Sperm protein 17 (Sp17) is a highly conserved mammalian protein initially isolated from rabbit epididymal sperm membranes and testis membrane pellets.1 Subsequently, Sp17 has been detected in mouse, monkey, baboon, macaque, and human (HSp17) testis and spermatozoa. Recently, using a pair of sequence-specific primers, the presence of HSp17 mRNA has been shown in 2 myeloma cell lines, in 17% of patients with multiple myeloma, and in the primary tumor cells from 70% of patients with ovarian carcinoma.2-5 Chiriva-Internati et al have shown that HSp17 contains functional cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes.3 These results brought the conclusion that HSp17 is a cancer-testis (CT) antigen in multiple myeloma and ovarian carcinoma and suggest its suitability as a target for immunotherapy of these 2 neoplastic diseases.

CT antigens constitute a group of proteins that are expressed in histologically different types of malignant human tumors and are restricted in normal tissues to germ cells of the testis, with occasional expression in female reproductive organs. Their immunogenicity and tissue localization make them valid candidates for developing specific active immunotherapy procedures. Chiriva-Internati et al stated that HSp17 could be an ideal target for the following 2 reasons.3 First, HSp17 seems to have a very restricted distribution in healthy tissues, as shown by Northern blot and reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of RNA from a panel of normal tissues;2 therefore, minimal nonspecific toxicities can be expected from an HSp17-based tumor vaccine.3 Second, in vivo clinical safety of an HSp17-based vaccine could be deduced from the apparent lack of illness in men who develop anti-HSp17 antibodies after undergoing vasectomy.3

In clinical materials, the expression of CT antigens has mostly been studied at the level of gene expression by RT-PCR. The information provided by this approach, however, is limited; it does not allow the quantification of cancer cells, which are positive for CT antigens.6 On the contrary, the availability of specific antibodies enables the recognition of the antigen within examined tissues, highlighting not only the quantity but also the type of cells immunopositive for that antigen.

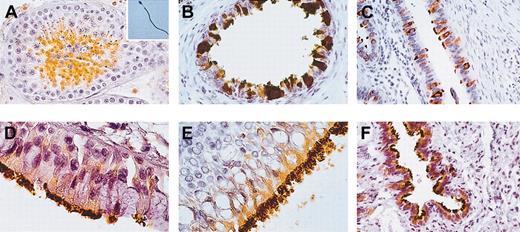

Using self-produced mouse anti-HSp17 antibodies,7 the expression pattern of this antigen in pathology-free samples of human testis and ejaculated spermatozoa was investigated. A large number of seminiferous tubules were highly positive for HSp17 as well as the flagella of the spermatozoa identified in the lumen of these tubules and in ejaculated spermatozoa (Figure 1A).

Immunohistochemistry for HSp17 in human testis, ejaculated spermatozoa, and paradigmatic human ciliated epithelial cells. (A) Histologic section of healthy testis. HSp17 was found in spermatocytes and abundantly in spermatids, while spermatogonia and Sertoli cells were found to be immunonegative. Hsp17 was strongly found throughout the principal piece of the flagellum in a large amount of fertile ejaculated spermatozoa (inset). (B) Histologic section of ductuli efferenti of the male germinal tract, (C) tubes of the female genital tract, (D) trachea, (E) larynx, and (F) lung. (B-F) HSp17 was expressed in the cytoplasm of lining ciliated epithelial cells and their cilia. Original magnification × 400 for panels A-C and F; × 1000 for panels D, E, and inset. Indirect immunoperoxidase staining was used.

Immunohistochemistry for HSp17 in human testis, ejaculated spermatozoa, and paradigmatic human ciliated epithelial cells. (A) Histologic section of healthy testis. HSp17 was found in spermatocytes and abundantly in spermatids, while spermatogonia and Sertoli cells were found to be immunonegative. Hsp17 was strongly found throughout the principal piece of the flagellum in a large amount of fertile ejaculated spermatozoa (inset). (B) Histologic section of ductuli efferenti of the male germinal tract, (C) tubes of the female genital tract, (D) trachea, (E) larynx, and (F) lung. (B-F) HSp17 was expressed in the cytoplasm of lining ciliated epithelial cells and their cilia. Original magnification × 400 for panels A-C and F; × 1000 for panels D, E, and inset. Indirect immunoperoxidase staining was used.

Since the flagella of spermatozoa are similar to cilia in their structure,8 and since a common origin of cilia and flagella in eukaryotes has been proposed, we then investigated whether HSp17 was detectable in human ciliated epithelia.

We found that HSp17 was strongly detected in ciliated epithelia of the respiratory airways and both the male and female reproductive systems (Figure 1B-F).

These data extend recent reports in which a proteomic analysis of human airway cilia revealed the expression of HSp17,9 and in which an RT-PCR analysis from a panel of human complementary DNAs10 showed HSp17 transcripts in all human tissues examined, including lung and other organs that contain different amounts of ciliated cells.

Since cilia have been adapted as versatile tools for many biologic processes, such as left-right axis pattern formation, cerebrospinal fluid flow, sensory reception, mucociliary clearance, and renal physiology,8 it is reasonable to hypothesize that HSp17 may be involved in many complex functions other than sperm-egg interaction,10 as originally thought.

These new findings seriously question the usefulness of HSp17 in immunotherapy protocols and necessitate further research to evaluate suitability of HSp17 as a human therapeutic antigen; therefore, its use for clinical purposes at this time is very premature.

Supported by grants from the Women's Health Research Institute, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Amarillo, TX; and the Foundation “Michele Rodriguez,” Milan, Italy.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal