloping. |

For proteome analysis, the most important criteria to be considered when evaluating methods of protein detection are limit of detection, dynamic range, homogeneity, and compatibility with MS analysis. The properties of some of the commonly techniques are shown. Most proteomics studies require limits of detection in the low nanogram protein range, which would correspond to the femtomole levels usually detectable by MS analysis (eg, 1-20 ng, corresponding to 100 fmol of a 10-200 kDa protein). A wide linear dynamic range is essential when the aim of the study is relative quantification between samples. The homogeneity of the detection refers to the uniformity of staining between different classes of proteins. When the method targets only one amino acid, proteins that do not contain that particular residue are not detected (eg, cysteine). An ideal detection method would target all amino acid residues equally, so that the signal detected would be directly proportional to the length of the amino acid chain. The compatibility of the method of detection with MS analysis is particularly important for the recognition of the proteins. The presence of formaldehyde or glutaraldehyde in various solutions used for silver staining (fixing, silver impregnation, and developing) interferes with protein recognition because these aldehydes alkylate the α and ϵ amino groups of proteins.10 Silver staining methods compatible with MS analysis were developed by removing the glutaraldehyde and decreasing the use of formaldehyde in the stain.99 Although most detection methods allow only intergel comparison, the new generation of cyanide dyes that chemically modify lysine or cysteine residues offer the potential for multiplexing in gel-based experiments (see “Separation procedures and gel electrophoresis-based quantification for proteomics” and Figure 2) while not compromising downstream MS analysis. Regardless of the detection method, the principal method for relative quantification is densitometry analysis. Providing that there is a good reproducibility between the 2-DE protein patterns, densitometry is an important tool in proteome analysis because it allows the simultaneous detection and quantification of hundreds of proteins from a multitude of cell states. A number of computer-assisted image analysis software packages that allow the comparison of 2-DE protein patterns, such as PDQuest (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), Melanie (Bio-Rad), and Progenesis (Non-linear Dynamics, Durham, NC), are now commercially available. However, the technique suffers from a number of limitations, either inherited from 2-DE's lack of reproducibility and poor dynamic range of staining methods, or, depending on which software is used for the analysis, from its own poor sensitivity of detection. New software and methods constantly improve protein detection and image warping, but the success of the matching still depends extensively on the similarity of the protein patterns. For in-gel comparison, DIGE experiments plus the appropriate analytical software therefore offer an effective way forward in relative quantification of the hundreds of proteins found in 2-DE gel experiments.

Despite these advances, the use of 2-DE still remains an object of debate concerning its value in proteomics research. Detractors argue it is cumbersome, time-consuming, and lacking in automation, whereas to others it remains an efficient way to separate complex protein mixtures. Issues of reproducibility, sensitivity, and protein losses during extraction for MS analysis have precluded its wider acceptance.9 The undisputed need for replicate studies (at least 3 replicate studies per sample) for the assessment of reproducibility of protein pattern and relative quantity adds to the time necessary for the assessment and interpretation of data. Nonetheless, software available for relative 2-DE spot pattern analysis is sufficiently sophisticated to allow relative quantification from DIGE or other experiments (Figure 2 and Table 1, respectively). Using such software, 2-DE gels can be used to identify significant differences between patient samples, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with mutated and unmutated immunoglobulin heavy-chain loci, respectively.14 Use of 2-DE can separate the thousands of plasma or serum proteins, including posttranslational variants of some proteins. The requirement for higher resolution separation can be achieved using several 2-DE gels with overlapping narrow pH gradients that reduce the presence of multiple proteins per spot, such as differentially posttranslationally modified proteins.15 The use of narrow IPGs also allows for an increased loading capacity, and therefore improves the detection of low-abundance proteins. A concerted effort to map the human plasma proteome (including the 2-DE approach) is now underway in the belief that further proteins of diagnostic and therapeutic value will be identified.16

Further application of gel-based technologies in hematology can be seen in a variety of different studies.17,18 Prelabeling cells with 32P has been used to recognize proteins phosphorylated as a consequence of cytokine action.19 No assumptions are made about the phosphorylated proteins prior to identification. For example, 25 new substrates for mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase have been recognized using an approach based on 2-DE.20 Recently, a fluorescent dye that reversibly associates with phosphorylated proteins within gels has been characterized.21 Preliminary experiments in our laboratory (C. A. Evans, R. Unwin, unpublished observations, July 2003) indicate that it does have value as an initial screen for agonist-stimulated phosphorylation events in hematopoietic cells, obviating the need for prelabeling and opening the possibility of performing such studies on freshly isolated primary cells. The sensitivity and specificity of the technique, however, will be key issues. The experimental simplicity of this technique contrasts with alternative strategies such as the more quantitatively rigorous approach taken by Mann's group to signal transduction proteomics.22 Untreated HeLa cells, grown in medium containing [12C]-arginine, were mixed with cells treated with epidermal growth factor (EGF) after culture in [13C]-arginine–containing medium. A total of 28 proteins that selectively bind the SH2 domain of the adaptor protein Grb2 were recognized using affinity purification, followed by liquid chromatography (LC) separation and analysis by MS. The levels of the proteins from the 2 samples were compared using the inherent isotope coding of all the proteins (see “MS-based quantitative proteomics”). This metabolically stable isotope-labeling technique can, in theory, be applied to any mammalian cell line under 2 different conditions. It therefore lends itself to the study of hematopoiesis.

Using 2-DE gels and standard staining methods, myeloid cell development can be followed in terms of multiple quantitative changes in protein composition.6 Similarly, determination of the change in the proteome of lymphocytes as they prepare for antibody production provides an elegant example of the application of 2-DE to a specific research issue.23 Cells were shown to increase expression of metabolic enzymes and endoplasmic reticulum components sequentially, prior to engaging on the generation of their secretory product. This study illustrates the value of proteomics methods in generating a single multifaceted picture of cellular events, providing prompts for more detailed investigations. A 2-DE proteomics approach was also used for the identification of potential markers for lymphoma classification, eosinophil activation, and recognition of isoforms of proteins involved in apoptotic suppression.24-27

These studies focused on the proteome assay of whole-cell lysates. There is a growing recognition that prefractionation of the sample offers substantial analytical advantages.7,8 Removal of highly expressed proteins presents opportunities for increasing dynamic range and thereby improving the detection of proteins expressed at lower levels. Thus, an important advance, increasing the prospect of protein identification in organelles, is subcellular fractionation. Studies on enriched organelles allow the identification of proteins with no previously recognized organellar function.28,29 With respect to hematopoietic cells, phagosomes have been isolated from macrophages and over 140 proteins recognized in a 2-DE/MS study.30,31 Localization of proteins using techniques such as green fluorescent protein tagging and high-resolution imaging confirm that this is a robust method for assigning proteins within complexes or organelles; this approach to organelle analysis is fully reviewed by Dreger.7 By extension, relative quantification of low-abundance proteins will be achieved more effectively using prefractionation techniques. Nonetheless, any such study is limited by the failure of some hydrophobic, large, or basic proteins to enter 2-DE gels.

A nonquantitative approach to identification of such proteins within biologic material is exemplified by the work of Link et al32 who submitted a protein complex directly to enzymatic digestion and characterized the resulting complex mixture of peptides by 2-dimensional chromatographic (strong cation exchange–reversed phase) separation and electrospray-tandem MS (ES-MS/MS) analysis (see next section). The resulting product ion spectra were automatically correlated with predicted amino acid sequences in translated genomic databases. This method was further developed by the same group33 to achieve full automation. The technique, termed multidimensional protein identification technology (Mud-Pit), involves not only the separation of peptide mixtures but direct MS analysis and database searching. This study achieved in a single experiment a much higher number of detected and recognized proteins than with a 2-DE study. This large-scale identification, loosely termed “shotgun” proteomics, has a throughput higher than 2-DE/MS approaches and can deliver high-quality data but requires sophisticated and automated LC-MS/MS apparatus and an acceptance that few conclusions can be drawn on the amount of any protein/peptide found in the sample.

Protein recognition using MS

The recent advances in proteomics were mainly driven by the increasing ability of MS to detect and characterize low levels of proteins. MS-based proteomics has a growing role in biomedical research where limited sample material is available, as femtomole sensitivity is routinely achieved.34 In hematology, MS has been used for protein, peptide, and DNA sequencing,6 protein-folding studies, noncovalent interaction analysis, analysis of PTMs,35 identification of novel proteins,36 and in a variety of diagnostic and drug discovery projects.16,37-40

The main components of a mass spectrometer are an ion source, one or several mass analyzers, and a detector.34 Electrospray (ES; Figure 3B) and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI; Figure 3A) processes provide “soft” (meaning low-energy) ionization methods for a variety of biomolecules, including peptides, proteins, drug metabolites, oligonucleotides, and carbohydrates, to enable their measurement by MS. There are several types of commercially available mass spectrometers that combine ES or MALDI with a variety of mass analyzers. In simple terms, gas-phase ions, produced in the ion source, are introduced into the mass analyzer and differentiated according to their mass/charge (m/z) ratio on the basis of their motion in a vacuum under the influence of electric or magnetic fields. Figure 2C illustrates a typical experiment in which the identity of a protein from a 2-DE gel can be discerned using peptide mass fingerprinting by MALDI time-of-flight (ToF) MS, or tandem MS (MS/MS).

MS instrumentation used in proteomics. The fundamental principle of MS analysis involves the conversion of the subject molecules to either cations or anions in the ion source, separation according to their mass/charge (m/z) ratios in the mass analyzer, and subsequent detection. Several configurations of mass spectrometers that combine ES and MALDI with a variety of mass analyzers (linear quadrupole mass filter [Q], time-of-flight [ToF], quadrupole ion trap, and Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance [FTICR] instrument) are routinely used. (A) In MALDI, the sample is embedded in a large excess of a matrix that has a strong absorption at the laser wavelength. Following the laser irradiation of the sample surface, the matrix accumulates a large amount of energy that is thought to initiate the proton transfer between the matrix and the analyte compound to form ions. The ions observed during MALDI MS are mainly singly charged. This results in simple spectra (because the m/z ratio is what is being measured) even in the case of analysis of mixtures but can be a disadvantage for peptide sequencing, which requires the achievement of peptide fragmentation, a process that preferentially occurs with multicharged peptides. The concurrent and independent development of ToF mass analyzer and its compatibility with this ionization method resulted in the rapid development of MALDI-ToF as a routine analytical mass spectrometer.92 Other configurations, however, have also been successfully applied for the analysis of peptides and proteins, such as MALDI-ion trap,50 MALDI-QqToF52 (where q represents a quadrupole ion decomposition region), and MALDI-ToF-ToF.51 This type of ionization method is also used in SELDI-ToF MS. (B) ES is a continuous nebulization process that produces ions directly from solution and facilitates interfacing of LC with MS. A sample is passed with flow rates of 1 to 10 μL/min through a capillary held at high potential relative to ground and counter electrode. The strong electric field obtained induces charge accumulation at the liquid surface situated at the end of the capillary and leads to the formation of a mist of highly charged droplets. The ES process results in the formation of multiply charged ions. This is one of the principal advantages of this method because it allows the analysis of ions from high-molecular-mass molecules, such as proteins and peptides, using mass spectrometers of limited m/z ratio range. (C) The quadrupole analyzer is frequently termed a mass filter because it transmits only ions within a narrow m/z range. The analyzer uses the stability of the trajectory to separate these ions according to their m/z ratio. The stability of the oscillating trajectories of the ions is based on the joint application of direct current and radio-frequency voltages on 4 parallel cylindrical metal rods. (D) Unlike the scanning devices such as quadrupoles, ToF analyzers separate ions temporally rather than spatially. The ions are rapidly accelerated into a “field-free” drift region also called a “flight tube,” and their separation is achieved by measuring the difference in transit time from the ion source to the detector. The reflectron, which consists of a series of rings or grids that act as an ion mirror, compensates for the initial kinetic energy distributions of ions. (E) The ion trap analyzer captures the ions, which collide with the helium “bath” gas and start to oscillate in a predicted motion. Ion trap can be used as a “tandem-in-time” instrument as selection, fragmentation, and analysis of ions take place in the same space. Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer (FTICR; not illustrated) is also a trapping device, in this case by using strong magnetic fields, and offers great opportunities for investigating protein interactions and PTMs, with high sensitivity, mass accuracy, and resolution.93

MS instrumentation used in proteomics. The fundamental principle of MS analysis involves the conversion of the subject molecules to either cations or anions in the ion source, separation according to their mass/charge (m/z) ratios in the mass analyzer, and subsequent detection. Several configurations of mass spectrometers that combine ES and MALDI with a variety of mass analyzers (linear quadrupole mass filter [Q], time-of-flight [ToF], quadrupole ion trap, and Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance [FTICR] instrument) are routinely used. (A) In MALDI, the sample is embedded in a large excess of a matrix that has a strong absorption at the laser wavelength. Following the laser irradiation of the sample surface, the matrix accumulates a large amount of energy that is thought to initiate the proton transfer between the matrix and the analyte compound to form ions. The ions observed during MALDI MS are mainly singly charged. This results in simple spectra (because the m/z ratio is what is being measured) even in the case of analysis of mixtures but can be a disadvantage for peptide sequencing, which requires the achievement of peptide fragmentation, a process that preferentially occurs with multicharged peptides. The concurrent and independent development of ToF mass analyzer and its compatibility with this ionization method resulted in the rapid development of MALDI-ToF as a routine analytical mass spectrometer.92 Other configurations, however, have also been successfully applied for the analysis of peptides and proteins, such as MALDI-ion trap,50 MALDI-QqToF52 (where q represents a quadrupole ion decomposition region), and MALDI-ToF-ToF.51 This type of ionization method is also used in SELDI-ToF MS. (B) ES is a continuous nebulization process that produces ions directly from solution and facilitates interfacing of LC with MS. A sample is passed with flow rates of 1 to 10 μL/min through a capillary held at high potential relative to ground and counter electrode. The strong electric field obtained induces charge accumulation at the liquid surface situated at the end of the capillary and leads to the formation of a mist of highly charged droplets. The ES process results in the formation of multiply charged ions. This is one of the principal advantages of this method because it allows the analysis of ions from high-molecular-mass molecules, such as proteins and peptides, using mass spectrometers of limited m/z ratio range. (C) The quadrupole analyzer is frequently termed a mass filter because it transmits only ions within a narrow m/z range. The analyzer uses the stability of the trajectory to separate these ions according to their m/z ratio. The stability of the oscillating trajectories of the ions is based on the joint application of direct current and radio-frequency voltages on 4 parallel cylindrical metal rods. (D) Unlike the scanning devices such as quadrupoles, ToF analyzers separate ions temporally rather than spatially. The ions are rapidly accelerated into a “field-free” drift region also called a “flight tube,” and their separation is achieved by measuring the difference in transit time from the ion source to the detector. The reflectron, which consists of a series of rings or grids that act as an ion mirror, compensates for the initial kinetic energy distributions of ions. (E) The ion trap analyzer captures the ions, which collide with the helium “bath” gas and start to oscillate in a predicted motion. Ion trap can be used as a “tandem-in-time” instrument as selection, fragmentation, and analysis of ions take place in the same space. Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer (FTICR; not illustrated) is also a trapping device, in this case by using strong magnetic fields, and offers great opportunities for investigating protein interactions and PTMs, with high sensitivity, mass accuracy, and resolution.93

SELDI-ToF MS and the search for disease markers

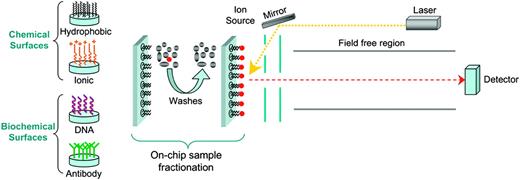

The technique (Figure 4) has at its heart a means of enriching for proteins with certain chemical characteristics that determine their interaction with a set of specific surfaces used as a laser desorption ionization target.41 As such, it is often cited as an array technology (see “Protein arrays”). Unlike other MS-based strategies (Figure 2), the SELDI approach does not generally include enzymatic digestion of proteins, so that detection of intact (generally small) proteins is involved. One advantage of this chip-based technique is that crude samples can readily and rapidly be analyzed with high throughput. The key disadvantage is that the mass spectrum obtained does not enable identification of the proteins analyzed and further work is therefore required. The obtained data are analyzed to recognize critical features that may be used as markers for diagnosis or prognosis. In a landmark study, a training set of serum SELDI-ToF spectra from 50 unaffected women and 50 patients with ovarian cancer was analyzed by an iterative algorithm that identified a proteomic pattern to discriminate healthy patients from those with malignant disease, using the minimum amount of information.42 A similar study on prostate cancer and lung cancer reveals the general applicability of this technique.43,44 Furthermore, there are indications that determination of a serum protein level (eg, high-density lipoproteins) can be monitored effectively and straightforwardly with SELDI-ToF MS45 and therefore, indicators of hematologic disease could theoretically be measured in the same fashion. In an adaptation of the technique thin slices of solid tumors are also being used as targets for MALDI-ToF MS. The application of this mass spectrometric approach hopefully will deliver a raft of new clinical indicators and surrogate markers for response. A considerable effort, initiated by Caprioli and coworkers, has been applied for the direct analysis of tissue slices by MALDI MS.46 More recent work, such as the study of non–small-cell lung tumors,47 showed the potential of this technique for the detection of disease markers.

Principle of surface-enhanced laser desorption ionization (SELDI)–ToF MS. This is a technique for the enrichment of proteins with specific chemical characteristics and combines chromatography with MS. ProteinChip arrays have been designed that contain chemically or biochemically treated surfaces. The sample, consisting of crude extracts or mixtures of whole proteins, is applied to the surface. After a series of washes, the targeted proteins are selectively retained. An energy-absorbing solution is added to the surface and the sample is subjected to laser desorption ionization. The formed ions are measured using a ToF mass analyzer as previously described. Characteristic features of spectra can be used for prognostic purposes (“SELDI-ToF MS and the search for disease markers”).

Principle of surface-enhanced laser desorption ionization (SELDI)–ToF MS. This is a technique for the enrichment of proteins with specific chemical characteristics and combines chromatography with MS. ProteinChip arrays have been designed that contain chemically or biochemically treated surfaces. The sample, consisting of crude extracts or mixtures of whole proteins, is applied to the surface. After a series of washes, the targeted proteins are selectively retained. An energy-absorbing solution is added to the surface and the sample is subjected to laser desorption ionization. The formed ions are measured using a ToF mass analyzer as previously described. Characteristic features of spectra can be used for prognostic purposes (“SELDI-ToF MS and the search for disease markers”).

Sequence analysis of peptides and proteins using MS

Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) allows for protein and peptide sequencing and has therefore evolved as an indispensable tool for protein recognition, structure elucidation, and characterization of PTMs. Figure 5 shows examples of ES Q-ToF MS/MS analyses of peptides for amino acid sequence information (A) and detection of site of phosphorylation (B). Sequence analysis of peptides by collision-induced dissociation (CID) during MS/MS48 is a favorable alternative to the classical sequencing performed by the Edman degradation technique.49 In contrast to Edman degradation, which remains valuable for N-terminal sequencing of large amounts of relatively pure peptides, MS/MS analysis can be used for the sequencing of peptides present in mixtures or blocked at the N-terminus of the sequence. The recent advances in coupling a MALDI ion source to ion trap,50 ToF/ToF,51 and Q-ToF52 mass spectrometers provide enhanced opportunities for high-throughput analyses.

Sequencing of peptides using MS/MS. Peptide fragmentation by collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) during MS/MS48 allows the recognition of complete or partial peptide sequence. Following collisional activation, the peptides undergo fragmentation along the backbone or in their side chains giving rise to product ions that can be attributed to the amino acid sequence. The nomenclature for classifying these ions allows the labeling of all the various fragment ions. The 3 possible cleavage points of the peptide backbone are called an,bn, and cn when the charge is retained at the N-terminal fragment of the peptide, and xm,ym, and zm when the charge is retained by the C-terminal fragment. The subscripts n and m indicate which amide bond is cleaved counting from the N- and C-terminus, respectively, and thus also the number of amino acid residues contained by the fragment ion. Immonium ions and internal fragments are usually labeled with the letter codes of the amino acids (not indicated in this figure). Product ions derived from fragmentation at the side chain of the peptide (labeled d, v, and w) are not discussed here. Panel A illustrates the ES Q-ToF product ion spectrum of [M+2H]2+ at 768 m/z, corresponding to fibrinogen αA from rat hepatocytes, following digestion with trypsin, where [M+2H]2+ denotes the doubly charged precursor ion selected for fragmentation. An almost complete series of b and y ions was obtained in this analysis resulting in a facile identification of the peptide sequence. Panel B illustrates the application of MS/MS analysis for the search for sites of phosphorylation. The product ion spectrum, recorded in positive mode, was obtained from the 1-dimensional liquid chromatography-tandem electrospray mass spectrometry analysis (LC-MS/MS) of a phosphorylated peptide. The signals between 1200 and 2000 m/z are magnified by a factor of 2.5. The sites of phosphorylation are searched by scanning for loss of phosphate or for characteristic immonium ions (Figure 7). [M+2H]2+ denotes the doubly charged precursor ion selected for fragmentation, and the [M+2H]2+-H3PO4 denotes the characteristic loss of the phosphate moiety from the precursor ion.

Sequencing of peptides using MS/MS. Peptide fragmentation by collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) during MS/MS48 allows the recognition of complete or partial peptide sequence. Following collisional activation, the peptides undergo fragmentation along the backbone or in their side chains giving rise to product ions that can be attributed to the amino acid sequence. The nomenclature for classifying these ions allows the labeling of all the various fragment ions. The 3 possible cleavage points of the peptide backbone are called an,bn, and cn when the charge is retained at the N-terminal fragment of the peptide, and xm,ym, and zm when the charge is retained by the C-terminal fragment. The subscripts n and m indicate which amide bond is cleaved counting from the N- and C-terminus, respectively, and thus also the number of amino acid residues contained by the fragment ion. Immonium ions and internal fragments are usually labeled with the letter codes of the amino acids (not indicated in this figure). Product ions derived from fragmentation at the side chain of the peptide (labeled d, v, and w) are not discussed here. Panel A illustrates the ES Q-ToF product ion spectrum of [M+2H]2+ at 768 m/z, corresponding to fibrinogen αA from rat hepatocytes, following digestion with trypsin, where [M+2H]2+ denotes the doubly charged precursor ion selected for fragmentation. An almost complete series of b and y ions was obtained in this analysis resulting in a facile identification of the peptide sequence. Panel B illustrates the application of MS/MS analysis for the search for sites of phosphorylation. The product ion spectrum, recorded in positive mode, was obtained from the 1-dimensional liquid chromatography-tandem electrospray mass spectrometry analysis (LC-MS/MS) of a phosphorylated peptide. The signals between 1200 and 2000 m/z are magnified by a factor of 2.5. The sites of phosphorylation are searched by scanning for loss of phosphate or for characteristic immonium ions (Figure 7). [M+2H]2+ denotes the doubly charged precursor ion selected for fragmentation, and the [M+2H]2+-H3PO4 denotes the characteristic loss of the phosphate moiety from the precursor ion.

The development of computer algorithms that can correlate the data obtained from MS and MS/MS analyses with databases enables one to use either peptide mass fingerprint information or MS/MS CID data to recognize a protein.53,54 Recently developed algorithms allow the search of uninterpreted or partially interpreted MS/MS spectra,55,56 for example, SEQUEST,55 Mascot, PepFrag, Sonar, XProteo, and MS-Tag. The programs search for all peptides present in databases that have the same mass as the precursor ion selected by the user, predict the principal fragment ions that would be expected for these database peptides, and then match these with the experimental data. In this way the original peptide can be identified in terms of amino acid sequence and the protein from which it originated deduced. The confidence in the result obtained can be increased using a variety of peptide derivatization methods57,58 designed to obtain a specific set of parameters to be included in the algorithms for database search, which would reduce the ambiguity of the sequence.

MS-based quantitative proteomics

The methods most commonly used for quantitative proteome analysis are relative quantification methods.59 Although densitometry or fluorescent analysis of spot intensity following 2-DE gel staining have an important niche in cell biology, a more versatile technique for precise relative quantification involves the differential labeling of each set of proteins or peptides derived from 2 different cell states with light and heavy isotopes of the same chemical reagent and subsequent MS analysis59,60 (Figure 6). This approach allows for relative quantification of basic, hydrophobic, or large proteins excluded from analysis using 2-DE or DIGE. Two derivatized samples are combined and analyzed by MS, which allows the calculation of the relative abundance levels of the proteins. This method is based on the assumption that the structurally similar isotopically labeled peptides have identical ionization efficiencies during the mass spectrometric analysis. The light- and heavy-labeled peptides appear in the mass spectrum as doublets, and the peak heights illustrate the relative abundance of the protein in each cell state. In MS the intensity of a specific peptide signal is dependent on the chemical and physical properties of the analyte, the associated solvent, and other factors. The signals from 2 peptides, even from the same protein, will therefore differ in intensity. Only the use of a direct comparison of chemically similar entities can yield relative quantification. The isotopic labels can be incorporated either during cell culture,61,62 or at the protein or peptide level.

Isotopic labeling for relative quantification using MS. Proteins or peptides derived from 2 different cell states are derivatized with light and heavy isotopes of the same chemical reagent. The samples are then combined and analyzed by MS. The relative abundance levels of the proteins are calculated by comparing the peak heights of the light- and heavy-labeled peptides. The isotopic label can be incorporated in vivo, in vitro, at the protein, or at the peptide level. In cell culture, the incorporation was achieved by using media that included the isototopic labels, such as 15N or 14N media, minimal medium, or minimal medium with isotopically labeled leucine (leuD10).61,62,94,95 The stable isotope-labeling approach has also been used for detecting the numbers of the tagged amino acid residues and, therefore, for unambiguously recognition of the protein.62,95 A method that gained increased popularity is the isotope-coded affinity tag (ICAT) approach.13 The label contains a thiol group (which reacts with cysteine residues), 8 hydrogens (light) or deuteriums (heavy), used for relative quantification, and a biotin group that is selectively recognized during the affinity extraction step by an avidin moiety attached to the chromatographic column. Proteins from 2 cell states are derivatized with either the heavy or the light isotope and the mixture is digested and separated by affinity extraction prior to tandem mass spectrometric analysis. The ICAT analysis with the initial reagent used was complicated by the fact that heavy-labeled peptides elute earlier than the light-labeled peptides during LC separation, the so-called deuterium effect.96 Newer cleavable 13C-labeled ICAT reagents have significant advantages over the original reagents.97

Isotopic labeling for relative quantification using MS. Proteins or peptides derived from 2 different cell states are derivatized with light and heavy isotopes of the same chemical reagent. The samples are then combined and analyzed by MS. The relative abundance levels of the proteins are calculated by comparing the peak heights of the light- and heavy-labeled peptides. The isotopic label can be incorporated in vivo, in vitro, at the protein, or at the peptide level. In cell culture, the incorporation was achieved by using media that included the isototopic labels, such as 15N or 14N media, minimal medium, or minimal medium with isotopically labeled leucine (leuD10).61,62,94,95 The stable isotope-labeling approach has also been used for detecting the numbers of the tagged amino acid residues and, therefore, for unambiguously recognition of the protein.62,95 A method that gained increased popularity is the isotope-coded affinity tag (ICAT) approach.13 The label contains a thiol group (which reacts with cysteine residues), 8 hydrogens (light) or deuteriums (heavy), used for relative quantification, and a biotin group that is selectively recognized during the affinity extraction step by an avidin moiety attached to the chromatographic column. Proteins from 2 cell states are derivatized with either the heavy or the light isotope and the mixture is digested and separated by affinity extraction prior to tandem mass spectrometric analysis. The ICAT analysis with the initial reagent used was complicated by the fact that heavy-labeled peptides elute earlier than the light-labeled peptides during LC separation, the so-called deuterium effect.96 Newer cleavable 13C-labeled ICAT reagents have significant advantages over the original reagents.97

In our laboratory, we have used guanidination with [14N]-and [15N]-O methylisourea for a combined increased sensitivity of detection of lysine C-terminus peptides, relative quantification of 2 cell states, and de novo sequencing.63 The 2-Da mass difference between the light and heavy isotope-labeled peptides allows for simultaneous selection and fragmentation of both isotopomers during MS/MS and assignment of C-terminus fragments is therefore readily achieved by virtue of their presence as doublets in the product ion spectra. Alternatively, the differential derivatization can be followed by an enrichment step prior to the analysis by MS. Enzymatic digestion of proteins with either

Although it is sometimes suggested that ICAT frees one from the constraints of the lesser technology of 2-DE, a recent study comparing ICAT and 2-DE demonstrated that neither offers comprehensive coverage of a proteome.66 A full evaluation of the relative quantification offered by these 2 techniques is required and we are presently undertaking such a study. The use of an ICAT approach for the identification and characterization of 491 microsomal proteins and determination of changes in expression during development of the promyelocytic cell line HL-60 demonstrates the power of this technique, especially because many of the proteins identified were hydrophobic. Nonetheless, such studies are not a casual undertaking.60 A paradigm study on the leukemogenic oncogene product Myc by Shiio et al67 shows the broad effects of a single protein on pathways as diverse as motile control and protein synthesis.

Recently, methods that use synthetic peptides, designed to mimic some of the naturally occurring peptides following the enzymatic digestion of the proteins of interest, have been developed for absolute quantification of proteins.68,69 The synthetic peptide, labeled with a stable isotope, is mixed with the sample prior to enzymatic digestion and analysis by LC-MS/MS. The peptide can be synthesized to contain a variety of modifications (such as phosphorylation) to allow quantification of PTMs. This will be a key aid in future pharmacokinetic studies and more generally in studies on signal transduction and other aspects of cell studies requiring absolute quantification.

Protein arrays

Abundant proteins can obscure the quantification of lower abundance proteins, such as signaling molecules or kinases. This problem can be reduced using ICAT and MudPit or prefractionation prior to 2-DE.28-30,70 Protein microarrays offer a different solution and have the potential for high-throughput applications to identify novel drug targets and disease markers and a sensitivity born of new technical approaches. The sequencing projects offer opportunities to manufacture protein chips that embrace the thousands of proteins encoded in the genome. Zhu et al in a landmark paper71 used gene tagging for enrichment of thousands of proteins from yeast to create a protein array and used this to screen for calmodulin- and phospholipid-binding proteins. This study is but one in which key issues of the appropriate surface for protein attachment, the maintenance of native protein folding, and the methods of detection for interacting agents have been addressed. Exciting advances include application of planar waveguide technology with which the measurement of as few as 500 cytokine molecules can be achieved,72 as reviewed by Mitchell.73 Advances in surface chemistry, microfluidics, and detection techniques will make rapid analysis of proteins in samples a reality in the future.74,75

Protein array technologies using discrete sets of known proteins are plainly of potential value in diagnostic or prognostic testing. A microarray of 60 antibodies has already been constructed for cluster of differentiation (CD) antigens by binding antibodies to a nitrocellulose-coated glass slide. The results achieved with this antibody array compared well with flow cytometric assessment of CD expression on a number of leukemic cell types and normal leukocytes.76 One strength of this approach is the relatively high number of markers that can be assayed per experiment compared to flow cytometry. However, discrete binding to subsets of cells is not easily assessed. The creation of high-density antibody microarrays using phage display technology and other methods, reviewed by Hebestreit,77 remains a realistic proposition for the characterization of the proteome. Development of appropriate arrays for concerted proteomics research projects will continue and, in the future, simultaneous measurement of many proteins from limited volumes of samples of complex biologic mixtures (such as serum or cell lysates) will be possible. Similarly, proteins can be arrayed to search for interacting partners. For example, Procognia (Maidenhead, Berkshire, United Kingdom) has arrayed p53 proteins with germline single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), or functional potassium regulatory channels; these arrays identify drug binding and effects on proteins.

Other approaches are being derived for global analysis of protein function and these include activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) for enzymes such as tyrosine phosphatases using selective modification of specific enzymatic active sites.78 Aptamers, which are single-stranded oligonucleotides that bind to proteins of interest, also offer a route to array-based techniques, for example, in protein quantification. Directed evolutionary chemistry processes using systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) identify aptamers by starting with a combinatorial library and the protein of interest (tethered to an appropriate substratum), a repetitive process,79 which leads to the creation of a DNA or RNA molecule with a high affinity for a specific protein. There may be therapeutic potential; for example, a thrombin aptamer may have clinical value as an anticoagulant.80 Somalogic (Boulder, CO) has developed aptamer based protein arrays for the measurement of thousands of proteins from a single sample.

PTM of proteins

Following synthesis, the protein complement of a cell is subjected to a barrage of reversible or permanent modifications that control protein activity and interactions. To date, over 300 PTMs have been reported,81 including phosphorylation, glycosylation, deamidation, ubiquitination, proteolytic processing, fatty acylation, and glycosylphosphatidylinositol lipid anchor attachment. These reactions are catalyzed by enzymes that can also be regulated by PTMs. The coining of the word “proteome” has spawned terms like “phosphoproteome” or “glycome.” Inherent in these new terms is a miasma of PTMs that require systematic definition. The technologies for determination of these PTMs are in their infancy, which means throughput is slow, but significant advances are being made. The detection of PTMs using MS-based methods is challenging for several reasons. In contrast to the usual recognition of a protein, which requires the detection of only one or a few peptides, the identification of the PTM of a protein relies on the detection of the particular peptide(s) that bears the site of modification. A more complete coverage of the amino acid protein sequence can be usually achieved using individual or sequential proteolytic digestions with different enzymes. A variety of algorithms (eg, FindMod and FindPep tools, described in the Supplemental Document) have been developed that, using the peptide fingerprint of the analyzed protein, search databases for potential sites of PTMs. This technique is more reliable if it is applied following the initial identification of the protein and the search for potential PTMs is performed only using MS signals not otherwise assigned to peptide fragments. The covalent bonds between the PTMs and the peptides are of relatively low energy and therefore tend to dissociate during MS analysis, in some cases, giving rise to characteristic patterns in mass spectra that can be used for the identification of the modification.82 Algorithms have been developed that search peptide fingerprints for pairs of peaks that are potential signatures of PTMs (eg, 79 Da for phosphopeptides; Figure 7). Unfortunately, most frequently, PTMs have a low stoichiometry. A variety of methods, such as affinity purification and chemical modifications, have been developed to be used prior to the MS analysis for the enrichment and separation of proteins/peptides having the modification of interest. Figure 7 illustrates some of these in the context of protein phosphorylation.83 The variety of methodologies used for the analysis of protein phosphorylation has been thoroughly reviewed by McLachlin and Chait84 (and references within). Affinity separation followed by MS/MS analysis for the detection of phosphotyrosine-specific immonium ions has been recently successfully used for the detection of 9 phosphorylation sites of Bcr/Abl fusion oncoprotein, of which 6 were novel.85 Another elegant example is the sequential use of phosphotyrosine immunoprecipitation, methyl esterification, IMAC (Figure 7), and nanoflow reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) ES MS for the study of temporal changes in tyrosine phosphorylation following the inhibition of Bcr-Abl protein tyrosine kinase with imatinib mesylate in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells.86 The key role of tyrosine kinases in leukemogenesis determines that such approaches will be invaluable in defining downstream targets of kinases in the future. The relative and absolute quantification of drug effects on specific phosphorylation events can then be pursued using the peptide standards approach described.68,69

Overview of strategies used for the analysis of phosphorylated proteins. This overview presents only a few of the strategies currently implemented for the analysis of phosphorylated proteins. Readers are referred to reviews that cover in greater detail the variety of technologies used for the phosphoproteome analysis.84,98 The methods used prior to MS analysis are mainly concerned with the enrichment of phosphorylated proteins or peptides. (A) Immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) relies on the affinity for the phosphate group of metal ions (Fe3+ and Ga3+) that are bound to a chelating resin. Several limitations precluded the straightforward use of this method, such as binding of acidic unphosphorylated peptides that necessitate the esterification of the carboxylic acid groups and difficult elution of peptides with multiple phosphorylation sites. Another affinity purification method routinely used for the detection of sites of phosphorylation involves the use of antibodies against phosphorylated tyrosine residues (C). These have been found more efficient for the enrichment of phosphoproteins than phosphopeptides. Equivalent approaches for the enrichment of proteins or peptides containing phosphorylated serine or threonine are not yet in common use. MS-based techniques are mainly concerned with the selection, isolation, detection, and recognition of the site of modification. Precursor ion scanning has been typically used in a tandem quadrupole instrument. The first quadrupole is set to scan over the appropriate peptide m/z range, collision-induced dissociation (CID) is induced in the second quadrupole (or equivalent), and the third quadrupole is set to selectively transmit m/z 79, corresponding to

Overview of strategies used for the analysis of phosphorylated proteins. This overview presents only a few of the strategies currently implemented for the analysis of phosphorylated proteins. Readers are referred to reviews that cover in greater detail the variety of technologies used for the phosphoproteome analysis.84,98 The methods used prior to MS analysis are mainly concerned with the enrichment of phosphorylated proteins or peptides. (A) Immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) relies on the affinity for the phosphate group of metal ions (Fe3+ and Ga3+) that are bound to a chelating resin. Several limitations precluded the straightforward use of this method, such as binding of acidic unphosphorylated peptides that necessitate the esterification of the carboxylic acid groups and difficult elution of peptides with multiple phosphorylation sites. Another affinity purification method routinely used for the detection of sites of phosphorylation involves the use of antibodies against phosphorylated tyrosine residues (C). These have been found more efficient for the enrichment of phosphoproteins than phosphopeptides. Equivalent approaches for the enrichment of proteins or peptides containing phosphorylated serine or threonine are not yet in common use. MS-based techniques are mainly concerned with the selection, isolation, detection, and recognition of the site of modification. Precursor ion scanning has been typically used in a tandem quadrupole instrument. The first quadrupole is set to scan over the appropriate peptide m/z range, collision-induced dissociation (CID) is induced in the second quadrupole (or equivalent), and the third quadrupole is set to selectively transmit m/z 79, corresponding to

Proteomics experimental data archiving

The increased complexity of proteome technologies and the subsequent development of high-throughput proteome analysis resulted over the last years in an overwhelming amount of experimental data. The diversity of the data is also enhanced by the dynamics of the proteome context in which the experiments were carried out. There is a clear need to develop internationally agreed standards for archiving proteomics experimental data. Although comprehensive databases of 2-DE gels are present on the Web, such as the Expert Protein Analysis System (ExPASy), the available information is not sufficient for confident comparison of data sets. On the contrary, very few MS data sets are publicly available. The recently proposed Proteomics Experiment Data Repository (PEDRo)87 model resembles the minimum set of information about the microarray experiment (MIAME)88 model that has already been implemented for the archiving of transcriptome data. The PEDRo model takes into consideration all the various steps involved in a proteomics experiment, such as sample generation and processing, and parameters for the MS analysis and data interpretation, to capture the relevant information required for the reproduction, comparison, and archiving of any proteomics experiment.

In many respects the repertoire of experiments that can be performed in hematology has been expanded greatly by advances in MS and proteomics. This review gives an overview of some of these approaches and where they can be applied to hematology. It is likely that within 5 years their application will have transformed our knowledge of key process in normal and malignant hematopoiesis and blood cell function.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, January 15, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3295.

Supported by grants from Leukaemia Research Fund United Kingdom.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The authors are grateful to Elaine Spooncer and Wenzhu Zhang for critical reading of this manuscript.

![Figure 3. MS instrumentation used in proteomics. The fundamental principle of MS analysis involves the conversion of the subject molecules to either cations or anions in the ion source, separation according to their mass/charge (m/z) ratios in the mass analyzer, and subsequent detection. Several configurations of mass spectrometers that combine ES and MALDI with a variety of mass analyzers (linear quadrupole mass filter [Q], time-of-flight [ToF], quadrupole ion trap, and Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance [FTICR] instrument) are routinely used. (A) In MALDI, the sample is embedded in a large excess of a matrix that has a strong absorption at the laser wavelength. Following the laser irradiation of the sample surface, the matrix accumulates a large amount of energy that is thought to initiate the proton transfer between the matrix and the analyte compound to form ions. The ions observed during MALDI MS are mainly singly charged. This results in simple spectra (because the m/z ratio is what is being measured) even in the case of analysis of mixtures but can be a disadvantage for peptide sequencing, which requires the achievement of peptide fragmentation, a process that preferentially occurs with multicharged peptides. The concurrent and independent development of ToF mass analyzer and its compatibility with this ionization method resulted in the rapid development of MALDI-ToF as a routine analytical mass spectrometer.92 Other configurations, however, have also been successfully applied for the analysis of peptides and proteins, such as MALDI-ion trap,50 MALDI-QqToF52 (where q represents a quadrupole ion decomposition region), and MALDI-ToF-ToF.51 This type of ionization method is also used in SELDI-ToF MS. (B) ES is a continuous nebulization process that produces ions directly from solution and facilitates interfacing of LC with MS. A sample is passed with flow rates of 1 to 10 μL/min through a capillary held at high potential relative to ground and counter electrode. The strong electric field obtained induces charge accumulation at the liquid surface situated at the end of the capillary and leads to the formation of a mist of highly charged droplets. The ES process results in the formation of multiply charged ions. This is one of the principal advantages of this method because it allows the analysis of ions from high-molecular-mass molecules, such as proteins and peptides, using mass spectrometers of limited m/z ratio range. (C) The quadrupole analyzer is frequently termed a mass filter because it transmits only ions within a narrow m/z range. The analyzer uses the stability of the trajectory to separate these ions according to their m/z ratio. The stability of the oscillating trajectories of the ions is based on the joint application of direct current and radio-frequency voltages on 4 parallel cylindrical metal rods. (D) Unlike the scanning devices such as quadrupoles, ToF analyzers separate ions temporally rather than spatially. The ions are rapidly accelerated into a “field-free” drift region also called a “flight tube,” and their separation is achieved by measuring the difference in transit time from the ion source to the detector. The reflectron, which consists of a series of rings or grids that act as an ion mirror, compensates for the initial kinetic energy distributions of ions. (E) The ion trap analyzer captures the ions, which collide with the helium “bath” gas and start to oscillate in a predicted motion. Ion trap can be used as a “tandem-in-time” instrument as selection, fragmentation, and analysis of ions take place in the same space. Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer (FTICR; not illustrated) is also a trapping device, in this case by using strong magnetic fields, and offers great opportunities for investigating protein interactions and PTMs, with high sensitivity, mass accuracy, and resolution.93](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/103/10/10.1182_blood-2003-09-3295/6/m_zh80100460910003.jpeg?Expires=1770241443&Signature=4AdT-t48MEn2Vy9n6yxHyxLq8uCgxVBlFcR1w7cnreqLNCX9d8yRdrc0bxOgOxIAV09loBB0eVyb5o3ffrcKydZT6DQr9qxV66FPv~c6xyBpj4LozYD~Hs~~2y8QnNA5siLj-culwMlMASV7Zua4bQSIrPFcJaCC7hFVgHAiYZstxhS7xJnVFsGs76A0amWhS4RS9Rmwhf5c0EJ17xSA33QMkqpBN0d71vybldqkp9dpTKk9bu9HHw2dJkodghISkJvw3YLoPBpNhvZMHId1qG2~MHQZVwIlcCDZu6WgDf4X8su1xPqws7A9KlhAxwFLqJ3FI-PJCAqwBPiE~E~vow__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. Sequencing of peptides using MS/MS. Peptide fragmentation by collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) during MS/MS48 allows the recognition of complete or partial peptide sequence. Following collisional activation, the peptides undergo fragmentation along the backbone or in their side chains giving rise to product ions that can be attributed to the amino acid sequence. The nomenclature for classifying these ions allows the labeling of all the various fragment ions. The 3 possible cleavage points of the peptide backbone are called an,bn, and cn when the charge is retained at the N-terminal fragment of the peptide, and xm,ym, and zm when the charge is retained by the C-terminal fragment. The subscripts n and m indicate which amide bond is cleaved counting from the N- and C-terminus, respectively, and thus also the number of amino acid residues contained by the fragment ion. Immonium ions and internal fragments are usually labeled with the letter codes of the amino acids (not indicated in this figure). Product ions derived from fragmentation at the side chain of the peptide (labeled d, v, and w) are not discussed here. Panel A illustrates the ES Q-ToF product ion spectrum of [M+2H]2+ at 768 m/z, corresponding to fibrinogen αA from rat hepatocytes, following digestion with trypsin, where [M+2H]2+ denotes the doubly charged precursor ion selected for fragmentation. An almost complete series of b and y ions was obtained in this analysis resulting in a facile identification of the peptide sequence. Panel B illustrates the application of MS/MS analysis for the search for sites of phosphorylation. The product ion spectrum, recorded in positive mode, was obtained from the 1-dimensional liquid chromatography-tandem electrospray mass spectrometry analysis (LC-MS/MS) of a phosphorylated peptide. The signals between 1200 and 2000 m/z are magnified by a factor of 2.5. The sites of phosphorylation are searched by scanning for loss of phosphate or for characteristic immonium ions (Figure 7). [M+2H]2+ denotes the doubly charged precursor ion selected for fragmentation, and the [M+2H]2+-H3PO4 denotes the characteristic loss of the phosphate moiety from the precursor ion.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/103/10/10.1182_blood-2003-09-3295/6/m_zh80100460910005.jpeg?Expires=1770241443&Signature=JZbhLr--7~3TDEcxxKHGLOI7ymkCIsuHYIS1gKW4y8aTgMasCjPp0podP1DuuVlnmR5RTlPC6j8Zwjrl4cHw553GPI8dZ01SJwuiK-EBr93fSjesOaz0yzRHNW2d7XKnsIADwevhgoxGIngR9RJZoViO5vSqDJr~DETH-Wq385NdS7kCLrU38TXpaZxM9okESbU5CqFAwmDOYVPaRtwULlPjjr2rzGJEYMnSq9eN5iaUJP~j-PTUBc4fBv7AMZceWfVIip3qONuHLUeW2Zo805dCf9ukGA81eFwrhiZXNRrVWtnmu9elaYKQMaAkibVkBFNwcrHB2YNZrmJUpvR84w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)