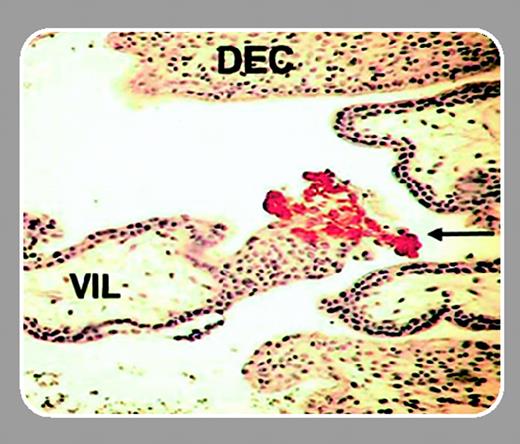

Mammalian pregnancy represents an immunologic paradigm. Not only does the maternal immune system recognize the fetoplacental unit but it creates an environment in which the developing fetus will flourish. A subpopulation of natural killer (NK) cells is of particular interest. These cells accumulate and proliferate in decidualizing human uteri anticipating successful implantation of the embryo. As part of the innate immune system, uterine NK cells are well-qualified to seek out and destroy foreign tissue, such as fetal trophoblast cells, that form the placenta, but in pregnant uteri they appear to lack cytotoxicity. Rather, a key role hypothesized for uterine NK cells is to participate in physiologic changes to maternal arteries through cytokine secretion. The changes optimize blood flow into the feto-placental unit and presumably require positional information from invasive fetal trophoblast cells. In primate uteri, NK cells appear in 2 waves: the first wave is in the postovulatory period of each menstrual cycle when uterine stromal cells undergo transformation to decidua, and the second wave is in response to implantation and pregnancy. Terminal differentiation and proliferation of NK cells occur in the uterus. Although decidua-associated NK cells have been reported in many species, the mechanisms explaining their recruitment are mysterious.FIG1

Previously, subsets of peripheral blood NK cells (CD56bright, CD56dim, and NK-T) were shown to express distinct patterns of chemokine receptors and responsiveness. Hanna and colleagues (page 1569), in a series of exacting experiments, build on this approach to explore the role of uterine-secreted chemokines in NK-cell recruitment to pregnant uterus. From analyses of mRNA, protein, and the function of chemokine receptors of uterine CD56+CD16– NK cells and CD16– and CD16+ peripheral blood NK cells, 2 pivotal insights were revealed. Uterine NK cells, shown to express unusually high levels of CXCR4 and blood-equivalent levels of CXCR3, are recruited within implantation sites by a specific subset of fetal placental cells called extravillous trophoblasts. These trophoblasts, which reside in the decidua and replace maternal endothelium in the major decidual arteries, are the only trophoblast subsets expressing CXCL12 (stromal cell–derived factor-1α/β [SDF1α/β]), the CXCR4 ligand. The second insight is that decidual expression of CXCL12, CXCL9, and CXCL10 is much greater than placental expression. These data explain how CD16– NK cells, or even earlier lymphoid lineage progenitor or stem cells, through high-level coexpression of CXCR4 and CXCR3, are recruited to decidualizing uteri during menstrual cycles when trophoblast cells are absent.

Interleukin 15 (IL-15), a cytokine essential for NK-cell differentiation and showing regulated expression in early decidua and uterine arterial endothelium, gave NK cells in blood lymphocyte cultures a uterine NK-cell chemokine receptor expression profile. This, plus the finding that transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), a decidually expressed cytokine involved in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, up-regulates NK-cell CXCR4, strengthens the hypothesis that human uterine NK cells act in concert with extravillous trophoblasts in the placental bed region of the uterus and contribute to the cardiovascular adaptations of early pregnancy.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal